01 Feb Native Outsider

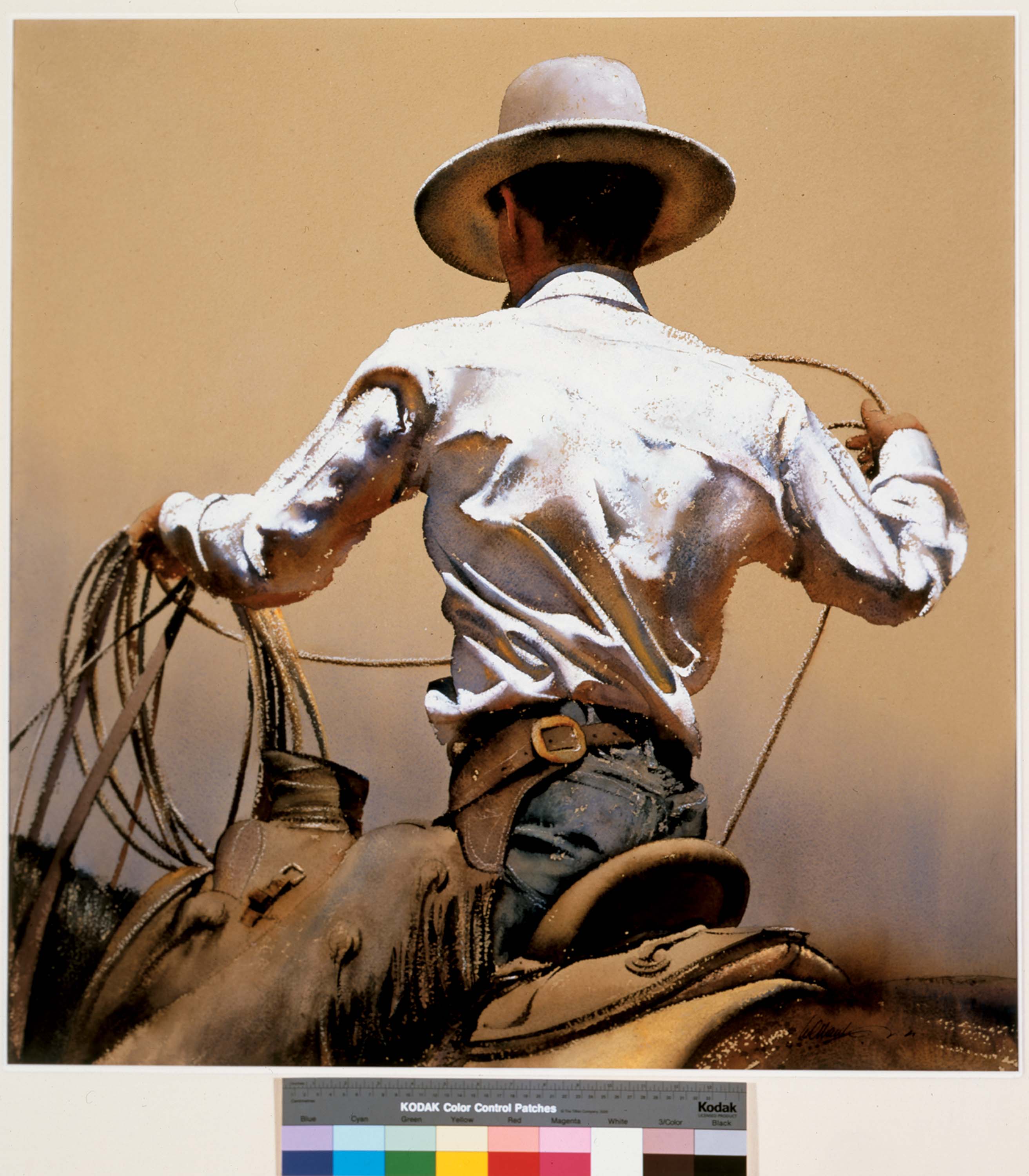

RINGSIDE IS A QUINTESSENTIAL WILLIAM MATTHEWS PAINTING, a large-format masterfully executed watercolor of a working cowboy, captured in a moment when an everyday task appears an act of grace. As is often the case with Matthews’ works, the subject’s face is not visible. Rather than simply being obscured by a lowered hat brim, though, the entire figure is facing away from the viewer. The cowboy, sitting deep in a well-worn stock saddle atop a bay horse, handles a lariat with practiced ease, intently focused on the livestock outside our view.

What’s striking about the painting, beyond technical mastery, is how little it shows in contrast to how much it says, and the extent to which the painter-observer’s expertise and authenticity conveys the subject’s expertise and authenticity. This is William Matthews’ gift, and Matthews — artist, musician, world traveler, collector — has purposefully developed this gift over a very dynamic and productive 40-year career.

