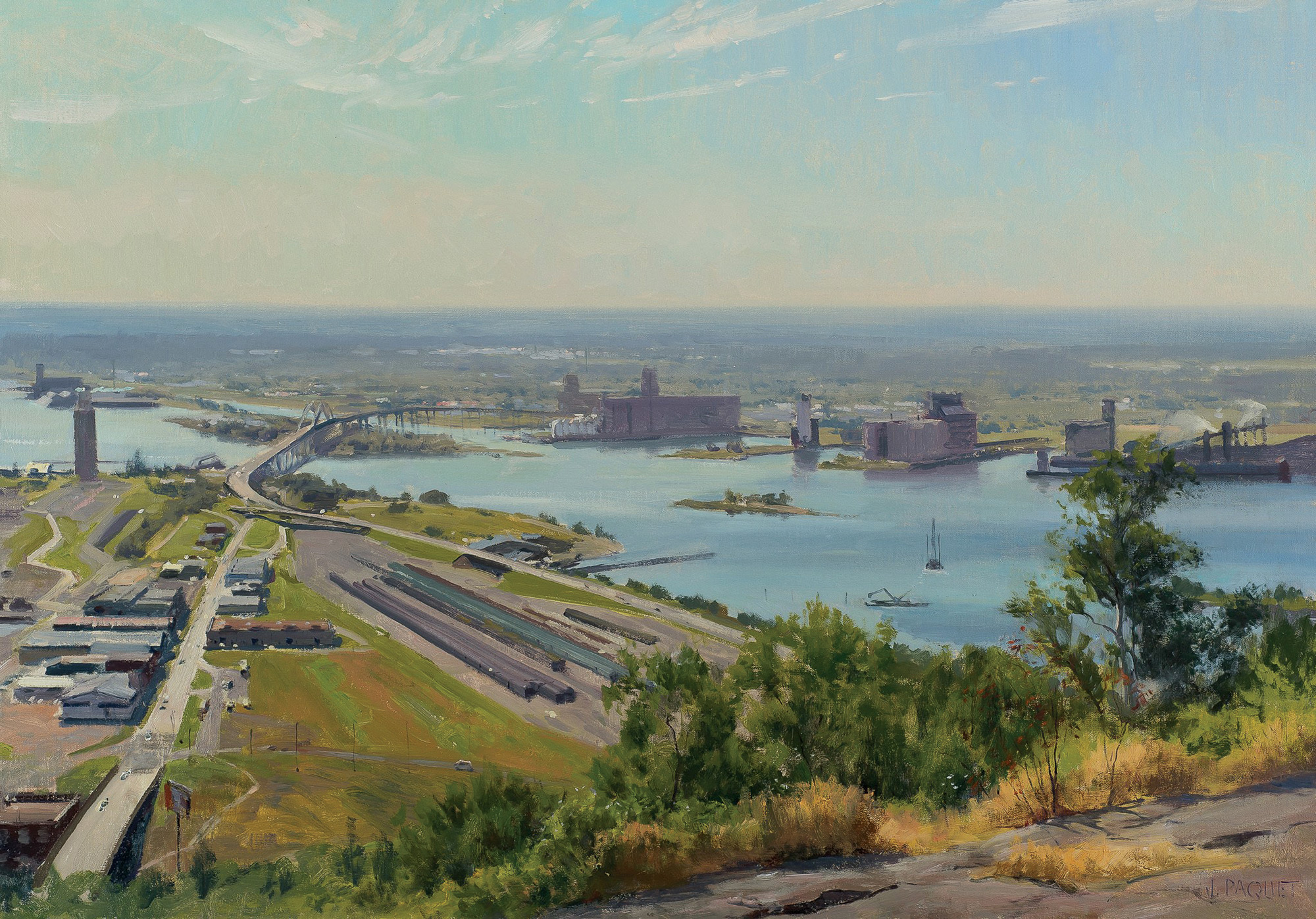

18 Jul A Record of Industry

IN A BETHLEHEM, PENNSYVANIA, CEMETARY, on a gray, sleety morning, Joe Paquet stood working at his French easel. The cemetery offered the best view of the subject Paquet had come to paint: a shuttered steel factory, silent as the grave markers surrounding him. As he painted in the numbing cold, Paquet became aware of an elderly man who had stopped nearby, watching for a long while. Finally, the man spoke without turning from the factory. “My grandfather worked there. My father worked there. I worked there,” he said. “We never thought it would end.”

Paquet recalls that morning to explain why he paints industrial landscapes. “It’s all disappearing so quickly. I want to capture this — not a fantasy — but this, what’s left,” he says. “I want to record history but also honor the people who built this country.”

