17 Mar In the Studio: A California Outlook

For half a century, Tom Killion’s Japanese-inspired woodblock and linocut prints have celebrated the wild places of California, from the High Sierra’s rugged peaks and ancient forests to the Pacific coastline’s peaceful beaches and rocky coves. So, in a genuine sense, Killion’s first and foremost studio has always been the great outdoors, where he spends weeks each year backpacking, camping, and sketching the scenes before him in pen-and-ink or pencil. “I carve all my blocks straight from my sketches,” he says. “And I always look through my sketchbooks for the images I want to work on next.”

Tom Killion sits outside of his studio and home in Inverness Park, California, sketching Black Mountain, a beloved landmark just across the wetlands of Tomales Bay. “A black Bic ballpoint is my favorite sketching tool,” he says. “The ink survives my sketchbook better than pencil.”

A fan of Killion could imagine, then, that his studio — where he carves blocks, makes limited-edition prints, and attends to the other business involved in an artist’s working life — might also focus on nature. And it briefly did during his earliest creative years growing up in Marin County, north of the Golden Gate Bridge. “When I was a teenager in my parents’ house in Mill Valley, on the side of Mount Tamalpais,” he says, “I had in my bedroom a nice little desk with full windows on two sides, looking out at a big pine tree. I made my first little linoleum-cut prints at that desk as Christmas cards. And then I made pictures of Mount Tam, using one little gouge and an X-Acto knife, 4-by-4-inch blocks from the local art store, Speedball water-based ink, a piece of glass, and a little rubber roller.”

Two redwood trees stand on either side of the driveway that leads to the studio and the Killion family’s brown-shingled home beyond.

That sublimely simple setup gave way to less-than-idyllic yet ever-more-professional art-making arrangements over the next two decades. The reason for their lack of perfection wasn’t at all that Killion’s devotion to art waned, but rather that his range of academic pursuits grew dramatically. After graduating from Tamalpais High School, he majored in history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and followed his bachelor’s degree with 14 months spent hitchhiking through Europe and Africa. He returned to earn a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in African history from Stanford, making lengthy research trips abroad. He later co-authored the Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. That’s not to mention stints teaching African history at Bowdoin College, the University of Asmara in Eritrea, and San Francisco State University.

Busy and multifaceted as he’s always been, Killion continued making art, expanding upon his skills, knowledge, and capabilities. He worked for years in a succession of studios in Santa Cruz, a laid-back beach town beautifully situated at the northern end of Monterey Bay. As an undergrad, he learned through an extracurricular program how to print handmade books. His first — 28 Views of Mount Tamalpais — was inspired by 36 Views of Mount Fuji from the early-19th-century Japanese master Hokusai. Killion sold his edition of 92 copies for $100 each, which not only financed his post-college trip to Europe and Africa, but also, upon his return late in 1977, paid for a high-quality German-made Asbern printing press, the same one he uses to this day.

- Traditional Japanese steel gouges and chisels are arrayed for easy access when carving woodblocks.

- Within easy reach, a rack holds Killion’s “furniture,” uniformly measured small pieces of wood he uses to lock his printing blocks precisely into place on the bed of the press.

- Sewn onto Killion’s printing apron is a pad of insulation foam that prevents him from “wearing my hip out when I lean against the press.”

- The artist purchased his hand-cranked Asbern cylinder proof press back in 1977.

- The Asbern’s printing cylinder and the carriage for its ink rollers help make his high-quality, precision work possible.

- A small traditional Japanese printing brush is used to whisk away wood chips while carving blocks.

Killion set up the press in a converted “very tight two-car garage,” one block from the beach. “That’s where I did my first big project,” he says, referring to The Coast of California, a volume of woodblock and linocut images he originally printed by hand. He released it as a limited edition of 126 copies in 1979 through his own small publishing company, The Quail Press — all while commuting to Stanford for his graduate studies. The book went on to be commercially published in 1988, and both editions are now widely sought after by collectors.

