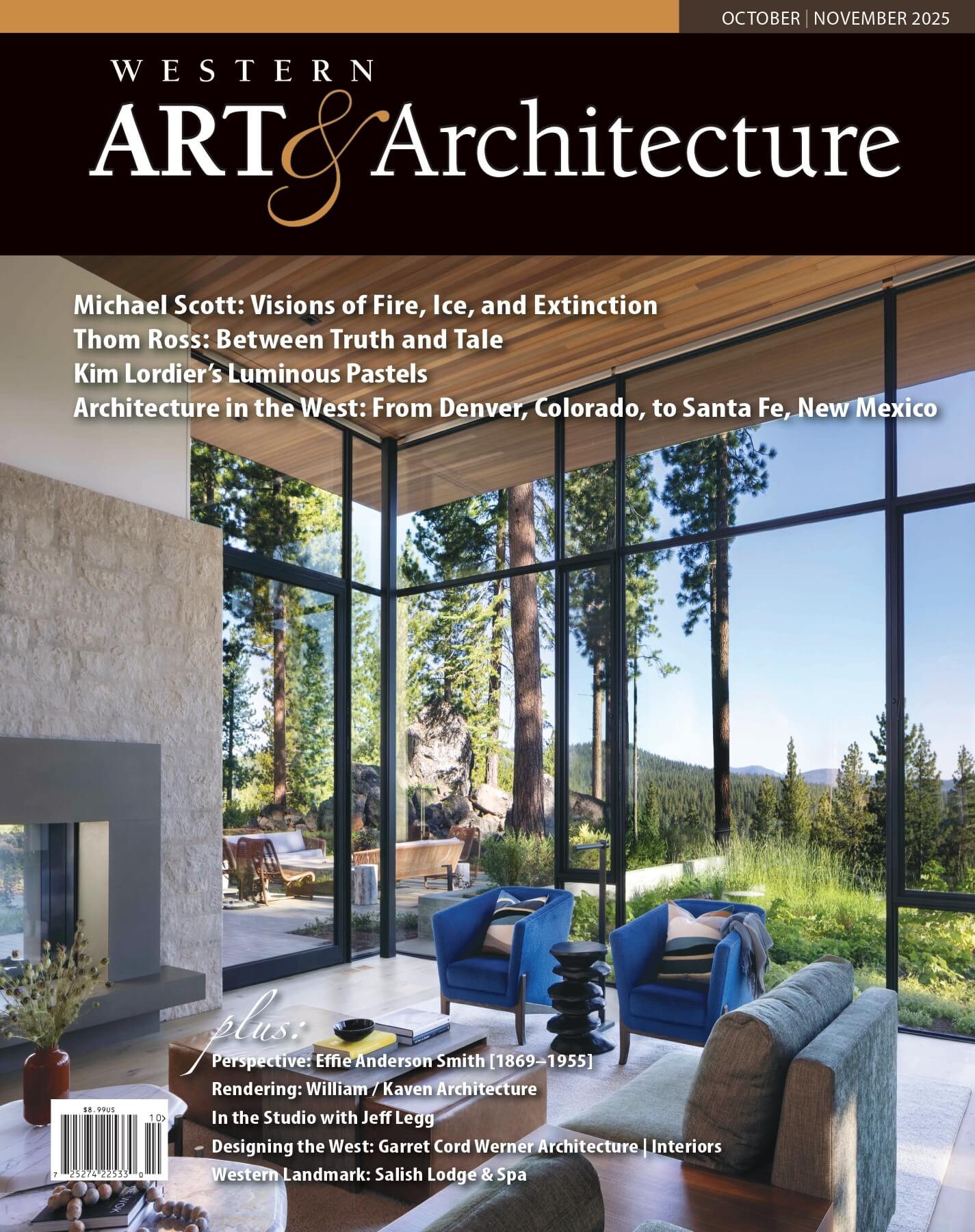

15 Mar In the Studio: The Sky’s the Limit

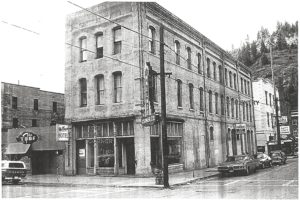

Ryder Gauteraux’s vision exceeds a single artistic pursuit. And similarly, instead of one studio, he works out of three places, none of which are conventional. Two studios are buildings in Wallace, Idaho, from the early 20th century — he rents one, purchased the other and is restoring it into a multi-use hotel — while the third studio is… Wallace itself.

