15 Mar Perspective: The Dean of Western Artists

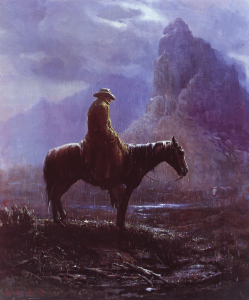

John Wayne stood looking at a painting by Olaf Wieghorst, an artist he knew and admired and whose work he collected. The painting, Spring Rain, is a night scene depicting a mounted cowboy in the rain, water running off his hat, coat, and his drenched but patient horse. The actor turned to Wieghorst and declared, “Olaf, this is the wettest picture I have ever seen!”

Spring Rain | Limited Edition Print: Lithograph | 23.5 x 19.5 inches | 1987

The painting held memories of first-hand experiences for Wieghorst, who spent much of his long life on horseback — as an army cavalryman along the Mexican border during the time of Pancho Villa, a working cowboy in Arizona in the early 1920s, a trick rider, and a mounted policeman in New York City.

He was also among the best-known and respected Western painters of his time, often mentioned alongside Frederic Remington and Charlie Russell. Four presidents — Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — hung Wieghorst’s art in the Oval Office. He appeared in two of John Wayne’s movies and enjoyed friendships with other Hollywood figures, including Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Clint Eastwood.

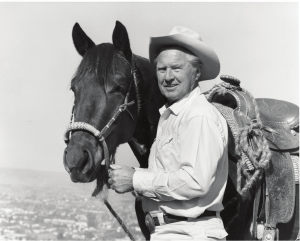

Olaf and Spooks | Photo: Roy Wieghorst

It was all far beyond what young Olaf could have imagined growing up in Denmark, learning to ride horses and reading cowboy dime novels about his heroes in the American West. “He always wanted to be a cowboy,” says Jim Daniels, president of the Wieghorst Museum and Western Heritage Center in El Cajon, California.

Born in 1899 in the Danish village of Viborg, Wieghorst was introduced early on to both horses and art by his father Karl, a photo retoucher, display artist, and fitness enthusiast. When Olaf was 3, his father began teaching him acrobatics, including handstands and trapeze rings. By 9, Olaf was performing at a Copenhagen theater as “Little Olaf, the Miniature Acrobat.” As a young teen, by then too big to be called miniature, he took a job on a stock farm, further honing his horsemanship skills. Meanwhile, his father encouraged his interest in drawing and painting, which Olaf continued throughout his life, regardless of whatever else he was doing.

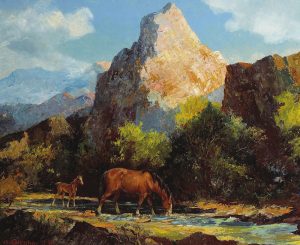

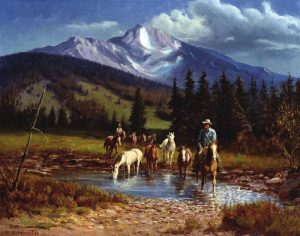

Mountain Creek | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 36 inches | 1950 | Collection of Jim Drye

At 19, determined to see the American West, he signed on with the crew of a Danish steamship. Upon arrival in New York City, speaking no English but with the address of his mother’s sister, he jumped ship. He rode the subway for three days, searching, until he ran into a soldier who spoke Danish and drew him a map. Wieghorst’s aunt took him in and soon introduced him to a young woman named Mabel Walters, who began teaching him English and eventually became his wife.

Three of Wieghorst’s goals were met in 1920 when he joined the U.S. Army and was assigned to the 5th Cavalry Regiment patrolling the Mexican border: He got back on a horse, became an American citizen, and saw the West. He spent three years with the cavalry before mustering out and taking a job as a cowhand on a large Arizona ranch. Every experience during this period — life on horseback, the vast landscape, weather, daily drudgery, or moments of drama — became fodder for his art.

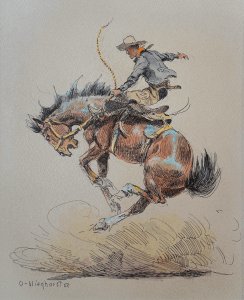

Bucking Horse and Cowboy | Watercolor and Ink | 10 x 8 inches | 1962 | Private Collection

As a self-taught artist, he carried sketching materials virtually everywhere he went. Much later in life, at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, where he was honored with a 1974 retrospective, he spoke of learning from direct experience. He told the audience when he painted a bucking horse, he knew what it felt like to be on a bucking horse. And to be bucked off. “Literally, I was taught from the ground up — when I was laying on the ground, I was lookin’ up at that horse. I know what it looked like!” he said, displaying his sense of humor and love of storytelling.

