01 Sep An Integrated Life

THE BRIGHT LIGHTS OF THE DALLAS-FORT WORTH AREA yield to authentic Texas countryside not far west of the city. Within minutes of leaving the Forth Worth stockyards, the urban bric-a-brac of gas stations and convenience stores give way to open space, low hills and scrub. By the time you’ve crossed the Brazos River, a name associated with Charles Goodnight’s cattle drives and immortalized in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, you know you’re in Texas.

Approach the historic town of Weatherford, however, and you know you’re in horse country. The picturesque town boasts more than 60 turn-of-the-century homes. A stunning Second Empire-style county courthouse, built in 1886, commands a top-of-the-hill vantage point of the surrounding countryside. On the outskirts of Weatherford, however, and for miles in every direction, most available land seems to be given over to equine pursuits: horse pastures, riding and roping arenas, barns, outbuildings and miles of fencing enclosing grazing quarter horses.

“Weatherford is the cutting horse capital of the world,” explains Western artist Buckeye Blake. Blake, who was born in Arizona into a rodeo family and lived most of his life in Montana, should know. It was cutting that brought him and his wife, Tona, to visit Weatherford, and cutting that kept them here year-round. It was cutting that brought their artist son, Teal, to Weatherford. Now the Blakes, including Teal’s wife, Joncee, a graphic designer, live just a few miles from each other, their lives intertwined through family, art and, of course, horses. “We all followed our horses,” admits Buckeye.

