30 May Wildlife Art in the West

EVERY YEAR, HUNTERS CARRY DUCK STAMPS IN THEIR CAMOUFLAGED JACKETS. Families have cheap posters of grizzly bears and elk on the walls of their cabins in the woods. Sports teams have adopted certain species as their enduring mascots. And multi-national companies spend millions marketing animals as part of corporate branding and PR campaigns, promoting themselves as sound stewards of the Earth to win the hearts of consumers.

These are the superficial clichés of what wildlife art is. The images are all around us, ubiquitously. And it is against this backdrop that artists engaged in the genre have fought a never-ending battle for self-respect.

Yet, by any objective measure, wildlife art — long treated with derision by some in the American fine art establishment — may finally be coming of age with critical recognition.

Fueled by huge attendance at museum exhibitions; soaring prices fetched for wildlife paintings and sculpture sold at auction; widening public concern for environmental issues; revived interest in Realism; and centers like the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls opening a permanent installation devoted to artistic celebrations of the bison, art historians say that subject matter once written off as prosaic is assuming greater contemporary relevance in the 21st century.

Whether used as fodder for experimental expression by the likes of controversial Englishman Damien Hirst, who has sold individual works featuring dead animals for staggering eight-figure sums, or treasured as investments, simple decoration on the wall, or touchstones of history, the symbolism of wildlife has never been more potent or poignant, says James McNutt, president of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming.

Today, nothing proclaims the rising stature of wildlife art more loudly perhaps than the National Museum of Wildlife Art being declared, in 2008, as the official fine art institution for the genre in the country and, as notably, the only museum of its kind on the globe.

