17 May Perspective: Frida Kahlo [1907–1954]

Long before Madonna and Lady Gaga made calculated self-invention into an art, there was Frida Kahlo. Long before social media and the ubiquitous selfie sent people’s faces around the globe, the Mexican painter was creating image after image of herself staring back at the viewer with a strong, direct gaze. And long before the cult of celebrity fed the insatiable public appetite for personal revelation, Kahlo’s story of pain, love and inner struggle found its way into her art.

Of course, knowing Kahlo’s singular image — heavy brows, Tehuana peasant dress, flowers atop her black braids — is not the same as knowing her art. And even recognizing her art, with its vivid colors, intimate self-portraits and often-unsettling imagery, does not equate to an understanding of her life and work within the cultural and political context of her times.

That crucial sense of context is what is often missing in the pop culture dissemination of Kahlo’s image, notes art historian Adriana Zavala, associate professor of modern and contemporary Latin American art history and director of Latino studies at Tufts University. In addition to writing a book about the artist, Zavala curated the well-received 2015 exhibition Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life at the New York Botanical Garden.

“I really appreciate that Kahlo opens a door for Mexican art and culture,” Zavala says of the phenomenon sometimes called Fridamania. “But I want people to begin to understand her in a more holistic and complex way.”

That understanding has to include the changes that were beginning to reshape Mexico around the time of Kahlo’s birth in Coyoacán — now a suburb of Mexico City — to a Mexican mother of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry and a German-born father. Although official records give Kahlo’s birth date as July 6, 1907, the artist claimed she came into the world on July 7, 1910, an entrance more closely coinciding with the start of the Mexican Revolution that would overthrow President Porfirio Díaz. The confluence of the personal and political was integral to Kahlo’s creative expression throughout her life.

Her artistic exploration began in 1925, at age 18, during a long period of convalescence from severe injuries after a trolley car crashed into a bus she was riding. Bedbound and in a full body cast for three months after the accident, she took up the paints and brushes her father gave her and a special easel she could use in bed. Her first paintings were self-portraits, a theme that eventually comprised at least a third of her life’s work, or about 55 paintings.

Although not trained in a conventional sense, Kahlo received valuable critique and encouragement over the years from internationally renowned Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, who was 20 years her senior and with whom she became infatuated as a schoolgirl. In 1927, she approached Rivera as he was painting a mural at the Ministry of Public Education. She showed him a couple of her paintings and asked if he thought she had talent.

He did, and Rivera became a frequent guest at her family’s home. They married in 1929. Despite a tumultuous relationship that included numerous affairs on both parts, divorce in 1939 and remarriage a year later, Kahlo and Rivera remained intense admirers of each other’s art. They lived at her parents’ home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), sometimes together and sometimes in separate quarters, until Kahlo’s death a week after her 47th birthday in 1954. Rivera died in 1957, and La Casa Azul became a museum dedicated to the two artists in 1958.

Kahlo’s artistic achievements remained largely overshadowed by Rivera’s reputation during her lifetime. In 1938, however, she received a solo show at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. The following year she traveled to Paris, where one of her paintings, The Frame, was included in an exhibition of Mexican art. The Frame was subsequently purchased by the Louvre, making it the museum’s first acquisition by a 20th-century Mexican artist. These and other travels, including trips to San Francisco, the Detroit Institute of Art and New York’s Museum of Modern Art with Rivera, underscore the fact that far from creating in a vacuum, Kahlo was clearly aware of art history and current art movements in Europe and the United States. She experimented with various modernist styles early on, even agreeing to paint a friend’s portrait as if it was a “Diego Rivera cubist portrait.”

“Kahlo was in artistic conversation, expressed pictorially, with Rivera and other Mexican artists and with international artists. People sometimes fail to see that she was a profoundly complex intellectual,” Zavala says.

French writer André Breton dubbed Kahlo a fellow surrealist, yet the artist herself saw her work as arising directly from reality. In the 2007 PBS film “The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo,” she described her paintings as “the frankest expressions of myself. Since my subjects have always been my sensations, my states of mind and the profound reactions that life has been producing in me, I have frequently objectified all this in figures of myself, which were the most sincere and real thing that I could do in order to express what I felt inside and outside of myself.”

