30 May Back at the Easel

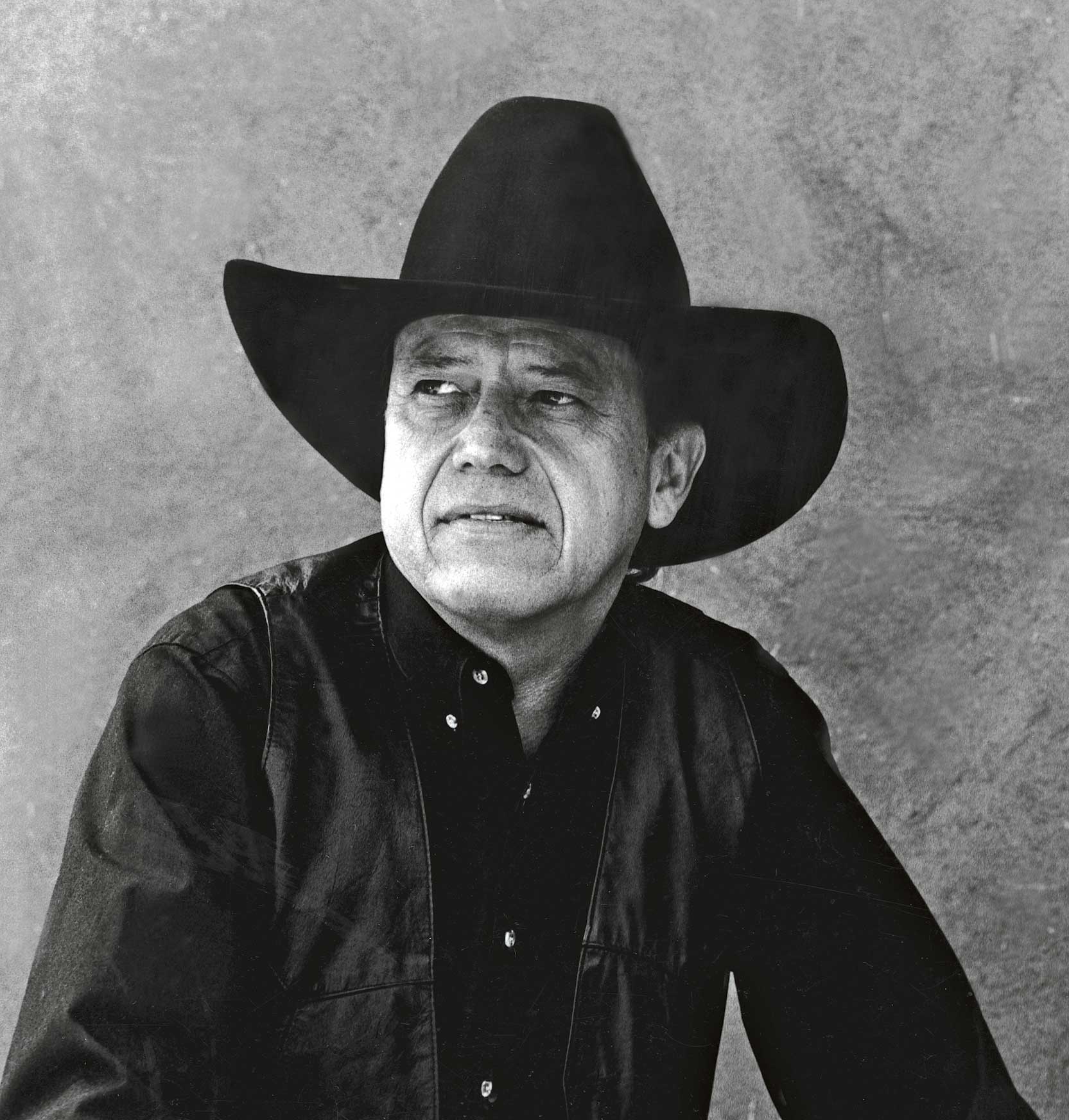

FOR NEARLY THREE WEARY YEARS, JOHN NIETO WANDERED ALONE in the tortured desert of his own mind. Felled by a stroke in October 2002, the acclaimed Spanish/Indian artist, whose instantly recognizable works are collected and prized around the world, suddenly could barely speak. His hands shook uncontrollably. He would fall over when walking and, worst of all, he became so disinterested in art that he gave away all his brushes, paints and easels.