Killion returned from his trips to Europe and Africa in late 1982 and took over a friend’s studio space in the alleyway carriage house of an old Victorian in downtown Santa Cruz. He continued working there into the new century, watching the neighborhood decline with drug dealers and 1970s radicals still on the run from the FBI. “I called it ‘the rat hole,’” he says with a wry laugh.

- On the opposite end of the room from his printing and carving areas, a large table is dedicated to framing his artworks.

- Assorted Japanese water stones and leather-honing blocks are the ideal tools to keep the cutting edges of his carving and gouging tools precision sharp.

Meanwhile, he’d married Carolina Frota in 1993, and, with the proceeds from The Coast of California, he pitched in with some friends to buy an almost 12-acre piece of wooded slopeside land in Inverness Park. About an hour up the coast from the Golden Gate, it was an idyllic area backed by the protected expanse of Point Reyes National Seashore and overlooking the southwestern tip of Tomales Bay.

For Killion’s 3 acres, Santa Cruz architect George Koenig — an old bike-riding friend of his — designed a brown-shingled house “like those I’d always wanted growing up in Mill Valley.” It became the home where his two children — son Kai, 28, and daughter Camila, 19 — grew up.

Hand saws are ideal for cutting up the wood blocks Killion carves for printing. On the wall above them, he displays a painting his daughter Camila made for him a decade ago, when they were reading author Arthur Ransome’s children’s book, Swallows and Amazons.

In the same style, just steps away from the house, rose the 22-by-19-foot studio of Killion’s dreams. In one corner sits his press, surrounded by the same efficient arrangement of worktables, woodblock and linoleum carving tools, and printmaking materials to which he’d grown accustomed in the “rat hole.” Separate areas are devoted to framing and shipping, and there’s also a small office space. All around are shelves for neatly stacked carved blocks, ready for Killion’s print-to-order work, whose editions of 180 have not yet reached their limit; a lifetime of journals and sketchbooks; and reference books on subjects ranging from art and nature to African history and California poetry (Killion has collaborated on three titles with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and environmental activist Gary Snyder).

- On his ink-mixing plate, Killion carefully combines a selection of colors, including dark sky-blue, yellow, and green — along with extenders that thin the ink and enhance its transparency — to achieve just the right shade of “pale jade bluish-green.”

- He stores his assortment of printing inks — and cleaning rags, of course — on an open shelf underneath the mixing plate.

- Using the ink he has just mixed, he prints the green color in a work based on a sketchbook drawing he made at Lost Canyon on a backpacking trip in the High Sierra.

- Once that layer has dried completely, Killion prints his “key block,” which is typically the darkest (usually black) and most highly detailed stage of the several blocks he uses to make one of his multicolored prints.

