17 Mar Perspective: Louisa McElwain [1953–2013]

It was the day of Louisa McElwain’s annual studio tour. Organized each summer by Evoke Contemporary, the event would see invited collectors and friends gather for a barbecue, painting demonstration, and tour of the artist’s studio and small ranch just north of Santa Fe. The gallery’s director, Kathrine Erickson, arrived early that day to help prepare.

As the time for folks to arrive grew closer, Erickson noticed that the field where cars were to park was thick with tall hay. She asked how the cars would park there. “Oh, I’m going to cut the field,” McElwain replied. She climbed on a tractor to mow the pasture, but it broke down in the driveway. An increasingly anxious Erickson asked what they would do, and McElwain produced a giant wrench and repaired the tractor. Then, 15 minutes before guests began to arrive, McElwain announced she was going inside to take a bath.

“That’s how it rolled with her,” Erickson says, laughing.

Artist Louisa McElwain often set up an easel on the back of her trunk to paint landscapes that captured her attention.Photo courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

Unflappable and independent, with energy to spare and an easy physicality rooted in the earth, McElwain lived as she painted: joyously, untroubled by convention, and happy to walk right up to the edge of what others might consider advisable or even possible. Until her untimely death in 2013 at age 59, she created large-scale paintings entirely on location, the earth’s energy moving up through her body as she stood in front of an enormous canvas attached to the back of her pickup truck. Wielding a masonry trowel duct-taped to a long stick, she applied paint thickly and rapidly in a kind of choreography she called “a dance to the tempo of the evolving day.” The more dynamic and unpredictable the conditions, the more she enjoyed the challenge — capturing the feeling of massive landforms, billowing clouds, and ever-changing light in her favorite Northern New Mexico painting spots.

McElwain’s widely collected art was met with admiration and awe. It earned numerous honors over the years, including best of show and other top awards at national exhibitions. When Erickson first encountered it in the mid-1990s, the paintings she saw were small, since that’s what the representing gallery could accommodate. Yet Erickson remembers being “stopped in my tracks, breathless at the powerful energy — the masterful use of color and the confident and bold yet quite minimal strokes.”

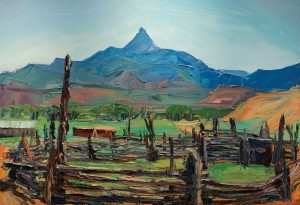

Be Thou Strong My Habitation | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 72 inches | 2012 Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

Five years later, the two began working together, and in 2009, the painter joined Erickson’s Santa Fe gallery. Now representing McElwain’s estate, Evoke retains a large number of paintings, as well as boxes of her journals which are being cataloged and monotypes that will be released at some point. A show of her paintings is set to open May 28 and run for two months at Evoke. “Louisa is still a really strong presence in my day, every day,” Erickson says.

Back when McElwain would pop in the door on a weekly basis, her presence somehow always attracted people into the art space, Erickson says. “I could be sitting in the quiet gallery all day by myself, and Louisa would walk through the door, and a crowd would appear. For a long time, I thought she was playing a joke on me,” she says. But McElwain herself was surprised and amused by the phenomenon. “Some people just have this magnetism,” Erickson adds. “She was a party wherever she went.”

El Dramadero | Oil on Canvas | 44 x 62 inches | 2007 Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

Mark Sublette, who represented McElwain for 20 years as owner of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona, was also struck by the painter’s irrepressible enthusiasm. He recalls some years ago preparing to close the gallery for the day. Suddenly McElwain arrived unannounced, “brimming with excitement, her rough hands covered in sky blue paint.” She lived 550 miles from Tucson but was so happy with a new body of work that she couldn’t wait to show it to him. “Every painting’s composition, color sense, and subject choice represented her feelings at the moment of creation,” Sublette says. “Her emotional energy, expressed through her thick, delicious palette-knife strokes, was like no other artist I’d ever seen.”

McElwain may have made it look easy and fun to translate the excitement of wind, vast open spaces, and landforms into paintings, which then read viscerally as the earth and sky she experienced. But early on, she spent years seeking foundational art instruction that would give her a trained jumping-off place for developing this approach. Raised in rural New Hampshire, she was steeped in an appreciation of nature, taking long walks in the woods with her father and spending summers at the lakeside cabin her great-grandfather built. She later described herself as possessing a Romantic’s soul. But her first attempt at formal art education, at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, set her in the midst of a cerebral, abstract art mindset that was the antithesis of what she sought.

Navajo | Oil on Canvas | 54 x 62 inches | 2005 Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

Leaving college, she traveled to Florence, Italy, and spent a year studying drawing with the 82-year-old classically trained artist, Nera Simi. On her return, she made another disappointing dip into art school, this one enthralled with Minimalism, before landing at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. There she finally found artists and mentors, including Alex Katz, who taught landscape painting as a legitimate subject of contemporary art. Then, at the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts, she became immersed in the study of color under the instruction of painter Neil Welliver, a student of pioneering color theorist Josef Albers. “I came to understand how light is created through the relationship of color,” she later recalled.

Pasture, Spring | Oil on Canvas | 46 x 64 inches | 2001 Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

By the time McElwain moved to Northern New Mexico in 1985, she was ready for the clear light, high-desert hues, expansive vistas, and ever-changing weather of the place she soon came to love. “Here in the West,” she once said, “it seems that the canvas is never big enough.” Enormous works completed on location required what she called “extreme painting”: big, energetic gestures to reach all corners of the canvas and keep up with rapidly shifting conditions. It was an intense physicality reminiscent of such mid-20th-century New York School “action painters” as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

For McElwain, the process involved the “largest possible tool for the job,” as she put it. Eliminating the brush was an intentional curb on detail, allowing her to move paint with “velocity, articulate delicacy, and sensuous impasto,” she said.

Photo: Lindy Powers

Yet while her mark-making echoed the Modernists’ focus on the painting surface and revealed abstract qualities, especially up close, her interest was not in abstraction itself. Rather, the passion in her art reflects both an admiration for the long tradition of representational landscape painting and her own in-the-moment connection with the land. That connection often led her to leave small bits of dirt, stone, grass, insects, or broken glass in the painting if they blew into it while she worked. As she explained, “Rather than a vignette that gives an idea of a piece of a landscape that’s disembodied from my actual relationship to it, what I’m painting is my relationship to it.”

As McElwain matured artistically, her style became even looser, stronger, more confident, and involved a greater amount of paint, Erickson says. “It was much more expressionistic, wild, and free.” Over the years, as well, she cultivated an ever more profound relationship with certain vistas, among them the oxbow curve of the Chama River and the iconic red cliffs of Georgia O’Keeffe fame near Abiquiú, New Mexico.

Parking her truck and attaching an easel to the back to take in the view of these spots, time and again, never felt like repetition to her. Instead, she said, her deepened connection to beloved places was part of what allowed her to “take greater leaps into larger canvases, surrendering to the inquiry, and to paint with ever more trust and joy.”

Extra Terrestrial | Oil on Canvas | 44 x 62 inches | 2009 Courtesy of EVOKE Contemporary

Indeed, as Sublette explains, “Art and Louisa McElwain are synonymous. The focus and joy she generated with each canvas will be her lasting legacy.”

No Comments