12 Jul Perspective: The Power of a Picture

In 1948, a young photographer named Gordon Parks spent weeks getting to know and aiming his camera at the gritty world of 17-year-old Leonard “Red” Jackson on the streets of New York City. The photo essay that resulted, “Harlem Gang Leader,” was published in Life magazine and led Parks to become Life’s first African American staff photographer. The striking images reinforced the Kansas native’s growing reputation as a professional photographer of immense and noteworthy talent, adding to his work in the fields of portrait, fashion, and documentary photography. But the published piece was not quite as Parks had envisioned it.

Self-Portrait, 1941 | Gelatin Silver Print | 20 x 16 inches | Private Collection

Of the hundreds of photos Parks took of Jackson and his world, the editors at Life selected primarily those that focused on violence, truancy, and death, often cropping them to produce an even more dramatic effect. What was not included were photos that would tell a more nuanced story of the challenges and conditions contributing to gang life. The narrative Parks intended would have offered a more humanizing view, rather than adding to existing cultural stereotypes of young black men. As Philip Brookman, consulting curator for the Department of Photographs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., explains, “Parks made it his work to break down the stereotypes to reveal the underlying problems. The editors at Life didn’t really understand that.”

The breadth and acuity of vision that Parks brought to his creative work, in particular during the first decade of his career as a professional photographer, is highlighted in a major traveling exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Art in collaboration with the Gordon Parks Foundation. Curated by Brookman, Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940-1950 opens September 14 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, and continues through December 29. The show’s final destination is the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, February 1 through April 26, 2020.

Pittsburgh, Pa. The Cooper’s Plant at the Penola, Inc. Grease Plant, where Large Drums and Containers are Reconditioned, March 1944 | Gelatin Silver Print on Board with Typed Caption 9.4375 x 7.5 inches | Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

“Parks was showing the African American experience in mid-century,” notes John Rohrbach, senior curator of photographs at the Amon Carter Museum. “But he was also a uniter, able to work across racial, economic, and class divisions, and photograph all kinds of people from all walks of life. In today’s broad political climate, where we’re struggling with cultural and racial division, this is a good time to be presenting this exhibition.”

