17 May Entering George Carlson’s State of Wonder

IF GEORGE CARLSON HAD BEEN KEEPING FIELD NOTES in his shirt pocket — hand scrawled in pencil, referencing variations in color, tone, value, light and pattern — his method when hiking solo into the “channeled scablands” of the Pacific Northwest — the morning in question, which unfolded from the doorway of his red Swedish-style farmhouse in Idaho, might have been described like this:

5:30 am: Carlson, by habit, has risen like a crepuscular animal. Suffusing the indoor human space behind him is another Invention by J.S. Bach. Ahead, as he steps outside, an advancing sun, still dim, seeping forward into a sky holding a muted moon. The twilight fills rapidly with live dulcet birdsong, amping up slowly to mezzo-forte; whitetail deer, closer and pensive, have just emerged from the backwoods; farther out, an elk mother and her yearling extend the sightline into middle ground; the wapiti, holding cautious in profile, are well aware, as Carlson is, of mountain lion and bear presence, the cryptic big cats and bruins never far away, though for now, unseen.

The Bach piano piece flows through Carlson, spilling out toward a distant horizon as he interprets what he absorbs. Fading night has not yet yielded to morning; the artist’s cultivated space is edged by real tooth and claw wildness; tranquility is charged with expectation.

Carlson is listening to the composer and translating sonic notes into his own repertoire, visual ideas gelling in his head. He is too humble to draw a direct parallel between himself and Bach, though if an outsider delves deeper, pressing Carlson, one soon discovers that the same kind of structure Bach mastered in classical music informs Carlson’s approach to composition.

At age 68, nine years ago, Carlson returned to his original love — painting — four-and-a-half decades after he had become sidetracked by sculpture and acclaimed for it, believing his diversionary foray into three dimensions wouldn’t last as long as it did. Along the way, he had a one-man show at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and won the prestigious Prix de West gold medal for Courtship Flight in 1975.

Carlson`s sculpture today is in the permanent collections of the Denver Art Museum, the Whitney Gallery at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, the Autry Museum of American West, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Center, the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, and the Gilcrease.

In 2011, Carlson became the only artist in history to earn a second Prix de West gold medal in another medium, for a painting titled Umatilla Rock set in a landscape almost no one had ever heard of.

Carlson, to be sure, is a living enigma. He is the artist’s artist, a neo-Luddite throwback, that even technology-addled younger creative souls dream of becoming; he’s a painter’s painter after once being a sculptor’s sculptor; a serious, bookish, curious, intense recluse, with fire in his belly, finely attuned to a higher form of personal aesthetics.

“I have a strong belief in the mystical qualities of life. I know it’s unscientific and doesn’t have a thing to do with logic. But there are a lot of things that escape explanation. Those are the realms where my artistic explorations take me,” Carlson says. “I’m not interested in being seen. I’m content with just trying to enjoy the grand play, the big magic show that’s going on around us all the time.”

Before art historian Anne Morand passed away in 2013, I had a habit of visiting regularly with her. Morand had held down senior curatorial positions at the Gilcrease, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City which hosts Prix de West, and the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana.

“What work, by which living artist, most excites you,” I asked Morand one day.

Without a pause, she invoked George Carlson, pointing to a new acquisition made by the National Museum of Wildlife Art titled Passage At Dusk, a portrayal of a giant wing, an allegorical reflection on mortality, reminiscent of the angelic depictions of painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer.

“He, in my opinion, is the most talented interpreter of the natural contemporary West but I don’t consider George a Western artist, at least not in the way its subject matter has become so tightly delineated,” Morand said. “When George took up painting again full time, he gave up the stature he possessed as a sculptor and kind of blew people away because he seemed to be coming at it out of nowhere. It took courage. But it revealed what really resides inside of him. He’s one of those rare artists who has the creative dexterity to work ingeniously across mediums. For that. I consider him an American treasure.”

Born in Elmhurst, Illinois in 1940, Carlson’s art education was nurtured early.

His mother was a classical pianist who spent many weekends with her son at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2016 at the Autry Museum in Los Angeles, Carlson delivered a lecture on the impact of art education in his life. He cited a high school teacher, Glen Messersmith, who introduced students to formalism, i.e. the elements of aesthetics rooted in the DNA of the human psyche.