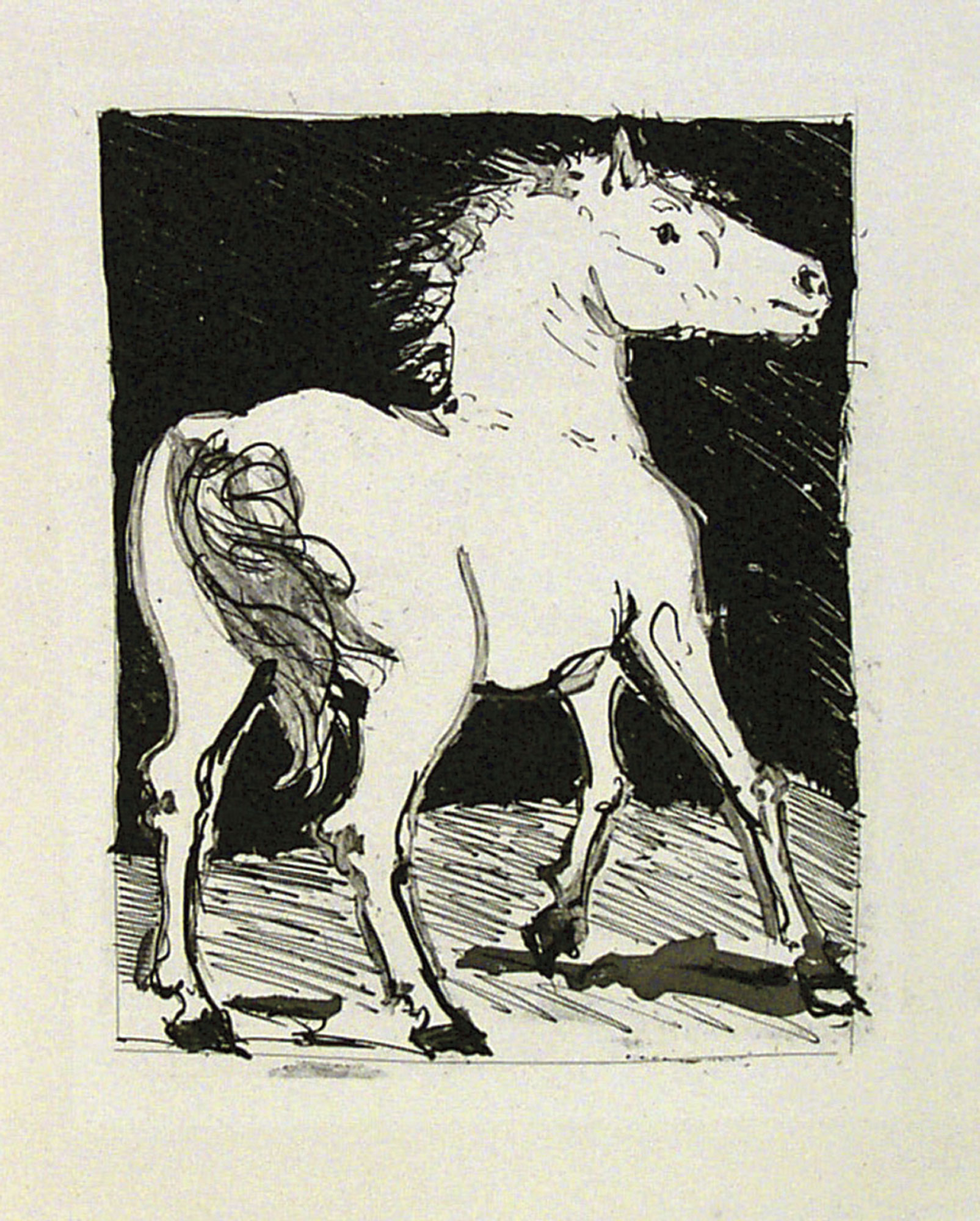

That it is located in the heart of the West is not accidental; that it holds a plethora of classical Western artists, including Carl Rungius, Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, whose works are displayed alongside animal pieces by Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, Edwin Landseer, Bruno Liljefors, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Edward Kemeys, Anna Hyatt Huntington and Frank Benson breaks the stereotype of its affiliation with kitsch.

Designated by act of Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush, the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s accomplishment echoes of a related and momentous gesture taken 136 years earlier just up the road — the setting aside of Yellowstone as the first national park in the world, spawning the birth of the global conservation movement that continues to this day.

Yellowstone’s creation, too, had an artistic connection to nature at its core, for the most persuasive evidence cited to preserve its steamy wonderland were grand landscape paintings — some of them containing wildlife as reference points — that were displayed before lawmakers in the nation’s capital. Unveiling wildlife art to make a case for politicians to think beyond their own tenure, in perpetuity, was repeated time and again, with Yosemite and the protection of numerous other preserves.

Animal imagery represents its own rich vein within Western art, with motifs of birds, mammals, fish and sporting scenes proving to be no less cherished in collectability than portrayals of cowboys, Indians, pure landscapes and bronze bucking broncos. Select a major fine art mecca — the L.A. County Art Museum, the Heard in Phoenix, the Gilcrease in Tulsa, the Denver Art Museum, the Joslyn in Omaha, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Corcoran in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan in New York City or grand Eastern parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted — there, animals inhabit a venerated space in the human mind.

At the National Gallery of Art between the White House and Capitol Hill on the National Mall, you can find a coveted painting by Winslow Homer, Right and Left, one of the last pieces to leave his easel in 1909, the year before his death, portraying two ducks bagged in a double over the water. Filled with allegory and sophisticated elements of composition, its subject matter cannot be denied.

Homer’s elevation of wildlife art defies, however, its more humble, utilitarian roots. The first expressions of the animal form and profile, of course, reach back to a time when art was inseparable from human spirituality, sustenance and survival.

Even with carbon dating, historians cannot give us the name of artisans who rendered the first aboriginal paintings on rawhide and rock faces in North America because they were not signed; nor were the amulets and totem poles, portraying beasts carved as spiritual talismans.