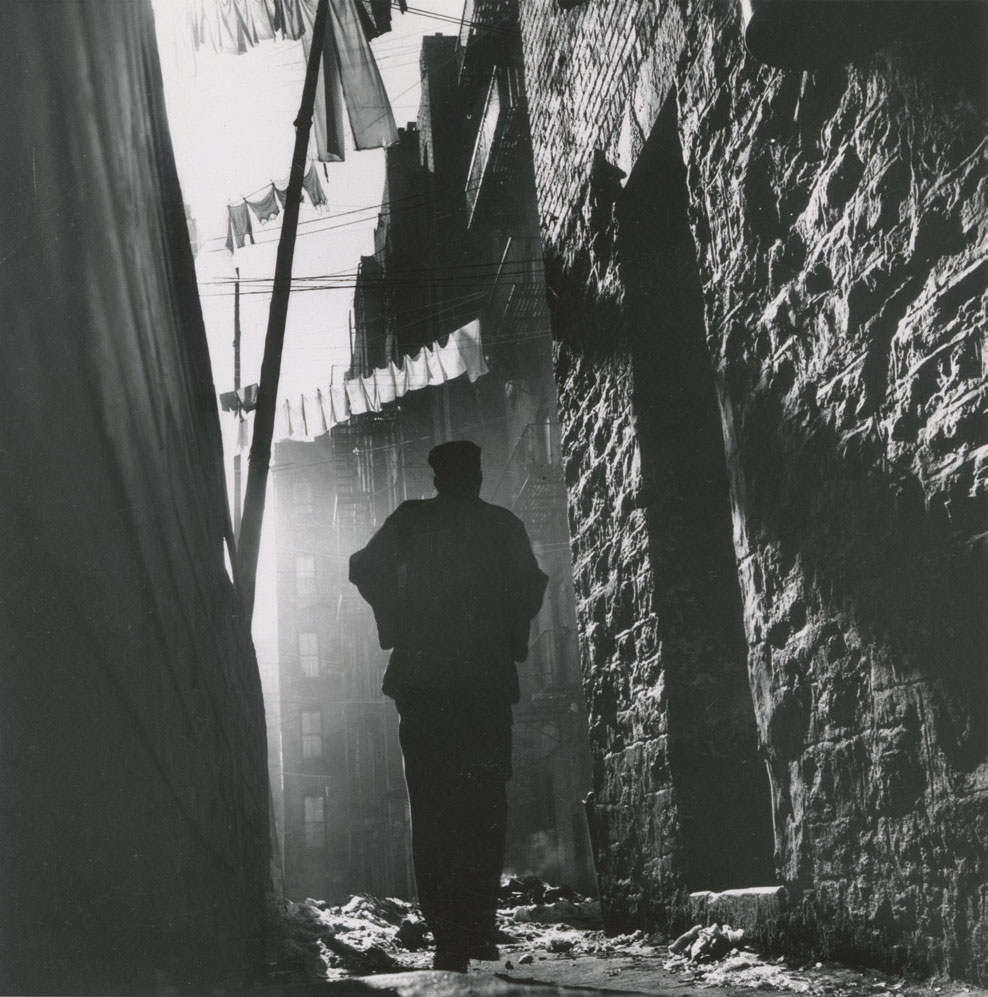

Off on My Own, Harlem, New York, 1948 | Gelatin Silver Print | 4.625 x 4.625 inches | The Gordon Parks Foundation Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks was born on November 30, 1912, in Fort Scott, Kansas, a segregated community whose farms, railroad, and nearby river encouraged his boyhood sense of being part of the country’s expansive mood. He rode horses, loved music, and at age 6 taught himself to play an old upright piano his mother rented. At the same time, he lived in fear and witnessed countless acts of prejudice and racial violence, including the deaths of childhood friends.

The youngest of 15 children (five by his father’s first wife, who died young), Gordon attended an integrated high school, but only because his hometown could not afford two secondary schools. The African American students were strongly discouraged from pursuing higher education and were not allowed to take part in social or athletic activities with white students. When Gordon was 15 his mother died, and shortly afterward he was sent to St. Paul, Minnesota, to live with his sister and her husband.

Within a year, conflicts with his brother-in-law forced him out of his sister’s house, and he found himself homeless in winter. Staying warm at night by riding streetcars between Minneapolis and St. Paul, he attended high school and took weekend jobs washing dishes and mopping floors before landing a job playing piano for $2 a night at a brothel.

