09 May Historic Theaters of the American West

THEATERS WERE GLORIOUS PALACES in the Roaring Twenties and the Depression Era of the 1930s, when motion pictures were one of America’s greatest industries; palaces where men wore suits and ties and women dressed in their Sunday best. They were architectural gems with ornate decoration, unique marquees, creative themes and a transportive quality that so aptly complemented the performances inside.

By the mid-20th century, however, many theaters were gone with the wind, derelict, disowned and

By the mid-20th century, however, many theaters were gone with the wind, derelict, disowned and  forgotten relics of another age. However, throughout the U.S., communities have undertaken the preservation of these architecturally diverse structures, and these iconic gathering places, that once defined towns for generations, are now doing it again.

forgotten relics of another age. However, throughout the U.S., communities have undertaken the preservation of these architecturally diverse structures, and these iconic gathering places, that once defined towns for generations, are now doing it again.

Majestic Theatre | San Antonio, Texas

When the Majestic Theatre opened in 1929, it was the largest in Texas and the second-largest in the U.S., seating more than 2,000 people. It was also the first theater in Texas to be fully air-conditioned, a major attraction in the hot climate of San Antonio.

It gained fame, as well, for its Spanish Mission, Baroque and Mediterranean elements. The atmospheric theater was designed by architect John Eberson as a fantasy villa, with tall glass towers, “flying” taxidermied doves and painted grapevines along the walls. A rare, white, stuffed peacock perches on a balcony railing, and the vaulted auditorium “sky” twinkles, as a cloud projector and small bulbs — placed in the same configuration as the stars on the theater’s opening night — simulate the sky.

The Majestic closed “forever” in December 1974, but was soon donated to the city in 1976. Following a subsequent renovation, it reopened in 1989 as home to the San Antonio Symphony. To date, the Majestic has hosted more than 4 million patrons and performances, from comedian Chris Rock to Broadway musicals.

The Majestic closed “forever” in December 1974, but was soon donated to the city in 1976. Following a subsequent renovation, it reopened in 1989 as home to the San Antonio Symphony. To date, the Majestic has hosted more than 4 million patrons and performances, from comedian Chris Rock to Broadway musicals.

Central City Opera | Central City, Colorado

When the Central City Opera opened in 1878, there were still gunfights in the street outside. Built by Welsh and Cornish miners who had settled in Central City to work, the 750-seat opera house cost a whopping $23,000. (And, yes, even in those wild-and-woolly days, this facility was built purposely for opera!) Locals pitched in during construction, but prominent Denver architect Robert S. Roeschlaub designed the elegant stone structure, and San Francisco artist John C. Massman painted the elaborate trompe l’oeil murals inside.

The theater’s glory years following the 1878 grand opening were short-lived; when the mines closed, so did the opera, and this beautiful facility fell into disrepair. In 1932, the building underwent an extensive renovation and reopened with Lillian Gish starring in “Camille.”

The theater’s glory years following the 1878 grand opening were short-lived; when the mines closed, so did the opera, and this beautiful facility fell into disrepair. In 1932, the building underwent an extensive renovation and reopened with Lillian Gish starring in “Camille.”

Today, each of the 550 plush seats is inscribed with the name of a pioneer or a celebrity

Today, each of the 550 plush seats is inscribed with the name of a pioneer or a celebrity who has performed here. The Renaissance Revival stone building is the oldest surviving opera house in Colorado.

who has performed here. The Renaissance Revival stone building is the oldest surviving opera house in Colorado.

Panida Theater | Sandpoint, Idaho

On opening day in 1927, owner Frank C. Weskil dedicated his new theater “to the people of the PAN-handle of IDA-ho” (hence the name). Built in only five months, the Panida stayed open through the Depression and World War II, despite the downturn of the lumber industry in the region. In 1980, however, a new theater complex opened and the Panida closed soon after.

In 1985, the theater seemed destined for the wrecking ball, as huge chunks of ceiling came crashing down. According to an article written by Patrick Jacobs in the Spokesman Review, “the theater was so rundown and rickety that it was being used merely as storage for the local drama troupe, the Unicorn Theater Co., which held performances in safer venues.”

In 1985, the theater seemed destined for the wrecking ball, as huge chunks of ceiling came crashing down. According to an article written by Patrick Jacobs in the Spokesman Review, “the theater was so rundown and rickety that it was being used merely as storage for the local drama troupe, the Unicorn Theater Co., which held performances in safer venues.”

Panida photos: AllerGale Design

But community members saw its value and spearheaded a drive to buy the theater. They raised funds, in part, by selling handpainted lobby tiles and personalized sidewalk bricks to supporters, including the mayor and the governor.

“We are the anchor to our downtown and the heart of our community,” says Patricia Walker White, executive director. “Our marquee lights up and draws patrons to local establishments; that’s provided stability to our downtown.”