For the teenagers hearing it, Carlson says, Messersmith was really delivering pep talks on the importance of beauty into one’s life, as an antidote to despair and cynicism. “He was so full of zest and enthusiasm,” Carlson says. “He was like the Robin Williams character in “Dead Poet’s Society.” Whatever we were destined to become, he wanted us to continue the journey with our eyes wide open.”

Carlson went on to study at the American Academy of Art and the Art Institute in Chicago. Upon graduation, he paid his dues by landing a job first at Vogue Wright Studios and then accompanied his boss, Ralph Thompson, to Kranston Studios. Thompson not only encouraged Carlson to continue drawing from live models but to take up sculpture as a way to better understand the form.

In downtown Chicago, while working as a commercial illustrator just as many of the finest American painters did as part of their training, Carlson worked alongside a talent colleague named Dick Faron. In his private time, Faron was an Impressionist trying to make sense of modernism.

An intellectual old schooler, Faron engaged Carlson in many long discussions. “Dick always said a good piece of art gives of itself year after year,” Carlson shares. “He had a way of adding in abstract qualities and paid attention to all of the subtle aesthetics so that a painting could read one way when you stepped close and say something grander when you stepped back.”

In 1964, burned out on the tight deadlines of illustration, Carlson gave up commercial art and headed West, becoming a ski bum and dishwasher for a while in Aspen and Vail, Colorado, and Taos, New Mexico. Visits to Taos Pueblo sparked an admiration for the native seamlessness between between tradition, religion, art and spirit. His own consciousness stoked, he enrolled in the anthropology program at the University of Arizona in Tucson and started spending time with several different native tribes in the Southwest. His passion for fine art returned. He got to know the late Bettina Steinke, Robert Lougheed, and Boris Gilbertson in Santa Fe. Not long afterward, he and stone carver Steve Kestrel became friends. (Kestrel, in fact, helped build the custom rustic home and studio that George and Pam Carlson designed in Idaho.)

During the 1970s, Carlson had heard about the Tarahumara being a people who still adhered to their aboriginal lifeways. Based upon the recommendation of a native friend, he set out for the remote Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Mexico to spend time with them and slowly earned their trust. He sculpted on location in wax and clay and sketched in pastel.

With research trips broken up into two-month segments, he ended up spending the equivalent of a full year in their company over half a decade. “I don’t like to be a tourist. I prefer going into an area where I’m working and totally immersing myself in the subject be a culture or landscape.” Notoriously shy people, the Tarahumara warmed to Carlson and at one point the tribal leader invited him to marry one of his daughters and stay there permanently.

Carlson produced dozens of sculptures and hundreds of sketches. The works received instant national acclaim, earning him exhibitions at the Kennedy Galleries in New York and later at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. “I had a sense, even then, that what I was witnessing was on the brink of vanishing forever,” he says. “The old ways had survived but the Tarahumara were being rapidly inundated by outside forces.”

Carlson was well aware of the famed Taos artists’ interaction with native Americans, and he knew there had been tension and accusations that some of the subjects felt exploited. With the Tarahumara, not wanting to compromise the dignity of the rituals he was documenting for posterity, he engaged them with respect. Foremost, he observed and listened.

All along, guiding him, too, were the ethics of Loredo Taft. In 1923, Taft [1860-1946], who had studied at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and later taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, penned “The History of American Sculpture.” In that work, Taft observed that “the first requisite of any artist is intelligence and the second sympathy; but an artist is not compounded of these two elements alone…Taste must enter early into the artistic composition and skill and mastery must not tarry far behind.”

Sympathy is about more than sentiment or romance, Carlson says. It’s a true attitude of respect, a check against any compulsion one might have to exploit subject matter and it extends to landscapes as well as to life forms.

For Carlson there’s a difference between being sensitive and sentimental; the former drives a deeper conversation within himself; the latter is about eliciting an easy and superficial response in the viewer, something he rejects. He equates such sentimentality with kitschy calendar art and refuses to go there; it’s why he savors the out of the way and the overlooked in nature.

For years, the Carlsons in Idaho have courted solitude, having many visitors but rarely going into the city. Expressions of their tranquility are gardens planted with perennials to deliver constant blushes of color. In July, lavender erupts in front of a pergola not far from their rose garden on one side of their home and profusion of wildflowers on the other.