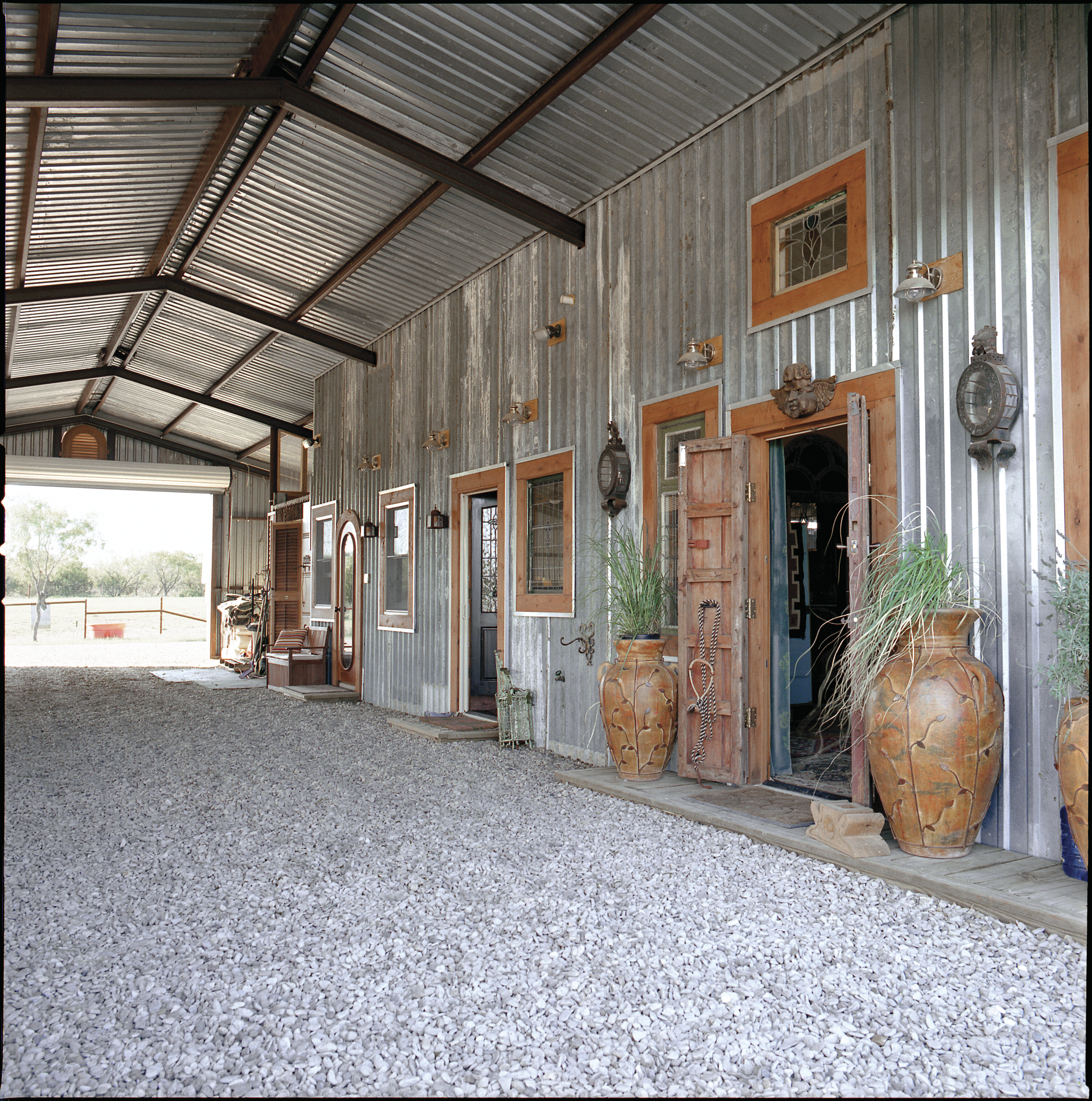

The couples’ lives are so closely aligned, in fact, that both live in homes that are half house, half barn. The tin-roofed structures are connected by a shared roof with an alleyway down the middle through which one can drive a truck and trailer. (This comes in handy during Weatherford’s fierce hailstorms, according to Buckeye.)

Buckeye and Tona’s 13-acre property encompasses the house/barn, horse pastures and a separate studio for Buckeye’s work. Their Texas lifestyle was not planned, but rather happened organically, recalls Buckeye. “We’d come down for the winter to get out of the snow in Sun Valley. We’d haul our horses down then stay through the winter months. We decided to buy some land. We thought we’d build a straw bale house, but we were worried about it being too damp here. We got all this tin from someone’s roof and thought we’d build a barn.” Once it was built, he says, “We decided we’d just live here.”

The Blakes’ living quarters are minimal, but never cramped. “We didn’t use an architect,” explains Tona. “We just did as we went. Buck and I had a whole pile of stuff: doors and windows and antiques. We just built around them. Our contractor was a roper who had never done anything like this before.”

The home has multiple doorways from the central alleyway, which offers a perfectly shady hangout for the Blakes’ five dogs. Each door and window is vintage or reclaimed, and interestingly framed or accented with unusual carvings, vintage doorknobs and ironwork items. The kitchen, a Bohemian-cozy cross between working food prep area and hangout, features wood cabinets and hanging stained-glass panels, circa 1910. The sitting room is furnished with Tona’s mother’s antiques, some of it 19th-century Dutch, collected over a lifetime in western Pennsylvania.

Throughout the dwelling are items sourced at Round Top, a famous Texas antiques fair, Tona’s photography, Buckeye’s paintings, Mexican folk art, family photos and layers of texture and color provided by carpets, cowhide, upholstery, pillows, painted walls, tramp art and unique lighting, including a crystal chandelier from Europe and a large hanging fixture from Morocco. A bedroom alcove is partitioned off by two pairs of carved doors; there’s a pair of blue painted doors from Afghanistan with a Tibetan carving built in over them. Of their eclectic style, Tona laughs, “I call it gypsy-Western.”

The Blakes spend much of their time — especially when entertaining, which they do frequently — under the portico, a comfortable seating area looking out over a terrace with fountain, native landscaping such as pampas grass and flowering sage, and, in the distance, quarter horses grazing amongst live oaks. The space is shaded by a tin roof with log beams, delineated by handcarved pine posts from New Mexico, decorated with bird houses and furnished with willow chairs and colorfully upholstered settees. Rain doesn’t keep them inside, nor do cool nights; Tona simply turns on heaters and illuminates tiny white lights along the top of the mesquite fencing.

