29 Dec Natural Affinities

THE FOLLOWING EXCERPT IS FROM Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities, a stunning and insightful book recently published by Little Brown. The book, and a traveling exhibition of the same name, present — for the first time — the work of two of America’s best-known artists, and portrays the complex and often shifting relationship the artists had with one another over nearly six decades. In the end, the only unfailing bond the two shared was a particular passion for the New Mexican landscape.

By the end of their lives in the 1980s, Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams had settled, more or less comfortably, into their now-familiar roles as beloved eminences, artists whom every citizen could revere. As fellow survivors of the battles over American art in the first half of the 20th century and living proof of its ultimate recognition, they deserved to bask in their country’s regard and feel a glow of kinship. Both gave every appearance of a harmonic friendship to go along with the national honors and museum retrospectives. …

They knew each other from 1929 until Adams’ death in 1985, and one of the emotional ties binding them over the decades was an attraction to the Southwest. Although their love for the place developed under separate circumstances, New Mexico was where they met and where each produced significant bodies of work based on their responses to the area’s distinct landscape, atmosphere and history. Their enraptured images of its adobe architecture, mountains, forests, desert vistas and weather had become by the time of their deaths so persuasive that other painters and photographers working here found their work compared, often invidiously, to what the pair had accomplished. This is no less true today.

Any 56-year relationship, however, will also produce its share of bumps along the way. Despite their mutual longevity, veneration of America’s diverse natural heritage, and the towering status of their images in the canon of American modernism as well as in popular culture, they had incongruous temperaments, a discrepancy that spilled over into their art and their reactions to public acclaim. …

The impulses that carried them toward New Mexico were also quite different. In O’Keeffe’s case, it was her wish to replenish the well of inspiration for her work, seemingly exhausted during her years on the East Coast married to Alfred Stieglitz with their constant social and family obligations. For Adams, at least on his first visits during the late 1920s, it was the chance to venture beyond California and to meet writers and artists from the East. O’Keeffe had taught and done important work in the Southwest during the second decade of the 1900s. By returning there almost every year from 1929 until her permanent move in 1949, she was seeking to reconnect with the western landscape while putting distance between herself and the art world of Manhattan; Adams, on the other hand, was delighted for the first time to encounter, in Taos, avant-garde New Yorkers such as Paul Strand, whom he met during a crucial visit there in 1930.

O’Keeffe received more than a dozen mentions in the Adams autobiography, posthumously published in 1985. But the references are in places tinged with ambiguity. Adams calls her “a great painter” while also stating that her art at times baffled him: “In the presence of O’Keeffe’s paintings, I cannot claim to fully understand them,” he admitted. His most unreserved superlative refers to her person: “She has the most impressive physical presence of anyone I have ever met.” When he writes that “her genius will always be in flower, no matter what age or events come upon her,” this is just after he recalls her teasing him on his 82nd birthday that “I shall always upstage you by 15 years!”

Tension as well as devotion and esteem characterized the O’Keeffe-Adams relationship. There was no question who was dominant. “The Southwest is O’Keeffe’s land,” he wrote in his 1983 book, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs. “No one else has extracted from it such style and color, or has revealed the essential forms so beautifully as she has in her paintings.” He was always her junior in many respects, and she did not let him forget what he owed to Stieglitz and to Strand, both of whom had adored her. Adams, in turn, gives her second billing in the “Stieglitz and O’Keeffe” chapter of his life story, even though he actually knew her several years before he met Stieglitz, and for decades after.