“I was living in a black closet from which I could see no escape, and during those years, the only thing I recall doing that had any meaning, was holding my infant grandchildren,” says Nieto. And yet, on July 7, 2005, in a hospital waiting room, a total stranger briefly and inexplicably touched the Nietos’ lives, after which John was fully restored and asking for brushes and canvases.

“To that point,” says his wife, Renay, “I felt like a widow. After 30 years together, I had despairingly watched my man, my best friend, my lover and my confidante become an empty shell sitting on the couch. Everything was gone. We gave up hope. But without a doubt, an angel touched our lives that day, and gave us a miracle.” But more on that later.

Today, Nieto is back at the easel and is “an extremely prolific artist who has been in very high demand for more than 25 years. He has a style that has been widely imitated, but never equaled,” says Wolfgang Mabry of Ventana Fine Art on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road.

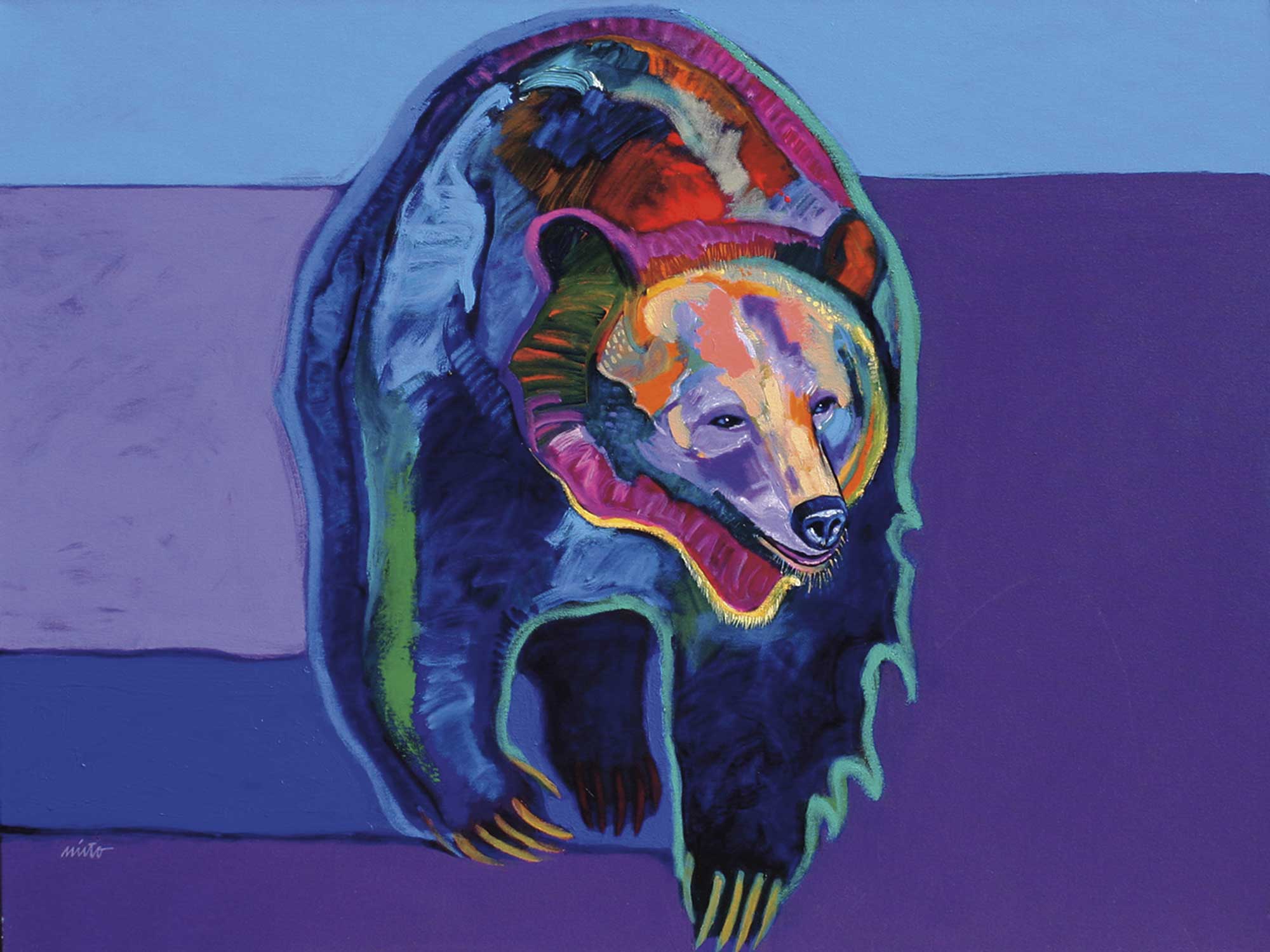

Colors — rich, vibrant and full — are Nieto’s stock in trade. He has a palette that knows no boundaries and he uses it to get across some powerful images. His Grizzly Bear, for example, appears ready to lumber right off the canvas, its huge shoulders rolling under the purple, blue, red, orange and green fur, against a background of lavender, blue and purple. Verbally, it doesn’t make much sense, but visually, it is graphic and powerful.