Wallace Corner Hotel, photo: Historic Wallace District Mining Museum

“This whole town is my studio,” says Gauteraux (pronounced ga-trow), who identifies with the town’s rugged individualism and eclectic character.

Once the remodel of the former Wallace Corner Hotel is complete, Gauteraux will have a building-sized showcase of his varied interests: leatherworking and bootmaking, but also silver casting, sculpting, custom furnishings and whatever else excites his curiosity and ambition. Gauteraux believes in meeting clients and delivering their designs in person, and plans to invite clients to visit him and experience the unique, authentic Western charm of his adopted town.

have a building-sized showcase of his varied interests: leatherworking and bootmaking, but also silver casting, sculpting, custom furnishings and whatever else excites his curiosity and ambition. Gauteraux believes in meeting clients and delivering their designs in person, and plans to invite clients to visit him and experience the unique, authentic Western charm of his adopted town.

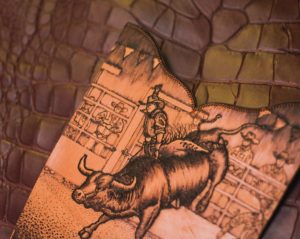

Gauteraux works on custom orders in his shop in Wallace, Idaho. Sometimes he collaborates with others, as he did for the pyrography on the boots shown here.

As with Gauteraux, Wallace understands boom or bust. A hardscrabble silver mining town devastated by an 1890 fire, Wallace wisely rebuilt using resilient brick, only to be followed by the 1910 Great Fire (also known as the “Big Burn”), the largest-ever U.S. forest fire, consuming 3 million acres and many local lives. But residents persisted and flourished.

Wallace’s rowdy side — gambling, liquor and brothels (an unpopular FBI raid in 1991 closed the remaining bordello) — is balanced with refinement. Into the early 20th century, moneyed folk from Spokane, Washington, built extravagant homes

Wallace’s rowdy side — gambling, liquor and brothels (an unpopular FBI raid in 1991 closed the remaining bordello) — is balanced with refinement. Into the early 20th century, moneyed folk from Spokane, Washington, built extravagant homes  in Wallace, while public buildings, such as Wallace’s Carnegie Library, sported porticos and pillars of the Renaissance Revival. The entire town is on the National Historic Register, and the architectural mish-mash only adds to its charm.

in Wallace, while public buildings, such as Wallace’s Carnegie Library, sported porticos and pillars of the Renaissance Revival. The entire town is on the National Historic Register, and the architectural mish-mash only adds to its charm.

Wallace has stayed in the public eye, such as for the 1996 filming of “Dante’s Peak.” The community celebrates its heritage in intriguing ways, with the Oasis Bordello Museum and a not-entirely-in-jest claim by the 2004 mayor that Wallace is the “Center of the Universe” (so says a circular plaque embedded in the street). But it has also embraced its proximity to ski resorts and other outdoor pursuits.

Gauteraux’s journey has followed a metaphorically similar course. Born in 1973, he was raised in a central Oregon log cabin built by his parents and purposely lacking electricity. The challenge and rigor of rodeo, especially broncos but also bull riding, appealed to Gauteraux right out of high school. He competed in the ring,

Gauteraux’s journey has followed a metaphorically similar course. Born in 1973, he was raised in a central Oregon log cabin built by his parents and purposely lacking electricity. The challenge and rigor of rodeo, especially broncos but also bull riding, appealed to Gauteraux right out of high school. He competed in the ring,  attended some college, had some setbacks, started a family and taught himself leatherworking out of necessity (his first endeavor was his chaps), deconstructing items to develop his intuition with materials and process.

attended some college, had some setbacks, started a family and taught himself leatherworking out of necessity (his first endeavor was his chaps), deconstructing items to develop his intuition with materials and process.

As Gauteraux’s passion for riding waned, leatherworking moved to center stage. He opened a retail shop with fellow cowboys in Oregon, appeared in publications such as American Cowboy and participated in design shows throughout Texas, Montana and Wyoming.