Buckeye’s studio is just a short stroll away, in a reconditioned guard shack relocated from its site along the Brazos River. He built the wraparound porch himself. “I liked the shape of the roof,” he explains of his choice. “Old buildings have so much more atmosphere, though I should have made it six times bigger. I find if I have a small studio it dictates what size art I do. Also, I have lots of books and no storage, so I spend half my time looking for stuff. Ideally an artist needs an auditorium, with lots of room and a high ceiling.”

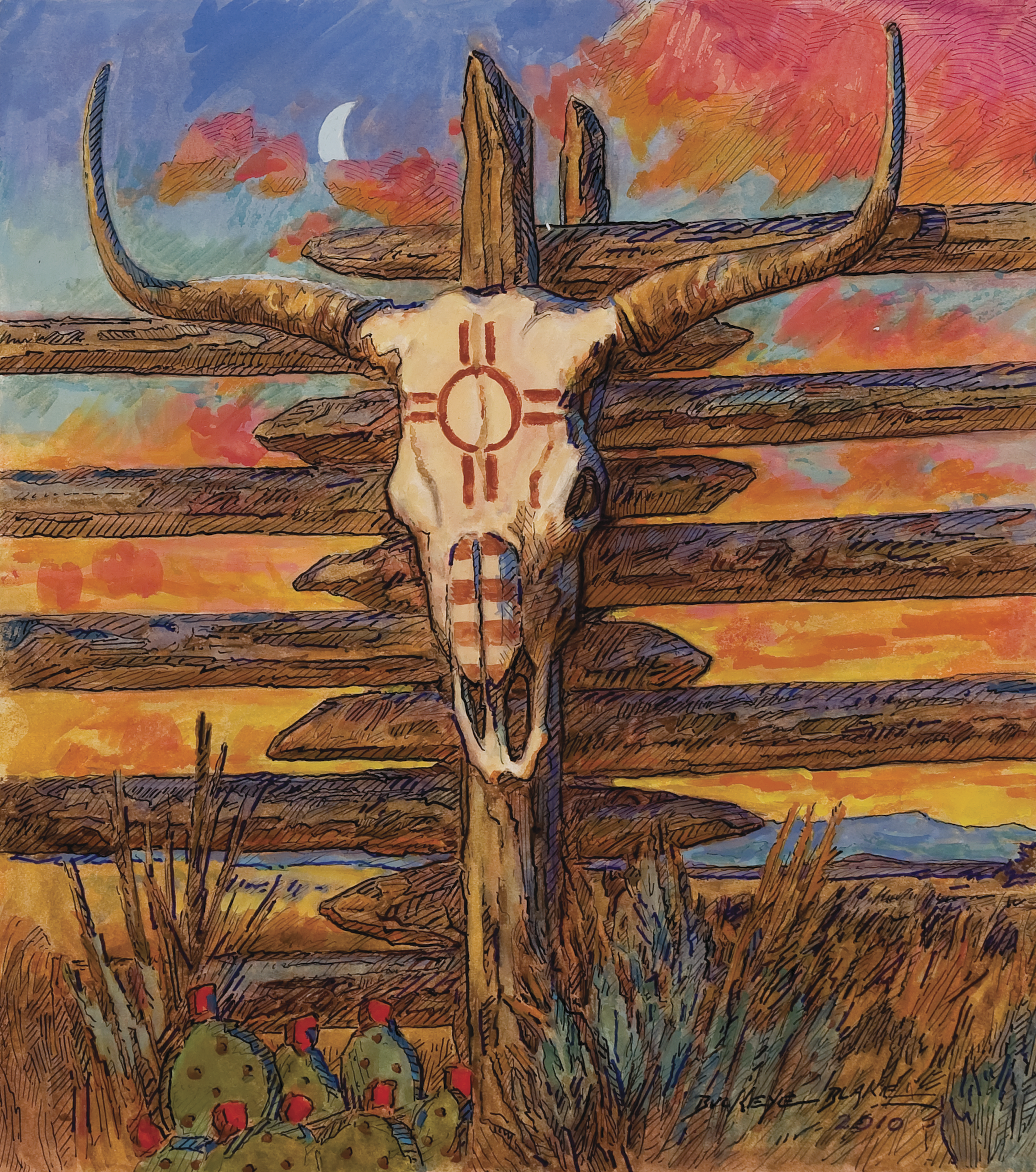

The one-room studio is charming and authentic, filled with books, skulls, paintings, an easel with work-in-progress, comfortable seating, a colorful painted door and a sink and washing-up area. References to the rich Texas history that inspires both Buckeye’s and Teal’s art abound, in books and photos and stacked artworks. “Texas has a fascinating history and [Texans are] proud of their Western heritage, from cattle drives to Civil War history. Teal and I both read a lot about the old cattlemen, Indian wars, bandits and outlaws. We’re 25 miles from the start of the Goodnight-Loving Trail, and three hours from the Pitchfork Ranch, which is one of the largest ranches in the U.S.”

Teal, who attends ranch rodeos and helps cowboy on the Pitchfork to stay in touch with his subject matter, explains, “The Pitchfork Ranch is 800,000 square miles. It’s rough country. You live on the chuckwagon for several days, and the remuda has 100 horses. A lot of the kids down here go from ranch to ranch making $100 per day. They carry their saddles with them. Their gear is authentic and they work hard. They all live out of a range tepee and their bedroll.” Working among old-time cowboys, he says, “gives inspiration and it helps with my clarity.”