In a completely different mood, Laguna Beach, which most artists portray as a beautiful, sweeping, surf-lined bay, in Nieto’s world is represented by a single bird, far too colorful to be a seagull, walking on a green, purple, black and lavender beach and casting a bright red shadow. Again, Nieto forces the viewer to take another look.

Gallery owners and avid fans say they see no difference between the work of the old and the new Nieto. Alex Windsor Betts of the Windsor Betts Art Brokerage House in Santa Fe agrees. “He was a trendsetter from the outset, and he has carried on with his bold, imaginative style,” she says.

His vivid colors and French Fauve style still vibrantly portray his centuries-old mestizo family background — a blend of Spanish and American Indian heritage — of which he and his family are extremely proud.

“I don’t expect collectors to see any difference in my work pre- and post-stroke,” says Nieto. “But for me the differences are enormous — maybe not in what I paint, but in how and why I paint it. Before, I was painting my reaction to the world: the Kennedy assassination, the pill, rock ’n’ roll, the bomb — I was busy being important and going to meetings and getting to be known by people.

“But I have been given a new chance in life. I have been born again, not in the religious sense, but in the sense that I have been given a new opportunity to properly practice the gift of my art. I am the steward of what I can do, because there was so much time in which I could do nothing. Before, when I felt it was time for a piece to be finished, it was finished. Today, I don’t mind repainting a face 10 times over if it is not to my liking. I used to say that I would never include black in my paintings. Now I never say never to anything. I will use black in my works when it is appropriate. My priorities have been focused down to two things: my family and my art. Period.” However, the artist continues to always wear black clothing: “I prefer to keep the colors for my canvases.”

“Today my painting is more of an exploration inside myself and it is incredibly exciting. Sometimes I will finish a piece and sit looking at it while my wife is calling me in for supper. But I tell her I am very busy right now as I sit there having a conversation with the piece, and since recovering from my stroke, I don’t feel bad about that at all. The painting is a friend, a creation that I like embracing and incorporating into my little world, and I’m not crazy,” he adds with a gentle smile. The conversations, he says, “have become part of the creative process, just like mixing paint and washing brushes.”

