11 Mar Dwelling in the Thin Spaces

KATHRYN MAPES TURNER IS STIMULATED BY the boundaries of evanescence. Her elegant work often explores edges found between the physical here-and-now in nature and what shamans reverentially call otherworldly dimensions. Even if we don’t see them, she says, they are there; what we must do is open our minds.

While this may sound New Agey, Turner isn’t that kind of painter. The great Italian Renaissance painters, too, were intrigued by the challenge of translating transcendence through art. The fact that Turner’s imagery makes allusions to wildlife is one of the reasons her work stands apart.

At the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, there’s been a new acquisition added into the permanent collection — a major oil painting by Turner, which did not arrive in the same form that it started. A similar observation could be applied to the artist herself.

Three Matriarchs is an ethereal, almost haunting portrayal of a band of elk mothers sleeking through the Snake River’s misty, twisting flanks at dawn. For Turner, having it join masterpieces by both famous deceased artists and living legends generations her senior not only validates her growing stature as a painter of the natural world; it is, in a way, an existential statement about how she approaches allegory.

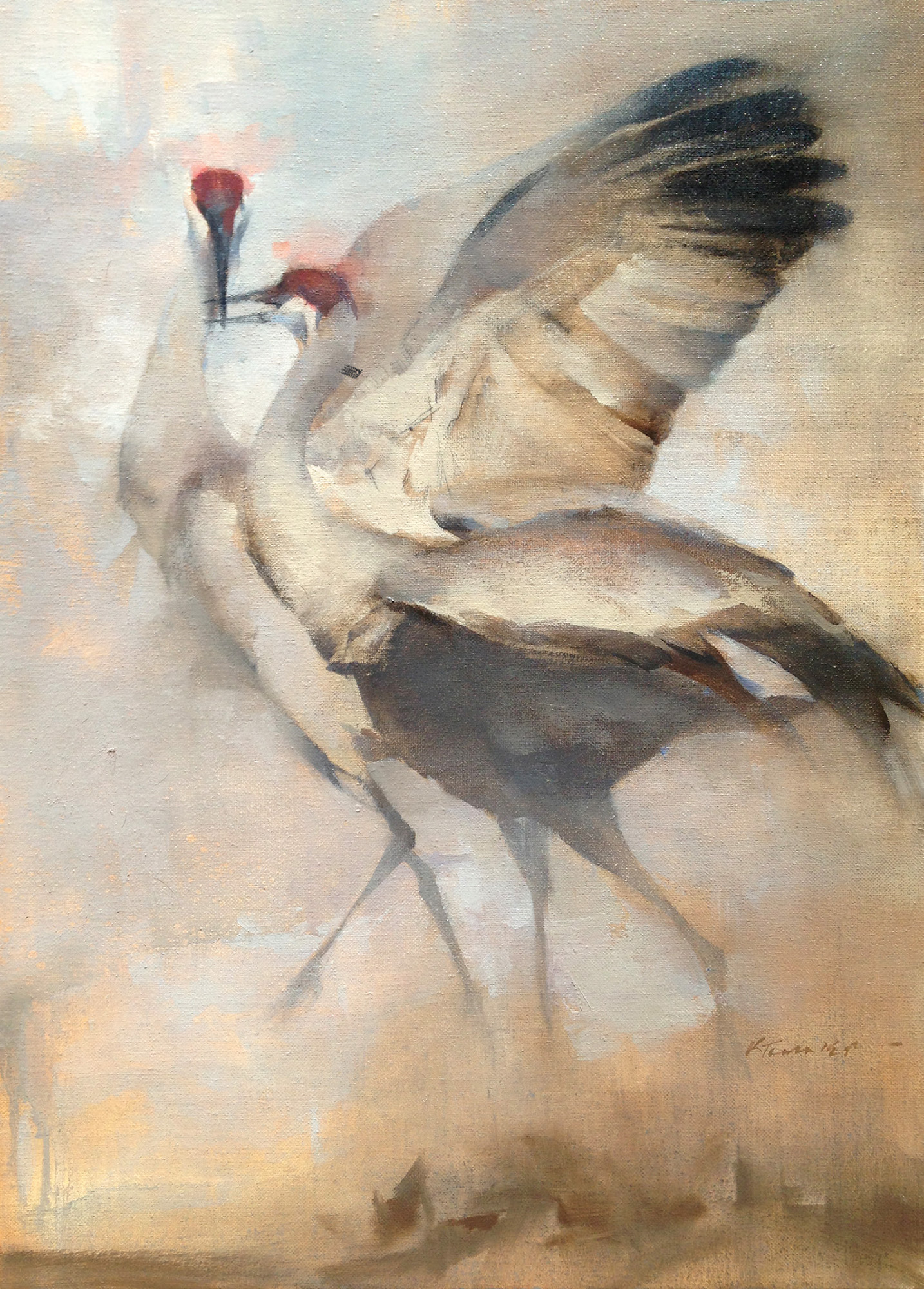

In addition to the prestige of Three Matriarchs being purchased for the National Museum of Wildlife Art, Turner recently had a portrayal of sandhill cranes acquired by the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, where she’s been juried into its annual Birds in Art exhibition, and other pieces have won top honors from the American Impressionist Society.