As Gauteraux’s passion for riding waned, leatherworking moved to center stage. He opened a retail shop with fellow cowboys in Oregon, appeared in publications such as American Cowboy and participated in design shows throughout Texas, Montana and Wyoming.

Boots weren’t the only thing getting Gauteraux noticed. He teamed with Oklahoma-based bootmaker Lisa Sorrel on the Norseman Designs West’s Studebaker Route 66 Club Chair, which won the Historical Craftsmanship award at the 2009 Western Design Conference. And he joined a cadre of artists to complete his biggest job-to-date: Daimler’s award-winning Western Star Low-Max Truck, for which he used 30 sides of tooling leather to customize the saddlebags, gas tanks and other features on the big rig.

Gauteraux’s shop, inside a turn-ofthe- century building, is full of the tools of his trade, including an elaborate polishing machine, various sewing machines and shoe forms for his custom boots and shoes.

Memorabilia from Gauteraux’s bronc-riding days surrounds the old bar in his shop.

This horse and rider will eventually be cast in bronze.

Collaborations are key to Gauteraux’s process, from clients to fellow artists such as beader Jade-Ann Robinson and pyrography artist Dyrk Godby. In 2013, A&E Channel’s “Rodeo Girls” star and actress-turned-barrel-racer Darcy LaPier enlisted Gauteraux to collaborate on ready-to-wear and one-off boots. Gauteraux’s hands-on approach included taking LaPier alligator hunting in Texas for the hides.

Building custom boots, says Gauteraux, “created the support for my family, and it’s also the tool that allowed me to do these other things.” Gauteraux taught himself lost wax casting, for example, to create silver jewelry such as the pendant he wears: a bronco rider atop a Celtic-looking spade.

Gauteraux wears a silver pendant, his first attempt at jewelry making.

Bronze casting is next up for Gauteraux, whose 4-foot-long sculpture, tentatively titled Respect, is inspired by the tradition of sculptors Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, as well as Colorado cowboy-turned-artist Greg Kelsey.

These golf shoes are made from alligator hide.

Gauteraux’s sculpture studio is little more than an unfinished room in the hotel where he’s converting 20-plus rooms to a handful, and adding a martini bar upstairs to complement the existing coffee shop downstairs. Slung over a makeshift seat using his grandfather’s saddle, Gauteraux works from photos of bison, horses and figures, but also from his gut. “When I really develop this idea for something, the only way to get it out is to complete it,” says Gauteraux.

He often works on several projects simultaneously. Around the corner from the hotel, Gauteraux does casting and leatherworking out of a rented brick building. His office in the front room includes a well-stocked bar from the last operating bordello in Colorado, loaned to him by a friend in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. People have given him or loaned him things, he says, because they understand his vision.

The first pair of boots he made were his own.

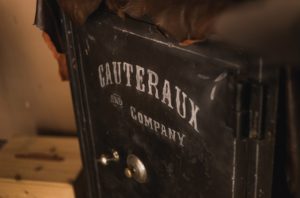

Gauteraux painted the safe that bears his family name.

Boots he made for his daughter feature artwork by Tracey Gauteraux.

Behind his office, which may eventually be a working showroom, Gauteraux has a tidy shop filled with the tools of his trade: leather, dyes, threads of all colors, shoe forms and machines for transforming leather into functional works of art.

Daimler’s commissioned truck is replete with Gauteraux’s custom saddlebags and leatherwork.

What interests him, he says, is process, especially telling a vital story through sculpture, the building he’s transforming and bootmaking, by which he’s still challenged. “The part about the boots that still thrills me is the people I build them for,” says Gauteraux, who declines to name-drop, although with prices starting at several thousand and taking a year or more to complete, one can imagine his clients are as extraordinary as the boots and other items they commission him to design. The only commonality in his clients, says Gauteraux, is a particular quality he himself admires. “They’re all self-made.”

What’s next for Gauteraux?

Details of custom stitching he did for John Gallis Norseman Designs West. Image courtesy of John Gallis Norseman Designs West

“My goal,” he says, “is to do something spectacular and hope I live long enough to get bored with that.”

His mentor and Oregon rodeo legend, the late Sterling Green, told him: “You can do anything,” says Gauteraux. It’s advice he’s taken to heart.

Gauteraux is refurbishing the 1890s building to include a second studio, a martini bar and lodging for future guests.

No Comments