14 Sep A Centennial in the Hallowed Halls of Salmagundi

THOMAS MORAN WAS AT THE HEIGHT OF HIS EARTHLY REPUTATION — 78 years old and still a decade shy of passing into the twilight of artistic immortality. Half his lifetime earlier, Moran had gone west from New York City to chronicle the fading frontier for posterity, his works momentously forming the basis for Congress setting aside Yellowstone as the first national park in the world. Trained in the tradition of the Hudson River School and acclaimed for his signature interpretative style of romantic realism, Moran also painted the Grand Canyon, Yosemite Valley and other scenic panoramas treasured today as American masterpieces.

When the time came for Moran to reflect on which of his many achievements delivered personal satisfaction, he penned a note in longhand from his home in East Hampton, New York, on June 8, 1915. The occasion has him being named a lifetime member in a certain Greenwich Village-based arts fraternity. “I cannot express the very great pleasure that it gave me; I consider it the greatest honor that I have ever received in my long career in art,” he wrote. “And to receive it from the most artistic association in the whole country is indeed a great honor.”

Some readers here may have never heard of the Salmagundi Club, but for many generations of mostly representational painters and sculptors, membership commanded the same vaunted prestige as entrance into the best salons of Paris. In fact, the West as we know it today, reflected in fine pictorial art, is tied to a fold of artists who proudly called themselves “Salmagundians.”

“Here, in this architectural gem of a building, we have — in many ways — the birthplace of Western art,” says Tim Newton, Salmagundi’s CEO and board chairman.

In November 2017, and continuing for several months, Salmagundi begins celebrating its 100th year in a building that cements its venerable gravitas. For Newton, the sense of transcendent belonging is what remains the greatest calling card for an organization that has endured changing times dooming other organizations. Salmagundi, he notes, has entered a new era of revival and modern relevance.

Originally, the club was founded as a sketch class held in sculptor Jonathan Scott Hartley’s studio. That year was 1871, ironically the same year Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson joined the Hayden expedition in Yellowstone to document its scenic marvels.

