31 Oct MARDI GRAS COWBOY

During his decades-long, successful illustration career, when Robert Rodriguez imagined himself eventually moving into fine art, he was clear about what he didn’t want to do. He was not interested in imagery that was dramatic or grandiose. He didn’t see himself using gaudy colors. And he certainly was finished with having art directors constantly telling him to change what they had explicitly asked him to do. In short, after producing countless illustrations whose express purpose was to catch the eye, he imagined being free to paint what he jokingly called “ugly pictures.”

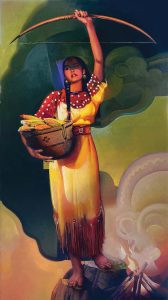

The Picture Over Nellie Page’s Bar | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 24 inches

Rodriguez’s art is anything but ugly. But liberation from the creative constraints of other people’s ideas means his work these days can be honest reflections of things that are most important to him in life. “I like simple, real, calm, romantic stories,” he says, sitting in his Los Alamitos studio in Southern California. He loves the imagery and mythology of the Old West and considers himself a Western artist, but also gives himself permission to be sparked by diverse sources of inspiration and to paint a wide range of subjects, from Native American figures to seascapes to orange crate labels of his own fictional brand.

Rodriguez made the shift from illustration to full-time fine art just four years ago and almost immediately began to be noticed by collectors and others in the Western art world. He was accepted into major invitational shows, including the Museum of Western Art’s Roundup exhibition in Kerrville, Texas, the C.M. Russell Museum’s annual Russell Auction, the Out West Art Show in Great Falls, Montana, and the Mountain Oyster Club’s annual art show in Tucson, Arizona, where he earned the award for best new artist in 2021.