As in so many matters concerning American art in the 20th century, the story of complicated affiliation between O’Keeffe and Adams goes back to the artist, inventor, impresario, troublemaker, critic and sage who helped launch both Adams and O’Keeffe in their triumphant careers. More than New Mexico or the lofty status they shared in old age, it was Stieglitz who brought them together as friends when he was alive and kept them together long after his death. …

O’Keeffe had glimpsed New Mexico a decade earlier than Adams. While on vacation in 1917 from her teaching job in Texas, she and her sister, Claudia, were forced, due to tracks washed out by bad weather, to chart a train route to and from Colorado that led them through Santa Fe. Georgia was instantly bewitched. “I loved it immediately,” she later recalled. “From then on I was always on my way back.” The blankness of the land overwhelmed her — “the nothingness is several sizes larger than in Texas,” she wrote to Paul Strand — and stayed with her long after she had gone back East. …

In the summer of 1927, 25-year-old Ansel Adams made his first visit to the Southwest, a place that eventually came to rank second in soul nourishment and importance for his photographic life after Yosemite Valley and the High Sierra. The trip was exploratory. The photographer had never been outside California and was eager to assess the wider country’s picture prospects.

Looking back on his younger self in his autobiography, he fondly recalled the adventure. He had chauffeured his friend and earliest patron, Albert Bender, along with Bender’s friend Bertha Pope, a wealthy woman from the Berkeley area whose accumulated purchases of Indian rugs and pots threatened by the end to capsize their Buick touring car.

The ride from San Francisco in the pre-air-conditioned, pre-interstate era proved to be rough: “Twelve hundred long miles, mostly on wash-board roads,” in Adams’ words, almost 300 miles longer than the current shortest route. But hardship was rewarded by dazzlement once they reached Santa Fe.

In typical fashion, Adams’ keenest memory about his first view of the second-oldest city in the United States (established in 1609) pertained to weather. As he motored into town late in the day, they were greeted by a dust storm that, he claimed, ruined his “hopes for a land that had promised many new photographs.” Just as typically, his low spirits lifted as soon as conditions for picture-making improved. “The next morning all was diamond bright and clear,” he went on, “and I fell quickly under the spell of the astonishing New Mexican light.” …

Many more visits followed over his lifetime. Although he never again devoted an entire book to images of the state, Photographs of the Southwest, published in 1976, collects many of them. He made a number of his most renowned landscapes in New Mexico: Ghost Ranch Hills, Chama Valley, 1937; Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941; White House Ruin, Canyon de Chelly, 1942; Aspens, Northern New Mexico, 1958; and Thunderstorm Over the Great Plains, near Cimarron, 1961.

If Adams saw any of O’Keeffe’s sketches or canvases when they were in Taos, he didn’t say. Contemporary painting often bewildered him. Diego Rivera’s frescoes were “grand,” but Picasso’s analytic cubism and the theories of art by Dow and Kandinsky, which excited Stieglitz and O’Keeffe, did not consume his mind. He was markedly less traveled and formally educated than O’Keeffe. He did not see New York until 1933 or visit Europe until 1974, at the age of 72. His formal education ended with today’s equivalent of the eighth grade. Instead, Adams belongs in the hallowed American tradition of brilliant autodidacts. …