Though not the usual subject matter for artists who derive their primary inspiration and income from painting landscapes, a number of contemporary realists have chosen to turn their attention to urban sprawl and industrial blight. Some paint scenes that are shuttered and decaying, others depict functional structures that are eye-sores or environmental problems without solutions, and others still create images of clean technology as it crops up in the natural landscape. The resulting paintings challenge both artists and patrons alike. Done in a way that finds beauty amid the chaos, they are the very thing that reaches beyond the mechanics of art into the realm of truth-seeking.

The idea of painting industrial America took root at the turn of the 20th century, most notably with the Ashcan artists, a group of Philadelphia newspaper illustrators who painted in the evenings with Robert Henri. They eventually followed Henri to New York where they took to the streets painting gritty, heavily expressionistic renderings of the day-to-day people and workings of the city. Guided by their journalistic instincts and Henri’s motto, “art for life’s sake,” this group of eight looked to the burgeoning working-class culture — the Bowery, seedy bars, brothels, boxing matches, dock workers, train yards and the like — and began painting the unromantic yet authentic version of what they saw around them.

What is there to say about industry today that hasn’t been splashed across the news, captured in-depth by photographers around the world, blogged about, and debated on the floor of Congress? In other words, why bother?

“As artists, we have to acknowledge where we are as a society,” says painter Joe McGurl. “If this had been 300 years ago, and we didn’t understand the science of photons, I’d have a different perception of light. Advances in science have given me a sharper focus, for example, on how light works in my paintings, how it moves through a scene. It’s subtle, not overt, but it’s there.”

McGurl’s recent work, Powerlines, depicts cables running above a cow pasture in Immokalee, Florida. A symbol of manufactured energy is set against the backdrop of ominous thunderheads, raising the question: Just how much of this do we control?

What an artist brings to this equation — the contemplation of science, industry and the advancement of society — is the opportunity for deeper awareness on the subject. It can even be an awareness that wasn’t originally envisioned at the onset of a painting, as was the case for painter Kate Starling.

“I grew up in Phoenix; everything is new, mine scaling piles are everywhere. It’s heartbreaking,” Starling says. “Painting is often a celebration of something, so it’s hard for me to paint what I’ve hated all my life. But then I drove past Nevada Solar One and it struck me as beautiful, seeing a field of solar panels reflecting the light in the same way a lake does. A lot of times, it’s man’s influence on nature that really moves me. It makes me want to say something to deal with the reality of where we are today.”

Despite the fact that artists often want to take on aspects of society they find disturbing, as was the case with the Ashcan artists, there is still the reality that these scenes push contemporary landscape artists and their patrons into uncomfortable territory. “This raises questions about beauty,” suggests artist Jill Carver. “I’m thinking of Paul Nash’s incredible images from the Second World War; the content is painful, but the vision is magical.”

