19 Oct In the Shadow of Magnitude

Select paintings by Western art giant Frederic Remington may fetch millions of dollars at auction, but the illustrator-cum-artist would not have seen his works realize such sums during his life or in the immediate aftermath of his death in 1909.

Remington’s reputation was well established in his life-time through illustrations in widely read magazines, but the posthumous popularity that attends his works today saw its rise in the 1950s when New York dealers sought paintings as well as bronzes for a broadening market for Remington’s renderings of the American West, says Jack Morris, founding partner of the Scottsdale Art Auction.

Remington reigns as a Western artist whose flow has not been hampered by any substantial ebb, and a dwindling supply matched with steady — even urgent — demand has in recent years seen certain works sell far above their expected prices at auction.

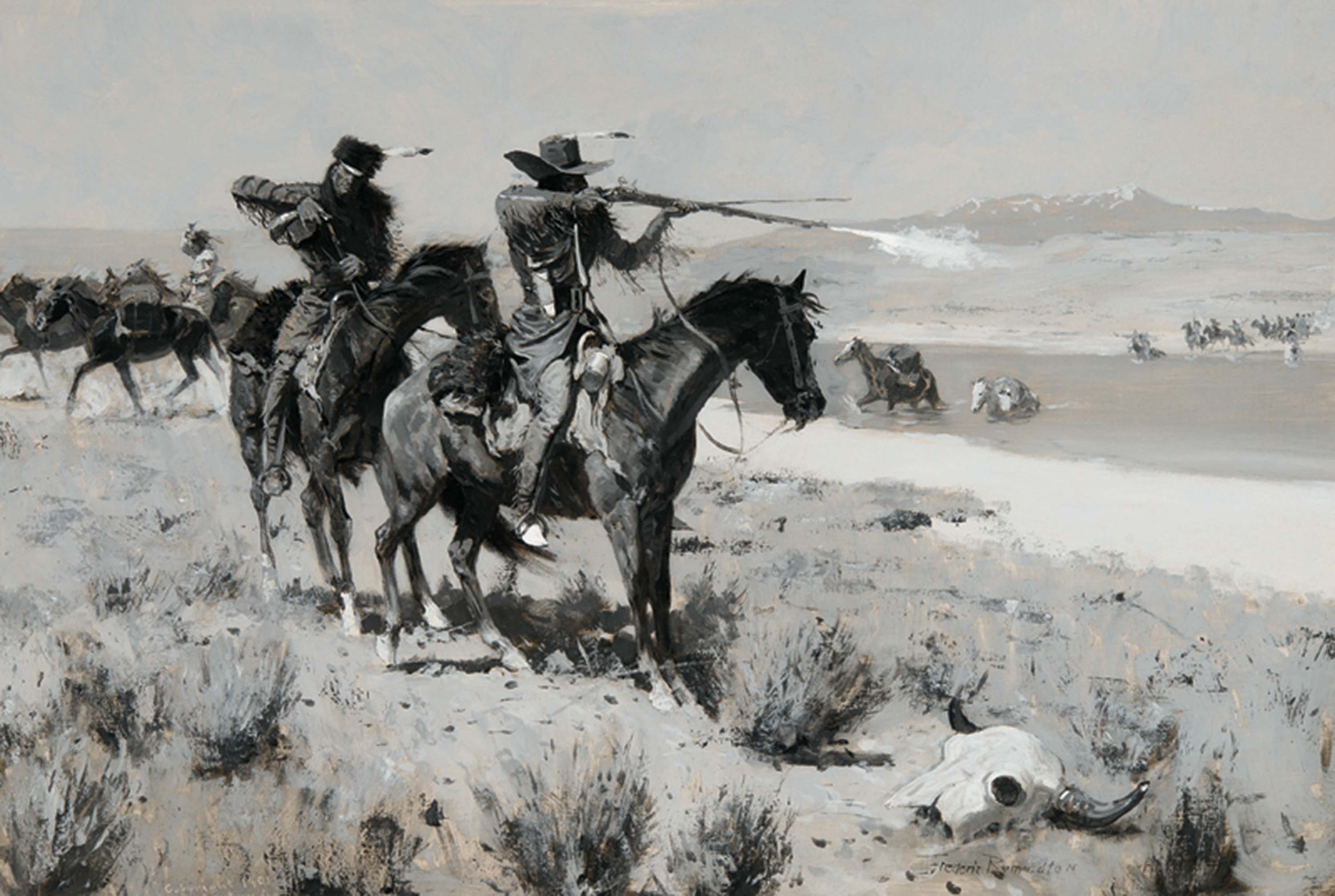

A black-and-white oil by Remington, Pack-Horse Men Repelling an Attack by Indians, sold last year at the premier Western art auction in Arizona for $1,035,000, despite an estimated range of $500,000 to $700,000.

While many artists, even those of prodigious talent, will not achieve the posthumous heights of Remington, those whose works continue to command handsome figures after their deaths may share certain attributes. A key measure is the success an artist enjoyed during his lifetime, says Morris.