A short drive away, Carlson has a studio in a former church in Harrison where trappings of his sculpture career fill the old sanctuary. Upstairs is an impressive library with volumes on art history and works by naturalists, and philosophers. Off to one side is Carlson’s painting space, bathed in natural light that seems lit by an earlier era. It was there that he made a move, having become tired by the laborious, hand’s-on process of foundry work.

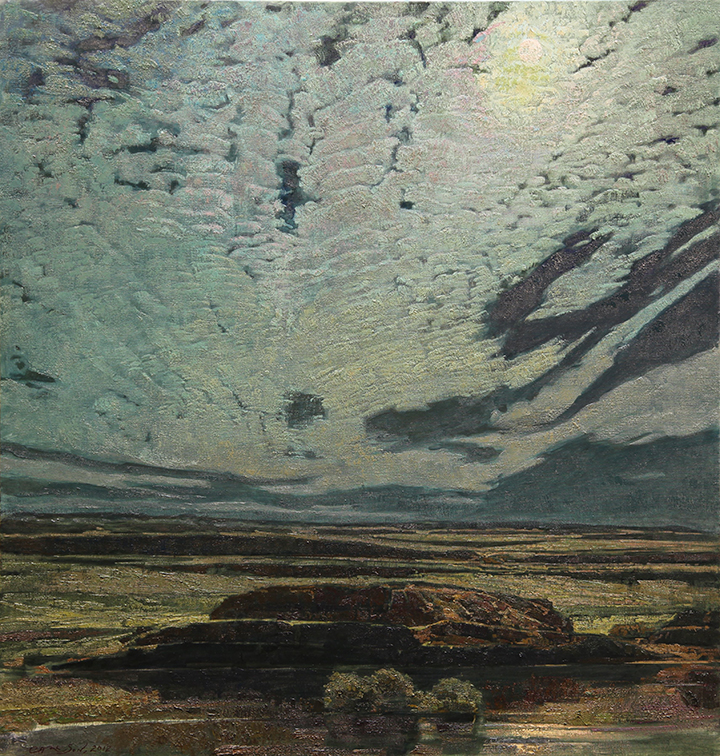

The Channeled Scablands in eastern Washington and northern Idaho are the result of an epic Ice Age flood, created after a glacial dam holding back the waters of ancient Lake Missoula breached. The torrent hurled on a downward path toward the Pacific Coast, violently scouring the bedrock, leaving behind exposed monoliths protruding from the undulating roll of the Palouse and the hardscrabble desert coulees. He took ideas out of the landscape while making trips between his studio and a foundry in Oregon. The ancient story and path of the scablands left him feeling tantalized. He began to photograph and sketch them. He contemplated painting, but groundwork needed to be laid.

Carlson created his own sophisticated color chart. It’s actually a book, roughly the size and thickness of a bible, with a palette of shades, dark to light, cool to warm, a sophisticated volume that he compiled methodically, mixing every hue to retrain his mind before ever raising a brush to easel in his studio. As a reference, he is able to match any color he finds in the field, no matter how nuanced or subtle.

Stone carver Tony Angell said many were puzzled when Carlson walked away from bronze. “He was doing these remarkable interpretations of human and non-human forms in bronze. Every one had such gravity and placement, like they were just getting on with what they were destined to become. A native shaman after he spent months of study in Mexico, or interpretations of light-footed ballet dancers in New York worthy of comparison to Degas. Or draft horses. So few ever reach that place of command and originality,” Angell says. “So I was surprised when he unceremoniously finished that part of his career — and strived to do the same thing with a brush. It took cojones.”

Carlson, of course, didn’t issue a press release. He simply exhibited a painting among a selection of his sculptures at Prix de West and it left people both stunned and confused. Angell saw no incongruity. “When thinking of Carlson’s landscapes, there is no separation from what he started doing 60 years ago, interpreting and exploring the form. He’s delving into his own relationship with the earth—its organic forms, no differently than if he were taking on a human or animals figure — and he has this wonderful, imaginative understanding of the cycles of nature. He takes us to the surface and then digs into the deepest elements of what we are and what we, as sentient beings, stand upon.”