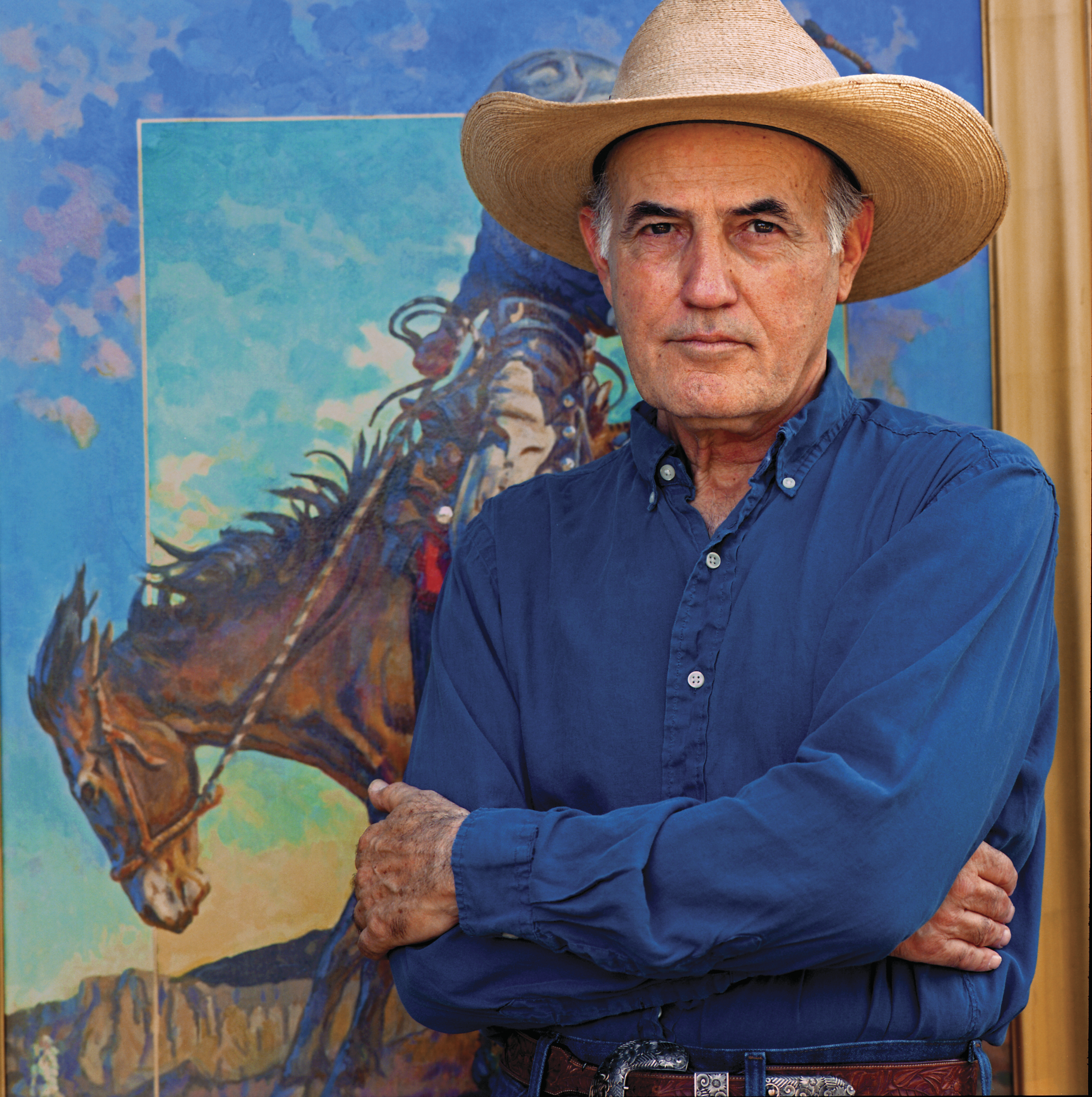

Buckeye is known as a painter of landscapes and Western scenes. He is also known for his posterlike works, paintings with lettering that recalls the classic tourism posters during the early days of Western railroads. But Blake is a fine-art sculptor as well. His life-size bronze of Kit Carson resides in front of the Supreme Court Building in Carson City, Nevada, while a similarly scaled sculpture of Charlie Russell and his horse, Monte, can be viewed in Great Falls, Montana. His graphic designs appear on soda bottles and dinnerware; he’s even designed iron gates for a private ranch. Represented by many galleries, in 1994 he was the subject of a one-man retrospective at the Whitney Gallery of Western Art at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming.

Teal Blake’s subjects speak of the ranching lifestyle: cowboys working cattle or roping horses, or jackrabbits racing across the sage-covered plain. Growing up in rural Montana, he recalls “I was into animals; I was always catching snakes and critters. I thought I’d go into zoology. Then I got into fly fishing and thought I’d be a guide.” In college Teal studied architecture and took life drawing and anatomy classes. Later he took an intensive painting class at the Scottsdale Art School. “What I learned more than anything was that it’s a matter of putting the time in.” He’s been pursuing art full-time since 2003. In 2009, Teal Blake won Best of Show and took first place in watercolors at the prestigious 34th Annual Phippen Western Art Show for his painting of saddled horses in a red trailer. Now, he says, “I make my living being an artist, and it’s what I love to do.”

