11 Mar Collector’s Notebook: Preserving Fine Wine

You don’t have to live in California to know that America’s love affair with wine has blossomed into a serious relationship. We drank 805 million gallons of it in 2018, according to the Wine Institute of America, more than we’ve consumed in any year since the Institute began keeping tabs in 1940.

As much as we might imagine otherwise, we are not like the French in our vin habits. Americans think about wine differently. Few of us buy cases in our children’s birth years, for example, and allow it to age alongside them. And some 90 percent of Americans drink a bottle of wine within a week or two of purchase, according to a 2018 survey by the Wine Business Institute at Sonoma State University.

Yet, as we fall increasingly into the grip of the grape, the inclination to drink our wine sooner, and not keep it for a future pairing, might be on the cusp of change. Designers who specialize in custom wine cellars are receiving more requests for their services. Those who want abundant opportunities to enjoy a special bottle are building cellars for their “liquid poetry,” as Galileo described it, so they will remain lyrical until their time comes.

“If it’s a handful of bottles that one simply wants to keep reasonably well,” says Jon Maxwell with Veritas Wine Consulting based in Bozeman, Montana, “a cool bottom cabinet, the floor of a closet, or a temperate corner in the basement will be an improvement over the kitchen counter, and it will very likely do the trick, as long as it won’t be kept there for more than a few months.”

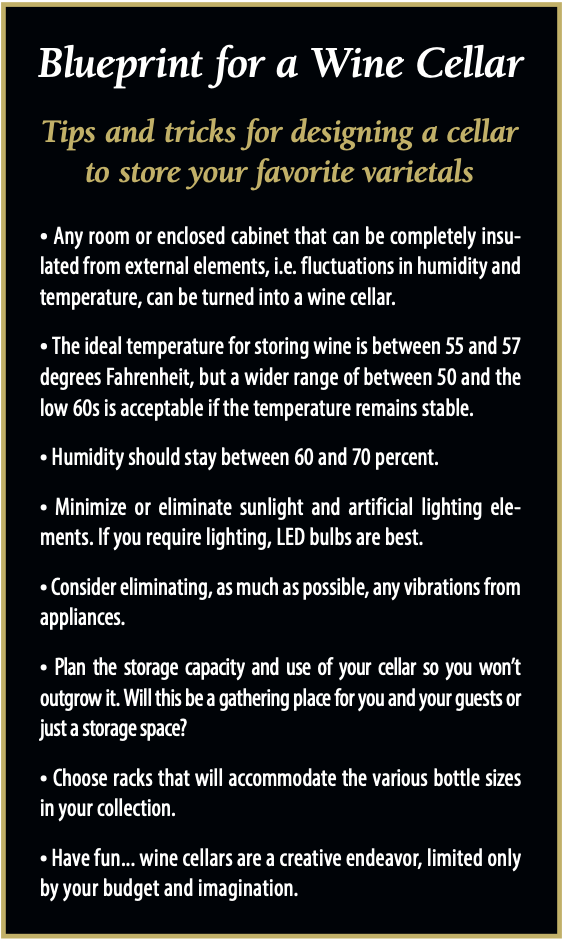

But if you want to keep wines for an extended period, he says, to experience the evolution of age-worthy bottles over the years or house a collection, you need a contained space in which temperature, humidity, light, and vibration are controlled. You can begin with a refrigerator — like a cabinet cellar that’s moveable, affordable, and will hold 200 or more bottles in a pantry or vestibule. The burgeoning collector may opt to design a wine cellar with the aid of a company like Vigilant, which provides remote design assistance along with cabinetry, furnishings, and fixtures specific to wine cellars. The more advanced oenophile may call in a specialist. Thomas Warner Wine Cellars in Novato, California, and Charles River Wine Cellars in Boston, Massachusetts, for example, customize cellars to meet their clients’ unique tastes and lifestyles.

But if you want to keep wines for an extended period, he says, to experience the evolution of age-worthy bottles over the years or house a collection, you need a contained space in which temperature, humidity, light, and vibration are controlled. You can begin with a refrigerator — like a cabinet cellar that’s moveable, affordable, and will hold 200 or more bottles in a pantry or vestibule. The burgeoning collector may opt to design a wine cellar with the aid of a company like Vigilant, which provides remote design assistance along with cabinetry, furnishings, and fixtures specific to wine cellars. The more advanced oenophile may call in a specialist. Thomas Warner Wine Cellars in Novato, California, and Charles River Wine Cellars in Boston, Massachusetts, for example, customize cellars to meet their clients’ unique tastes and lifestyles.

