15 Mar Meditations on Mortality

Painter Thomas Aquinas Daly expresses the exquisite beauty of living through the lens of death. Echoing the work of 16th- and 17th-century Dutch vanitas still life painters, whose main concerns were mortality, the transience of human existence, and the futility of materialism, Daly also points to nature’s bounty as an affirmation of life.

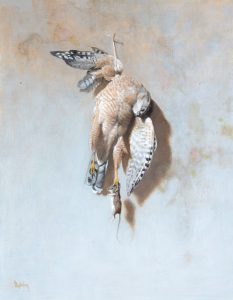

Still Life with Sharp Shinned Hawk and Deer Mouse | Oil on Board | 17.5 x 14 inches | 2019

“If you look outside, like [at] the birds at the feeder, that’s life,” Daly says. “But death is everywhere in nature.” For example, Daly and his wife saw a crippled blue jay that could not fly into a tree. “We were watching him, talking about going out and helping him, when a great big red-tailed hawk swooped in and grabbed him. That’s what happens. Understanding that makes life a lot easier for me to handle.”

The still life genre is long-lived, dating to first-century Roman frescos. However, the most easily relatable works are by Dutch artists who sold their oil paintings to the merchant class, a group of flourishing businessmen struggling with flaunting their wealth while remaining pious to their Protestant faith. These vanitas paintings portrayed such subjects as overflowing bowls of ripe fruit, peeled lemons, cheese, and plates seemingly abandoned after satiating guests. They almost always include a reference to time, with clocks, watches, or merely an extinguished candle. These works represent a middle ground — showing off an exotic table while acknowledging mortality.

Oriole and Chicory | Oil on Board | 14 x 11 inches | 2019

For Daly, his still life paintings conjure early morning hunts, a walk in the woods, or drinking from a thermos on a fall afternoon while waiting in a deer stand. The pieces are inherently quiet and almost spiritual, especially considering the contemplative backgrounds he incorporates.

“Killing a duck, picking it up, it’s warm, and it’s tactile,” Daly says. “I killed it and there’s no remorse. I like the hunt, and I do kill, and I do appreciate the animal. Especially as an artist, I see what it looks like; I get excited about the feathers and shapes.”

Muskrat Ramble | Watercolor | 12 x 17 inches | 2019

When thinking of a new painting, Daly goes through the collection of photographs he’s taken. “Then I go over all kinds of books; something has to knock me out,” he says. “When I do start painting, I am very aware of the flat surface … all I have is two dimensions, so the idea is to break up space in an interesting way to catch someone’s eye, especially from a distance.”

In considering a composition, he looks at shapes that draw the viewer’s eye to the still life. But he also likes to position objects in his studio in such a way that they create intriguing shadows. “I have a small window in my studio that breaks up the space in a painting,” he says. “The cast shadow, in addition to the shape itself, creates interest. The wall is smudged. Sometimes, I put a piece of torn wallpaper on the wall, and then I conceive of different backgrounds or think of a paint color I want in it.” The background contributes an abstract quality and stands in contrast to the realism of his still life subjects.

A Winter Landscape on a Full Moon | Oil on Board | 14 x 20 inches | 2018

Peter Stremmel, executive director of Stremmel Gallery in Reno, Nevada, started showing Daly’s work in the 1980s. “What I like about him most is that he is authentic. He doesn’t worry about what’s happening in New York or even in his own market,” he says. “He paints the life he lives, and lives the life he paints. He’s an outdoorsman who hunts, fishes, traps, and paints. … I always felt there was something about him that set him apart. Because he is so unaffected by the art world. He’s true to his art.”

Stremmel sees an influence of other historical painters in the way Daly paints with luminosity and his approach to the subject of a long-standing genre. “Daly’s paintings are very moody but also formal in their approach,” he says. “They shouldn’t just be looked at as dead fowl hanging. It’s part of being a hunter, and it’s how we as humans nourish ourselves.”

Still Life with Roses, Vase, and a Paper Moon | Oil on Board | 12 x 14.875 inches | 2018

And at the same time, he also finds Daly’s work reaching for something bigger than himself. “Some of the paintings remind me of Edward Hopper, with that feeling of isolation, a kind of spiritual quality … and a sense of awe for nature; even some of the simplest compositions are so powerful. They’re very compelling. I’ve got a couple of his pieces in my house, and they never cease to intrigue me and create a sense of wonderment.”

Michelle Dickson, the director of programs and events at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, also celebrates Daly’s artistry. “I oversee Western Visions, the largest fundraiser we have, and [am] constantly seeking the highest caliber of artists to participate,” she says. “Thomas Daly is certainly one of those treasures.”

The Winding Stream | Oil on Board | 18 x 24 inches | 2020

Dickson views the longevity of his career — he’s currently 85 years old — and the timelessness of his work as a priceless addition to the museum’s cadre of artists. She also notes that in 2021, he was selected for Western Visions’ Reid Smith Award, or artists’ choice award. “That speaks volumes about the quality of his work, as this is an award from his peers,” she says. “That is a pretty great honor.”

A perfect example of Daly’s soft, ethereal style is his painting Still Life with Roses, Vase, and a Paper Moon. In the work, Daly positions two roses, one white and one pink, in a porcelain vase set off by a round, thumbtacked paper cut-out. The flowers, just about to drop a petal, are fully opened and vulnerable to each passing minute, bringing a somber beauty that asks the viewer to take a breath, to slow down.

Daly’s paintings entice the viewer to pause for this kind of quiet discovery, and they reward the patient observer with a deeper understanding of life and even death.

No Comments