30 May Camp Run-a-muk

RICHARD AND MARDI BRAYTON HAD BEEN LONGTIME VISITORS TO INVERNESS, a tiny costal hamlet in northern California, before they purchased land there. And they owned their property for several years before they considered doing anything to alter it. What drew them to the area was its unspoiled natural wonders, its feeling of timelessness and its sense of community. When it came time to build, then, they knew that the way to proceed was slowly and thoughtfully. Had they rushed in, they might have built one large cover-all-the-bases structure. Instead they did the opposite — and the result is magical.

Inverness, a community of 1,400 perched on the wildlife-rich shores of Tomales Bay, has been a summer retreat for San Franciscans as far back as the 1890s. Today the town remains much as it was then: It boasts two cafes, a couple of inns, a marina and an understated yacht club stretched along the winding road that hugs the bay. Situated on the leeward side of Point Reyes National Seashore, its structures are scattered over a steep hillside that looks across the shimmering waters of the bay to the open, rolling hills of rural Marin.

Richard Brayton, a prominent San Francisco architect, and Mardi Brayton, an artist and filmmaker, bought their property in 2000. The parcel, which gives a bird’s eye perspective over Tomales Bay, comprised only two-thirds of an acre, yet “felt huge by virtue of the view,” explains Richard. Although it came with a tiny A-frame structure — which in true 1960s back-to-the-land style had been built from a kit — one sleeping loft would not accommodate their family of four, nor their frequent guests.

In keeping with the low-key vibe of the community, and the desire to stay tuned to nature, “We knew from the outset that we wanted to have a camp, a community of buildings,” explains Richard. “Then it became clear, because of the size of the lot and septic considerations, that that’s what we had to do.”

The A-frame, called The Lodge, remains true to character, with its small sleeping loft and galley kitchen. The vintage woodburning stove with its conical fire hood still evokes the peace-and-love period. “Carpet and paint,” comments Mardi Brayton. “That’s about all we did.”

