11 Mar Perspective: Grandma Moses [1860–1961]

In the years following World War II and into the Cold War era, an edge of existential uncertainty clouded the collective American mind in a way that it hadn’t before. Then along came a sprightly, witty, self-assured but humble old lady who painted cheerful scenes of rural America from an earlier, much simpler time. There were beautiful rolling hills and farms, white in winter and brightly colored the rest of the year. There were country folks working and playing together, putting their hands to farm chores, quilting bees, and communal meals. It was a seemingly uncomplicated world of predictable cycles and seasons, with family and community acting as a comforting, familiar context for daily life — and it found deep resonance among the American public.

Grandma Moses painting in the room behind her kitchen | Photograph by Ifor Thomas | 1952 | ©Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York

The self-taught painter who created these scenes, known as Grandma Moses, appeared as simple and familiar as her art. Her imagery became enormously popular beginning in 1940, and so did Moses herself. Magazines, television, occasional in-person appearances, and her 1952 autobiography helped make her a celebrity art star. Yet, she remained unchanged by fame. Until her death at age 101 in 1961, she was unassuming and quaintly charming, as down-to-earth as the decades of farm life that inspired her paintings.

“Grandma Moses’ underlying theme was always that hard work and reward go hand-in-hand,” notes Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C. Since the late 1990s, Umberger has employed research, writing, and exhibitions to elevate and expand overarching historical narratives involving figures, such as Moses, who navigated autonomous artistic paths. SAAM is currently preparing a major exhibition on Grandma Moses’ life and art to open within the next few years. Galerie St. Etienne in New York City, which has represented the artist since 1940 when it hosted her first solo show, donated several masterpieces to SAAM, which will feature prominently in the exhibition.

Hoosick River Winter | Oil on Pressed Wood | 18 x 24 inches | 1952 Kallir 1031. Private Collection | ©Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York

No one could have predicted the trajectory of the girl born Anna Mary Robertson in 1860 near Easton, New York. One of 10 children of Margaret Shanahan and Russell King Robertson, a flax mill operator and farmer, Anna Mary had very little formal education. She helped her parents and siblings while she was growing up and left home at 12 to work as a hired girl on a neighboring farm. But while chores filled her days, she was always artistically inclined. As a child, she was inspired by her father, who once painted landscapes on the walls of their family home. He encouraged her interest by bringing home paper and colored chalk, a treat he considered a better value than candy because it lasted longer.

Anna Mary spent 15 years working for other farm households, and at one of these she met “hired man” Thomas Salmon Moses, who became her husband. The couple moved to Staunton in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and worked on other farms before attaining their own. Moses had 10 children, five of whom survived infancy. In 1905 the family settled on a farm near Eagle Bridge, New York, where she remained the rest of her long life.

While the demands of farm life and motherhood left no time for artistic pursuits, creativity was always part of Moses’ world. She quilted, used house paint to decorate a wooden fireplace screen, and made embroidered yarn pictures for family and friends. As age brought arthritis to her hands, embroidery became painful. When she was in her 70s, her sister suggested that painting might be more comfortable. Moses tried it, and thus began her artistic career.

In 1938, an art collector named Louis J. Caldor noticed several small paintings by Moses in the window of a drugstore in Hoosick Falls, New York. He bought them, and then others at the artist’s home, for $3 to $5 each. The following year, three of her paintings were included in an exhibition titled Contemporary Unknown American Painters at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In October 1940, Galerie St. Etienne’s founder and owner, Otto Kallir, hosted the gallery’s first solo show for Moses, who gained the nickname Grandma Moses from a reviewer in a New York newspaper.

At Thanksgiving of that year, dozens of Moses’ paintings were exhibited at Gimbels Department Store. At age 80, Moses traveled to New York City for the second time in her life to attend the show and talk with the public. The experience inspired the 1946 painting Grandma Moses Goes to the Big City, which depicts the artist in a black dress preparing to leave the farm for the trip. Among the largest of her works, at roughly 36 by 48 inches, it is a “memory painting of herself at the crossroads of farm and fame, when her horizons expanded both literally and figuratively,” Umberger says.

With no access to fine art supplies, Moses’ first paintings were created with materials found around the farm: house paint on cardboard or wood, and even an old piece of canvas that once covered a threshing machine. Throughout her career, she continued to use flat white house paint as an undercoat. Caldor presented her with her first set of artist’s paints, and after she began her affiliation with Kallir, his secretary, Hildegard Bachert, would take along art supplies whenever she visited the artist.

Initially, Moses copied compositions she saw in greeting cards and calendar prints. Later, she developed a practice of clipping magazine pictures and tracing their vignettes of people doing things. She abstracted these figures and positioned them in her compositions. She then filled in the canvas with landscapes painted from memory or life. Although Moses learned to paint on her own, Umberger doesn’t describe her as a folk artist. “She found her own style in her own way; she didn’t learn through a handed-down tradition or craft, but she did work in a landscape tradition,” she says.