Kahlo was part of the intellectual movement espousing Marxism and eschewing bourgeois values during the Mexican Revolution. The exiled Russian Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky was a friend and lover to Kahlo during the 1930s. In this political atmosphere, Kahlo’s decision to dress in indigenous attire represented a populist embrace of her country’s folk culture and ancient heritage. “The way she dressed and styled her home needs to be seen as an extension of the creative process,” Zavala says. “It was an artistic choice she made.”

While Kahlo was deeply influenced by Mesoamerican cultures and Mexican folk art, her approach diverged from those of many of her artist friends. A 1924 manifesto penned by Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros and signed by fellow muralists Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and others declared that art should “valorize Indian traditions and destroy bourgeois individualism,” according to art historian Nancy Deffebach in her book Frida Kahlo: Heroism of Private Life. Siqueiros’ manifesto also denounced easel painting as an elitist form of expression. The muralists supported an emerging nationalist narrative by celebrating the common man in public works of monumental scale. In this, Kahlo bucked the status quo even when its proponents were her peers. Her paintings remained intensely private and easel-sized, and they celebrated the individual, in the figure of herself.

At the same time, by incorporating pre-Columbian symbolism and employing the structure of traditional Catholic imagery in her work, Kahlo imbued her paintings with a “sense of myth,” as Deffebach puts it, that was both personal and much larger than herself. Kahlo had a spiritual worldview and may have believed in reincarnation, but she was firmly non-religious.

“Her self portraits as secular saint or profane goddess were a way of creating an alternative to the countless images of male heroes. Since spiritual power was one of the few types of power commonly attributed to women, she expropriated and transformed religious imagery as a way of legitimizing and empowering a female protagonist,” Deffebach writes. Kahlo also challenged convention by using painting to address what at the time were taboo themes, including miscarriage, female identity and sexuality, lesbianism, divorce and violence against women.

This unflinching quality of Kahlo’s work, along with a defiance of gender and sexual norms in her personal life, was among the traits that attracted attention to the artist in the 1970s. In the United States she became a symbol of emerging Chicano pride and identity, and in 1978 the Galería de la Raza in San Francisco presented an exhibition of Kahlo-inspired art. Throughout the 1970s, female art historians and feminists, including Lucy Lippard and Judy Chicago, considered Kahlo a figure of self-aware female empowerment ahead of her time. By the early 1980s, Frida fascination was soaring, boosted in part by a best-selling 1983 biography by American art historian Hayden Herrera and later by a popular film on the artist’s life.

Although Kahlo was known but not artistically influential during her lifetime, her posthumous fame produced widespread cultural reverberations on multiple levels and offered a spark of inspiration for many who came later, including American contemporary artist Kiki Smith. As Deffebach puts it: “Throughout her career Kahlo introduced new themes in art that challenged assumptions about what topics art can deal with, and she assiduously inserted a female viewpoint into artistic and national discourses. These acts are her most significant contribution and her greatest legacy.”

Editor’s Note: Opening July 10 at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Frida Kahlo: Through the Lens of Nickolas Muray presents Kahlo’s iconic visage — described by some as “almost beautiful” — from the perspective of a longtime lover, friend and confidant. The show features 50 photographs by the Hungarian-born fashion and commercial photographer, taken in the 1930s and ’40s during Muray’s off-and-on romantic relationship with Kahlo. The exhibition runs through September 11.