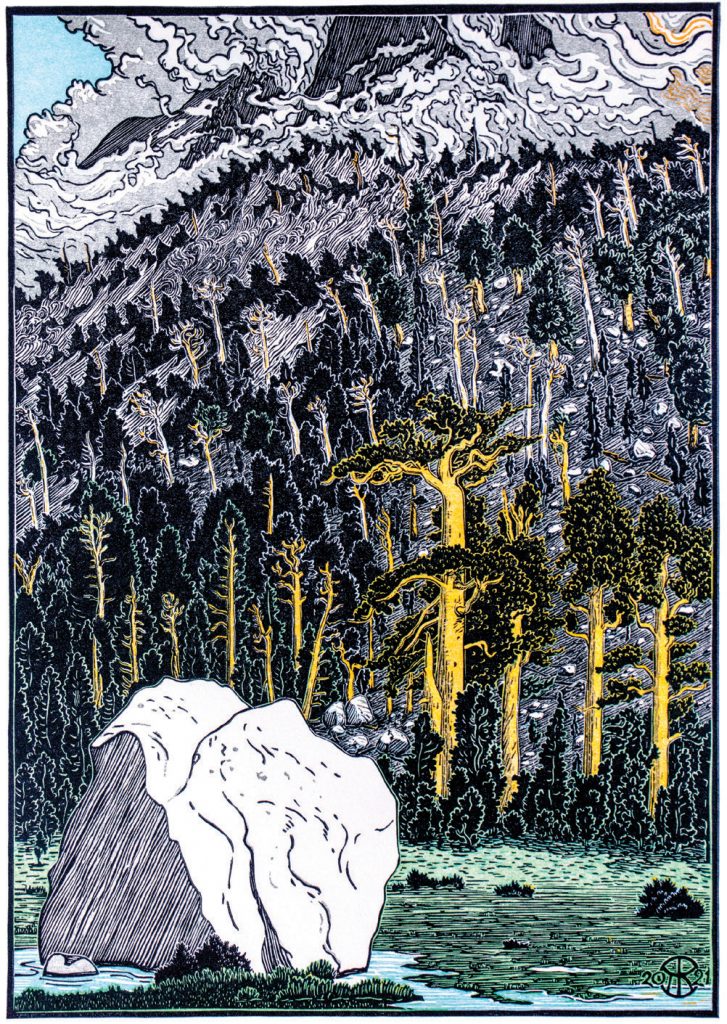

- Ancient Forest, Lost Canyon | 5-Color Multiblock Woodcut Print | 9 x 12 inches | Edition of 185 | 2021

Hanging in frames on walls and tacked or taped to the bulletin board above his desk and to door and window frames is a lifetime of memorabilia, including some of his earliest drawings and prints, posters announcing past shows of his work, artwork by his daughter and artist friends, and full-color postcards Killion sends out announcing the availability of his newest editions. Of that bulletin board, he says with some chagrin, “All those Post-Its and other stuff go all the way back to 2002. Then along came the fully digital world, and in 2015, I stopped putting anything up there. It’s a little history of the end of the paper world.”

- Carved in 1970, at the age of 16, a linocut of a quail was “my earliest successful art print,” the artist says. He slightly enlarged the image to 9.5 by 12.5 inches for three giclée limited editions between 2013 and 2019.

- Postcards Killion would send out announcing new works inspired his friend, Gene Holtan, to create his own versions and mail them to Killion.

- Stacks of blocks for single-color works await printing.

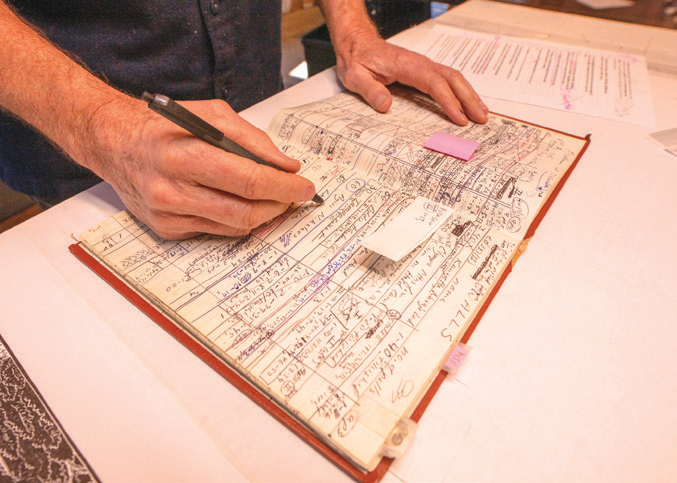

- The artist tracks all editions in a logbook.

Killion sharpens a V-gouge on a water stone.

One essential element of the studio harks back to that first place in Mill Valley where, as a teenager, Killion began creating art. The studio’s windows facing east to the wetlands of Tomales Bay, across the water to Black Mountain (a peak he loved seeing in childhood family outings), and north to the bay laurels and redwood trees surrounding his property. Looking out at the setting, Killion sums it all up with words that could serve as his mantra: “It all starts in nature.”

No Comments