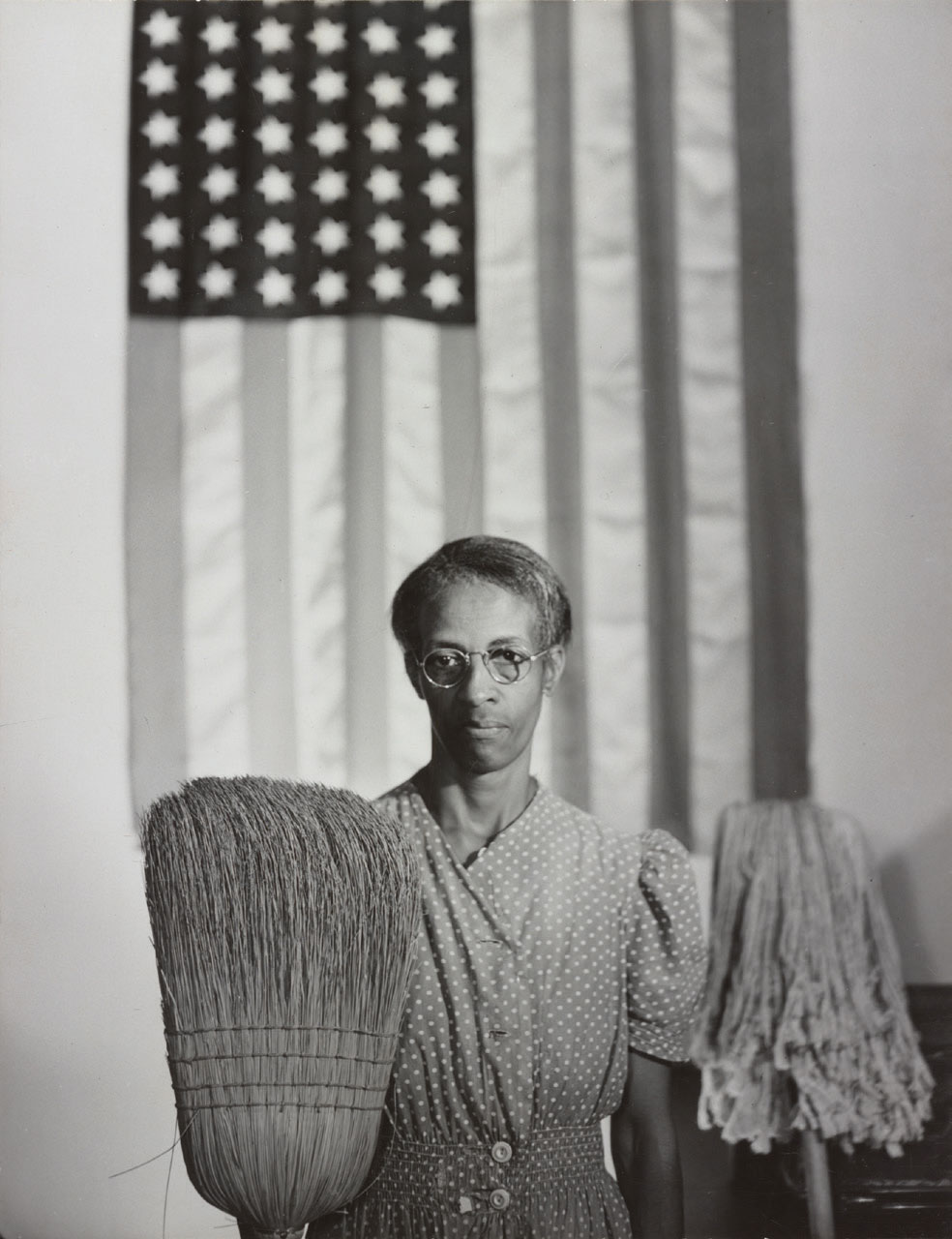

Washington, D.C. Government Charwoman July 1942 | Gelatin Silver Print Mounted to Board with Typewritten Caption | 9.3125 x 7.1875 inches Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph

His first close-up look at the affluent side of life came when he was hired as a bellboy at an exclusive gentleman’s club. The job also allowed him to read newspapers and books in the club library while on breaks. Reading in the club was a testament to his innate drive, curiosity, and desire to learn; by 19, exhausted and having quit and returned to high school a few times, he dropped out of school for good.

For a time, Parks attempted to pursue his first passion of music. He played piano, sang, and composed tunes, performing with various jazz musicians, but a musical career never materialized. Then, in 1936, he took a job that would change his life. He was hired as a dining car waiter on the Northern Pacific Railway’s passenger route between Chicago and Seattle. One day in 1937, a fellow waiter gave him a copy of a magazine. Looking through it, Parks found himself mesmerized by photographs of migrant workers displaced by the Dust Bowl. For the first time, he was intensely aware of the ability images had to evoke emotion by conveying, with intimacy and immediacy, the lives of others.

Soon, another experience helped reinforce this understanding. On a train stopover in Chicago, he made his first visit to the Art Institute of Chicago. As he stood before some of the world’s greatest artworks, he became even more convinced of the power of pictures. Not long afterward, he bought a Voigtländer Brilliant camera at a Seattle pawnshop and taught himself to use it. In every photographic genre in which he engaged over the next nearly 70 years, he exhibited an innate ability for capturing the essence and relevance of his subjects and learning from those with whom he worked. Shooting first for an African American newspaper in St. Paul and later for publications including Ebony, Life, and Glamour, as well as his own portrait photo business and for government agencies, he produced images of such figures as Eleanor Roosevelt, Marian Anderson, Duke Ellington, Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and Muhammad Ali.