However lavish or restrained your wine cellar aspirations, getting it right is all about physics and controlling those four properties: temperature, humidity, light, and vibration.

The ideal temperature for long-term wine storage is 55 to 57 degrees Fahrenheit. Although a range of between 50 and the low 60s is fine, the important factor is that the temperature remains stable and consistent, Maxwell says. Though most cellars in the U.S. rely on artificial climate control systems, passive cellars, like the one Santa Barbara architect Clay Tedeschi fashioned out of his subterranean boiler room, will also work.

For years, Tedeschi and his partner Lewis enjoyed throwing dinner parties in their rambling Montecito home. Pairing a great wine with Lewis’ elaborate menus was part of the fun. The concrete walls of their boiler room and 14 inches of soil over the ceiling kept the temperature between 55 and 63 degrees year round. All he had to do was remove the 1920s era cistern, give it a new floor, a coat of paint, and install racks. And even though the humidity must be controlled in a wine cellar, Tedeschi did not give his boiler room/wine cellar a vapor barrier until much later. He and Lewis were not wine collectors and didn’t view their stash as an investment.

When Lewis was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2003, Tedeschi took on the role of primary caregiver. He didn’t have time to think about a glass of vino on the deck at sundown. His wine stash below ground was all but forgotten. In 2017, four years after Lewis passed away, Tedeschi decided to give the cellar an upgrade. But first, he had to face 1,000 bottles of white wine that, having sat for 14 years in an overly humid cellar, were no longer drinkable.

For this custom wine cellar, designed and built by Thomas Warner Wine Cellars, solid oak racks with a medium walnut stain display a Wisconsin-based wine collector’s stash of First Growth Bordeaux and cabernet. Green granite countertops, a mix of waterfall displays, and storage bins complement the home’s Craftsman-style architecture.

Humidity should range between 60 and 70 percent in a wine cellar, says Maxwell. Below 50 percent could allow your corks to dry out and oxygen to seep in, damaging the wine. Humidity over 70 percent is an invitation to moldy, illegible labels. This is another problem Tedeschi faced when he returned to his cellar after the 14-year absence; he was only able to save a few bottles with readable labels.

Fortunately, an artificial climate control system will manage both temperature and humidity in a wine cellar, but the walls will need a vapor barrier, along with insulation, installed first. “You need to isolate the space so that you can use a mechanical cooling system and create an environment for the wine,” says cellar specialist Thomas Warner.

Wine also needs protection from the sun’s UV rays, which will inflict damage over time. Darkness is the best choice when no one is there, but if you need your cellar to be lit all the time, use cooler LED bulbs.

It’s also beneficial to think about the rumble of nearby appliances injecting vibration into your cellar. “There is some theorizing that even very small amounts of ongoing vibration can speed up the aging of wine,” says Maxwell. “And any significant shaking can certainly disturb sediment that may naturally form in a wine as it ages.”

For the wine itself, the essential preservation elements will always be hidden behind the walls, primarily the insulation and vapor barriers. But for the people enjoying the wine, the important elements are less technical and more aesthetic, Warner says. There’s the choice of wood or stone, whether the racks are metal or wood, and if the space will be used for storage or incorporate a tasting area.

When Tedeschi updated his cellar in 2017, he raised the ceiling from 6 feet, 2 inches to 7 feet, 6 inches, painted the concrete walls black, and applied a vapor barrier. A new climate control system now keeps the temperature and humidity in the sweet spot, protecting his 850-bottle collection, all of which rest in vintage viewing racks above a colorful Oriental rug. Tedeschi’s favorites, his collection of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, are arranged together on the far-facing wall. Made in and around the village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, in France’s Rhône Valley, and bottled in heavy dark glass, the ornate labels still bare the ancient papal insignia that harkens back to the wine’s 14th-century origins. Facing the center of the room, every bottle is a small siren, calling you to come closer, to inspect, maybe even to sip.

No Comments