08 Mar The Complexity of Life

“Before I start painting,” says Esteban Cabeza de Baca, “it’s usually a very euphoric moment of ideation.”

The artist’s dynamic, brightly colored, visionary works transmit this quality of euphoria. They express the deep, inseverable connections between all forms of life; between past, present, and future; and between ancestral, current, and future inhabitants of Earth. In doing so, they inspire feelings of possibility and joy. “I focus on making things I haven’t seen before in art,” Cabeza de Baca says, “while also finding inspiration in addressing environmental issues, with hope as the driving force.”

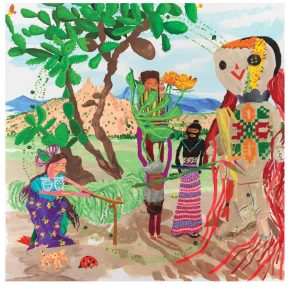

Medanales Golondrinas | Acrylic on Canvas | 72 x 72 inches | 2023 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Currently working from a studio in Long Island City, New York, the Indigenous Chicano painter has sensitive roots that reach all the way to his birthplace in San Ysidro, California. “We had a house on the corner of Averil Street,” he says, recalling a dwelling so close to the border it was “basically Mexico.”

Even more than this uniquely liminal place between two worlds, the people around him — including one particularly strong elder — most profoundly shaped Cabeza de Baca’s sensibility as a person and artist. “My great-grandma Bondita was an intense woman who lived through the Mexican Revolution,” he says. Until she died at 97 years old, Bondita was “a resilient personality who only spoke Spanish,” he recalls.

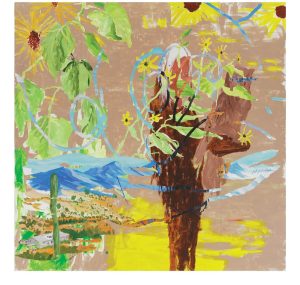

Ultima | Acrylic on Canvas | 60 x 60 inches | 2021 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

“She went to church every day, never drank or smoked, and made us offer whatever we had to others. She was very generous, and opened up the house to neighbors and family, especially those who’d just come to the U.S.”

Growing up in Bondita’s presence was “conceptually inspiring to my practice,” Cabeza de Baca says. “We had a garden in the back of the house where she raised chickens, pigs, and goats, and also grew what we ate. She would sing to her plants and take such good care of them by simply paying attention to how they responded to love. I think that really influenced me — seeing how my great-grandmother would find medicine in nature and care for it in a beautiful symmetry.”

Bondita’s vital and capacious heart is palpable in the artist’s paintings. In many of his works, a multitude of lives coexist: tangles of sunflowers, cacti, grapes, blue corn, and birds of paradise flowers; ladybugs, butterflies, and bees; various avian species, four-legged animals, and humans. And there are beings who defy categorization, such as ethereal-yet-earthly Indigenous ancestors and the traditional Mexican cloth dolls and Kachina dolls who inhabit some of Cabeza de Baca’s recent works. He received such dolls from his mother, who also led him to connect with painting nearly three decades ago.

“It was the one thing my mom could use to calm me down,” he says. “I didn’t start talking until I was 5, so my parents used art to get me to express myself. And I think I really delved into it so much that I’m mostly a visual thinker now.”

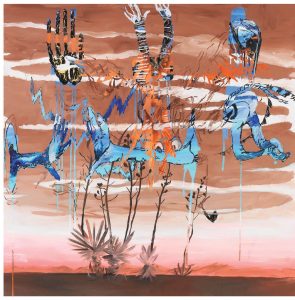

Besar La Tierra (Green Vein in Her Throat, Green Wing in My Mouth, Green Thorn in My Eye) | Acrylic on Canvas | 60 x 180 inches | 2020 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Indeed, Cabeza de Baca grew up to become a highly-educated artist — he holds a BFA from Cooper Union, an MFA from Columbia University, and studied at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam — adept at both sharing and provoking thoughts through his work. His paintings invite wildly fresh ways of thinking about the world we inhabit. Deeply imagined and futuristic works such as Besar la Tierra, Ultima, and Golondrinas accomplish this in part by defamiliarizing landscapes — and evolving the genre of landscape art itself.

“He plays with perspective in a physics-bending, interdimensional way,” says Garth Greenan, founding director of Garth Greenan Gallery in New York City, which held a solo exhibition for Cabeza de Baca in the summer of 2023. “There are conceptual components to his work that add layers and depth, but the paintings themselves are visually gripping in ways that reward sustained attention.”