Painter John Felsing, a mentor to Turner for much of the past decade, and who is celebrated for his own atmospheric compositions, shares this observation about her ascent as one of the best impressionists of her generation.

“As an artist, you can either reproduce what’s readily visible and call it adequate. Or you can make things visible that aren’t — things that have as much to do with what dwells inside of us as the forces of life that every once in a while reveal their presence through the metaphorical fog,” he says. “Kathryn isn’t painting nature. She’s becoming nature.”

A daughter of the Northern Rockies, Turner was born in 1971 and spent much of her childhood in Jackson Hole on horseback being a cowgirl. Her family still operates the landmark Triangle X Guest Ranch in Grand Teton National Park, and as a kid she awoke every morning to the imposing loom of the Tetons. Growing up, she knew the late John Clymer [1907–1989] and Conrad Schwiering [1916–1986], who became renowned as “the painter of the Tetons.”

Turner’s uncle and cousins still run a hunting outfitting and guiding business on the adjacent national forest. Her father, John F. Turner, trained to become a field biologist, then went on to become president of the Wyoming Senate and later served in the administrations of both Presidents George Herbert Walker Bush and his son, George W. Bush. For the former, her father was national director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and it was that tenure that brought Kathryn to Washington, D.C.

“It’s the same old story. In order to fully appreciate the West,” Turner says, “you have to leave it for a while. But I didn’t go willingly.”

In the nation’s capital, she attended high school and, thanks in large part to Ann Simpson, wife of former U.S. Senator Alan K. Simpson of Wyoming, Turner received a crash course in art history, walking the halls of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian’s National Gallery of Art and savoring historic nature dioramas at the National Museum of Natural History.

After prep school, she majored in studio arts at the University of Notre Dame. On trips home to Jackson Hole, she fell in the company of a remarkable circle of Western landscape, wildlife and studio painters, among them Ned Jacob, Milo “Skip” Whitcomb, T. Allen Lawson, Kathy Wipfler and the late Bob Kuhn [1920–2007], when he visited the valley.

Renowned art collector Bill Kerr remembers meeting the then-teenage “Kathy Turner” in the mid-1980s when she attended an art workshop held at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, which Kerr had co-founded.

“She made quite an impact on me at our first encounter,” Kerr shares, noting that each participant was asked to create a piece. “Kathy produced a watercolor of two mountain goats cast in bronze. It was startlingly good, easily the best of all. Nearly 30 years later, that watercolor holds vivid in memory, and that young lady, who grew up to become Kathryn Turner, the award-winning professional artist, continues to amaze.”

There were few indications in the early years that one day Turner would become known for painting wildlife. “Wildlife has been showing up more in my work. It hasn’t been deliberate. It’s happened from being outside and living where I do,” she says. “I find painting wildlife to be a lot more fulfilling than painting landscape, and it’s made me more determined to ensure we protect the places where animals live.”

Trained in plein air, Turner delved into landscapes and attracted a following for her watercolors and oils. Only after she turned herself loose in the natural world, shedding inhibitions, challenging what she thought she knew, did she come to understand the sentience of mountains, forests, water bodies and the myriad animal lives passing through them. Only then did the distance separating Turner from her subjects begin to close, she says. And only then, observers note, did Turner shift from being primarily a talented observer of pastoral and wild settings to gaining national distinction as an exceptional interpreter of them.

“Part of letting go has been discovering myself and losing myself, adopting a philosophy toward art that is about resisting over-control,” Turner says. “My two greatest teachers have been watercolor, where I started as an artist, which is a very therapeutic medium for a control freak. My other instructor has been nature, and she’s taught me that some of the most beautiful things are the simplest.”

Evidenced by her recent work, she’s poured an enormous amount of time into studying techniques of Japanese and Chinese painters. She also embraces the pagan notion, born millennia ago in the British Isles and later adopted by Celts and Christian mystics, that asserts there’s a “thin place” separating our physical reality from another dimension just beyond our ken. A few summers ago, she explored it as a theme in a sold out, one-woman show, and many of those works featured the Tetons from different angles and moods.

“If you live in Jackson Hole and you are an artist, you don’t have a choice,” Turner says. “You have to address the Tetons in some way.”

Ever dominant, the iconic summits can be both a blessing and a curse. So prominent is the profile they can divert attention away from everywhere else around them. Thomas Moran interpreted them, so did Albert Bierstadt, Carl Rungius and hundreds of others.