- Nickolas Muray, “Frida with Nick in her Studio” | Silver Gelatin Print | Coyoacán 1941 | Courtesy of the Nickolas Muray Archives and Guest Curator Traveling Exhibitions and the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

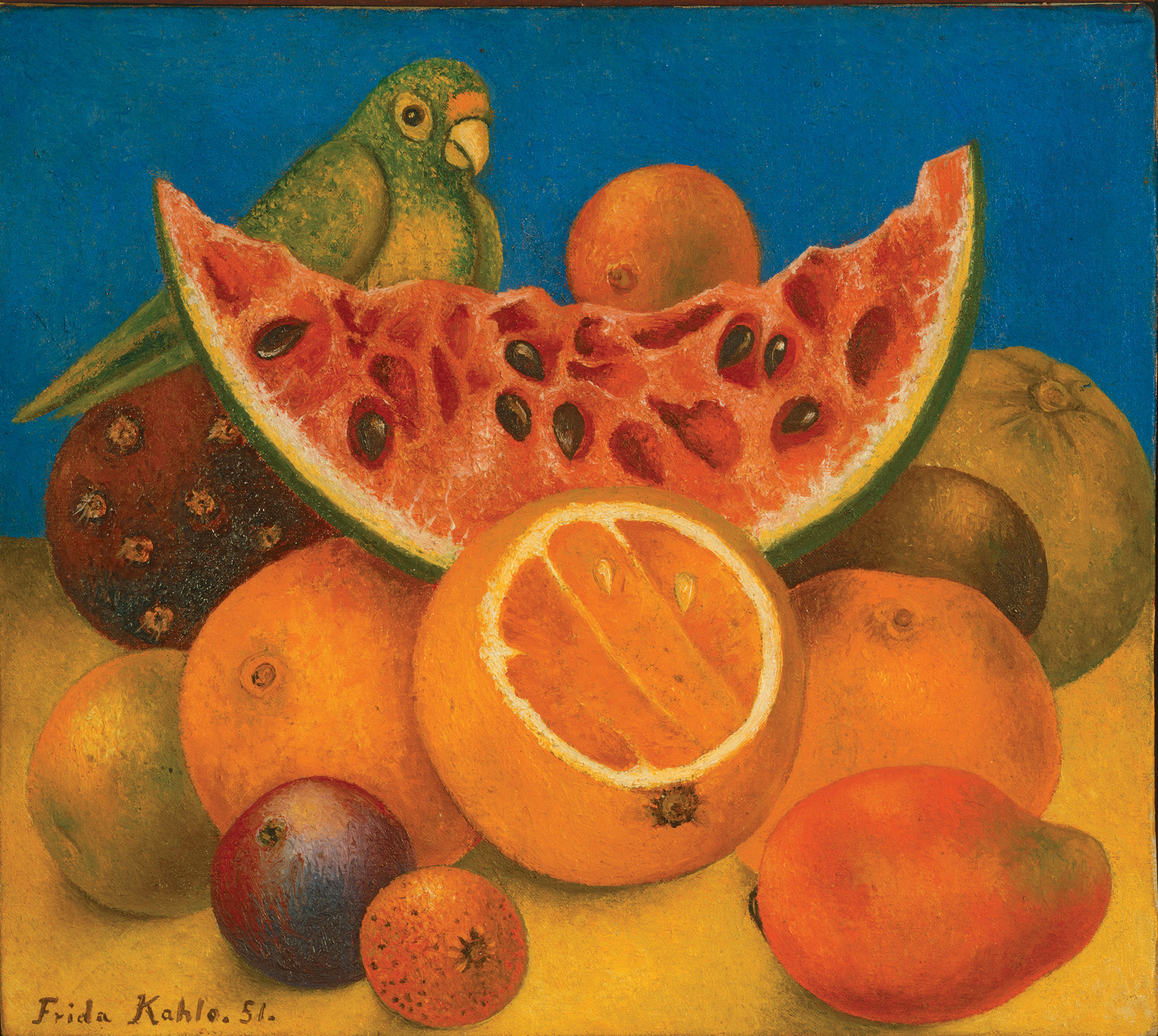

- Frida Kahlo | “Still Life with Parrot” | Oil on Masonite | 1951 Nicolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin | Photo: Erich Lessing | Art Resource, NY | © 2016 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. Artists Rights Society (ARS ), New York

- Frida Kahlo on a balcony above Detroit Industry murals. Photo: courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts