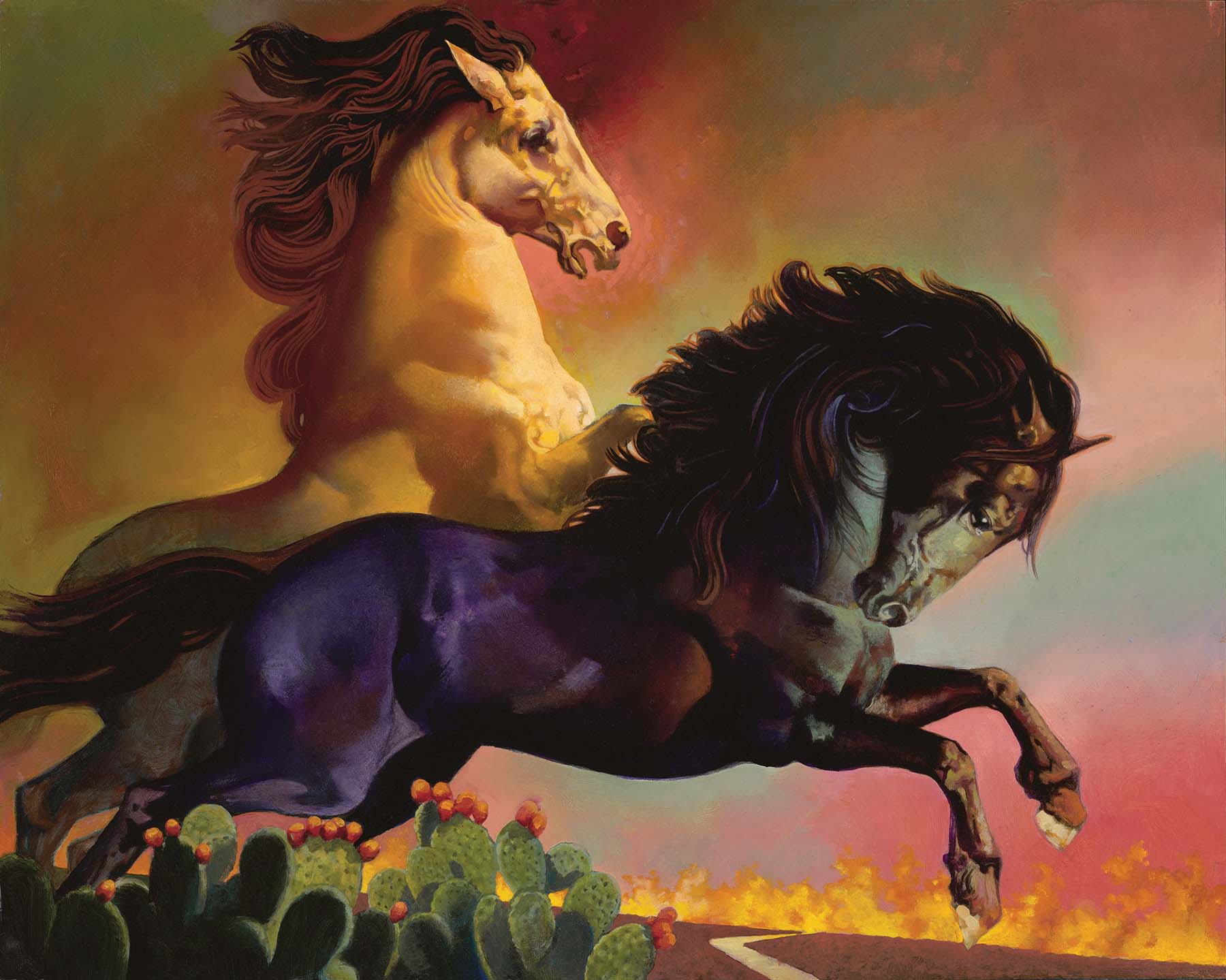

Mexican Parade Saddle | Oil on Canvas with Cold Wax Medium | 48 x 36 inches

“Robert’s fine art is viewed through the lens of an expansive life of illustration,” says Mark Sublette, owner of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson. “Multi-threads of observation, execution, and imagination can be found in each painting, a feat few other artists can match.”

War and Peace | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 20 inches

When it comes to his roots, Rodriguez would like to be able to say he was raised on a vast cattle ranch in the Rocky Mountain foothills, living the cowboy life. In reality, he calls himself a “Mardi Gras cowboy,” having grown up primarily in New Orleans. But his boyhood imagination was as wild as the Old West. He planted himself in front of the TV after school to watch his favorite 1950s-era cowboys, and had lunch boxes with images of Roy Rogers and Hopalong Cassidy. Later, as a painter, he was equally inspired by such Western ephemera as movie posters and pulp magazine covers from the 1940s and ’50s. “I still paint the fantasy and mythology of the Old West,” he says.

Rodriguez finally visited the West in middle school, when his father moved the family to the Los Angeles area to work as a lighting engineer in the film industry. For young Robert, the move meant real art classes for the first time and an introduction to a variety of media. He greatly missed these after his family moved back to New Orleans as he was starting high school. And although he later applied to art schools around the country, he really only wanted to return to L.A.

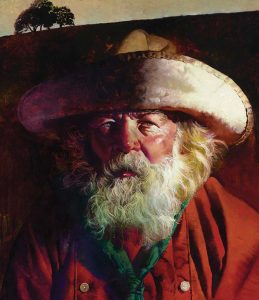

The 49’er — The Stories He Could Tell | Oil on Canvas | 28 x 24 inches

So he did, graduating in 1969 from Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in illustration. He immediately began working in the field, and for almost 40 years, the work never slowed down. At one point, he was represented by six art agents from San Francisco to New York. He also taught illustration for 15 years at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, inspiring his students as much as he was inspired by them.

Rodriguez’s paintings became posters for movies, the Super Bowl, Ringling Bros. Circus, and Broadway theater shows, as well as U.S. postage stamps, including the series Cowboys of the Silver Screen. These stamps, featuring Tom Mix, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and William S. Hart, were a delight to create, he says. “It was like bringing back my childhood. It was so wonderful.”

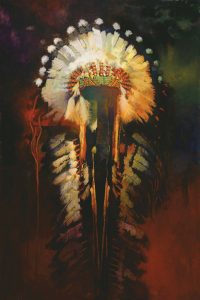

Arapaho Warbonnet | Oil on Canvas with Cold Wax Medium | 36 x 24 inches

Rodriguez also produced images that became familiar to millions of Americans: the Old Quaker on oats containers, the Santitas Corn Chips senorita, and the kindly grandma on packages of Grandma’s Cookies. He enjoyed illustration and never minded molding his skills to an assigned concept — except for the fact that art directors, for no reason he could discern, inevitably required him to alter the images they had requested. He quips that a subject’s shirt color might need to be changed because the art director’s wife didn’t like green.

