28 May Perspective: George Catlin [1796-1872]

In one of the great ironies of his life, George Catlin was sometimes criticized for having too much sympathy for indigenous Americans, putting the artist out of step with the spirit of his times. Now, more than 140 years after his death, he is sometimes decried for having had too little sympathy, for exploiting the people he professed to admire.

If it seems Catlin couldn’t win, he probably felt the same way. The 19th-century painter’s ambitious goal was to create a visual record of as many North American tribes as possible at a moment in history when many of these tribes were on the verge of cultural collapse. Through his journeys west of the Mississippi in the 1830s and portrayals of the people he encountered, he produced enduring images that for generations have symbolized American Indians of the Great Plains. Yet as hard as he tried, he was unable to gain either the public support or government patronage he believed his work deserved.

Much about Catlin’s life is open to question, but what is undisputed is the gift he left to future generations: an extraordinary body of work he called the Indian Gallery. It consists of more than 500 paintings documenting 50 North American tribes. These include formal portraits and ethnographically accurate depictions of clothing, activities and lifeways, all based on the artist’s personal observations made on his subjects’ own terrain. It is the largest pre-photographic visual record of American Indians. Yet while the value of Catlin’s paintings as a window into a now-extinguished world cannot be denied, they have not always drawn favorable artistic appraisal, especially during his lifetime.

“He was criticized for the awkwardness of some of his figures, but if you think about going out into this place he’d never seen, what he did is really remarkable,” says Adam Duncan Harris, Petersen Curator of Art and Research at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. “A great way to think about him is as a proto-Impressionist. He was outdoors, painting his impressions of what he saw, so there’s a freshness and immediacy that doesn’t necessarily happen when an artist paints in a studio.”

Harris is guest curator of a traveling exhibition organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in collaboration with the National Museum of Wildlife Art, and is the author of an accompanying book. George Catlin’s American Buffalo features 40 original Indian Gallery paintings related to the buffalo and the animal’s integral place in the lives of early 19th-century Plains Indians. The exhibition is on view at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, its final scheduled venue, through August 30.

Paintings from Catlin’s second major body of work, created in the 1850s and ’60s, were showcased in a recent exhibition at the Sid Richardson Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Take Two: George Catlin Revisits the West was guest curated by Brian Dippie, Ph.D., professor emeritus of history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Dippie, the author of several books on Western American history, including George Catlin and His Indian Gallery, describes Catlin’s art as “not polished but tremendously appealing.”

There was reason behind his fresh, unvarnished style. Born in 1796 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, one of 14 children of Putnam and Polly Catlin, George is thought to have been self-taught in art. His father persuaded him to go into law and for a short time the younger Catlin worked in that field. But art commanded his attention more than law. In 1821 he gave up his practice, moved to Philadelphia, and soon was receiving portraiture commissions for such figures as Texas politician and soldier Sam Houston and Dolley Madison, wife of former U.S. President James Madison.

A few years later, Catlin’s first glimpse of Native Americans catalyzed his desire for more meaning in his art. A delegation of Indians stopped in Philadelphia on their way to Washington, D.C. The painter found himself enthralled by their “classic beauty.” Aware that their way of life was in grave danger — among other threats, the 1830 federal Indian Removal Act had just been signed into law — Catlin determined to visit and paint as many tribes as he could.

That monumental task was begun with the aid of General William Clark, whom Catlin had met in St. Louis. The artist convinced the former explorer to take him up the Missouri River and introduce him to tribes, including the Sauk, Fox and Sioux. Then in 1832, an 1,800-mile steamboat journey up the Missouri to Fort Union resulted in a wealth of paintings, as well as the start of an enormous collection of artifacts. It was followed by three more summer expeditions farther into the heart of Indian Territory. Catlin carried rolled canvases and oil paints and worked rapidly, producing hundreds of sketches and paintings, along with color notes and written accounts. “He always said it was a race against time to preserve this visual record, and that he had to be forgiven for any (artistic) deficiencies,” Dippie says.

Indeed, the landscapes in many of Catlin’s paintings are indicated simply with broad brushstrokes. Depictions of buffalo hunts and other activities often rely on oil-sketch shorthand for quickly moving figures. Other images, especially of ceremonial or daily life, are more detailed.