El Dorado | Oil on Canvas | 34 x 48 inches | 1966 | Photo: Roy Wieghorst

In 1923, Wieghorst returned to New York and joined the New York City police force, where he was assigned to the Horse Mounted Division patrolling Central Park. He also headed up the division’s show team, entertaining and winning blue ribbons in trick-riding competitions. He married Mabel in 1924 and continued painting, drawing, and sketching in his spare time. In the late 1930s, his work began appearing on calendars and magazine covers and was sold in the lobby of Madison Square Garden and a gallery in the Biltmore Hotel.

By the time Wieghorst retired from the police force in 1944, his art was gaining increasing attention and ever-higher prices. The following year, the family moved to El Cajon, California, where he set up a studio and focused full-time on his art for the next 43 years. In the process, Wieghorst became friends with actors and politicians, regaling them with stories from his life. “He was likable and outgoing. He captured a room as soon as he entered it,” remembers Raymond Johnson, who represented the artist for 25 years as owner of Overland Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona. “It always seemed to me he was 10 feet tall; he had such a presence.”

Heading for Cowcamp, Montana | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 30 inches | 1971 | Collection of Cowboy Hall of Fame

In California, Wieghorst met for lunch every Tuesday for more than 20 years with three other men. They called themselves the “Do Nothing Club,” and among them was Neil Reagan, brother of the president. Through this connection, the artist and his wife, along with Johnson and his wife, Sue, were invited to the White House. Johnson remembers panicking when he realized, shortly before the limousine was to pick them up from the hotel, that Wieghorst always carried a gun, a habit from his years as a cavalryman, cowboy, and policeman. Johnson called the artist’s son in California. “But Ronald knows me,” Olaf protested. Roy convinced his father to leave the gun in the hotel’s vault — a good thing, Johnson says, since the security guards wouldn’t even let them carry in a wrapped gift for the president without X-raying it first. A headline in the next day’s newspaper read: “Two Old Cowboys Meet in the White House.”

Johnson describes Wieghorst’s artistic development as getting “better and better until he was a star.” He spent endless hours on trail rides or traveling the West in a pickup with a camper shell, absorbing the landscape, sketching, and learning as much as he could about Native Americans. At a time when many Navajo lived in remote and isolated areas of the reservation, Johnson says, “He was one of the few white men invited into a Navajo hogan.”

Airline Bag | Ink on Paper | 9.5 x 5 inches | Year Unknown | Collection of the Wieghorst Museum

Jim Daniels of the Wieghorst Museum notes that one trait the artist took from the Native Americans he met was to always give something in return, usually a piece of artwork, when he received a gift. The habit matched his natural generosity. In a coffee shop, he would doodle on a paper placemat, sign it, and give it to the proprietor along with a sizable tip. On a plane trip, he once drew a horse’s head and a Native American bust on an (unused) white paper bag provided for upset stomachs, signed it, and gave it to the flight attendant. The Wieghorst Museum now owns that bag, which has been framed.

Following Wieghorst’s death in 1988, Daniels led the effort to save the artist’s modest ranch-style home from being razed for development. The house was moved to downtown El Cajon and became the foundation of the museum, which contains not only a large collection of Wieghorst’s art but also Western historical memorabilia from his life. One item that will likely go to the museum eventually is a not-yet-completed Wieghorst catalogue raisonné by collector Jim Drye, who has spent decades researching and gathering information and images for comprehensive documentation of the artist’s work. He also maintains a website of Wieghorst prints.

Because Wieghorst produced up to 1,600 oil paintings, perhaps 5,000 watercolors, and as many drawings, the project is an enormous undertaking and too large to publish in print. But Drye, who considers it a labor of love, would like to eventually make it available for public viewing in PDF format through the museum.

Cutting Horse | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 28 inches | 1943 | Collection of Jim Drye

As a young man in the early 1970s, Drye served in an Army mounted cavalry platoon at Fort Carson, Colorado, where in the bunkhouse, he came upon a copy of Western Horseman magazine with a story on Wieghorst and one of his paintings on the cover. Later he saw a print of the same painting, His Wealth, on a restaurant wall and began his quest to learn about Wieghorst and collect his art, especially prints. He was too shy to seek out the artist in person, but later Wieghorst’s son Roy asked him to take over his father’s artwork database. Drye also published the book, A Collector’s Guide to the Prints of Olaf Wieghorst. “His paintings are wonderful. They always seem to tell a story,” Drye says.

Today at the Wieghorst Museum, where, in keeping with the artist’s spirit of generosity, admission is free, docents help preserve not only the legacy of his art but also his character, which Daniels describes as marked by integrity, honesty, and a strong work ethic. Guiding schoolchildren through the museum, they talk about treating others fairly, with respect and courtesy. Says Daniels, “We tell the kids: If you want to be successful like Olaf, act like Olaf did.”

No Comments