“The basis is how well known the artist was to the public prior to death, the degree of popularity attached to the deceased artist’s paintings or sculpture, and if the theme — in Remington’s case, the American West — has enduring appeal,” he says.

Today, Western art is a taste that has arrived rather than one pining for a destination. Yet for all the ranks of buyers, sellers and admirers, the Western art world can be said to be uniquely personal. And so it was with regret and a lasting sense of loss that the close-knit community of thousands received the news that two of its stars, Dave McGary and Gib Singleton, had fallen.

Those closest to the late sculptors say the faithful and discerning followers they attracted in their lifetimes are as steadfast now as before.

Collectors of McGary’s signature Native American narratives in bronze uniformly open a discussion about the works by referring to the importance of their relationship with the celebrated artist.

The team of artisans hand-picked years before by McGary for casting and finishing his intricately detailed tabletop and monumental sculptures are to continue producing a certain number to meet the needs of longtime collectors as well as those who have McGary was a preeminent Western sculptor, acclaimed for his lifelike figures, and for his respect and understanding of the traditions and rich history of the Indian tribes he initially encountered in the American Southwest, says Bill Ridenour, whose law firm in Phoenix specializes in representing artists and galleries.

McGary was a teenager just off a ranch in Cody, Wyoming, when he gained a grant to study casting techniques in Italy. The tutelage by bronze masters was paired with McGary’s flair for sculptures whose hues and detail all but defy their medium.

Ridenour says McGary’s pieces — in the permanent collections of such museums as the Smithsonian Institution and on monumental display before such venues as the Houston Astrodome — have seen a markup at auction, which may be tied to drive-by collectors who wish to possess a work they were eyeing before the artist’s death last October at age 55.

“People get off the fence after death, especially if a piece being considered for purchase is limited,” he says.

In addition to the reputation of the artist and the following he has attracted, factors that raise prices include masterworks. In his last months, McGary devoted himself to depicting historic tribes of the eastern woodlands in a series entitled Trophy Hunters.

Yet Ridenour is among several collectors who say owning a McGary is more of a calling than a calculated investment, that love of the art trumps love of money.

Thomas James, executive chairman of Raymond James Financial, says his admiration for McGary as an artist was matched by his appreciation for the sculptor as a human being.

He describes McGary as the recorder in art of Native American history and culture.

“In Dave’s case, what is meaningful in the development of his sculpture was his commitment to telling the stories of the Indian families he had met and of the deeds and practices of their ancestors,” says James. “And his portrayals were authentic — in the weaponry, the shield designs, the ceremonial robes.”

McGary lives on through his work and through a reputation he left in the hands of his wife, Molly, to hold and to cherish.

“His work was very much a part of our lives and our existence,” she says. “It was extremely important to him, and to me, that his legacy lives on.”

As does the creative genius of the late Gib Singleton, whose bronzes depict figures from Christ to bronco busters and have been favored by everyone from popes to rodeo riders. Singleton’s work has been exhibited everywhere from the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan to the Vatican Museum in Rome.

Singleton, whose contributions to Western civilization include restoration of Michelangelo’s Pietà, is the creator of what has been termed “emotional Realism,” and he himself captured both the spirit and the substance of the style with these words about his sculptures: “I’m not decorating somebody’s living room. I’m not decorating somebody’s garden. I’m decorating somebody’s heart.”

The unlikely tale of how the son of a Missouri sharecropper rose to become an artist of world renown is etched in bronze from the cross on the crosier of the late Pope John Paul II to Tatanka, the figure of a Native American astride a white buffalo at the Gib Singleton Museum of Fine Art in Santa Fe.

Paul Zueger cultivated and cared for Singleton in the decades since he first represented the classically trained artist’s work at Galerie Zuger in Santa Fe. In the months after Singleton’s death in February at age 78, Zueger has seen a resale at $150,000 of the sculptor’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, depicting the riders described in the Book of Revelation. The same piece had fetched roughly $32,000 just 10 years before. For Zueger, an expert whose instincts have been refined by 40 years in the art world, the mix that makes for rising values of artworks was realized in Singleton.

“You look at how much education the artist has, whether he knows what he’s doing and whether the work speaks to you. Gib surpasses the mark in all of those categories,” says Zueger.

Zueger was at Singleton’s bedside in 2004 when doctors gave the sufferer of emphysema just a week to live. He rose from what had been presumed to be his deathbed to complete the monumental figures for the Stations of the Cross later installed in a prayer garden at the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe.

“As Gib completed each station, his health improved and he lived another 10 years to complete some of the most phenomenal works of his career,” Zueger says.

John Goekler, director of Singleton’s namesake museum, recalled Singleton at work with his eyes closed, attentive to the world within and oblivious to the world without.

“Gib said at one time that what a sculpture looked like was not as crucial as what it felt like. He didn’t just create art: he channeled it,” Goekler says.

- Dave McGary “Trophy Hunters” | Bronze | 34 x 26 x 198 inches (masterwork)

- Gib Singleton, “Four Horseman of the Apocalypse” | Bronze | 28 x 35 x 32 inches

- Gib Singleton, “Tatanka” | Bronze | 19 x 16 x 7 inches

No Comments