Anacostia, D.C. Frederick Douglass Housing Project: Mother Watching Her Children as She Prepares the Evening Meal, July 1942 | Gelatin Silver Print | 10 x 8 inches | Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, 013377-C. | Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

In 1942, Parks was the first photographer awarded the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and was hired for a photography project by the federal government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) under the mentorship of Roy Stryker. It was during this period that he created one of his most well-known photographs, Washington, D.C. Government Charwoman July 1942, a portrait of government office cleaner Ella Watson standing solemnly with an upright broom and mop in front of an American flag. Also called American Gothic, the photo echoes the famed 1930 Grant Wood painting of the same title. Both images reflect the stoicism and quiet dignity of individuals portrayed with the tools of their labor.

Drug Store “Cowboys.” Black Diamond, Alberta, Canada, September 1945 | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.5 x 12.875 inches | National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection) | Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

When the FSA disbanded, Parks worked for the Office of War Information where, among other subjects, he photographed an all-black unit of fighter pilots. Later, came more than 20 years working for Life (on staff until 1961 and then freelancing until 1970), during which time he also explored other creative outlets. In 1969, he wrote and directed a film adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree, co-writing the film’s score as well. The film made him the first African American to direct a major Hollywood movie. It was followed by “Shaft” in 1971 and a Shaft sequel in 1972, helping to open doors and inspire other African American filmmakers, including Spike Lee and John Singleton.