One of the first interpretations of Western wildlife put on to paper was a crude portrayal of a bison in Mexico. In 1552, Spaniard Francisco Lopez de Gomara published a basic depiction of Bison bison in his book Historia de las Indias. The engraved image came decades after sightings of the woolly bovines were made by Hernando Cortez and his Conquistadors — a century before English pilgrims spied Plymouth Rock.

Subsequently, each successive wave of exploration launched into the West from the East carried with it a trained or untrained artiste de camp, giving American wildlife art its own distinctive legacy.

At the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, there is an epochal painting that conveys the magical allure of the West. It is not a Western scene, however, but a self portrait of master painter Charles Wilson Peale, portrayed pulling open a curtain and inviting the viewer to tour a backroom filled with live animals and artifacts collected by Lewis and Clark, Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike and Major Stephen Long on their research expeditions into what Thomas Jefferson dubbed terra incognita.

The specimen gathering and illustrations rendered by Peale, his son, Titian, and artists such as Samuel Seymour ignited a flurry of national appreciation for the role of artists as documentarians. Indeed, it established the groundwork for artists conveying the West as both a real and mythological realm, a tableau for the likes of George Catlin, Karl Bodmer, John James and John Woodhouse Audubon, Arthur Tait (of Currier & Ives fame) Paul Kane, Louis Agassiz Fuertes and photographers from William Henry Jackson to Edward Curtis, Ansel Adams and countless successors. Some chronicled species that now are extinct.

The annihilation of 30 million bison caused the world to pause and take notice in works by John Mix Stanley, Alfred Jacob Miller and Albert Bierstadt. Bierstadt’s monumental oil Last of the Buffalo at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, is considered a masterpiece for the ages.

With the West tamed and depopulated of its game, wildlife artists were summoned again, this time by George Bird Grinnell and Theodore Roosevelt, among others in the cause of enlisting hunters and anglers to promote conservation.

Wildlife art was not about making mere pretty pictures but it rippled as a social commentary on the limits of conquest and Manifest Destiny. It became fertile ground for N.C. Wyeth, William R. Leigh, Maynard Dixon, Frank Tenney Johnson and artists from the Taos School. Among Native American artisans, the tradition continues, unbroken, in pottery, textiles, rock art and on organic surfaces.

As a phenomenon of persistence engrained in the psyche of the West, wildlife has, and remains a centrifugal force that sets the region apart with its own identity.

In the early 1990s, I attended an unprecedented gathering of “wildlife artists” sponsored by the Society of Animal Artists and the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History in Jamestown, New York. Sharing their passion were many of the finest living wildlife painters and sculptors of the 20th century.

“[Wildlife] art has been scored by some critics as being too conservatively academic, as ignoring abstraction, geometrics, subconscious comment and other manifestations of contemporary art,” noted the late Roger Tory Peterson, who pioneered the modern avian field guide and filled them with paintings he made of birds. “Actually, those who paint or draw wildlife in their representational manner are making a statement about their world — the natural world — that is every bit as valid as that of the avant-garde interpreters of the synthetic city scene.”

Peterson added: “Wildlife artists have finally been liberated and are more generally accepted into the mainstream of the art world, and are among the most effective messengers of the conservation and environmental movements.”

That was more than 15 years ago.

The Society of Animal Artists, based in New York City and the oldest association of wildlife artists in the world, is so certain of the West’s role in elevating its genre that in 2010 it will hold its 50th anniversary in San Diego.

In American Wildlife Art, the new encyclopedic tome by David J. Wagner, Canadian painter Robert Bateman says wildlife art has been in ascent for 30 years. Indeed, despite the recession, works by deceased and living wildlife artists enjoy a strong following at such prominent venues as the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Center’s Prix de West Invitational (every June) in Oklahoma City; the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction in Reno (in July); the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Western Visions Miniature Show (September); the Jackson Hole Art Auction (September); the Buffalo Bill Art Show in Cody (the last week of September); the Santa Fe Art Auction (November); the Coors Art Show in Denver (January); the Autry Center’s annual Masters of the American West Show (February) in Los Angeles; and the C.M. Russell Museum Art Auction (every March).