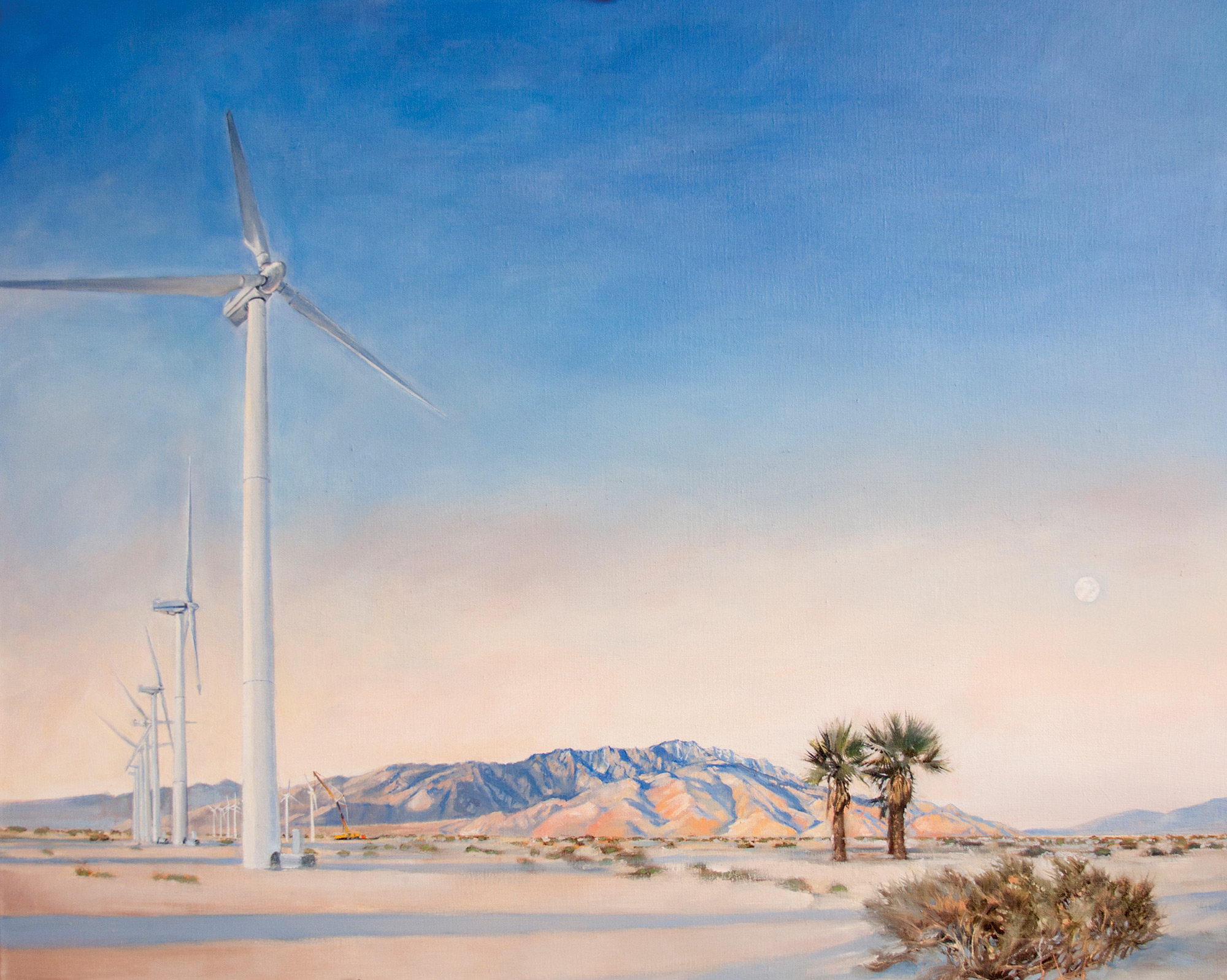

Of her own work, Carver prefers land untouched by man. But living in Austin, Texas — where construction is the hottest industry these days — she finds her perceptions are being challenged. “When those wind turbines first started dotting the landscape from Abilene heading all the way west, I thought it ruined the vistas, and I concluded they would never be deemed beautiful,” she says. “Then I drove right through the middle of a wind ‘ranch.’ It was magical being in the heart of it. Those turbines seemed magnificent, so huge, so graceful and silent.”

Don Stinson was inspired by another artist’s effort to make a statement. At the Amon Carter Museum, he saw the 1940 painting by Charles Sheeler [1883–1965] titled Conversation — Sky and Earth. Sheeler, famous for depicting the precise beauty of industrial subjects, painted transmission towers and wires against the backdrop of the Hoover Dam below a bright blue sky. The dam, completed four years earlier, was both the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant and tallest concrete structure at the time. The painting was part of a series of six commissioned by Fortune magazine in 1938 as a pictorial essay celebrating America’s industrial power, according to the museum.

Stinson was moved by Sheeler’s optimism for new, cleaner ways of creating energy. He incorporated this thinking in his own paintings, Giorgione Pass: Imagined Beginnings and All in Good Time, Train Station: Palm Springs, CA. Both works depict the Coachella Valley, where the first wind turbines were erected in 1982. Today, there are so many turbines they seem to create their own atmosphere, a sensation Stinson worked to capture in his paintings.

“The stark white beauty of the wind turbines’ sleek industrial design against a deep blue sky — clean energy set against a beautiful backdrop of clean air — suggests the possibility that, perhaps, a justifiable compromise has been reached here,” he says. “These places require both an awareness of great historical precedents in art and demand that I think differently in order to depict them in their full complexity.”

And yet, even as we tear down the old and outdated and strive to reinvent and renew industry across this country, there are many left behind. Artist Dean Mitchell has spent his career bringing awareness to the plight of people lost in time, held bound within desolate landscapes and poverty; scenes all too familiar to him, having grown up in poverty in the rural, segregated South.

Over the last several years, Mitchell has traveled to reservations in the Southwest where he turns an unflinching eye to the desperate conditions of Native Americans. “People’s lives are shaped and informed in these spaces and structures; they have psychological effects that can last for decades,” he says. “I have no fear of looking at the harshness of life through my work if I feel it needs to be seen for the betterment of humanity.”