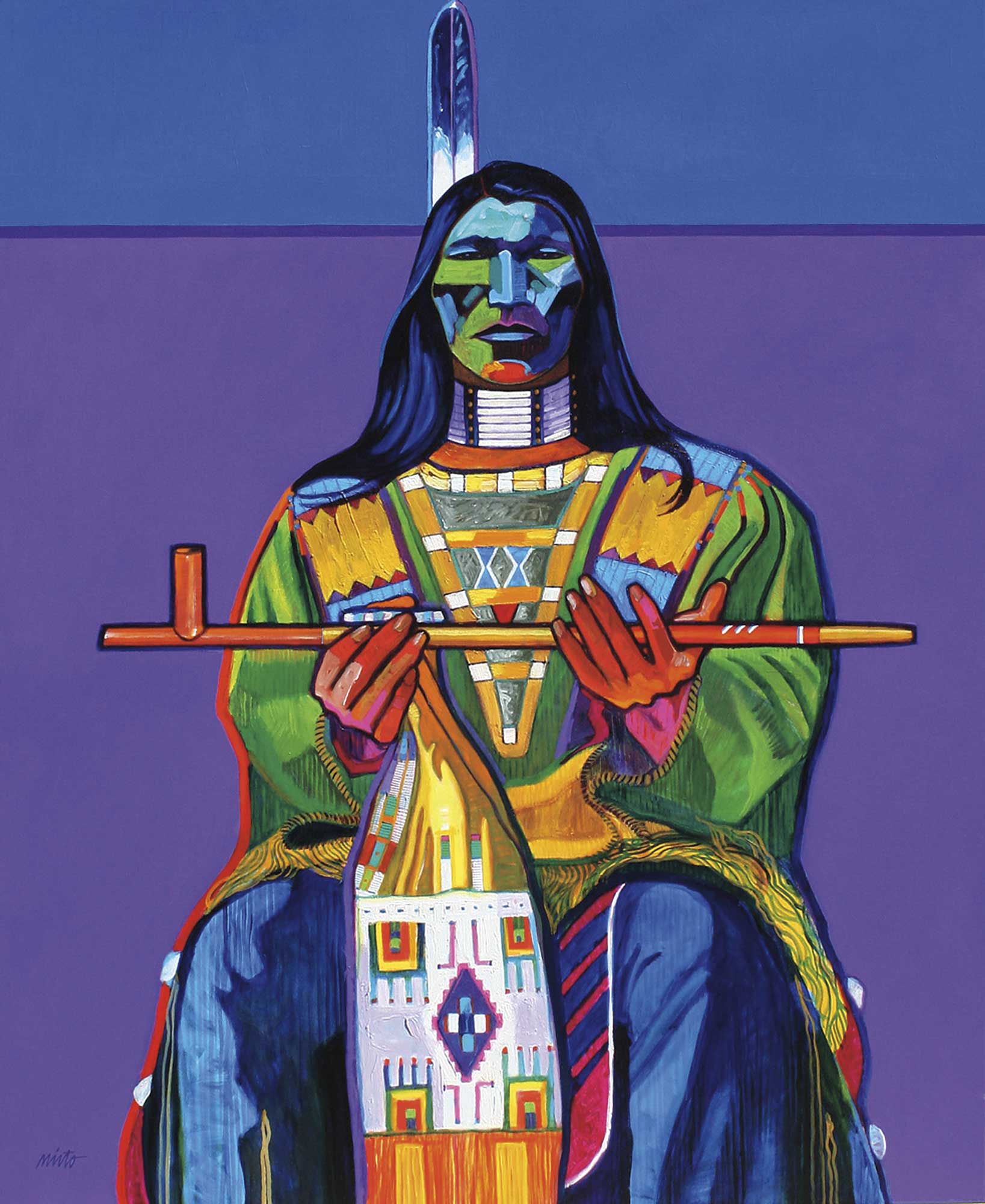

Nieto is particularly well known for multi-colored animals, especially the wolf, the deer, the bison and the bear, with two great examples of his bold and creative use of color being Coyote Self-Portrait and Buffalo at Sunset. And since his grandmother said to him, “John, paint my people,” Nieto has faithfully painted the mystery and the majesty of the Native American people, including the gorgeously colored Peace Pipe, Zuni Olla Bearer and the suitably scary Navajo. Nieto says that he takes an ordinary subject — animal, person, maybe a building — and paints it “as I see it.” But remember, he cautions, “I paint from an emotional attachment with the subject, not a cerebral one.”

Nieto took up the pledge to be an artist while attending kindergarten in Kansas. “We had this great art teacher who dressed us little kids up in smocks, gave us tubs of paint and big brushes and told us to fill all the empty spaces on big pieces of newsprint. I fell in love with the whole process. The smock was so formal; it was a wonderful ritual. It felt so comfortable and natural behind that little easel, and I sometimes think that I’ve made all the important decisions of my life right there.”

But it would be a quarter-century later, when he was making a successful living as a graphic artist and emerging as a fine artist, that Nieto would have what he describes as “probably the pivotal experience of my life.” “I was around 30 years old. I had graduated from Southern Methodist University (majoring in art and art history), spent time in the military and was making a living as a graphic artist. I decided to go to Paris, which I considered to be the art capital of the world, and I intended to live there and become a painter.” At the time, he was doing abstract impressionistic works in the style of Franz Kline.

It was in Paris that, for the first time, Nieto was introduced to the Fauve style of painting: large splashes of color, applied with bold stokes and large brushes loaded with paint. “I’d never seen it before, but I was immediately comfortable. It took me right back to kindergarten with my little smock and tubs of paint and newsprint. It’s like an old buffalo vest I have — as soon as I put it on, I feel comfortable.”

Though the Fauve movement in France lasted 10 years from 1900 to 1910, it only garnered public attention from 1905 to 1907. It was led by Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, and dubbed Fauve — French for “wild beasts” — by the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles in the fall of 1905.

It is the freedom of the Fauve style that attracts Nieto. “You can put down a brush load of paint and say, ‘Oh yeah. That felt soooo good,’ like a good riff in jazz,” says Nieto, who plays the base horn and trumpet.