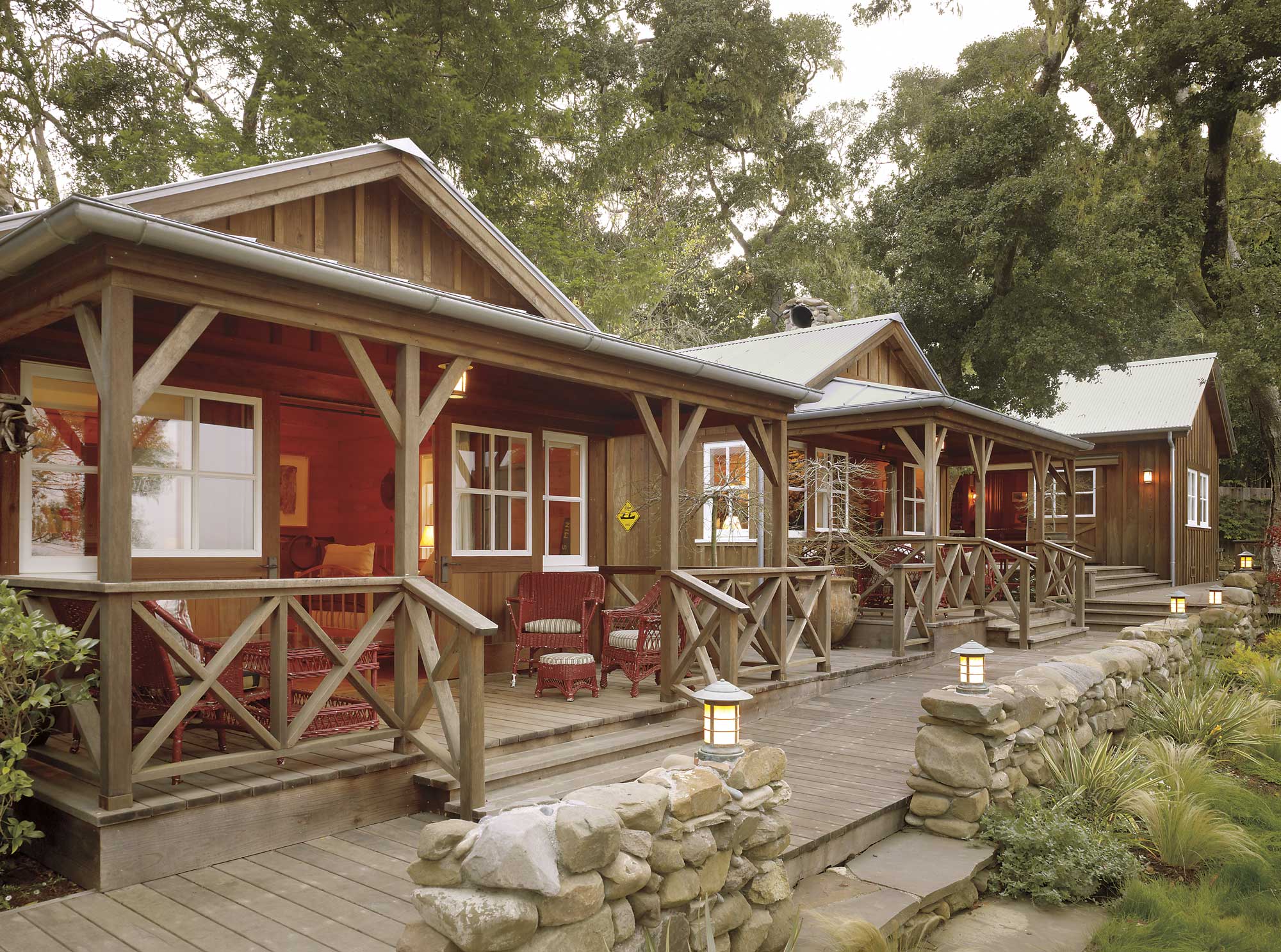

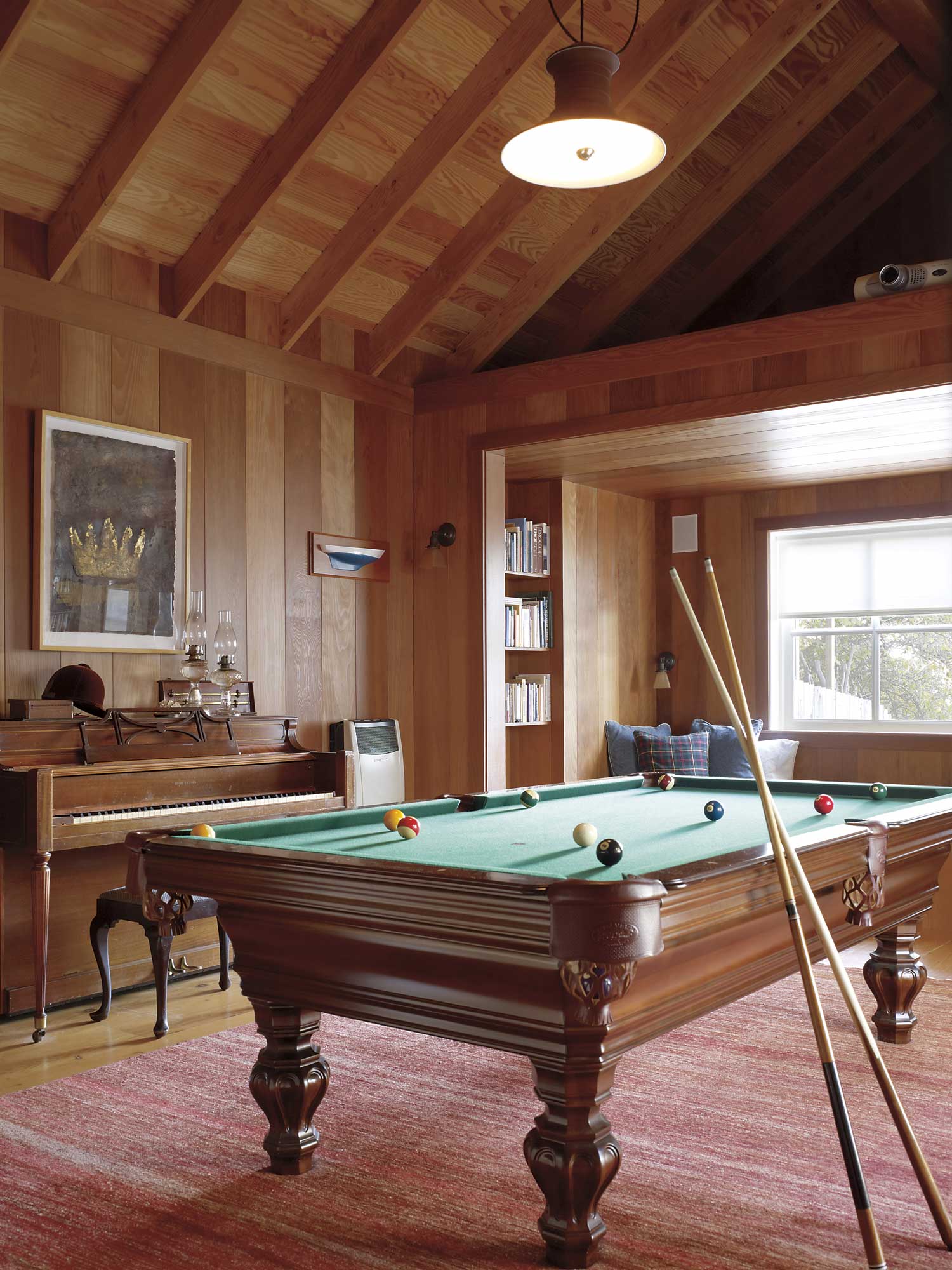

For lodging, Richard Brayton designed two sleeping cabins, board-and-batten structures with natural rock fireplaces, corrugated tin roofs and covered decks with copper lanterns. The tone inside these cozy spaces is set by oversized fireplaces, comfortable beds, rustic objects, pencil drawings done by Richard’s father, Mardi’s paintings, British campaign chairs, Western artifacts and flooring made of old wood from a tobacco farm back East. Next was the Bunkhouse, a cabin with redwood walls and sliding barnlike doors furnished with a billiards table, built-in couches, bookshelves and an upright piano. Says Richard, “It’s really just a place for the kids to play pool, play music and probably do some drinking that we don’t know about.”

The concept of multiple structures, explains Richard, “centers on the idea of a rustic camp comprised of a collection of cabins connected by boardwalks, each of which provides a single function, such as eating or sleeping. The boardwalks knit everything together and make it feel almost like a little village.”

The separate cabins also allowed the Braytons to build around, and thus preserve, the property’s heritage oaks. The boardwalks, reminiscent of Fire Island’s iconic Point of Woods community, where the Braytons have spent time, provide a visual link between the structures while framing a natural lawn of meadow grass with a dramatic outlook over the Bay. The boardwalks are edged by low walls of local rock; at night, copper lanterns light the way under the stars. Multiple decks, sliding doors and outdoor cooking areas create a strong connection to the outdoors, while an antique canoe, vintage pick-up truck, hammock, rock circle and memorabilia bestowed by friends and family lend the place a timeless, woodsy feel.

Perched literally on the edge of the hillside is Mardi Brayton’s art studio. Consisting of one large room for art-making and display, it opens fully to the natural world through large sliding doors. Clearly this is an artist both immersed in and inspired by nature. A bundle of distinctively shaped driftwood pieces dangles from one ceiling; groupings of dried plants collected on her rambles hang against a plain white wall. There are dried mushrooms and mosses and prayer flags and, tacked up on a wall, “The Red Wheelbarrow,” a poem by William Carlos Williams. The steps on the ladder to the loft have been turned into bookshelves for stacks of art books. Her corner desk and window take advantage of the view while leaving as much wall space as possible.

