11 Mar John Alexander

DESPITE HAVING LIVED THE PAST FOUR DECADES in New York, John Alexander (b. 1945) still speaks with the gentle, rolling cadence of a well-heeled Southerner as he tells stories of his father, and of growing up in Beaumont, Texas. He recalls camping and fishing the bayous and swamps, of how, in lieu of museums, nature taught him to read the nuances of the land with its sounds and smells — because, really, how can you paint the land if you don’t know it intimately?

And so, when Alexander tells you he doesn’t paint the South as a tourist, but as a person who has inhabited it, you know this is true. That truth, informed by love, respect, and concern for the flora and fauna that we say we revere and yet somehow fail to protect, is folded into every work of art he creates.

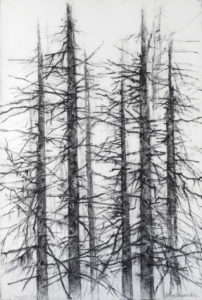

Ghost Trees | Charcoal on Paper | 60 x 40 inches | 2019

It’s been said of Alexander that he “paints nature at its grandest and man at his worst.” To this end, his work can be deceiving: a gorgeous, moody canvas of wetlands or vines and flowers will catch your eye from across the room, but as you approach, subtleties begin to surface; small details softly sing a deeper harmony to a story unfolding before you.

“You have to use both sides of your brain,” Alexander says of his artistic intentions. “I do work outdoors and from nature. These are not just fantasy worlds, they’re from the natural world. But I’m very conscious of and sensitive to environmental concerns, so much of my political concern is about nature. A lot of urban artists don’t have the same sensitivity.”

em>Monkeys in the Garden | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 50 inches | 2019

Place and politics in Alexander’s work are most often expressed in grand dimensions, starting at 5 feet. In so doing, birds, plants, and animals are portrayed life-sized, which has the dizzying effect of pulling you in. It’s as if you are embedded in his fantastical reality, floating through lily ponds or climbing along gnarly branches laden with egrets or monkeys. You might find yourself lost in a field of cotton plants, their ripe bolls rising to the heavens like an offering of faith, forgiveness, or remembrance; or you could be sailing on turbulent seas, gazing at a cast of imbeciles watching helplessly as their craft keels and takes on water. What to do? Laugh? Cry? Alexander seems to suggest that it’s your choice; just feel something.

When he bought property in Amagansett, New York, for his home and studio — two barns built in the 1700s that he gently restored to keep the original aesthetics of the

structures — he set to work on the pond. Situated just right, he brought in regional vegetation and tended to it so that, at this point, it’s as though he’s nurtured part of his youth into the modern world. “It took a number of years to get it to look like it does now,” Alexander says. “It’s really taken off in the last 20 years. It’s gotten so overgrown that I have to clean it out from time to time. Even though I’ve spent the last 40 years in a loft in New York, I manage to paint like I live in the Texas swamps. I’ve spent a lot of money making my pond in Amagansett look like a Texas lake by planting water lilies and cattails.”

Blue Point | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 48 inches | 2019

Nature, Alexander believes, is the greatest teacher for artists. After 52 years behind the easel as a professional artist — a number that started ticking upward the day he graduated college — he is still finding inspiration in the land. He often travels, drawing wherever he goes, gathering ideas and material for his next series of paintings.

He has gone to some impressive lengths in his quest for not only subject matter but also emotional content. Take, for example, the past two summers when he was painting in a dead cypress forest on a friend’s property in Maine. “The caretaker,” he recalls, “built me a wall out of plywood, 5-feet-high, about 40-inches wide, in the middle of a forest near a pond. In the pond, there are all these dead trees sticking out. The insects were incredible. I had to put a net up because of the black flies. You can picture me drawing dead trees while being eaten by insects.”

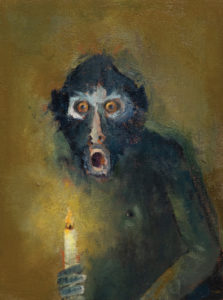

The Prophet | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 9 inches | 2019

Another time, in his own take on the famous tale of J.M.W. Turner strapping himself to the mast of a ship in a nocturnal snow squall to understand meteorological changes in the weather, Alexander decided to capture the savage churning of the ocean in a storm by strapping his easel to the side of a friend’s cinder block recording studio during a hurricane. “It was exciting and a lot of fun,” he says. “The raw emotional power you can get from nature by being in nature. You know when the barometric pressure drops, people feel it. There’s a reason people get excited during big storms; you get a sense of euphoria.” He’s also opened the barn doors of his studio while nor’easters blow through so he can capture the raw force of nature.

“Turner was one of my great influences,” Alexander says. “Also, Goya. Goya’s paintings took on a very dark turn at certain times in his life. I used to base my satirical paintings on humor, skewing hypocrisy and greed, but now it’s more serious; I’m very worried about our world, especially because of how much I love animals and birds. We have a president who has eviscerated preservation. Everything that has been worked on for decades he did away with in one sweep of the pen, boom. Anyone who has the slightest love of wildlife, flora, and fauna, has to be horrified.”

Lilies in the Headlights | Oil on Canvas | 70 x 60 inches | 2019

And though it may seem like his work, so deeply rooted in his Southern upbringing and political message, might be considered niche, he has instead managed to bridge geographic distances. For in his subtle way of calling attention to our uncertain environmental future, he always manages to imbue a feeling of hope.

“All of his art has interesting undercurrents and narratives,” says Maya Frodeman, gallery director at Tayloe Piggott Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “His work commands attention in a unique way; it’s very Goya-esque.”

Plus, many of the gallery’s collectors already knew his work. In fact, it was a long-time collector who initially called Alexander to their attention. “The first time I saw his work, I was taken by his ability to handle light and create luminescence,” Frodeman says. “I think that’s what people really respond to: the light.”

Opposites Attract | Oil on Canvas | 11.5 x 11.5 inches | 2019

Over the years, Alexander’s work has been widely exhibited in museums, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. His paintings belong in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, among others. In the spring of 2021, a retrospective of his work will appear at the McClain Gallery in Houston, Texas. Coupled with a book, the exhibition is a major undertaking that will require borrowing early works from museums and collectors. “It will be a ‘then and now’ kind of show,” Alexander says. “I really do want those ’70s pictures to be seen again. No one knows what they look like.”

Whether glancing back to his past or searching into the future, Alexander hopes his work makes people think, to be more aware of the natural world, and to discover a new way of seeing. “I would hope my landscapes have my own personal feeling so that people wonder: What is John saying? What is he trying to tell me? I’m content if I’ve made people think. Art is not about decoration and glitter,” he says. “I’m interested in soul searching.”

No Comments