Then came an illustration job that blew the creativity doors wide open and pointed to a future in fine art. It was 1998 and Rodriguez was talking with a client who imported absinthe. The client mentioned that he was headed to New Orleans for Tales of the Cocktail, an annual gathering for the global liquor industry. The artist had never heard of the event but quickly realized it could use a poster. He knew he couldn’t just cold call the group and send a painting, expecting them to pay his usual rate. So he proposed a deal: He would create the poster image for free in exchange for being able to sell posters at the event, even giving the organization 10 percent of what he made.

They agreed, and for nine years Rodriguez was given free rein to design and paint the official Tales of the Cocktail poster. The organizers didn’t even ask for sketches and never requested changes. “I got spoiled. They’d tell me the cocktail they wanted to promote and the theme for that year, and I’d come up with an image, my choice,” he says. “The freedom was intoxicating.”

Little Wing | Oil on Canvas | 26 x 28 inches

In 2020, he began shifting from illustrations in acrylic to his own imagery in oils and was quickly accepted into art shows. Says Darrell Beauchamp, executive director of the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, “Because he comes from an illustrator background, Robert brings a fresh, colorful view to the Western art world. His work is unique, crisp, and non-traditional, and that’s what I love about it.”

While Rodriguez was ready to leave illustration, initially, he did have one concern: Without someone telling him what to paint, would he come up with enough ideas of his own? He needn’t have worried. “The floodgates opened. I have pages and pages of ideas,” he says.

Among his recent works is Arapaho Warbonnet, a richly-hued depiction of a feathered and beaded headdress against a dark background. When asked by a viewer why there was no warrior wearing it, he explained that the painting was not about an individual but about the artwork that was the warbonnet itself. At the same time, he says that his simple, abstract sketch for the piece was inspired by the work of the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt. “I have a lot of influences, though they aren’t often noticeable,” he says.

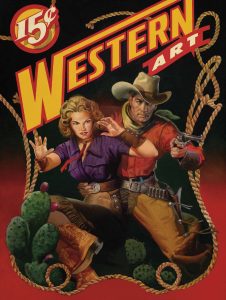

15¢ Western Art | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 36 inches

The title of another piece, The Picture Over Nellie Page’s Bar, contains a Western reference even though its stylistic inspiration is Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian and its subject is a woman floating above a romantic landscape with arms full of flowers and fruit. In the 1965 Western comedy film “Cat Ballou,” a railroad tycoon tries to impress a woman played by Jane Fonda. Looking at his art collection, she says they’re the most gorgeous paintings she’s ever seen: “Almost as pretty as the picture of the girl with the fruit over Nellie Page’s bar.” Rodriguez smiles. “This is my idea of that painting over Nellie’s bar. It looks like something that would be in a saloon.”

Rodriguez frequently paints women and is fascinated by female figures in Greek mythology and Native American legends. Future paintings may emerge, for example, from the striking similarities between the story of Demeter, the Greek goddess of the harvest and fertility, and the Blue Corn Maiden of Pueblo mythology, both explaining why crops only grow in summer.

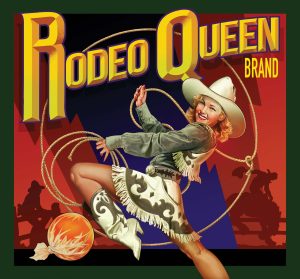

Rodeo Queen | Oil on Canvas | 26 x 28 inches

Other imagery flows from stories closer to home. The artist has begun a piece depicting a young woman on the prairie, her sod hut in the background. She has stopped plowing and appears to be wishing on a dandelion, blowing seeds into the sky. Her hand rests on her stomach, suggesting she is pregnant. The painting was inspired by Rodriguez’s great-grandmother, who was plowing her field in Louisiana when she stopped, went inside, and delivered her baby. Family lore says she returned to the field to finish up the plowing before sunset. “I always questioned that last bit,” he says. “But this lady was 5-foot-2 and had nine kids, and she was tough. So maybe it’s true.”

In any case, what Rodriguez aims for in his work is a level of truth that expresses the universal human experience, regardless of culture or time. He likes to suggest a narrative but leaves it open-ended. “I want people to bring their own thoughts to it,” he says, adding that, in essence, he thinks of his paintings as “magical, mythological, human stories.”

No Comments