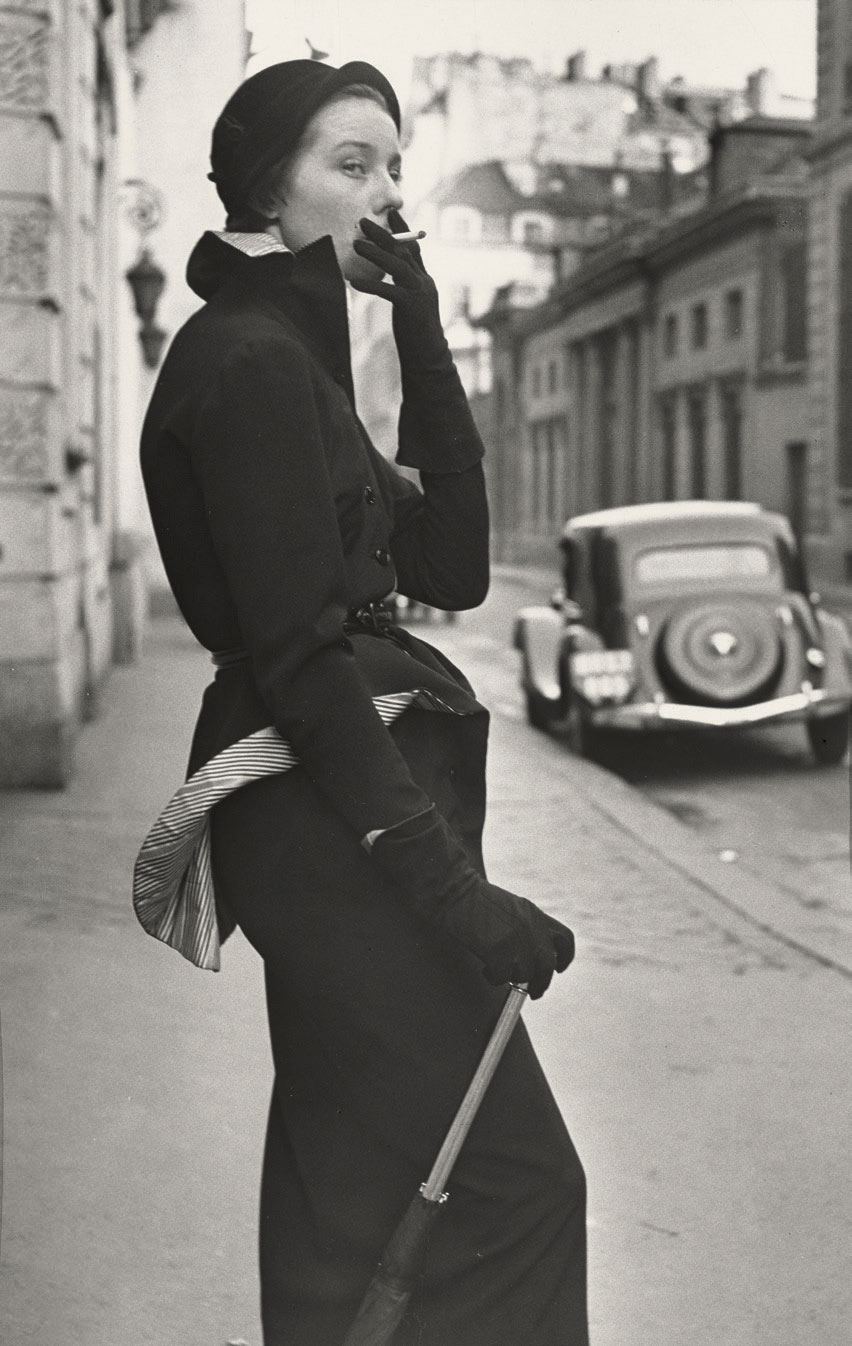

Paris Fashions, 1949 | Gelatin Silver Print | 11.625 x 7.75 inches National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection) Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Crude Oil, Fuel Oil, Gas Oil, Range Oil and Gasoline Pipelines Leading from the Waterfront to the Everett Refinery. Everett, Massachusetts, May 1944 | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.125 x 7.5 inches Standard Oil (New Jersey) Collection, Photographic Archives, University of Louisville | Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Although his photography is seen as significant in its depictions of poverty, injustice, and segregation — conditions leading to the Civil Rights Movement — Parks had a larger goal in mind. Images like Mother Watching Her Children as She Prepares the Evening Meal, taken at a Washington, D.C., housing project in 1942, represented African Americans in ways to which anyone could relate — in this case, a woman preparing food at the kitchen table and watching out the window as her two young daughters play in the yard. It is among the favorites of Amon Carter curator Rohrbach. “It’s about raising kids, raising a family. It’s such a universal image,” Rohrbach says. “And it’s beautifully crafted.”

Such was the case throughout his career. From elegant fashion images of African American women to portraits of individuals and glimpses of daily life, Parks allowed people to be seen as they saw themselves, and as they wanted to be represented. To do so, he learned to earn the trust of his subjects. Especially for Life, he sometimes spent weeks with those he would photograph before even picking up a camera. “He showed a number of documentary photographers who followed him how to do that,” Brookman says.

