09 Jan Reflections of the New West

An exhibition at the Steamboat Art Museum in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, traces the beginnings of “New Western Art” to Lloyd Kiva New and the early instructors at the Institute of American Indian Arts.

Fairland, Oklahoma, was a small railroad town where one could watch trains from the Missouri, Oklahoma and Gulf Railway Company meander through the 225 acres that some 500 people from all walks of life called home. In 1916, this community — located in the furthest reaches of northeastern Oklahoma on the Cherokee Nation — also became the birthplace of Lloyd Kiva New, the youngest of 10 children born to a Cherokee mother and Scots-Irish father.

Doug Hyde, Evening Star | Bronze | 21.25 x 9 x 8 inches

New eventually headed north and attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied fashion. After teaching at the Phoenix Indian School in Arizona and then enlisting in the military, he conceived a grand vision for an experimental school, a “design laboratory,” that would train Native American artists across all disciplines.

In 1962, that vision became the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), located in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a place where young Native American students would be taught to make a living through diverse art forms, from painting and sculpture to ceramics, jewelry making, and more. First operating as a high school and then a university, IAIA took up where the Santa Fe Indian School left off, and New was the proud co-founder along with Dr. George Boyce.

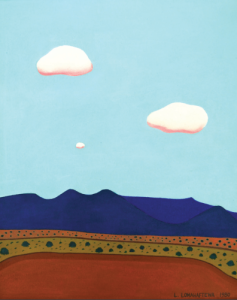

Linda Lomahaftewa, New Mexico Landscape | Acrylic on Canvas | 14.75 x 12 inches | Courtesy of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

“New wrote a manifesto, a proposal, and sent it to the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” says painter Tony Abeyta (Diné), who graduated from IAIA. “There’s a scene in ‘Citizen Kane’ where Charles Foster Kane takes all the great writers from all the other newspapers and has them come work for him. Well, that’s exactly what New did. He said, ‘Allan Houser, you come teach sculpture. Fritz Scholder, come teach painting. Charles Loloma, teach jewelry. He enlisted the best Native instructors in dance and theater as well because he wanted this school to be a multidisciplinary creative center for Indian art. And since New was a fashion designer, he was well-schooled in Modernism. So, the school was progressive from day one.”

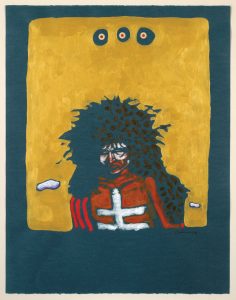

T.C. Cannon, Mandan Warrior | Acrylic on Paper | 26 x 20 inches | 1975 | Estate of T.C. Cannon | Courtesy of Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM | James Hart Photography

The exhibition, ongoing through April 15, is titled The New West: The Rise of Contemporary Indigenous and Western Art. It posits that New’s vision also produced the beginnings of the artistic style referred to as New Western Art. It’s a genre of its own, not to be confused with the Western tradition that originated in the works of 19th-century artists such as Frederic Remington and Charles Russell. Curated by the Booth Western Art Museum’s Executive Director Seth Hopkins, the exhibition was created to redefine how we view and understand contemporary Western art and to recognize New, the faculty he recruited, and the students who followed his singular vision.

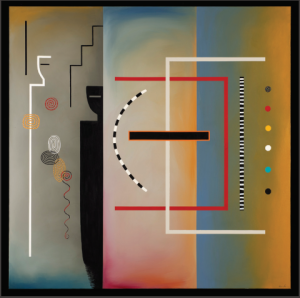

Dan Namingha, Symbols of Hopi | Acrylic on Canvas | 72 x 72 inches | 2001 | Courtesy of Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM | James Hart Photography

The exhibition includes work by more than 25 artists, beginning with pieces by some of the early IAIA instructors, most notably Scholder and Houser. It expands to include works by some of their most celebrated students, such as T.C. Cannon, Earl Biss, R.C. Gorman, Kevin Red Star, Dan Namingha, and John Nieto. Joining this group of early Native American visionaries are contemporary artists currently working in innovative and boundary-breaking styles, including Doug Hyde, Tony Abeyta, Tammy Garcia, Shonto Begay, Kim Wiggins, Billy Schenck, Duke Beardsley, Howard Post, Ed Mell, Logan Maxwell Hagege, Donna Howell-Sickles, and Maeve Eichelberger.

In his introduction to the exhibit catalogue, Hopkins finds inspiration in a quote from Suzanne Deats, co-author of the book NDN Art: Contemporary Native American Art, who writes: “Contemporary Native American art began at a specific time and place. The time was the 1960s when social change was rocking the world. The place was IAIA in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where a few major talents upset the status quo, blew the doors off the curio shop, and buried the Noble Savage forever.”

