04 Sep A Window to the Western Frontier

Urban renewal often equates demolition with progress, causing the old to disappear in favor of the new. This is why, in the rapidly changing heart and landscape of lower downtown Denver, Colorado, once home to streets of graceful 19th-century Victorian buildings, a lone survivor of a bygone era deserves special recognition. Neef Hall, built as a German brewery and dance hall circa 1878, stands fully restored as a cherished private retreat for a passionate collector who loves the Old West.

A Navajo weaving and original millwork frame the doorway to another time and place, just off the second-story landing of restored Neef Hall.

The homeowner isn’t just a savvy real estate investor. On the contrary, this three-story building, which houses an art gallery at street level and boasts a fully furnished interior throughout the upper floors, reflects his decades-long pursuit to preserve the structure’s original aesthetic. With a mix of purchased and custom-designed furniture and lighting, along with top-tier Western art, his goal was to create a comfortable 1800s-era getaway that stayed vigilant to a romantic vision.

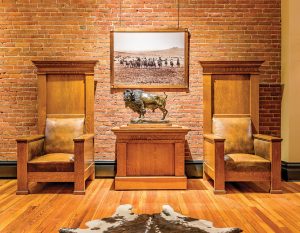

Vintage high-back chairs frame a bison sculpture by Robert Scriver and a 19th-century photograph by L.A. Huffman.

The building’s restoration reflects more than 30 years of refurbishment since its purchase in 1994, from the basement to the rooftop walkout. The homeowner updated the kitchen, exterior surfacing, lighting, wall coverings, security, and some other features. But the 11-inch-wide plank wood flooring, thick walls, windows, doors, moldings, and skylight are all original.

The dining room features a rich blend of materials, including brick, tin, pine, leather, and antler sheds. Genuine Arts and Crafts chairs surround the dining table.

The search for period-appropriate furnishings covered the Rocky Mountain West. Wooden high-back chairs in the living room came from a lodge that once belonged to the Knights of Pythias in rural Colorado. Arts-and-Crafts-era chairs, more than a century old with original leather upholstery, surround a pine dining table. A double antler chandelier was found in Jackson, Wyoming, while the custom-made circular steel chandelier bears 15 Charlie Russell bronzes and branding irons from La Veta, Colorado. The red, tan, and green color palette on floors, walls, and in textiles is historically correct.

A charming exterior graphic in the bedroom adds a touch of liveliness to the interior. The credenza, created by artist Mike Livingston, is adorned with carved busts of Native Americans.

In the bedroom, leather upholstered easy chairs are from Steel Strike, a Colorado business that specializes in Western reproduction furnishings. The arched, steel-frame bed was fabricated from Texas oil pipe and draped with a bison robe (tail intact) and an original Hudson Bay woolen blanket.

Throughout the home, the theme of bison prevails in sculptures, paintings, and even the owner’s logo. A focal point is the large bronze bull bison by sculptor Robert Scriver. Consideration for every acquisition was based on the item’s provenance, authenticity, and appropriate inclusion within the setting, evaluated by the owner’s trained eye.

A taxidermied longhorn hangs above an antique cast-iron stove. The armchair is upholstered in brindled hide and red buffalo check.

“I was raised in an artistic family where I learned to love beauty and look for it everywhere,” says the owner. “And I’m very particular.”

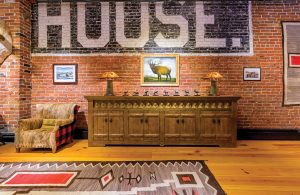

In the main gallery, or former dancehall, a large photograph by L.A. Huffman hangs above a leather settle from the Arts and Crafts period.

Pull up a chair “Old West style” in this informal gathering space. The hand-forged chandelier is embellished with rusted steel cattle brands and 15 sculptures by Charlie Russell.

A retired business executive and former cowboy, the homeowner was raised in the 1950s in the heart of California’s Western film and television industry. But this project is not a Hollywood stage set. Instead, it’s intended to reflect the spirit of an era and the honesty and simplicity of design back then.

The leafy Victorian wallcovering references the decorative style of the late 1800s. A walnut frame encircles the homeowner’s distinctive brand.

The porcelain washbasin and tureen and pitcher are antiques from the homeowner’s family.

Scale was another important consideration within the project’s design. After all, it’s not every day one fills a living space that’s 80 feet long by 25 feet wide, or a bedroom with 14-foot-high ceilings. Oversized sepia photos of cowboy life on the plains by photographer L.A. Huffman hang from picture rails as snapshots of the Western Frontier. Furniture arrangements were defined by purpose and scale: a dramatic, 10-foot-long credenza created by Kansas artist Mike Livingston, featuring a carved frieze of Native American faces, is a perfect example.

The home’s interior reflects the simplicity of design during the era. In the top-floor bedroom, a buffalo plaid sofa is a cheerful place for conversations.

The home’s exposed red sandstone brick walls add immeasurable texture and warmth. The owner removed by hand the original plaster and lathe that once covered the bricks — a labor of love richly rewarded. High on one wall in the bedroom, the lettering of a former clothing store, painted initially on an adjoining exterior wall, adds an interesting graphic to the mix and reflects the building’s purpose over time.

The leather chair is a reproduction piece from Steel Strike. A rare, antique Navajo rug softens the original brick wall.

In the primary bedroom, a bed made of steel oil pipes is covered in a wool Hudson Bay blanket and bison robe to echo the style popular in the late 1800s.

As one moves from the busy corner street entrance up the narrow stairway, stopping on the landing at the “ticket office” to the dance floor, and then to the bedroom on the uppermost level with its colorful bath and adjacent study, the journey isn’t so much about getting away from the city, as it is from the modern world itself. Here, visitors step back in time. The quiet soul of the building quickly surrounds and calms. The enveloping silence is a welcome balm amidst city chaos.

“I like to think of this place as my monastery,” says the owner. “A place of spiritual nourishment. I come here regularly on weekends and enjoy the quiet. Sometimes, I even entertain small groups; the main hall can hold as many as 100 people. But most of all, I like to slow down, maybe pick up a book, and contemplate 50 years of collecting.”

No Comments