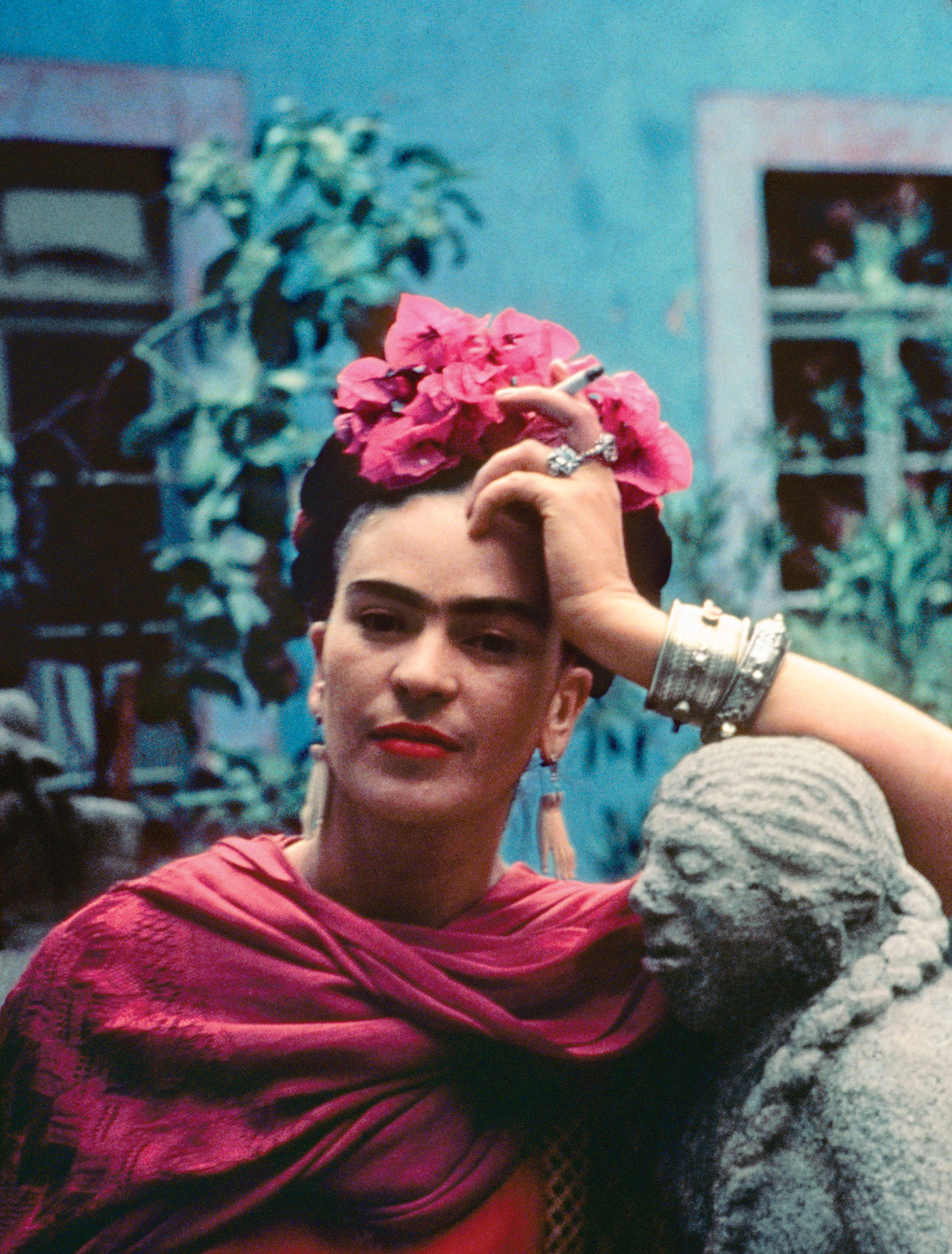

- Nickolas Muray, “Frida leaning on a sculpture by Mardonio Magaña” | Digital Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag Paper | Coyoacán 1940 | Courtesy the Nickolas Muray Archives and Guest Curator Traveling Exhibitions and the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

No Comments