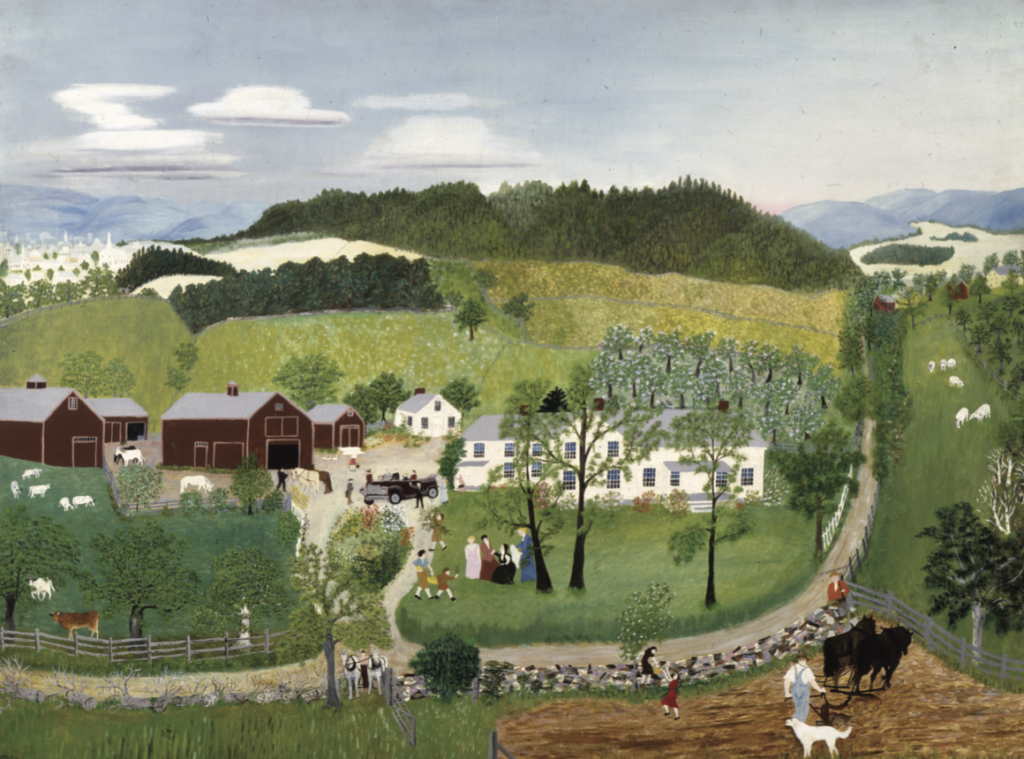

Grandma Moses Goes to the Big City | Oil on Canvas | 36.75 x 48 inches | 1946 | Kallir 577 | ©Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York | Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Kallir Family in memory of Otto Kallir

Reflecting deep contentment with the world she had known since birth, Moses intentionally omitted telephone poles and other signs of modernity, focusing on the bonds among people and between people and the land. “Her subject was an idealized American past, but it wasn’t illustrative — as in illustration — because the figures were abstracted. Instead, they become generalized, allegorical ciphers, connected to the past but living in the present, not confined to the past,” says Jane Kallir, an art historian, the current director of Galerie St. Etienne, and the author of Grandma Moses: The Artist Behind the Myth, among other books. As Otto Kallir’s granddaughter, she “grew up with Grandma Moses,” as she puts it, during the height of the artist’s fame in the 1950s and ’60s.

The double appeal of Moses’ public persona and accessible, buoyant art made her seem to be everywhere in those years. Kallir remembers seeing Grandma Moses paintings in the gallery and on greeting cards and calendars. In 1955, legendary television journalist Edward R. Murrow interviewed Moses as a guest on his TV show. When she turned 100 in September 1960, she was featured on the cover of LIFE magazine. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller proclaimed her 100th birthday “Grandma Moses Day.” Even when she met with President Harry S. Truman, the topics of conversation included cows, Kallir says. “It didn’t matter who she was with; she simply was who she was.”

Yet, the same personal and artistic qualities that fueled Grandma Moses’ broad popularity — at a time when many Americans were put off by cutting-edge modern art — worked against her among the art world elite. In that realm, not only was she a woman in a male-dominated field, but populism was anathema to what was considered serious art. “The fact that she was an old lady was a double-edged sword. She was innocuous, cute, funny, not threatening to men, but those are also qualities that could be held against her as a serious artist,” Kallir says.