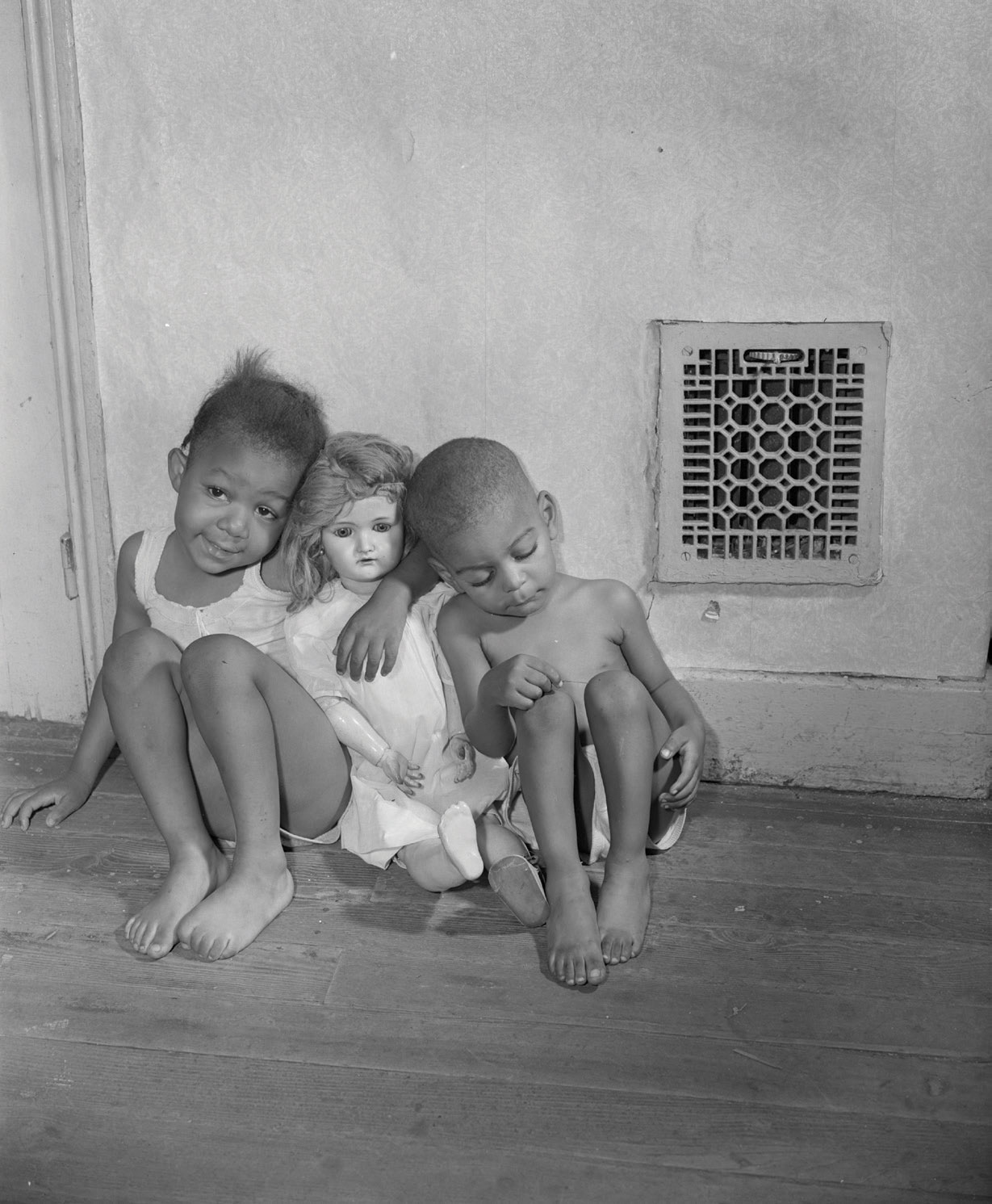

Washington, D.C. Grandchildren of Mrs. Ella Watson, a Government Charwoman (Children with Doll), July 1942 | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.4375 x 7.625 inches Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph

Deborah Willis, Chair of the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, contributed one of the exhibition catalogue’s insightful essays. Willis points out that Parks was very aware that showing “a self-possessed family living their lives against a backdrop of oppression could be just as potent [as images of oppression itself] in inspiring resistance and changing hearts and minds.”

And by mid-century, American mass media in the form of photo-intensive magazines, including Ebony, Life, and Look, offered a way to challenge stereotypes on a larger scale than ever before. As Willis puts it, Parks “believed that adversity favored no racial or ethnic group,” and his photography had the power to help viewers of all races relate to others’ experiences and feelings. Parks achieved this by combining acute visual intelligence with artistic sensibility and a desire to tell stories that radically inform but also generate empathy. As Brookman notes, “Parks has shown generations of young people and artists how to look at the world in new ways, and how to use photography and art to make the world a different place.”