The artist’s American Indian portraits are clearly the most carefully recorded, with close attention to clothing, adornment and ceremonial objects, along with distinctive facial traits. “His abilities as a portrait painter are evident. He captures individuals, not just costumes,” Dippie says.

Catlin was a prolific writer as well as a painter. His 1841 book, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, was reprinted numerous times. In it, the artist seems almost prophetic in his elegiac, melancholy descriptions of both Indians and buffalo. They were, he wrote, “joint and original tenants of the soil, and fugitives together from the approach of civilized man … ” Catlin had a “complicated mindset,” Harris says. “On one hand he wanted to preserve their way of life and the buffalo, but at the same time he was sure they were doomed.”

Crowds lined up to see Catlin’s Indian Gallery in New York City in 1837, and then in other cities along the East Coast. But the public’s interest soon faded and the artist, by then with a wife and child to support, was falling increasingly into debt. Yet he was obsessed with keeping his oeuvre intact. He tried to sell the Indian Gallery to the U.S. government — the first of multiple attempts — but Congress, as Catlin put it, responded with “unfastening hands.” So he took his exhibition to England and Europe, along with crates of buckskin and fur, leggings, moccasins, war clubs, pipes and other objects.

Initially he was warmly met, received by Queen Victoria in London and King Louis-Philippe in France. But once again the public’s interest dwindled. This time Catlin turned to showmanship, adding the thrill of live dances, chanting and even displays of scalping techniques by troupes of Ojibwa and Iowa Indians. While contemporary thought frowns on this type of Wild West show, Dippie reminds us that Catlin lived in a different age with a very different worldview.

In 1852, when even the live Indian shows no longer brought in enough money, Catlin found himself bankrupt in a London debtor’s prison. A few months later, a wealthy Pennsylvania businessman paid off the artist’s debts and acquired the Indian Gallery and artifacts, which were shipped to Philadelphia and placed in storage. Meanwhile, Catlin set off on voyages to South America and up the Northwest Coast to Alaska — or at least, he claimed to have done so. The middle part of his life constitutes what Harris calls the “murky period.” Catlin created paintings of South and Central American Indians and wrote accounts of his adventures. Unlike his 1830s travels, however, there was no one to vouch for the validity of his claims, which rest solely on his word. Historians have attempted to find verifying records, but as Dippie puts it: “Independent corroboration awaits discovery.”

What we do know is that Catlin created a second large body of work he called the Cartoon Gallery, painted in Europe and America during the 1850s and ’60s. About 300 paintings, or half of this second collection, are replicas of works from the Indian Gallery. Catlin recreated them by tracing the pen-and-ink drawings that illustrated his books, which were based on his original paintings.

In another ironic twist, the U.S. government today is steward of most of Catlin’s work. Seven years after his death, the Indian Gallery was donated to the United States National Museum (later renamed the Smithsonian American Art Museum) and the bulk of the Cartoon Gallery is now housed in the National Gallery of Art.

A version of another of Catlin’s cherished dreams was realized shortly before his death. The painter wrote passionately about wanting to create a protected reserve where Indians and buffalo could continue their way of life. It would be, he wrote, “… a nation’s Park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!” As Harris points out, this concept may strike us today as “a kind of sideshow for the amusement and edification of presumably European-American onlookers.” Yet many credit Catlin with the idea that became the national park system. Yellowstone National Park, the country’s first, was established a few months before his death in 1872.

“For all the criticism directed at Catlin, especially the modern, rather trendy critique that he was an exploiter, his legacy was absolutely priceless,” Dippie says. “He was a dreamer, but he knew that one day posterity would demand a visual record of the First Americans, and he created it.”