Born in Denver in 1936, Nieto is the third oldest of 14 children — seven girls and seven boys. His grandfather was blinded by smallpox but taught himself to play the violin, playing at churches and bars for 50 cents a night. “He got into a lot of barroom fights, too, though I don’t know how he handled that while being blind.” Suffering during the Great Depression, his father became a Methodist minister and agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. “He was constantly being reassigned, and in each new community, we, as a family, seemed to be constantly on the outer edge of the local society, which is why all my brothers and sisters are keenly interested in our history.”

Of his mixed Spanish and American Indian heritage, Nieto explains that Spanish men came to New Spain (Mexico), including his own family, in the early 1600s. “They did not bring wives,” says Nieto. “Instead they married Mexican or Pueblo Indian women, which produced the mestizo.”

Acutely conscious of the two cultures that have formed his world, Nieto says, “I feel an emotional leaning toward the Indian and an intellectual leaning toward the Spanish. While painting, the inspiration comes from both sides, though not on a conscious level because I do not analyze what I am thinking; I have no formula for my painting — no idea what it is going to look like when I start. I might know that it is going to be a wolf, but beyond that, all I bring to the canvas is enthusiasm — enthusiasm about creating something from nothing, and doing it from my own point of view.

“In truth, the stroke was good for me. Today I am a better person and a better painter. I paint a lot more. I am not distracted. I have a much better balance in my life.” After the stroke, the Nieto family moved to a small lakeside community east of Dallas, where “I’m sure we will stay,” says Nieto. “It is so quiet and beautiful to look out across the lake.”

As the new millennium dawned, John Nieto was on a roll. His work was selling well, he had done a series for the 2002 Winter Olympics and a piece to commemorate the 9/11 attack on New York City. He had collectors throughout Europe, Australia and the Far East, and for 20 years he had been part of the U.S. Department of State’s Art in Embassies Program in which original pieces by U.S. artists are displayed in U.S. embassies around the world.

But after the stroke hit in October 2002, Nieto fell deeper and deeper into depression, becoming so withdrawn that he spent eight hours a day in therapy. He could not read, and “I looked at my art and wondered why I even bothered doing it. I was totally disinterested.” There were occasional, fleeting moments of lucidity, recalls Renay. “Once, I was having problems with the boys and I said to John in despair, ‘Oh John, I wish I could discuss this with you.’ And he replied clearly, ‘So do I.” I looked up in hope and surprise, but he was already gone again.

But, as he moved into the third year of his depression, more physical problems developed and the doctors feared he was suffering heart problems, possibly congestive heart failure. His condition deteriorated until he was very sick indeed, recalls Renay, to the point that the doctors called him to go into the hospital for an angiogram.

“They told us it would be a three-hour procedure,” says Renay, “but we were still sitting in the waiting room five hours later.”

Son, Anaya, takes up the story. “Mom, two of my friends and myself were sitting there and getting really nervous. Then this little guy came in and sat down. He seemed barely 5 feet tall and real awkward, and he kept leaning forward and looking at us. Finally he came over and said we looked worried, and I said that my dad was in surgery and it was taking much longer than expected. He said, ‘Oh. I’ll go check on things,’ and walked right into the room where they had taken Dad. He came out a little later, put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Don’t worry, everything will be just fine.’ He turned, and walked out the door to the street.”

Renay continues. “The doctors came out and said they were baffled. The tests had been wrong and there was nothing wrong with John’s heart. We asked about the little man who checked on John and they laughed, saying that nobody could have gotten through the door we indicated. It was absolutely impossible. And we found that nobody else in the waiting room had seen the man either. But we definitely did.”

John was put to bed and the next morning, awakened “completely cured,” says Renay. “Every stroke symptom was gone — voice steady, hands steady, walk steady and a thirst for painting. He called for paints and brushes and did four paintings immediately from photographs, and completed 16 works with virtually no breaks.”

Renay leans forward, her hand clenched, her voice tense. “Believe us,” she says with passion, “There are angels out there.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Nieto is represented by Ventana Fine Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Mountain Trails Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. He currently has a one-man show at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, just outside Atlanta, through May 24. He also has an annual show at Mountain Trails in July and at Ventana Fine Art in August.

For almost 50 years, Michael Scott-Blair has been a writer and photographer for newspapers and magazines in England, New Zealand and the United States, and was twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. Most recently he was senior writer for Wildlife Art magazine.

- “Grizzly Bear” | 2006 | Acrylic | 30 x 40 inches

- “Navajo” | 2006 | Acrylic | 20 x 30 inches

- “Peace Through the Olympic Games” | 2006 | Acrylic | 60 x 48 inches

- John Nieto

No Comments