01 Feb In the Studio: A Working Space

From his quiet, secluded studio in rural Northern California, Peter Holbrook paints brilliantly colored landscapes of the Southwest. Outside the large windows that flood his working space with light are the green and dun browns of the inland forest. But on the walls of this hand-crafted studio, where he has worked for more than 30 years, the Grand Canyon is alive and beckoning from three large canvases that occupy one wall.

It’s not that Holbrook hasn’t painted California landscapes, but he shied away from the iconic redwoods of this region to focus on the rocky coast of the Pacific Ocean and the High Sierras. Still, the artist wanted more.

“What I missed in that work was color,” he says. “This part of California is not extremely colorful. I’ve heard it described as a big salad bowl. Look out the window and you see 80 shades of green with no reds, no purples. I wanted more color.”

Holbrook found what he was looking after visiting his parents in Arizona and then rafting the Colorado River in 1982 with other artists, including Merrill and Jeanne Mahaffey.

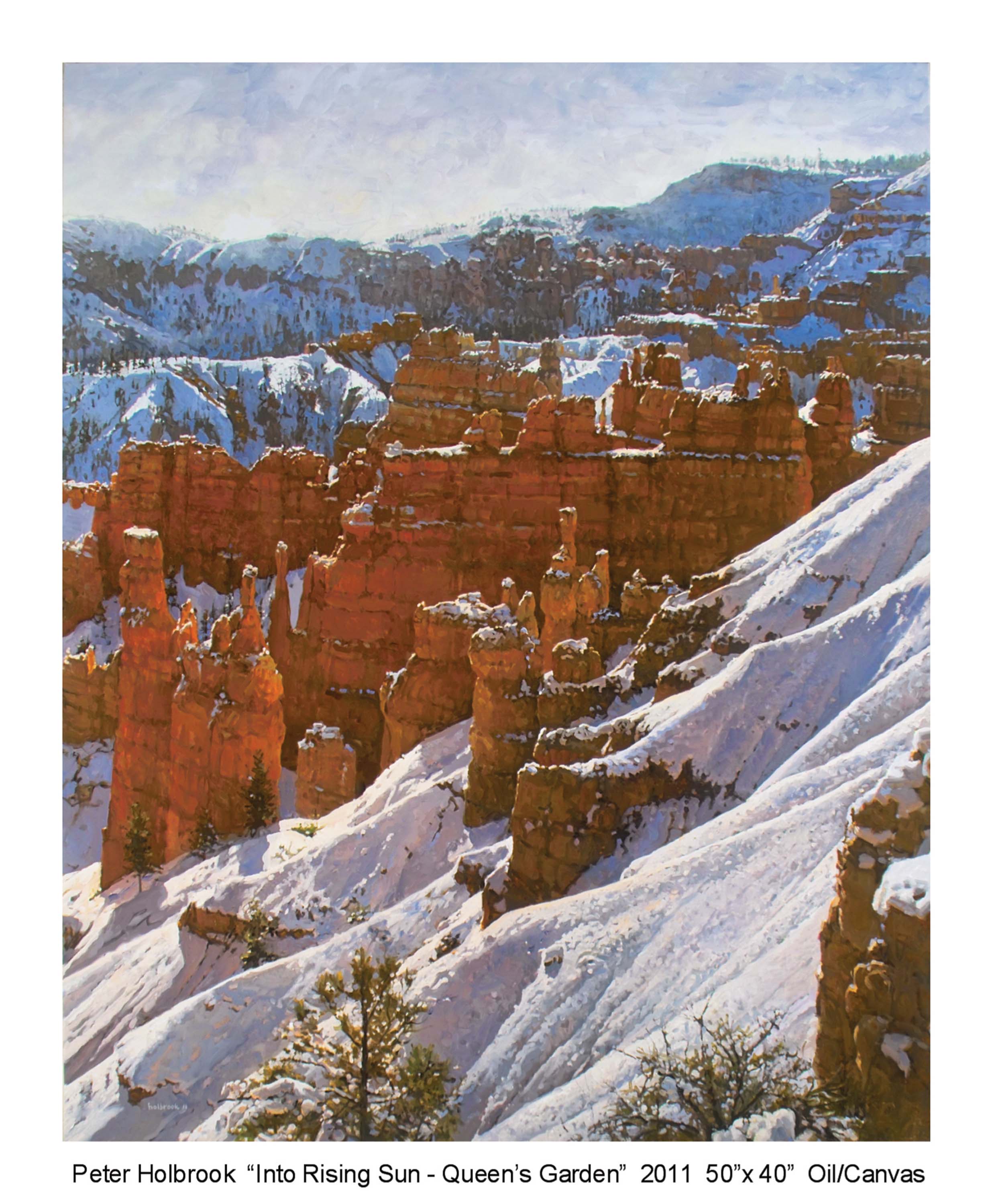

“It was all there in the canyons of the Southwest; the anatomical forms I love to work with. The rock formations are very anatomical. And colors! The entire spectrum of colors, colors that you just don’t see except perhaps in a sunset, and I don’t want to paint sunsets. But all those yellows, pinks, oranges and purples are in the landscape of the Southwest.”