- “Back View of Mandan Village, Showing the Cemetery” | Oil on Canvas | 1832 | Smithsonian American Art Museum

- “Crow Lodge of Twenty-five Buffalo Skins” | Oil on Canvas | 1832 – 1833 | Smithsonian American Art Museum

- “Ee-áh-sá-pa, Black Rock, a Two Kettle Chief” | Oil on Canvas | 1832 – 1833 | Smithsonian American Art Museum

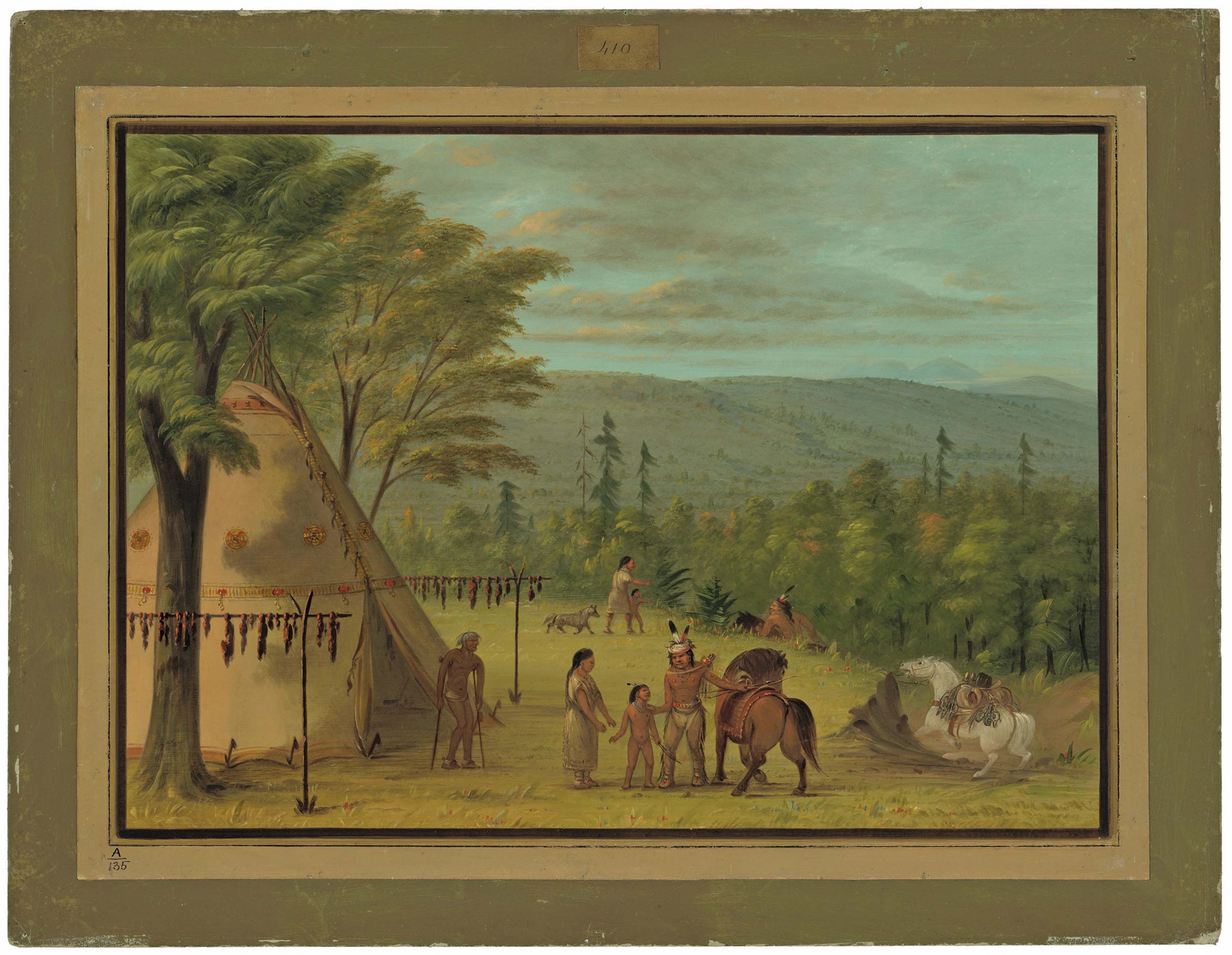

- “The Cheyenne Brothers Starting on Their Fall Hunt” | Oil on Card Mounted on Paperboard | 18.125 x 24.4375 inches

.jpg)

No Comments