Angell adds: “In every one of his paintings, I as a sculptor can feel my fingers tingle. I want to put my hands on them because he speaks the tactile truth of physical contact. His work catches the eye and are full of good purpose. I don’t know how many times people can portray a landscape but there is only one Carlson and when he does it, it is singular, distinguished, and genuine, regardless of whatever medium he chooses to employ.”

Artistic influences in Carlson’s life cover a gamut. With sculpture, he points to Degas and Rodin, Paolo Troubetzkoy and Medardo Rosso, among others. As far as painters, there’s Emil Carlsen, Anders Zorn, Antoni Tàpies, Antonio Mancini, Abbott H. Thayer and the late Bruce Kurland.

Sue Simpson Gallagher, owner of an eponymous gallery in Cody, Wyoming, had heard about Carlson for decades and had viewed his work in museums. In 2002, she attended a Carlson one-man show of horse sculptures hosted at Nicholas Fine Art in Billings, Montana.

“Everyone was talking about it. The show was extraordinary,” she says. “But I realized upon seeing it that although everyone was talking about the work, they were talking about George as a hero, a mentor, a demigod in the world of western art.”

A few years ago, in 2011, the Carlsons attended a show for Lawson, landscape a generation Carlson’s junior, who has become a good friend. Lawson, a native of Wyoming who makes his home in Maine, knew the late Andrew Wyeth and enjoys the company of his painter son, Jamie. The way that Carlson and the Wyeths talk and think about art is the same.

Lawson and Carlson hit it off. Lawson is one of the most acclaimed representational painters of his generation. A few months later, he phoned Carlson and confessed that he was struggling. “After going on for 10 minutes, I wondered if George was still on the line and then I heard this little sigh,” Lawson explains. “He said, ‘It sounds to me, Tim, like you are exactly where you need to be. Everything that I have ever found worthwhile takes place within the struggle. To hear it from him meant a great deal. As brilliant as he is, there’s no ego and, at the same time, no false modesty.”

Lawson recalls a recent exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, featuring the work of James McNeill Whistler. “There was one of Whistler’s nocturnes and when you stand 12 to 15 feet away, it’s like looking through a window. But move closer and everything you’ve just seen starts to disappear,” Lawson says. “Get really close and there’s nothing there. George’s paintings have the same effect but they operate on the other end of the textural spectrum. Get close and the scene dissolves into pure abstraction, an interwoven maze of sculpted paint.”

Lawson holds Carlson with the same level of esteem as Wyeth. “His work embodies everything I admire. It’s representational but it’s not. It could easily be seen as total abstraction. There is mystery to it and at the same time, a quietness,” he says. “There are a lot of really good painters right now and it’s an exciting time to be in the profession. But nobody that I’m aware of in this country is on the same level as George. He stands alone.”

A positive, encouraging proponent of good art and a mentor to talents like Lawson, Carlson admires perseverance, experimentation and ingenuity, Simpson-Gallagher says. “He is a generous spirited man who values friendship, loyalty, commitment and kindness,” she notes, then adds something else: Carlson is a partner who treasures his wife. “His respect and appreciation for Pam make him even more lovable. They are a terrific team. They make each other better people. Pam is the perfect artist helpmate. She is also grace incarnate,” she says.

Simpson-Gallagher wasn’t surprised by the public reception that greeted Carlson when he switched from three to two dimensions nearly a decade ago and he’s regularly won artist choice awards at Prix de West. “Now as I view George’s paintings I see that the medium is not what is most important, it is the vision and its translation that matters for him. His technical prowess is unmatched in the world of painting today and his art spirit is unparalleled. He is able to take a place or an idea of a place and make it sacred,” she says. “It’s what makes the artists I see at shows standing in front of one of George’s paintings ask each other “how do you think he does it?”

Scuffing his surfaces, applying paint then sanding them back, sometimes relentlessly until he achieves the coarseness of earth he’s portraying, Carlson acknowledges he wants his works to exude tactility, to have the sensation of a visual encounter reverberate at the gut level. “I obviously like texture. I like working with malleable materials,” he says, noting that he feels kinship with the anonymous Cro-Magnon artists who painted in the caves of Lascaux, grounding their own pigments and applying paint with their own hands. “They’ve been on the walls for millennia and they still exude vitality. There was no artificial distancing between what they experienced in their world and their expression of it. It still reads fresh.”