Looper | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 60 inches | 2020 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Abstract rings, circles, and swirls of color overlay Cabeza de Baca’s landscapes, offering a chance to see deeply into or through the landscape itself — to see nonlinearly into the ever-present past, into the cosmos, or into a future state of harmonious relationship with the natural world. “I’m interested in how abstract painting of the New York School can speak to the history of landscape painting of the Southwest,” he explains. “We as artists have to hold many stories in our head while also ignoring them in order to make compelling work. So, for me, these works are about questioning how we tell history while also questioning the national boundaries we carve into our own mental maps of space in this country. I want people to expand their vision, but also see how their existence depends and originates from nature.”

“I’m interested in how abstract painting of the New York School can speak to the history of landscape painting of the Southwest. We as artists have to hold many stories in our head while also ignoring them in order to make compelling work.” —Artist Esteban Cabeza de Baca

“Esteban attempts to give a voice to nature by making it a protagonist in his work,” says Gabriel de Guzman, director of arts and chief curator at Wave Hill, a public garden and cultural center in New York City where Cabeza de Baca has shown his paintings and sculpture. “He depicts the landscape with utmost sensitivity and from a point of view so different from the colonist/settler mindset of land as property that can be conquered, owned, developed, and mined for natural resources.”

Host | Bronze | 84 x 84 x 60 inches | 2022 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

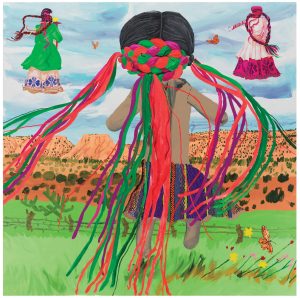

This view is also evident in the paintings and sculptures Cabeza de Baca has made with his longtime partner, accomplished artist Heidi Howard, who will join him in creating work for a summer 2025 exhibition at the Harwood Museum in Taos, New Mexico. Their collaborative works express their shared awareness of an all-encompassing interdependence. “Collaboration is in everything we do as human beings. We rely on ecosystems to provide nourishment and labor to gather resources, and we are responsible to take care of nature as much as we can,” says Cabeza de Baca. One painting the pair co-created, Braiding Sweetgrass (titled after the book by Robin Wall Kimmerer), “contrasts origin myths of settlers with those of Indigenous people,” Cabeza de Baca explains. “One origin myth connects with sin; the other with multi-species collaboration.” The pair also brought that latter, holistic worldview to Host, a bronze sculpture of two human figures who are verdant with the living, native plants to which they are literally hosts. “Our work is about pointing to the fact that we need collaboration to survive the approaching environmental catastrophe. Humans need each other, even if we do not always agree.”

This spirit of collaboration also exists on a smaller, more intimate scale between Cabeza de Baca and his own paintings. Sometimes, he says, “you have to allow the process to breathe rather than forcing your will onto a painting. Painter and painting isn’t a one-way relationship, but rather, the work speaks back to you. So, I think as much as you have to be an artist, you also have to be a sensitive viewer who knows when to stop yourself from overpainting.”

Golondrinas | Acrylic on Canvas | 72 x 72 inches | 2023 | Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

At other times, his approach is more active. “I can see my work in my mind’s eye almost as if it’s an environment or a memory of a climate. Then comes translating that vision, which can be successful or miserable. … Some paintings require a visual density to reflect the complexity of life, so they require a lot of time spent looking and creating,” says Cabeza de Baca.

His reverence for the complexity of life is part of what makes Cabeza de Baca such a standout presence among young 21st-century artists, as someone who is working to change the way we perceive our intricately woven world. “There is a rich history of ecological art,” he says, “and in some ways, it distracts us from seeing reality. I’m interested in expressing feeling nature with paint.”

The phrase “feeling nature” captures some of the magic and possibility within Cabeza de Baca’s work: It dissolves the illusion of separateness, and speaks not only of how we feel the natural world, but also how the natural world feels us.

Cabeza de Baca’s first solo exhibition in California opens May 8 at Parker Gallery in Los Angeles. The show explores his father’s time as a bodyguard for Cesar Chavez, 1960s psychedelic Chicano culture, and themes of organizing, agrarian culture, and cross-cultural solidarity.

No Comments