Peery’s Egyptian Theater | Ogden, Utah

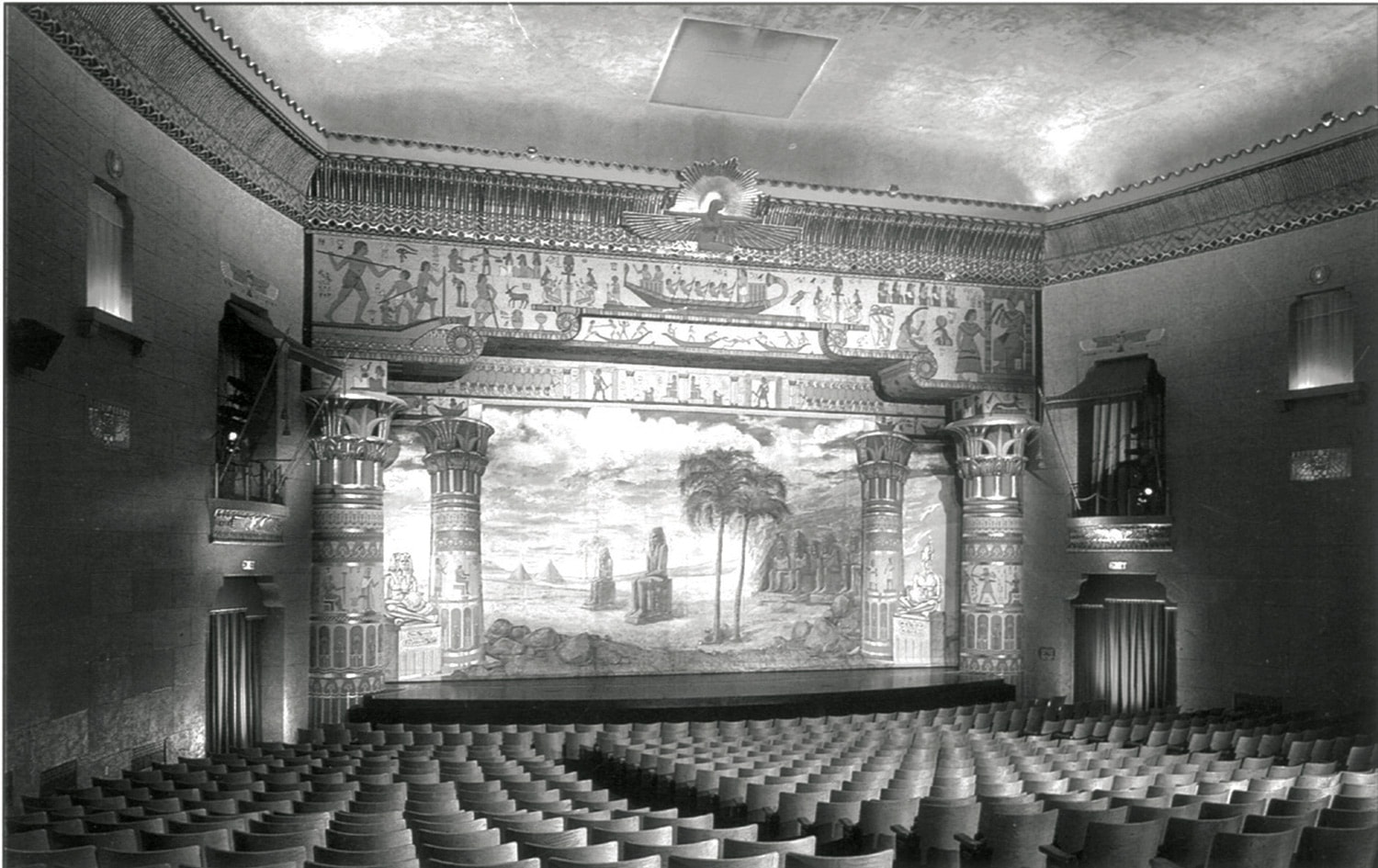

In 1922, King Tut’s tomb was discovered, and suddenly ancient-Egyptian design was all the rage. When Peery’s Egyptian Theater opened in 1924, it included an early form of air-conditioning: Big glass grates were installed and ice blocks put into them, then fans would blow cool air into the theater.

By the 1980s, though, Peery’s was showing only second-run movies, and in 1985 the Board of Health shut it down. Demolition was scheduled, and wrecking balls were actually at the door. But Ogden citizens passed a $30-million bond bill for construction of a convention center and restoration of the theater next door.

Now, Peery’s Egyptian Theater is one of a handful of Egyptian-style theaters left in the U.S. “This theater is truly an experience,” says Kassi Bybee, general manager of the convention center and theater. “It’s breathtaking to walk inside, and now it’s making memories for a whole new generation.”

Fox Theatre | Hutchinson, Kansas

Vernon M. Wiley built and opened the Fox in 1931 as a “movie palace,” where people could escape the Great Depression. And a palace it was. The building was constructed with Art Deco flair, in fashion at that time, with roof lanterns and a bright, glamorous marquee.

Vernon M. Wiley built and opened the Fox in 1931 as a “movie palace,” where people could escape the Great Depression. And a palace it was. The building was constructed with Art Deco flair, in fashion at that time, with roof lanterns and a bright, glamorous marquee.

Fox Theater images: CALgraphy Images, Larry Carver

The $400,000 it cost to build the theater would be around $14-million today. When it  opened, the Fox was the largest movie theater between Kansas City and Denver.

opened, the Fox was the largest movie theater between Kansas City and Denver.

It closed in 1985, however, victim to multiplexes and changing tastes. Devoted citizens formed a corporation which purchased it in 1990, and a $4.5-million restoration commenced the next year. After nearly a decade of work, the theater reopened in 1999, with movies, musical acts, popular stage productions and comedians.

Paramount Theatre | Oakland, California

Paramount Theatre | Oakland, California

Designed by prominent San Francisco architect Timothy L. Pflueger, and completed in late 1931, the Paramount was one of the first Depression-era buildings to incorporate the work of numerous creative artists into its architecture, according to the theater.

The creative talent of many resulted in a harmonious whole, with a nearly 60-foot-tall grand lobby, luminescent grillwork, rare wood and Italian marble. Its auditorium is unmatched in beauty, with golden walls and sculpted motifs from the Bible and mythology.

The building was purchased by the Oakland Symphony in 1972, after suffering three decades of neglect. Restored to its original splendor, meticulously maintained and fully upgraded to modern technical standards, the Paramount now serves all the arts.

No Comments