“People say they have classical music playing as background while they work. It is never background for me. It moves me into a subconscious state when I forget about the painting and am thinking about what I’m hearing,” he says.

When Bach plays major and minor keys, Carlson explains, he is essentially playing cools and darks, to put it in the parlance of painting. “To me, music and painting are interchangeable with the use of language to describe what is happening in a piece.” Color is a note. Modulation and variation are plays in value and tone; design speaks to rhythm and harmony is harmony. Just as you know it when you hear it in a musical composition, he says, the eye and the brain and the heart feel the synchronicity. “We exist because of our sensual response to nature; the world we’ve created is shaped by it and I believe that our disharmony is a result of not listening to what’s happening around us.”

Many of Carlson’s works these days are massive, typically within the dimension of 40 x 40 inches. Steptoe Butte, submitted to Autry’s 2016 Masters of the West, was inspired by listening to a Bach piece in the early morning, as the performing musician played the scales back and forth with subtleties and innuendos. “The left hand plays a different melody from the right hand and they serve as counterpoints until eventually merging,” Carlson says. “For me, diagonal and horizontal lines serve the same purposes as his melodies on a path toward convergence.”

In Song of the Earth, a submission to Prix de West, Carlson explores the advance of spring in the pastoral Palouse. Magpies with raspy voices are portrayed in the foreground, the luminescent patterns on their wings echoed in receding fields of grain lined with streaks of fallow earth tones, green-up and melting snowdrifts. The work was inspired by a Mozart sonata form where the beginning circles back upon itself in the crescendo.

Subtly, he is using temperature to push perspective backward or pull it forward. While striving to convey the rhythms, hum and energy of the earth, he paradoxically eschews employing loud primary colors, believing it better to be underactive with palette than resorting to blinding colors which to Carlson equate to dissonance. “Taste in a painting has to do with restraint. I think as an artist it’s important to be serious, but playful,” he says.

When he listens to classic music, he tries to become totally empty, to void himself of the extraneous, and let each note come through, he says, “like pure drops of water hitting a plant in the sunlight. Every note reflects the world. Only when the outside noise goes quiet and I surrender myself to hearing what the music is telling me, can I even attempt to achieve a similar kind of harmony visually.”

Every day Carlson makes a trek into his 55-acre backwoods. It’s in those hills where he methodically, over the last 30 years, carved a looping trail by hand. On this morning he’s meeting with a local logger. He’ll tell the sawyer to thin out aspects of the overgrown canopy, not to topple old trees for merchantable timber, but to make the diverse coniferous and deciduous glens more resilient and healthier. He is thinking about how his personal sanctuary will be years from now after he is gone.

Reflecting on the morning when he watched the deer and elk in his yard, following an evening when he mountain lion scat on his hiking trail, he says, “Isn’t it revealing, except for a predator and prey encounter when life and death converge, how nature never seems to be in a hurry. Her beauty is prolific but not accidental. It’s the culmination of so many miraculous events intertwined on this planet, that we take so for granted,” he says. “In the entire known cosmos, the forces of life have aligned here and yet so many of us are caught up chasing things that don’t really matter.”

Similarly, he says, busyness in painting is the opposite of meditation. “If you provide all of the answers, there is no need for viewer participation and reflection,” he says. “I don’t like to invoke a word like spiritual because I think it is overused. But when I get into the zone of concentration, it is almost like entering a sacred space and for me, I guess, it’s the closet thing I can do to dwell in a prayer.”

Todd Wilkinson, a contributing editor to WA&A, has been writing about art and the environment for decades. He is author of the recent critically acclaimed book Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek (mangelsen.com/grizzly) featuring the images of famed American nature photographer Thomas D. Mangelsen.

- “Sunlight and Shadow” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 42 x 42 inches

- “Ice Patterns” (detail, click to expand) | Oil on Linen | 30 x 38 inches

- “Echo of the Former World” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 33 x 42 inches

- “Basalt Cliffs” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 42 x 42 inches

- “Steptoe Butte” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 42 x 39 inches

- “Sunlight and Shadow” | 2015 | Oil on Linen| 42 x 42 inches

- “The Tempest” | Oil on Linen| 42 x 38 inches

- “Stillness in Moonlight” | 2012 | Oil on Linen | 42 x 40 inches

No Comments