Holbrook began painting when he was 16, majored in art at college and did his post-graduate work at the Brooklyn Museum School of Art. From there he moved on to Chicago where he painted the inner city and honed his skills working in many styles. For several years in the 1960s, Holbrook painted in Grisaille to understand the range of light and dark. As his subjects became more complicated and full of detail, the artist moved into photography. The first subjects were highly mechanical and architectural.

Holbrook trained himself to employ photo reference material, a method which has become standard practice for painters working in large format. For some 30 years now, he has been photographing the great canyons of the Southwest and returning to his studio to paint what he has photographed. Although the studio is only a few steps from his house, it provides the private world he needs to work without distraction.

“Painting is a right-brain activity. When I’m down here, I turn the telephone off, nobody comes to visit and I’m in that right brain and the meditative state that I’m very used to.”

It was with that singular frame of mind that Holbrook created the studio in which he works four to five hours each day. From the time of his arrival in California in 1970, he had built numerous working spaces as time and funds permitted. From a plywood tent which got him through the first winter to the house/studio he built for himself and his partner, Holbrook’s working space has always been a priority. When the couple was expecting their first child in 1980, Holbrook realized that the half of the house devoted to his darkroom and studio would be needed for their growing family. “By then I knew what I needed: high ceilings in the painting area and 32 feet of room to stand back for large canvases. I needed tall doors for moving my work, which ranged up to 7 feet tall. I needed lots of skylights and an area for framing, building stretchers, crates and some furniture,” he says.

Over time, and with the same meticulous detail he is known for in his paintings, Holbrook custom built precisely the space he needed. Built into the ground to make the most of natural insulation, the studio has a number of features allowing the artist to control both ventilation and light. Skylights have closing covers that slide in tracks. His easel glides up and down on a compound pulley system. An adjustable mirror allows Holbrook to study his works in progress from a reversed view, “a trick I learned from DaVinci,” he explains. Various systems allow the artist to work from a seated position and to have access to visual reference material while he paints. Everything that moves is on wheels. “I had no architectural style or model in mind,” the artist explains. “Only the limitations of my budget. The building was designed for making paintings. It’s the office I work in 300 days a year.”

The work he produces continues to make waves. Gallery owner Beth Lauterbach says that Holbrook is considered one of the preeminent painters of the canyons of the Southwest, especially the Grand Canyon. She is the owner of Scottsdale Fine Art and has represented him for four years. She credits Holbrook with special skill at capturing atmospheric and lighting changes throughout the seasons of the year.

“Anyone familiar with the Southwestern landscape can tell by looking what time of day or year is represented in his paintings by the length of the shadows. People also appreciate the different vantage points he paints, his bird’s-eye views or views from the base of a cliff, and the layer upon layer of sediment. There is a lot of variety in these aspects of his work and people find they can’t step away but want to move closer.”

Lauterbach’s gallery is long and she likes to hang one of his larger paintings on the back wall because it draws people in. She says they come in thinking they’re looking at a photograph but she urges them to move closer until they can see that what looked like photographic detail is actually small brushstrokes and that what they are seeing is a painting.

“The most important thing about him as a painter,” she says, “is his ability to capture the canyons and the atmosphere and that he is detailed and quite prolific. It’s ingrained in him. He has to keep painting.”

Now in his seventh decade, Peter Holbrook can look back on a career that includes 55 one-person shows and 54 museum group exhibitions across the country. His work is included in 16 museum collections including the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Art Institute of Chicago. His attention to detail and continued effort to understand the art of painting have brought him both satisfaction and success.

“I’m just trying to make really interesting paintings,” he says. “Paintings that will hold their interest over time. My clients tell me that they got to looking at one little area of a painting after perhaps owning it for years and would see a detail that they had missed, or hadn’t really noticed in the brushstrokes or paint handling, or the number of colors in a seemingly flat area.”

“I won’t change anything about my work until I think I can make an improvement and I don’t really see an improved direction from where I am now. I feel satisfied and I want to do more of the same. What happens naturally is that you just get better and it goes on for a lifetime.”

No Comments