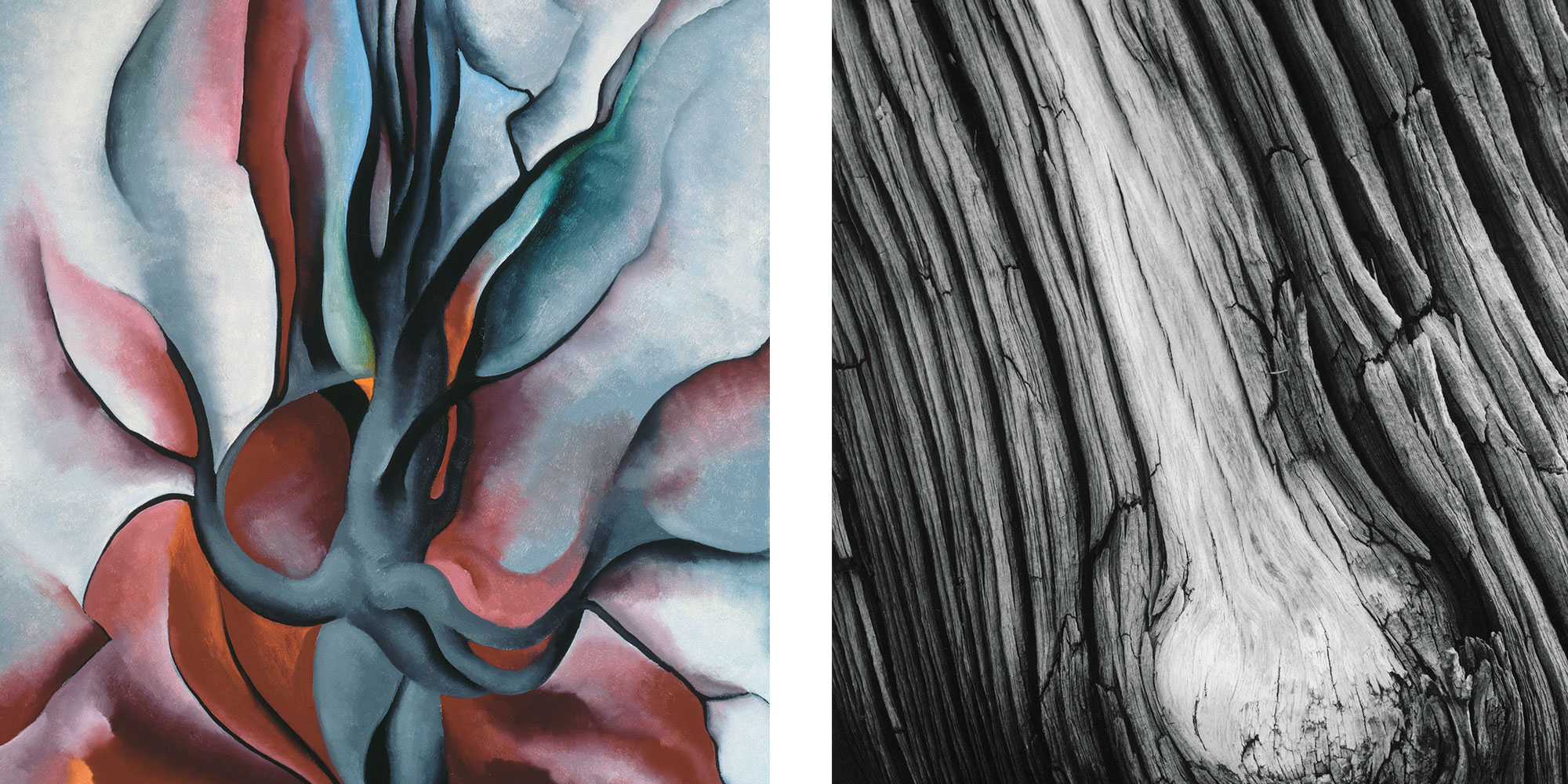

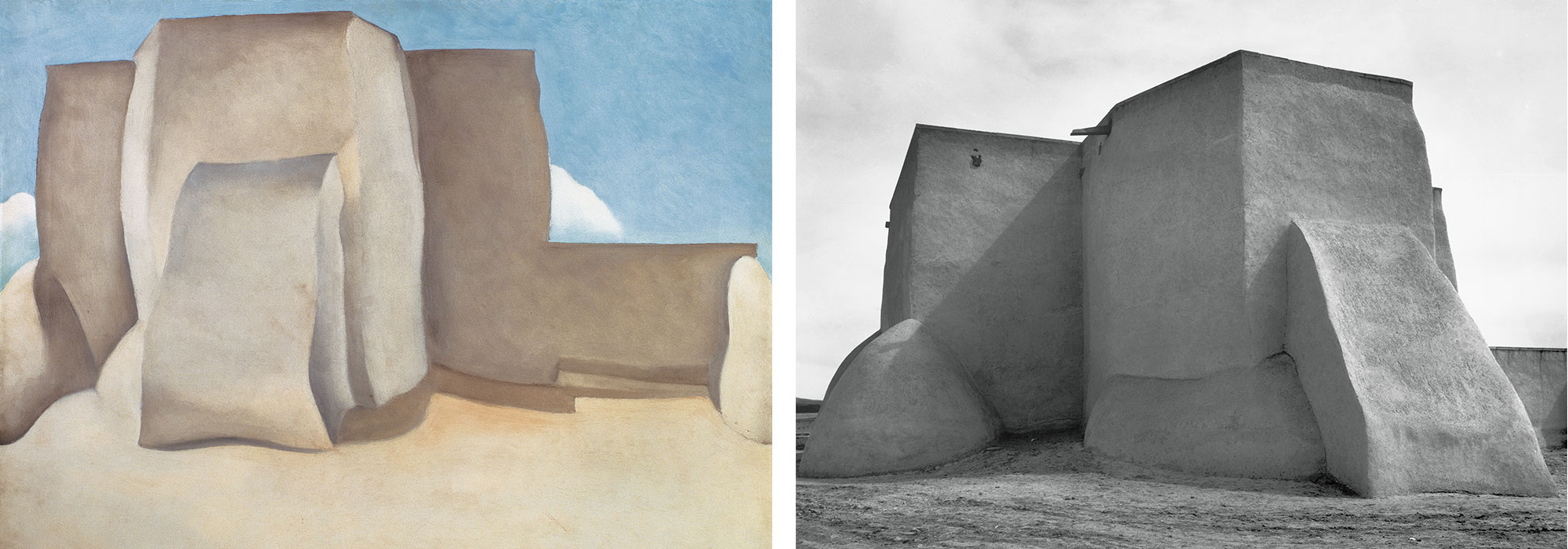

As O’Keeffe and Adams grew older, the two must have realized how much they had in common, in the people they had known and the pictures they had made. Apart from shared New Mexico motifs such as Saint Francis Church in Ranchos de Taos, Adams’ photographs in the Sierra Nevada book — Grass and Burned Stump; The Pass, with its snow-patched saddle and scree in the foreground and a swooping ring of rock behind; Rock and Water; and Lake Near Muir Pass resemble in feeling and composition O’Keeffe’s landscapes.