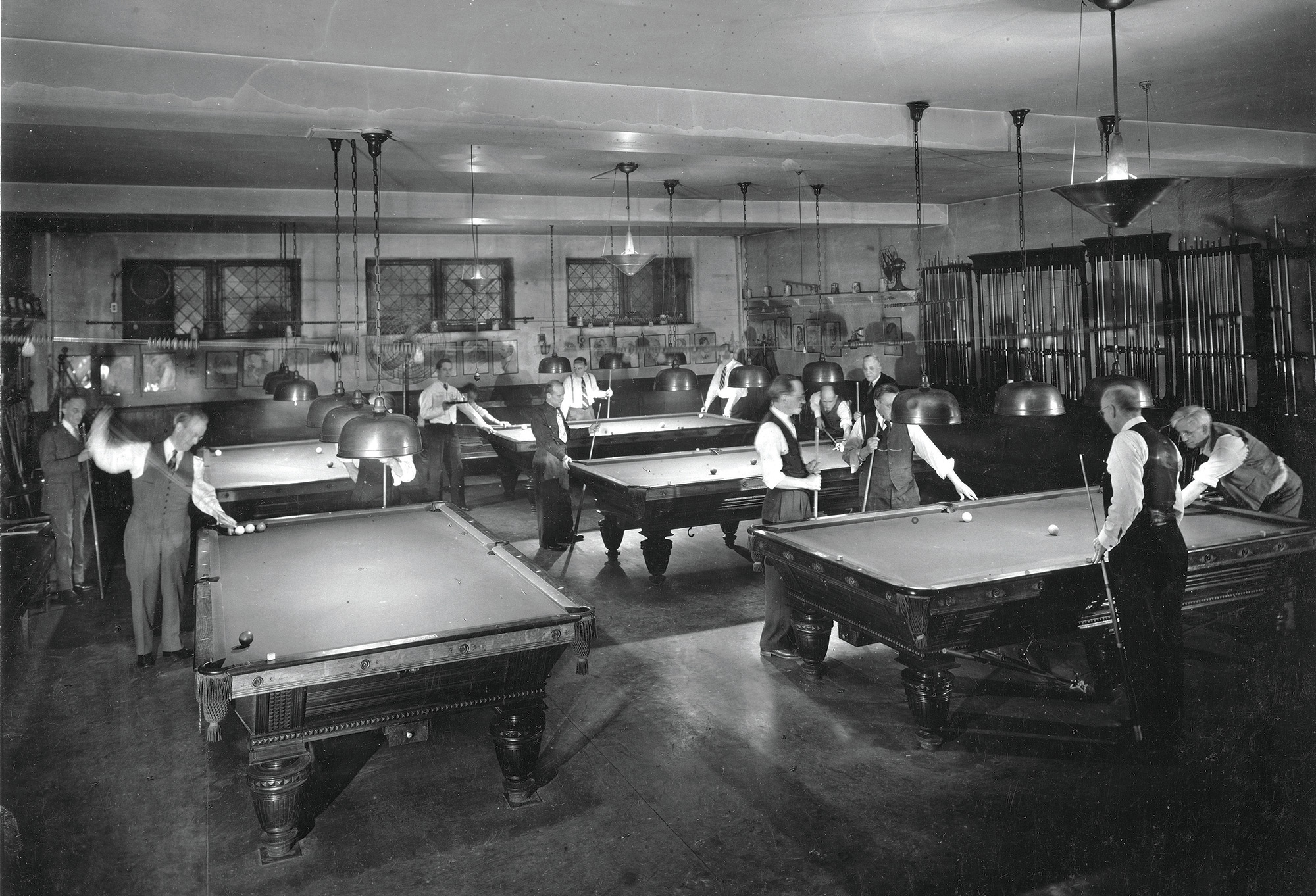

Salmagundi headquarters, located in a Brownstone at 5th Avenue and 12th Street, is a landmark set among landmarks in a neighborhood that The New York Times dubbed “the Gold Coast.” When the wooden floors at Salmagundi creak, when the smell of paint wafts, when members celebrate a sale by having a drink with friends or the cue ball makes a break on the pool table, it is not hard to feel transported back in time to the golden age of Realism.

Newton describes Salmagundi as an oasis against the whims of time. As one of the oldest arts clubs in the country, it has been a smoky gathering spot for collegiality, a place of mentorship, critiques and talking shop, a hub where successive waves of famous local and visiting American artists have passed through. That was, and in a profound way still is, the essence of Salmagundi membership.

Here is a smattering of those who graced the halls of Salmagundi, their visions appearing before millions on the covers of books and magazines, in advertisements and, of course, as works hanging in the most reputable museums. Here the cliché applies, “if only these old walls could talk.” Howard Pyle and many of his prized students, such as Philip R. Goodwin, N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn and Dean Cornwell were members. So, too, were William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam, Louis Comfort Tiffany, A.B. Frost, Ernest L. Blumenschein, William Herb “Buck” Dunton, John Clymer, Robert Lougheed, Charles Livingston Bull, Maynard Dixon and Norman Rockwell. Even sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was a member. The club has an in-house collection of more than 1,500 works created by its legendary faithful, a cache that could fill a wing at the Metropolitan.

So coveted was membership that John Philip Sousa, the noted American composer, cherished his honorary status given in 1904 and glee rose in Winston Churchill, a decently competent amateur painter, who received notification of his honorary approval in 1958. Long considered an old boys’ club, Salmagundi only admitted women in the late 1960s after the city of New York threatened to pull its liquor license. Today, women play key roles in leading Salmagundi forward.

Social organizations everywhere are struggling to maintain membership. Younger generations aren’t “joiners” the way their predecessors were. Fine art museums are toiling to stay relevant. Gallery scenes, once vibrant, are confronting an existential battle against online commerce and digital devices that short-circuit old face-to-face avenues of how painters and sculptors used to gather. On top of it all, the demands of modern life leave people with less time to maintain personal connections.

“What impresses me most about Tim Newton is that he and his colleagues refused to let Salmagundi fade, to become a casualty because he realizes more than ever it is an important touchstone,” says Canadian-American wildlife painter Dwayne Harty, who points out that his hero, Carl Rungius, considered North America’s finest wildlife painter, had been a Salmagundi stalwart.

Newton first strolled into Salmagundi 15 years ago, finding its galleries, salon spaces and billiard lounge in a state of neglect. Undeterred, after he began volunteering his time, he convinced Salmagundi members around the world that it was time to mount a rally. “Growth and changes at the club during this time of renaissance has been very much a team effort and there are many who’ve worked hard to achieve the current success,” Newton says. In just a decade, Salmagundi membership has doubled from around 500 to more than 1,000.

“Salmagundi has a tradition you can’t buy, nor could you replicate it,” he says, reminding of the role it played as a nexus for Salmagundians who brought the same kind of collegiality they knew in New York to emerging art colonies. Some include those affiliated with the Taos School and enclaves that sprang up around Santa Fe, New Mexico, Tucson and Scottsdale Arizona, and Pasadena, California.

“Tim’s belief is that heritage and history still matter, and you can feel it in the vibe of its working building,” Harty says. “Where else can you find palettes on the wall that belonged to some of the greatest American artists who ever lived and probably still have their DNA on them? Or flip through art books they held in their hands — American Impressionists studying the works of their French counterparts?”

Every year, Salmagundi awards its Medal of Honor, with recipients over the last century and a half representing a who’s who of art history.

“What Salmagundi represents is special and I don’t know of any other that can match it,” says painter Sherrie McGraw, a renowned portrait artist living in Taos, New Mexico. “I probably wouldn’t be a member if it weren’t for Tim Newton. He came in and reassured the existing club members that it could be a vital place where a lot of things could happen for artists but most importantly that they — just as the famous ones who came before — play an important role in adding to the spirit of the place.”

It was a truth absorbed in the romantic heart and soul of Thomas Moran, who served as Salmagundi’s fourth president from 1893 to 1896. Newton says the building’s centennial show in November and subsequent events celebrating its classic home would win Moran’s approval.