Curator of American and European Art to 1950 and Art of the American West at the Phoenix Art Museum, Jerry N. Smith has known the artist for many years. “Ringside is a terrific example of Matthews’ work,” he says. “We see a figure, his back turned to us, atop a horse. He is working a rope with his hands, although we don’t get full detail of the action. It is the type of movement a skilled ranch hand would do without even thinking about the process. It is just part of what this person does in his daily routine. It is the quiet moment that appears effortless, which is why it works. Too often,” Smith continues, “paintings of cowboys are too staged, almost like film stills from an old movie. That isn’t the case with Matthews. The movements, the actions, the settings, every aspect of his figural works seems true and self-assured. This is why his paintings often appeal to those who claim not to like Western art. There is honesty in the work, in the report on what is being portrayed, that registers with people, whether they are familiar with ranch culture or not.”

Ranch culture — people, landscapes and architecture — are not his only subject matter; Matthews is an avid traveler who has lived in Europe and painted all over the world. But a major exhibition this winter at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), William Matthews: Trespassing, stands as a thrilling testament to his place in the West, as both native and observer. The show’s title is a nod to Matthews’ role as familiar outsider.

William Matthews is a Westerner. Though he was born in New York City, he was raised in San Francisco and has lived in Denver for decades. But, says the artist, “I’m not a cowboy; I didn’t grow up on a ranch. There’s always an element of feeling like I don’t really belong. I like the feeling that wherever I am there’s a sense of alienation. It lets my journalistic attitude kick in. I can see things in a more objective way; it’s not based on history. I always feel great excitement from discovering new places and letting my imagination run. The idea of Trespassing has to do with always being an outsider. I feel I come to painting, and to most places, as an outsider … and I like that.”

The exhibition, which opens with the poster created in 1973 for Matthews’ first one-man show, brings together approximately 65 paintings. It includes representative early work and progresses to a strong showing of recent pieces, including landscapes, rural architectural paintings and a series called Branding Arrangement, consisting of 35, 14-inch-square watercolors, vignettes from cattle brandings strikingly arranged in a grid. Matthews describes the exhibition as “a retrospective with a slant toward more progressive images.” Five paintings from DAM’s own collection, for instance, feature the same grain elevator painted at different times of the day and year.