As Buckeye puts it, for both artists their pursuit “is about the West and knowing what you’re painting, but it’s also color and shape and design. That’s really what you’re doing, whether you’re painting a person in the country or a building in the city. Color, light, shadow, harmony — that’s the artistic process that’s really exciting.”

Being immersed in it, however, the Western subject matter is as natural to the Blakes as, well, the horses they live amongst. As Buckeye reflects, “If you’re raised in it — I was, Teal was, my father was — it’s the West and it’s what you know. It helps to paint what you believe in; that comes across in the finished work. You’re emotionally connected.” And when you have a connection to your subject matter, he adds, “You have a passion for it.”

- Amidst the structure that is home and barn for the artist, Buckeye Blake prepares to groom one of his horses.

- Teal Blake, “Texas Half Top” | Watercolor | 16 x 22 inches

- The home is filled with cozy nooks for everyone to enjoy.

- Artist Buckeye Blake and his wife, Tona, built their half home, half barn to reflect their animal-friendly, art-dominated lifestyle. Blake, who was born to the rodeo circuit, finds his artistic inspiration close at hand, in the Western lifestyle he was raised to and the frontier and ranching history that surrounds their Texan home.

- Artist Buckeye Blake

- Buckeye Blake, “Comanche Ranch” | Watercolor | 15 x 13.25 inches

- Buckeye Blake, “Down from the Rimrock” | Watercolor | 12.25 x 16 inches

- Teal Blake, “Penned Watercolor” | 16 x 20 inches

- Father and son Buckeye and Teal Blake

No Comments