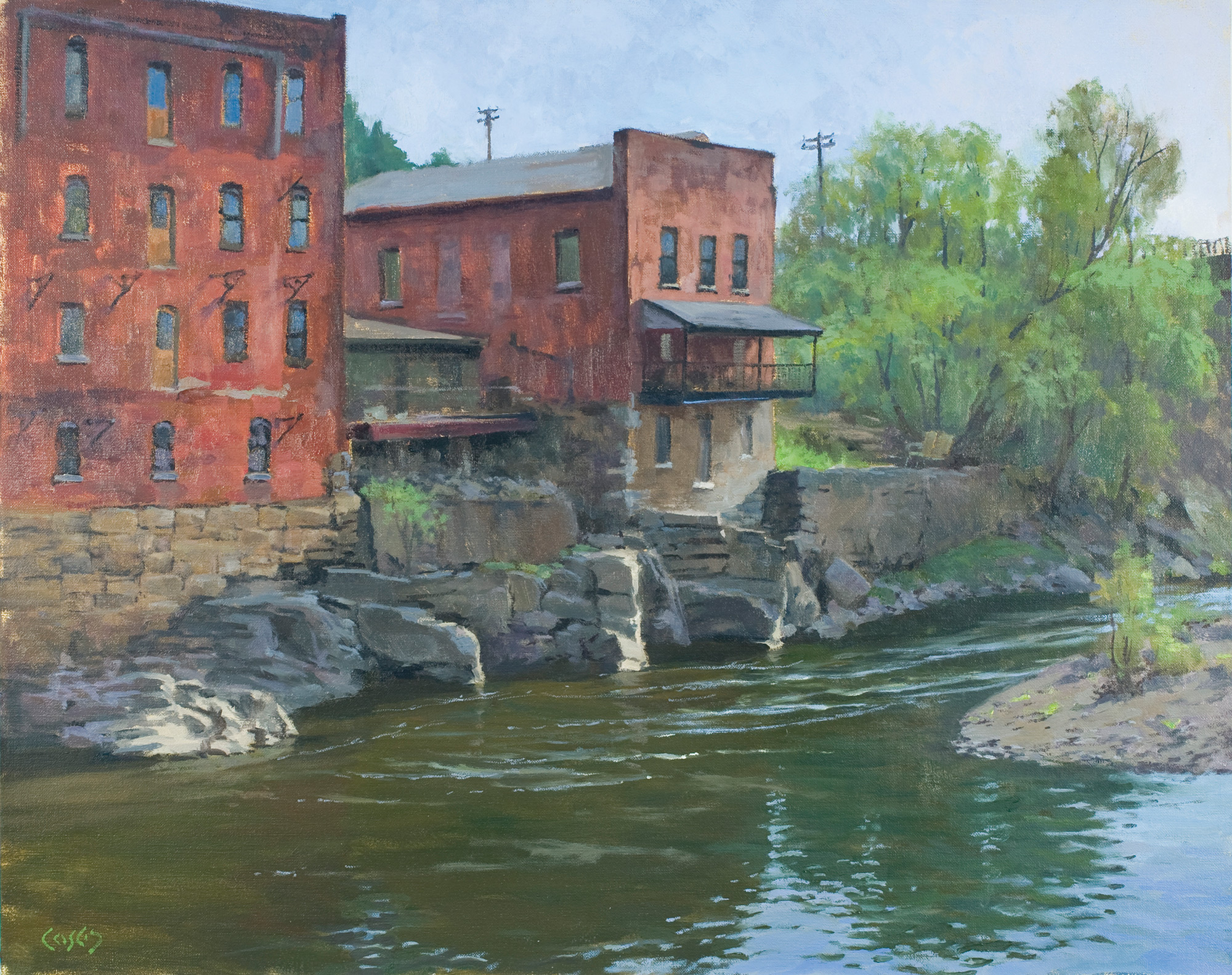

As with all things made by man, time is the great equalizer; no matter how hard we strive to maintain buildings, power lines and the mechanisms of industry, nature, ever patient, will work to reclaim the land. For John Cosby, erosion has become a fascination that has prompted him to travel the country, creating works such as Bedrock Buttresses and Bricks. Painted along the Mohawk River in New York, it depicts the last remnants of the industrial age there, in its current state of attrition. “The river brought bars and brothels and factories,” Cosby reflected. “Now the river is silently taking it all back.”

Editor’s Note: These works and others will be on display during America’s Industrial Landscape at the Tweed Museum of Art at the University of Minnesota in Duluth, September 19 through November 12, 2017.

- Joe McGurl, “Powerlines” (detail) | Oil on Panel |18 x 24 inches

- Kate Starling, “Solar Farm” (detail) | Oil on Linen

- Charles R. Sheeler, Jr. [1883–1965] | “Conversation – Sky and Earth” | Oil on Canvas | 1940 Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas; 2009.7

- Dean Mitchell, “Rotting in the Light” | Watercolor | 18 x 19 inches

- John Cosby, “Bedrock Buttresses and Bricks” | Oil | 24 x 30 inches

- Don Stinson, “Giorgione Pass: Imagined Beginnings” | Oil on Linen | 36 x 46 inches

No Comments