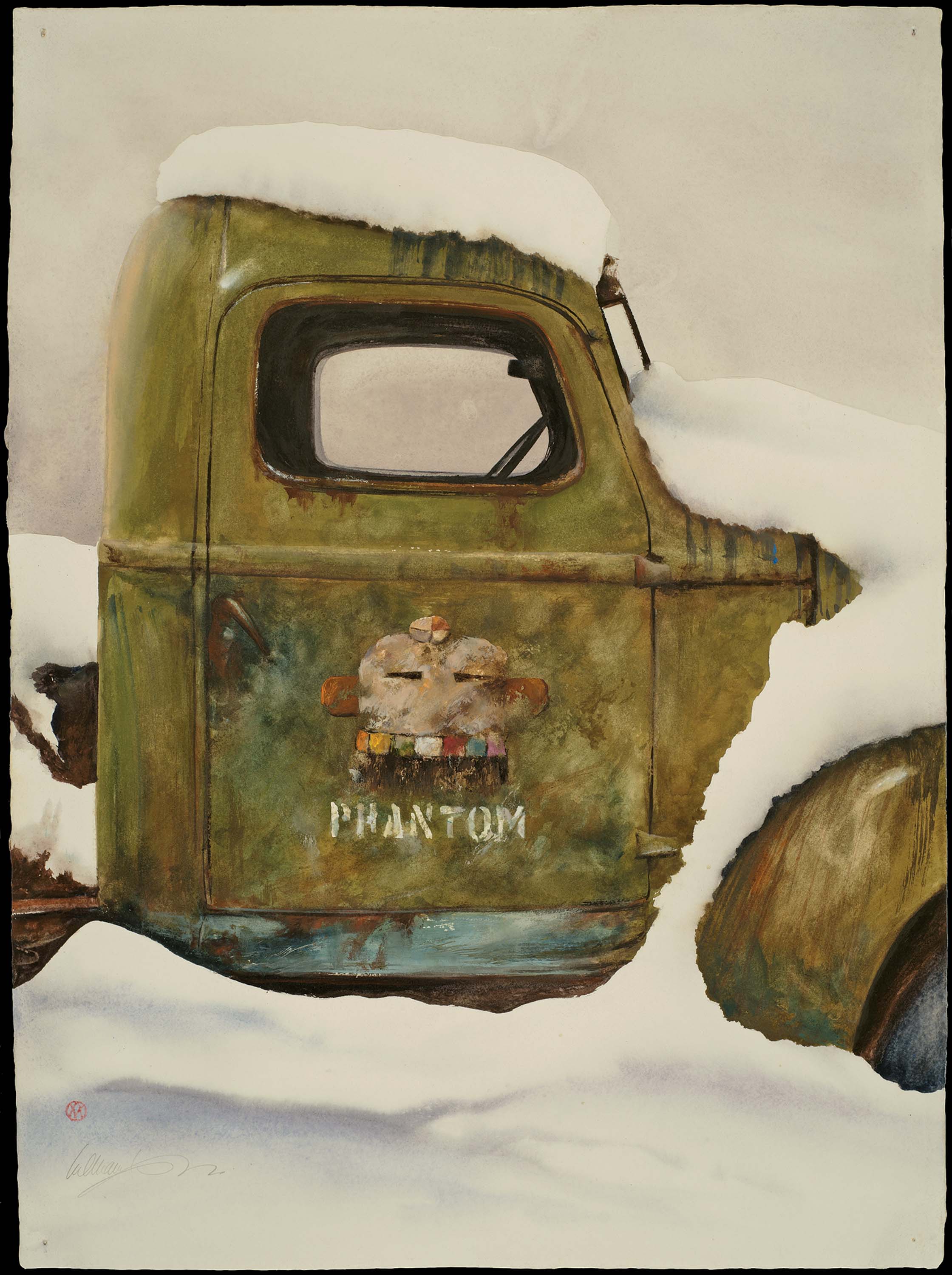

His industrial paintings, Matthews says, “are talking about the people, the land and landscapes, and the buildings. Architecture has always been an important part of what I do.” Hard Candy, on the other hand, depicts a seasoned cowhand, astride a horse, sucking on a lollipop (he was trying to quit smoking at the time), an ironic twist on the iconic image of the Marlboro Man. Matthews explains, “My interest has always been in pushing the boundaries and doing things that were quite different from what other people were doing.”

The exhibition was conceived by Thomas Brent Smith, curator of Western American art and director of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. Says Smith, “I thought, here’s an artist at a certain moment in his career who’s worked very diligently for decades. It felt like it was the right time to consider what he’d done over his career. One of the things I found interesting was that I could see that he was challenging himself. He would continue to make works challenging his notion of what the West is today. In the autumn of his career, it’s a chance to look back and to look forward as he continues to ask the question, ‘What kind of artist do I want to be?’”

In selecting works for the exhibition, Smith says he wanted to focus on Matthews’ Western works because “the West is where he lives; he has a deep regard and emotional attachment to it.” As far as scope, “We had quite a few conversations about what makes the most impact and what is the most interesting. We ended up trying to show the breadth and the range, showing key works from different periods in his career, but at the same time also showing recent work. It’s often not easy to do both, because it’s an approach with two different demands. But we were successful because the subjects harmonized.”