“What we still have here is a space of refuge. In a city that is often frenetic and overwhelming, you can step in the front door of this club and gain solace and break bread with your peers, the same as some of the greatest artists in American history did before you. Imagine the stories that Moran told about his painting of the West,” Newton says. In Salmagundi’s hallowed halls, he notes, you have a tangible connection to real giants and to the new ones being born.

- Dinner tendered to Frank Tenney Johnson by Samuel T. Shaw at the Salmagundi Club, March 6, 1924.

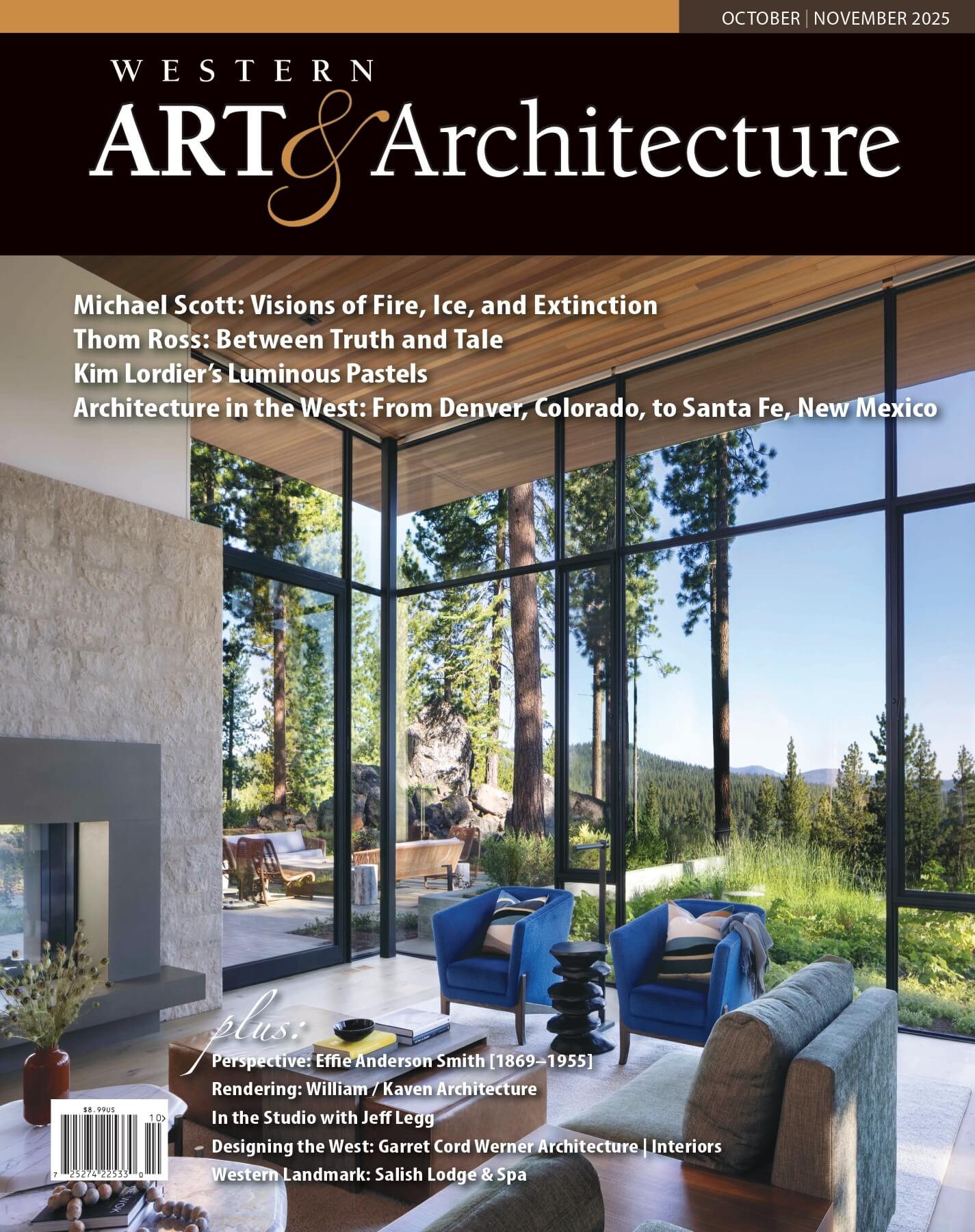

- The restored, rennovated gallery.

- The Salmagundi Club offers art classes, exhibitions, painting demonstrations and art auctions throughout the year for members and the general public.

- The billiard lounge today, and years ago, has always offered a setting for camaraderie amid artistic expression.

- The billiard lounge today, and years ago, has always offered a setting for camaraderie amid artistic expression.

- Devoted supporters Jan and Gus Gusman stand in the elegantly refurbished Patrons’ Gallery at the Salmagundi Club, which remains a temple for the tradition of American Realism, a touchstone for Western art and a quiet sanctuary for reflection in New York City.

No Comments