“I wouldn’t describe what is happening today as a renaissance of wildlife art,” McNutt, from the National Museum in Jackson Hole, says. “What has evolved to be known collectively as ‘wildlife art’ has been affected by the movements that all of the other artists who ever lived were a part of, too. Wildlife art invites us to look back at the West with a deeper appreciation of those who carried forth a message. But another element involves encouraging artist expression that helps us make better sense of the present. Wildlife art is about the time in which we live.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: In the spring of 2009, Western Art & Architecture unveiled an online sister magazine, Wildlife Art Journal, that is devoted to connoisseurship with animal motifs in painting, sculpture and art of the natural world.

Todd Wilkinson has been writing about the art of nature and wildlife for more than two decades. A journalist based in Bozeman, Montana, he is working on a book about media mogul turned bison baron and environmental humanitarian Ted Turner.

Yellowstone’s creation, too, had an artistic connection to nature at its core, for the most persuasive evidence cited to preserve its steamy wonderland were grand landscape paintings — some of them containing wildlife as reference points — that were displayed before lawmakers in the nation’s capital. Unveiling wildlife art to make a case for politicians to think beyond their own tenure, in perpetuity, was repeated time and again, with Yosemite and the protection of numerous other preserves.

Animal imagery represents its own rich vein within Western art, with motifs of birds, mammals, fish and sporting scenes proving to be no less cherished in collectability than portrayals of cowboys, Indians, pure landscapes and bronze bucking broncos. Select a major fine art mecca — the L.A. County Art Museum, the Heard in Phoenix, the Gilcrease in Tulsa, the Denver Art Museum, the Joslyn in Omaha, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Corcoran in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan in New York City or grand Eastern parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted — there, animals inhabit a venerated space in the human mind.

At the National Gallery of Art between the White House and Capitol Hill on the National Mall, you can find a coveted painting by Winslow Homer, Right and Left, one of the last pieces to leave his easel in 1909, the year before his death, portraying two ducks bagged in a double over the water. Filled with allegory and sophisticated elements of composition, its subject matter cannot be denied.

Homer’s elevation of wildlife art defies, however, its more humble, utilitarian roots. The first expressions of the animal form and profile, of course, reach back to a time when art was inseparable from human spirituality, sustenance and survival.

Even with carbon dating, historians cannot give us the name of artisans who rendered the first aboriginal paintings on rawhide and rock faces in North America because they were not signed; nor were the amulets and totem poles, portraying beasts carved as spiritual talismans.

One of the first interpretations of Western wildlife put on to paper was a crude portrayal of a bison in Mexico. In 1552, Spaniard Francisco Lopez de Gomara published a basic depiction of Bison bison in his book Historia de las Indias. The engraved image came decades after sightings of the woolly bovines were made by Hernando Cortez and his Conquistadors — a century before English pilgrims spied Plymouth Rock.

Subsequently, each successive wave of exploration launched into the West from the East carried with it a trained or untrained artiste de camp, giving American wildlife art its own distinctive legacy.

At the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, there is an epochal painting that conveys the magical allure of the West. It is not a Western scene, however, but a self portrait of master painter Charles Wilson Peale, portrayed pulling open a curtain and inviting the viewer to tour a backroom filled with live animals and artifacts collected by Lewis and Clark, Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike and Major Stephen Long on their research expeditions into what Thomas Jefferson dubbed terra incognita.

- Pablo Picasso (Spain, 1881 – 1973) | “Le Cheval (The Horse), 1942” | Ink on Paper | 15 x 11 1/2 inches | From “Picasso; Eaux-fortes Originales pour des textes de Buffon” Edited by Martin Fabiani; 1942 | Promised Gift of Dick and Gina Heise, National Museum of Wildlife Art © 2009 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

No Comments