Indeed, it wasn’t until Kallir began working at her grandfather’s gallery in the late 1970s, after graduating from Brown University, that she began to understand the level of artistic talent behind Grandma Moses’ work. Otto Kallir wanted high-quality, detailed photography of the paintings, and his granddaughter had studied photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. She set up strong, angled lighting to capture the texture and used a close-up lens. “For the first time, I was really looking at these paintings and realizing how brilliantly they were crafted,” she says. “Each little detail is equivalent to a painting, but the totality and the way they meld together to make a cohesive composition makes them all the more impressive.”

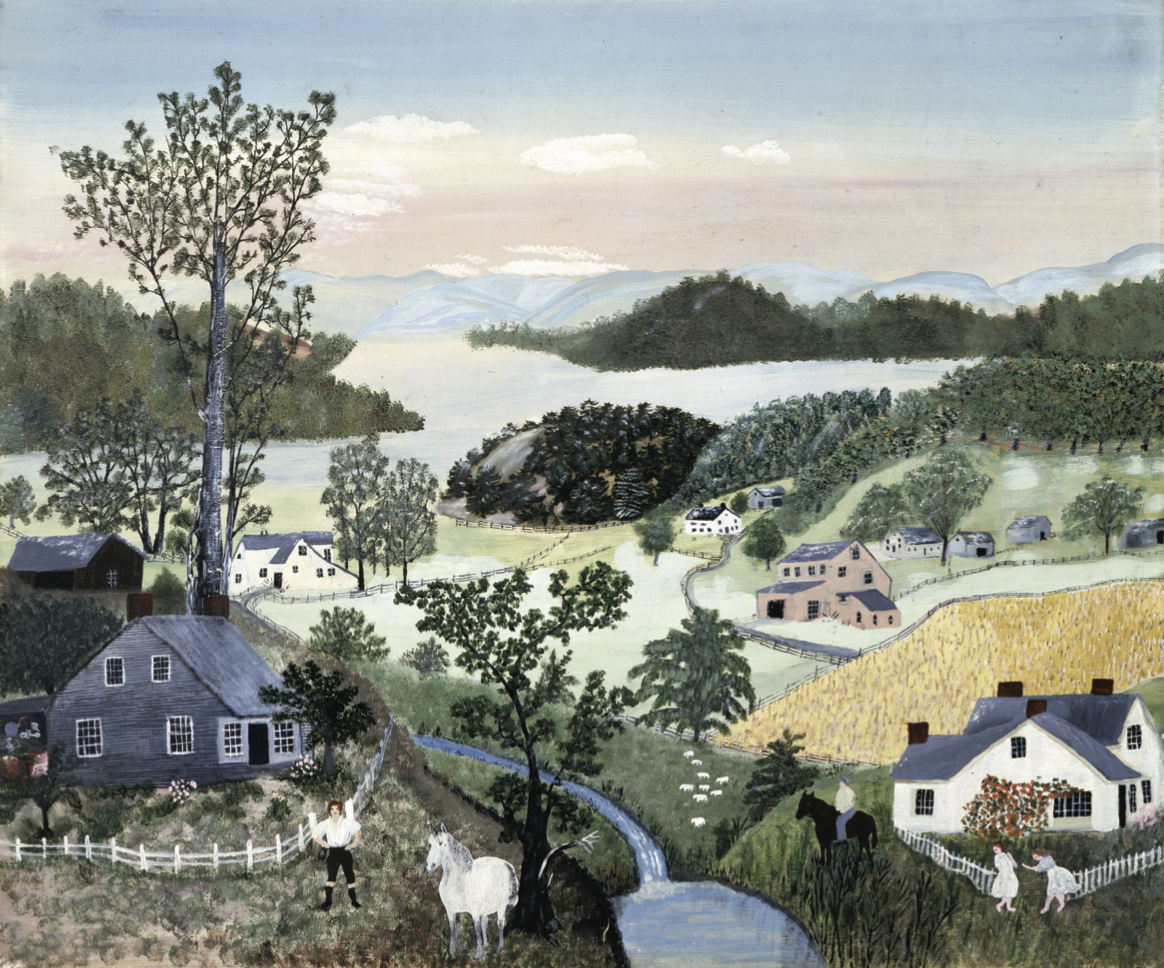

Among Kallir’s favorite Grandma Moses paintings is A Beautiful World, a summer scene that evokes many of the traits epitomizing the artist’s work. “It’s such a scene of bucolic harmony, and it represents her feeling of unity with nature — that human and natural activity were part of one whole,” Kallir says. “Her use of color in this is exceptionally beautiful.” Both of these qualities, Moses’ style and her underlying positive message, contributed to her influence on children’s book illustration, especially during her lifetime.

After her death, the cult of personality surrounding her declined. In the decades since then, however, curators and art historians have taken a closer and more appreciative look at the work she left behind and her place in American art. “It’s very interesting,” Kallir says. “When you take a simple, old, painting grandmother and start to unpack everything her legacy contains, it’s surprising how complicated her story was and also how great her art is.”

No Comments