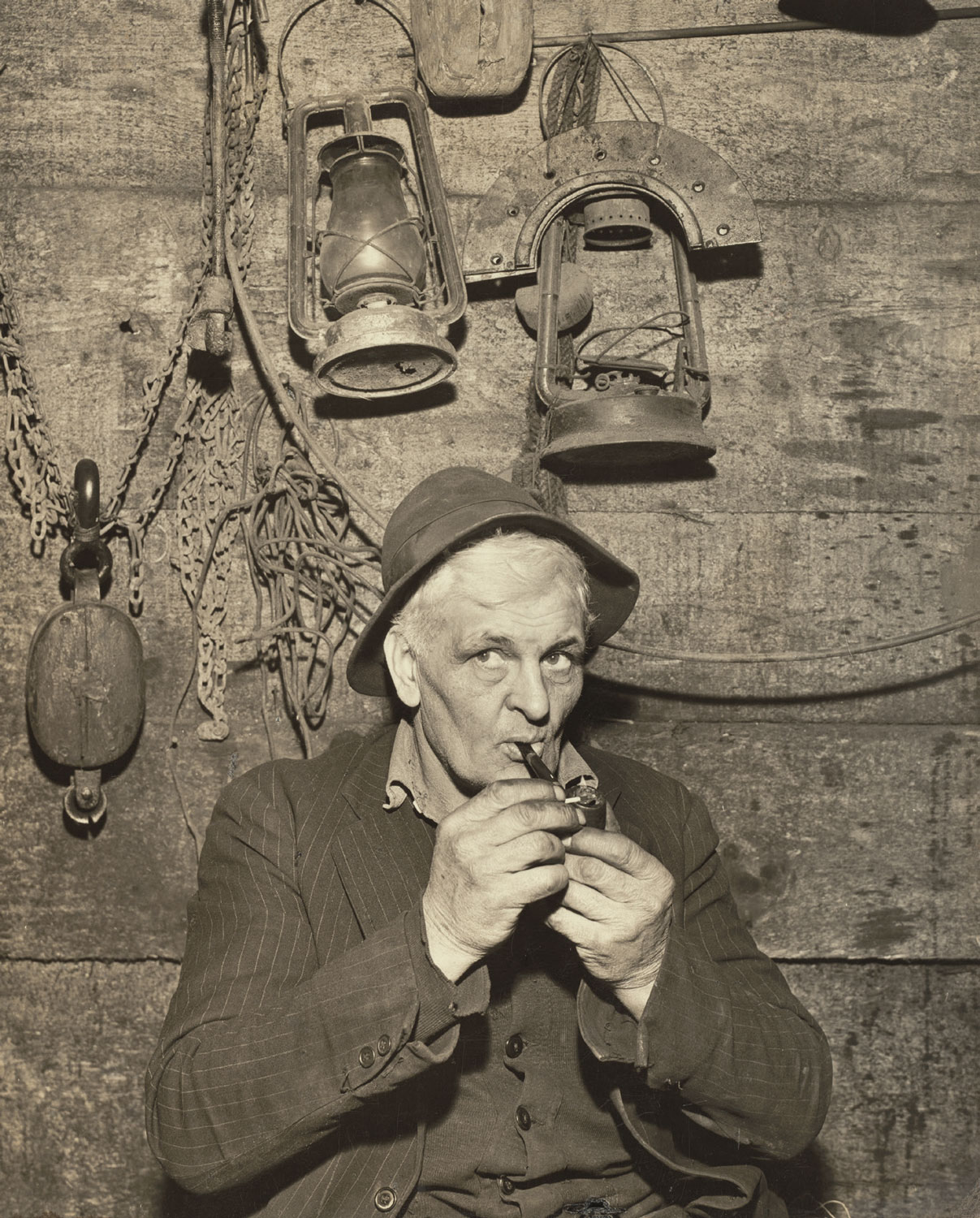

Captain Bill Lafond, 60-year-old Fisherman at Gloucester, Owns Three Boats. He is of Dutch French Ancestry and has been Going to Sea Since He was 13, November 1944 | Gelatin Silver Print | 13.125 x 10.375 inches | National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (TheGordonParksCollection) | Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

No Comments