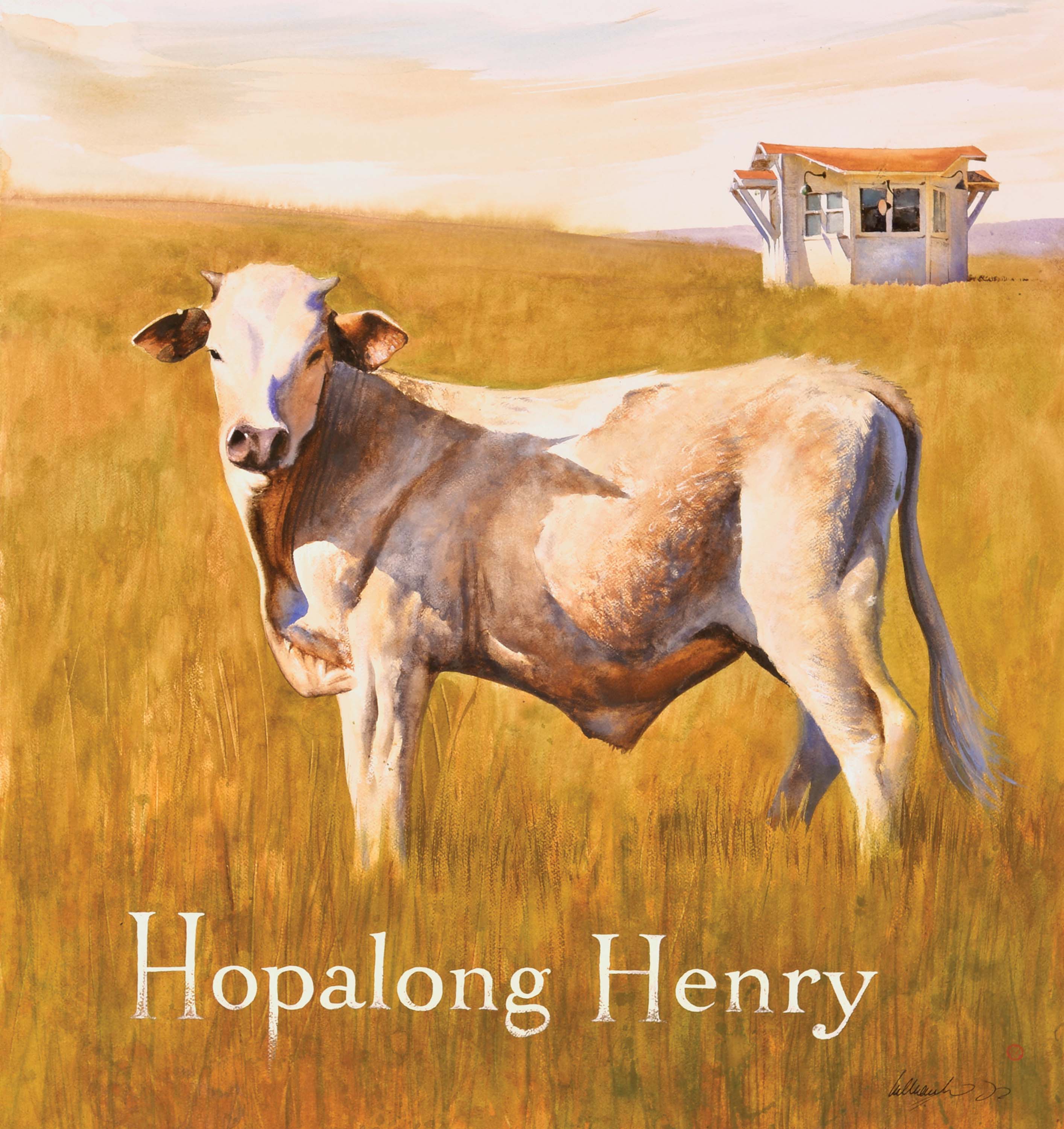

An anchor piece of the exhibit is a large and striking image of a white steer in an open landscape, a curious octagonal building in the distance. The work’s title, Hopalong Henry, is hand-lettered onto the painting. That painting and another called Californicopia incorporate graphic elements in a revisiting of Matthews’ early career as a graphic artist, when he designed album covers for Capitol Records and Warner Brothers. “I started going back to that a few years ago,” says Matthews, “playing with the idea of using language and using a word or words in a unified thought. I love words, I love language and I love typography; I’ve always been jealous of my musician friends and writer friends who can tell a complete story. I consider using words as part of my arsenal.”

“The type is somewhat new,” says the DAM’s Smith, “but plays to his strengths because of his years spent working on album covers and hand lettering, back before Photoshop. So he knows how to do this. But also he’s an artist who understands language and the importance of language and words, so it can be very successful for him.”

It’s an exciting time in the career of William Matthews; With 40 years of experience, he is at the peak of his maturity and productivity, and has clearly mastered an unforgiving medium. “With watercolor, you have to work quickly, yet sparingly — it is very easy to make a dark and muddied watercolor,” Jerry Smith explains. “Matthews provides just enough information without ever going into painstaking detail. The images are as much about a mood or feeling as they are the given subject matter. Matthews is one of the real exceptional watercolorists working today.”

In addition, Matthews is the subject of a new documentary film, “William Matthews: Drawn to Paint,” by Amie Knox, who teasingly describes him as “a masterful watercolor painter, globe-traveler, passionate collector of friends, generous participant in life and occasional screw-up.” Knox, who has made many films documenting the artistic process, explains she had watched Matthews paint and felt his work needed to be shared with a larger audience. “Willy’s great gift,” she says, “is that not only can he capture the particular spirit of a place with a minimalist’s eye, but that he forms intensely human connections with many of his most evocative characters and subjects.”

Sue Simpson Gallagher, who has represented William Matthews for 20 years, says intellectual curiosity is the key to understanding this painter. “Willy Matthews is a man of the world,” she says. “He is curious about everything. He is a good listener. He is a great storyteller. Whether he is painting a camel in Egypt, a castle in Scotland, a cowboy poet in Nevada or a grain elevator in Montana, Willy imbues his subject with emotion. Through his medium and his masterful brushwork he is able to convey the feeling of a person and of a place. Although best known as a painter of cowboys and the life of the cowboy, it is his fellow humans and the lives they live, that are Willy’s subjects and his passion. Willy has so much soul, and it is in everything he creates.”

For this constantly evolving artist, it’s very simple. “It’s always about ideas,” he says. “It’s always about processing things in a new way, and discovering new worlds. I’m still learning where the paintings are, when to start them and, more importantly, when to stop.”

- “Hopalong Henry” | Watercolor | 33 x 36 inches (click to enlarge view)

- “Bottle Taps” | Watercolor | 21.75 x 31 inches

- “Ghosts of Nebraska” | Watercolor | 29.25 x 24.25 inches

No Comments