“It is really intimidating to paint those mountains because of the reverence I feel for them. Frankly, it takes a lot of nerve to try and paint their beauty,” Turner says, noting that doing them justice means sparing them from trite depiction.

She remembers stories from her grandmother of how old-timers regarded the Tetons before there was a commercial airport and being snowed in was a given in winter. “Those first generations who settled permanently in the valley had a conflicted relationship with the Tetons. They were undeniably beautiful, but they represented a physical barrier to accessing the outer world and, in a way, the Tetons reminded them once the snow started to fly that they were trapped.”

When Turner and I spoke she explained that on the previous morning she’d been out photographing and painting wildlife. At the same time she was cramming information into a study on her portable easel, an avalanche rumbled down a slope, killing a skier. Nurturing as the mountains are to the common identity of Jackson Holeans, and as solemn and benevolent as they might appear, they are indifferent to the whims of people.

There is power and truth, Turner says, in simplicity, distilling the glory of nature down to its basic forms. With fewer barriers, she’s after the paradox of heightened intimacy and occasionally, a glance into the eternal. “Those thin places exist in nature,” Turner says. “We can go there, dwell there, and our souls need such places. I feel like art can provide the same thing in transporting us. I try to make paintings that help us access little windows where revelation can occur.”

How Three Matriarchs, a massive 36- by 60-inch oil, came into being happened this way: Turner had gone on one of her regular outings to the Snake in order to gather reference material — putting together studies for a landscape painting she was thinking of doing featuring the Tetons hovering in the background. “And then three elk emerged seemingly out of nowhere, having been hidden in a low cloudbank,” she explains. “They reminded me that we are not always aware of what resides just beyond the limits of our sensual perception.”

Turner considers it the highest of honors that Three Matriarchs earned a place in the museum’s permanent collection, sharing company with some of the finest wildlife artworks of all time. “The museum has brought me back full circle,” she says.

In 2015, Turner was commissioned by her alma mater, the University of Notre Dame, to return to campus and paint one of its most iconic landmarks, the Golden Dome. Her interpretation is an abstracted version. Over the years, she has painted in Italy, as well as famed edifices around Washington, D.C. Bill and Joffa Kerr own one of Turner’s studies of the Jefferson Memorial. They also proudly have a landscape overlooking Jackson Lake and a floral still life. “Each is different in subject matter, however whichever one you’re looking at brings visual harmony to the viewer,” Bill Kerr says.

In 2016, Turner joined ornithologist George Archibald, considered the leading authority on wild cranes of the world, on a pilgrimage to watch migratory sandhill cranes massing along the Platte River in Nebraska. “Artists who paint the natural world, especially birders, are a funny bunch, but they’re my people,” Turner says.

Felsing explains that Turner’s embracing of wildlife isn’t about documenting animals as subject matter, it’s about sensing how animate objects — spirits, beings, sparks of life — give landscapes a greater depth of presence. “We’ve had many long conversations about the pitfalls of Realism,” Felsing says. “And instead of examining together the works of other wildlife artists, we’ve been looking at Abstract Expressionists Rothko, Diebenkorn, de Kooning and Impressionist Twachtman. Their work demands response in ways that simply painting pretty pictures does not.”

“John has been ruthless in encouraging me to find my voice, pushing me, pushing me hard,” Turner says, adding that he offers critiques of works in progress as they chat via FaceTime. “His big thing is being consciously aware of immediacy, being awake in the moment. It’s the way he approaches his own relationship with nature, but he doesn’t want me to follow his path or anyone else’s. He says the path must be my own.”

Felsing says it’s misleading to describe Turner as simply going through a period of transition from plein air to more ambitious studio painting. “She’s evolving. She’s pressing past her comfort zone into uncharted territory. It’s exhilarating when work reflects the confidence you feel, but it can also be a frightening place to be,” he says. “If you look at the best art that’s ever been created in history, it’s been done by those who were not halted by fear.”

Painter Skip Whitcomb explains that the danger for young painters receiving acclaim in their 20s is that success makes them complacent and risk-averse. “Unlike others who have lost their way, Kathryn is very earnest in her explorations. But I feel that she has just scratched the surface of what she is capable of doing,” Whitcomb says.

“She has a tremendous pool of ability, and by living where she does, she’s absorbed aspects of the natural aesthetic that you can’t learn or teach. Her challenge now is rejecting the path of least resistance even when people tell her they love the work and want her to stop evolving,” he adds. “If we want to reach higher planes of meaning, we all have to probe the dark corners. They are unavoidable. That’s where we really understand who we are and what we are made of. That is the opportunity and the challenge of being alive.”

- “Three Matriarchs” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 60 inches

- “Morning” | Oil on Linen | 10 x 12 inches

- “Teton Sunset” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 60 inches

- “JJ” | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 14 inches

- “Two Step” | Oil on Linen | 30 x 24 inches

No Comments