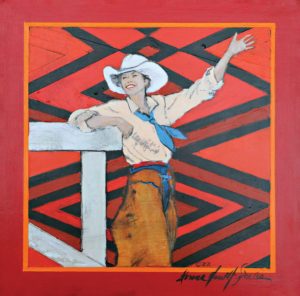

Donna Howell-Sickles, Counting Cows | Acrylic on Canvas | 8 x 8 inches

As Hopkins began researching this concept, he saw that these early IAIA students were expressing ideas and sentiments about the West in wholly original and innovative ways that would come to inspire artists for the next 60 years.

“I spoke with Kevin Red Star, and he said in those early days they were taught how to paint but not what to paint,” says Hopkins. “And they looked to New York City, to artists such as Rothko, Rauschenberg, and Motherwell instead of Remington and Russell. Soon, collectors started seeing this new imagery coming out as well, and the social and political commentary that came along with it, and that opened the door for a much wider and bigger Western art field. The tent is big enough to hold everything that is Western, and Western art doesn’t have to be confined to traditional Realism.”

Earl Biss, Pausing as the Winter Sky Pours Out Its Welcome | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches | 1989 | Courtesy of Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM | James Hart Photography

One of the artists in the exhibition is Ed Mell, who grew up in Arizona and graduated from The ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles in the late 1960s. Upon graduation, he immediately took a job as an art director for a prominent New York City advertising firm. However, in 1971, Mell was contacted by his close friend John Cordalis and was asked to spend the summer teaching art to children at the Hotevilla/Bacavi Community School on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. For Mell, a day spent teaching would be followed by evenings spent walking amongst the hidden canyons and mesas, and those moments inspired what would become his painting career.

While the painters working today look to what artists like Mell, Schenck, and Post were doing in the 1970s, Mell says he and his contemporaries looked to Scholder and the experimental style he began in those early days of the IAIA.

Billy Schenck, Lonesome Dove | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 30 inches | 2020

“Fritz was one of the first guys to not just break the boundaries but be successful at it,” says Mell. “And we all looked to him. What Fritz showed us was that Western art no longer had to be just Realism. The romantic ideal that everyone was thinking about could be given a new spin. For me, I was inspired by those sunsets, but I didn’t want them to be romantic or syrupy. I wanted to show the strength, power, and design of the natural world but still use the beautiful colors I saw out in [Arizona] that summer. Maynard Dixon, of course, touched on all of this earlier too, but I wanted to push things further, more in line with abstraction and a Modern approach. I spent two summers out there, and it changed my life for good.”

Thus, The New West exhibit can be subdivided into three categories of artists: the early innovators such as Scholder, Cannon, Biss, Houser, and Red Star; the artists who took their lead and created new narratives outside the traditional and more romanticized visions of the West, such as Mell, Post, and Schenck; and then the artists who have joined them in this pursuit over the last 10 to 25 years, including Hagege, Beardsley, Wiggins, and Eichelberger. The artists in this third group are fluent in the vernacular of contemporary art and design while also crediting those who came before them for breaking tradition. Works by these contemporary artists are also available for purchase during the exhibition.

Allan Houser, Thinking of Him | Alabaster | 19 x 20 x 14 inches | 1980 | Courtesy of Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM | James Hart Photography

“A modern take on the West is nothing new,” says Hagege, one of today’s most successful Western painters. “Many artists that I’m inspired by were interpreting the West in a sophisticated manner 100-plus years ago. Artists such as Ernest Blumenschein, Buck Dunton, Maynard Dixon, and Georgia O’Keeffe brought their individualistic visions to the subject of the West and opened doors for artists like me. Standing on the shoulders of many great artists that came before myself, I am doing the best I can to see the West through my own artistic vision.”

A similar exhibition highlighting works from the Booth Western Art Museum’s collection was held at the Briscoe Museum in San Antonio, Texas, several years ago. The Steamboat exhibition is drawn largely from the expansive and comprehensive Tia Collection, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and several prominent private collections. The inclusiveness of the exhibition is an example of the more accepting and broad definition of Western art happening today. Traditional Western art shows, including the Masters of the American West at the Autry Museum in Los Angeles, have made a point to encourage and include a more diverse selection of artists from across the entire Western genre, including Native American artists, artists of color, and women.

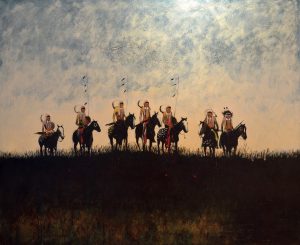

Kevin Red Star, Chief Wild Cat’s Raiding Party | Oil | 16 x 72 inches | 2002 | Courtesy of Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM | James Hart Photography

The West, after all, is a physical space. It’s bound by the canyons, vistas, mesas, mountains, rivers, streams, and well-worn paths that define the region. And the art that flows from it is only defined by the fact that it was created in this particular place as well, be it Santa Fe, New Mexico; Tucson, Arizona; Bozeman, Montana; Jackson Hole, Wyoming; or San Antonio, Texas. It only makes sense that all the people living and working in these places are given a seat at the table and brought into this ever-expanding and ever-inclusive genre.

No Comments