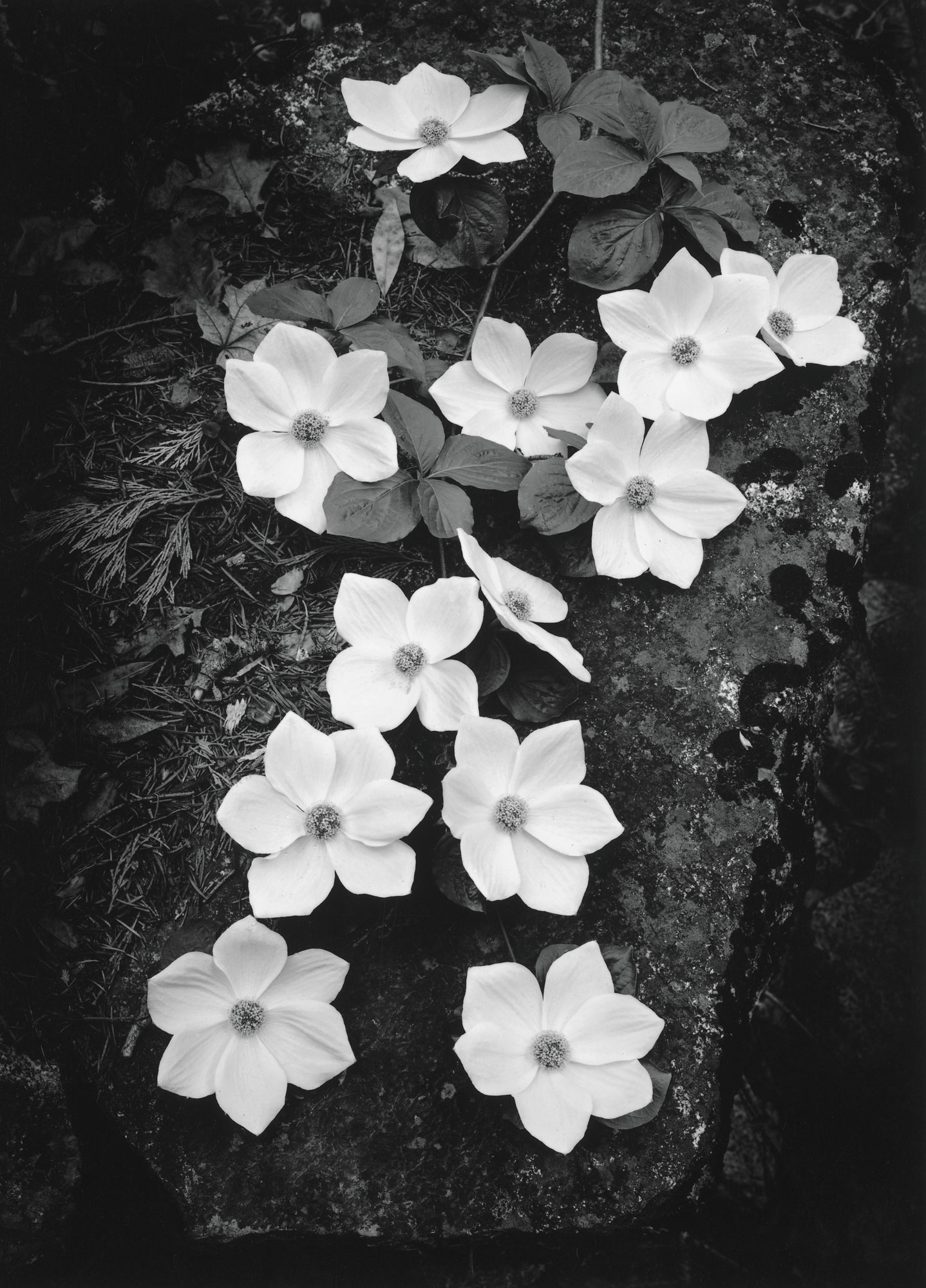

It might be said, though, that an Adams close-up — of, say, flowers in a fissure of rock — is where O’Keeffe’s eye gets interested, boring into the heart of the plant. She isn’t painting the stripes on the lily, or even “liliness,” but rather is seeking to capture that instant of transformation when seeds shatter into bloom, color fuses with form and matter becomes energy. Adams seems just as awestruck by this process in certain photographs, but the phenomenal world is also delineated. Many pictures show an ecological sensitivity to plants and soil, not just the framer’s eye for solids and voids. The vital importance of water for a single object or a patch of land can often be inferred even when not footnoted in a vapor of cloud or distant flume.

Richard B. Woodward is an arts critic based in New York. His writings have appeared in several monographs and catalogs as well as in The Atlantic Monthly, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. He contributes regularly to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Guardian.

- Left: Georgia O’Keeffe, “Ranchos Church No.1”, 1929, oil on canvas, 18 3/4 x 24 inches, CR 664, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. | Right: Ansel Adams, “Saint Francis Church, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico”, c. 1929, gelatin silver print, 13 5/16 x 17 9/16 inches, The Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. ©2008 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