The artist says that living a nature-intensive life at Point Reyes National Seashore has had a pronounced effect on her work. “I do collages, I draw, but more and more my work is becoming more sculptural,” says Brayton. “I always had a studio in the city, and the work was more chaotic in feel, and full of action. Now, here, everything has changed. There’s a fear about losing nature, and a worry about nature. I like my work to raise awareness about issues like endangered species. I’ve started collecting materials about bees. I’m now working on medicinal plants. My show at Point Reyes last summer was specifically meant to educate about what’s growing in our backyard. I’ve been doing a study on lichens, too.”

Brayton says she now finds herself in the unusual position of sometimes commuting from the city out to the country to work in her studio. “It’s my little inner sanctum,” she says. “I don’t know how I would live without it.”

When the Braytons need inspiration for their design work, they might hop into one of their small boats and motor, canoe, sail or kayak over to Nick’s Cove. They might go fishing or birdwatching. Or they might take a quick half-hour hike up to the top of Mount Vision. From the overlook at 1,200 feet, they can take in panoramic views of ocean, meadows, Drakes Bay Estero, Marin hills and the whole of Point Reyes. But whatever the weather, however adventurous the outing, at the end of the day they know that their refuge awaits.

Chase Reynolds Ewald writes from her home in northern California. Her latest book, The New Western Home, was recently released by Gibbs Smith, Publisher.

- Two cozy board-and-batten sleeping cabins are central to Richard Brayton’s concept of a “community of buildings” connected by boardwalks.

- Multiple dwellings create a camplike atmosphere and protect the property’s heritage oaks while forcing the residents outside into the weather or under the stars.

- Mardi Brayton’s art studio is nestled in the trees, with plenty of natural light and big views over the bay from her corner desk. Its one large wall is hung with driftwood, dried plants, foliage and other items she finds on her long walks, from which she finds abundant artistic inspiration. Her work has been so influenced by Tomales Bay, she says, that she sometimes finds herself commuting from San Francisco to work.

- Inverness, a tiny hamlet perched on the edge of Tomales Bay, sits very lightly on the land. Architect Richard Brayton and his wife, artist Mardi Brayton, built their contemporary camp on a steep hillside with sweeping views of Tomales Bay, with its oyster farms and abundant bird life, and the rolling hills of rural Marin County.

No Comments