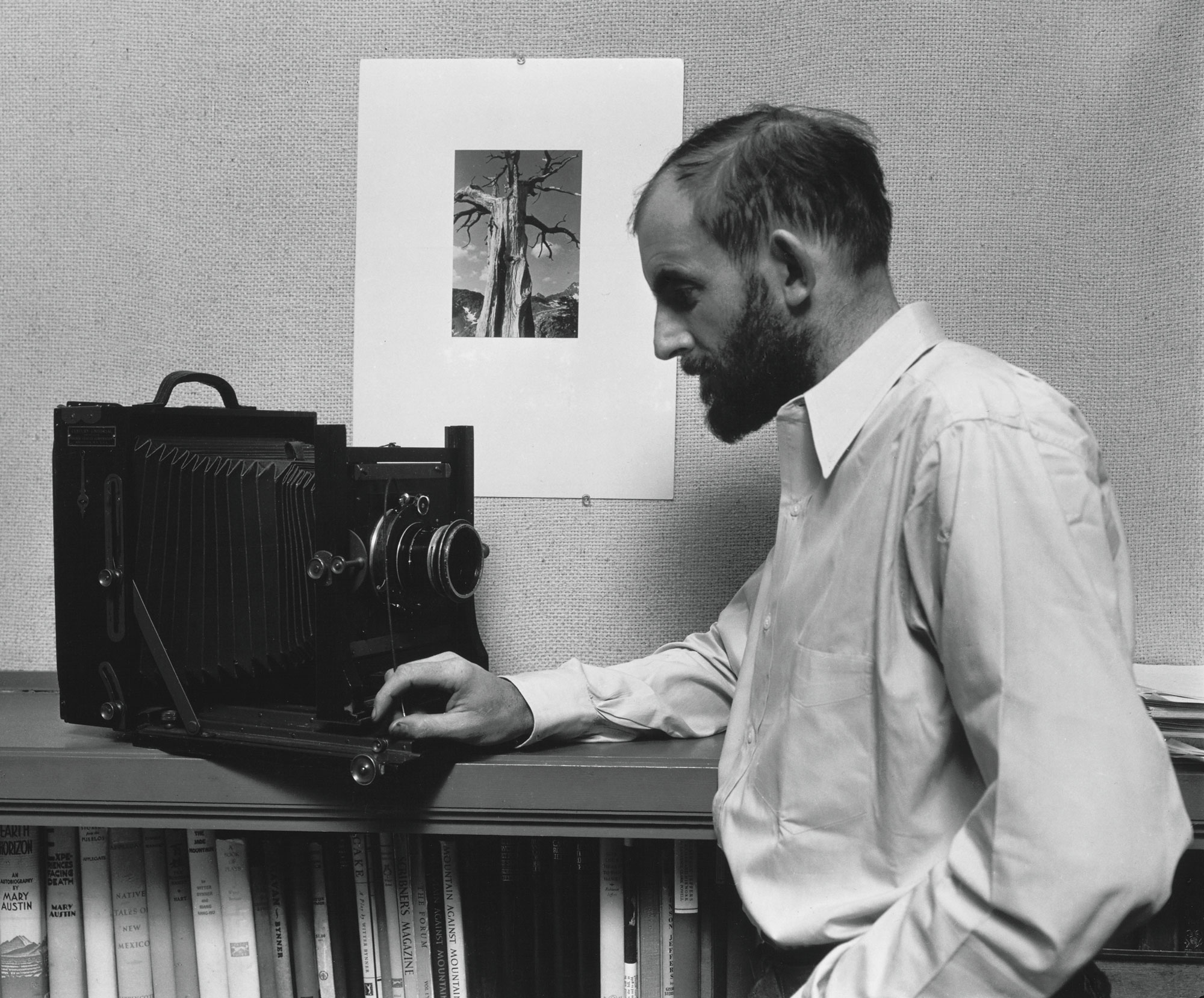

- Ansel Adams, self portrait.

- Portrait of O’Keeffe by Ansel Adams.

- Ansel Adams, “Dogwood Blossoms”, 1945 printed 1959, gelatin silver print, 9 5/16 x 6 7/16 inches, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. ©2008 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

- Georgia O’Keeffe, “Abstraction White Rose”, 1927, oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches, CR 599, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

- Left: Georgia O’Keeffe, “Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico | Out Back of Marie’s II”, 1930, oil on canvas, 24 1/4 x 36 1/4 inches, CR 730, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Right: Ansel Adams, “Winter Sunrise, the Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine, California”, 1944, gelatin silver print, 15 5/8 x 19 1/4 inches, The Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. ©2008 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

No Comments