16 May In the Studio: Alive with Light, Color and Imagination

Many know Dale Chihuly, the educator, artist entrepreneur, and revolutionary in the American glass movement. His works are included in more than 200 museum collections worldwide, and his medium is unmistakable. Transformed by red-hot heat, glass becomes elastic, shaped by forced air, gravity and artistic vision into colorful architectural installations and light-consuming vessels. Chihuly changed the way the American public thought about glass, using monumental scale and complex layering to transform “craft” into fine art.

“People for centuries have been fascinated with glass,” he says. “It’s the most magical of materials.”

What you might not know about Chihuly is that he’s also a passionate collector, and art is only a small part of it. At one point, he owned 28 Aston Martins.

In his Pacific Northwest studio called the Boathouse, entire rooms are dedicated to his collections, which include American Indian art, antique children’s books, painted ceramic string dispensers, bathing suits, mid-century radios, wooden tennis racquets, old kitchen appliances, European carnival masks and Edward Curtis photographs. Some items are stored in warehouses; others, such as the Pendleton blankets and the Native American baskets that inspired his Cylinders and Baskets series, are displayed in rooms throughout his studio. In nearly every hallway or corridor, there is a collection.

Chihuly, who was born in Tacoma, Washington, in 1941, is drawn to water environments. He used to surf. Venice, Italy, where he studied at the Venini glass factory after receiving a Fulbright Scholarship in 1968, may be his favorite city; and he is famed for comparing his medium of choice to the ocean, “Glass itself is so much like water. If you let it go on its own, it almost ends up looking like something that came from the sea.”

It seemed natural, then, that in 1990 when an old boat factory located on the shores of Lake Union in Seattle, Washington, came on the market, he did not let the opportunity pass. Acquiring the property, he reimagining the warehouse as a living and working studio.

To realize this vision was not easy, but Chihuly was no stranger to the challenges of construction. He holds a bachelor’s degree in interior design from the University of Washington, and he worked briefly at an architecture firm before earning a master’s degree in sculpture at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. He also remodeled the basement of his mother’s home in the style of Frank Lloyd Wright, his hero, before college.

Although Chihuly no longer lives in the Boathouse, the 11,354-square-foot studio is a handsome retreat. The lakeside structure serves as the artist’s studio and reception hall for philanthropic events. It’s where Chihuly and his team of artisans create the majority of works used in his installations throughout the world. And it’s as unique as the artist who conceived of it.

The control center is the Hot Shop. A great, pine-paneled room that takes its name from four furnaces that line one of the long walls and can blaze at more than 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit. Teams of accomplished gaffers, or glass blowers, expertly wield long metal blowpipes through the fire, returning molten pieces to the “marver,” a steel table where the viscous glass is rolled. The men and women who work with Chihuly are accomplished artists and many have worked with him for years. Some were his students at the Pilchuck Glass School in nearby Stanwood, Washington, which Chihuly co-founded in 1971.

By the time Chihuly arrives in the Hot Shop, music is blaring and everyone is engrossed in a project. He is a big man with a craggy face framed by hair that refuses to be tamed. He’s wearing a Hawaiian shirt, blue slacks and the famous patch over his left eye, an accommodation after an injury in an auto accident in 1976. Molten glass has stained his sneakers, flecks of dripping color and patterns that suggest a Jackson Pollock painting.

Chihuly’s studio functions much like the workshops of Renaissance painters with a master and several assistants. There’s great camaraderie and respect among the glassmakers and Chihuly, who makes colorful, poster-size drawings of his ideas and signs them on the bottom with his familiar signature scrawl. He no longer blows glass himself, but this also provides a valuable perspective that is unknown to the glassblower in the thick of creation.

In the Hot Shop, he cruises among the men and women, casually surveying their work. He’s relaxed, affable and appreciative, generous with praise. “Fine,” he says. “Good work.” Occasionally, he offers a suggestion or asks a question. He picks up a wood paddle and carefully taps a work in progress, coaxing the molten glass into a more refined shape or encouraging the gaffer to make it bigger. He firmly subscribes to the theory that bigger is better.

Chihuly pushes limits, especially to make objects larger. It’s a dangerous task, and when successful, the results are spectacular. But there’s always the risk of failure by pushing too hard. And even after producing an amazingly large piece, success is not assured. Glass, for all its fragility, is heavy. A large object may be dropped and shatter on the way to the annealing oven to cool. When that happens, it’s as if the air has been sucked out of the studio. But only for a moment. Then it’s back to work.

He has no patience with the debate about whether what emerges from the Hot Shop is art or craft. “Call it art, call it craft. I don’t care,” says Chihuly, laughing. “I get my kicks out of people seeing my work.”

Chihuly is renowned for ambitious architectural installations in cities, gardens and museums, and the magic of his art is dazzling on site. In the Boathouse pool room, where Chihuly exercises, the swimming pool floor is carpeted with glass forms, protected by clear glass. Fantastic flora bloom in exotic colors, capturing and casting light in unusual ways through the water. Large, twisted sculptures — which Chihuly calls chandeliers — sparkle in a rainbow array above the pool and are endlessly reflected in mirrored walls that multiply their magic.

Just as exotic but more intimate is the room-sized aquarium Chihuly designed for his young son. The walls are made of glass tanks filled with tropical fish and the artist’s Seaforms. The room is semi-dark, dramatic in phosphorescent light that gives the impression of being beneath the ocean. The boy could watch the fish for hours, comfortably reclining on an upholstered bench against the wall.

In the Northwest Room, meanwhile, Chihuly’s collection of Native American crafts are presented along with his glass interpretations. Inspirational baskets and examples from his Cylinder series are displayed on unpainted shelves. His extensive collection of Native American trade blankets are stacked or draped over tiered wood poles that extend from wall to wall, displaying the vivid patterns and colors. A rare 1914 Indian motorcycle stands in front of the blankets.

The dining room, called the Evelyn Room after a vintage sign, occupies the entire rear width of the Boathouse. A row of windows overlooks the lake. And a massive table carved from a single Douglas fir tree stretches more than 80 feet across the room. A row of colorful Chihuly chandeliers dangles above. Spotlights enhance their colors and free-form shapes.

Seattle is the art-glass capital of the United States, with more glass artists than any city in the country. So it seems appropriate that Chihuly, the virtuoso who started the entire movement, calls it home. Here, he will continue to create works of art that play with light, embody kaleidoscopic color and enrich our lives.

Editor’s Note: This summer, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, will open dual exhibitions by Dale Chihuly. Chihuly: In the Gallery and In the Forest will be on view in the museum’s temporary exhibition gallery and North Forest from June 3 through August 14, 2017. Once the gallery portion closes, Chihuly: In the Forest will remain on view from August 16 through November 13, 2017.

- The lap pool is a symphony of subtle hues and exciting organic shapes that suggest nature but are creations of Chihuly’s imagination. The room includes objects from several of the artist’s series, including chandeliers suspended from the ceiling and “Seaforms” and “Persian” forms under the shimmering water. Photo: Jan Cook

- Working along a blow pipe in the Hot Shop, Chihuly oversees the work of his accomplished gaffers. Photos: Scott Mitchell Leen

- Chihuly loves color and imports glass rods in hundreds of hues from Germany. They are arranged by color in cubbies along one long wall in the Hot Shop. Nearby walls display sample shapes and glass pieces in various configurations used to create sculptures.

- Dale Chihuly drawing on the Boathouse deck. Photo: Russell Johnson

- Original sculptures are highlighted in the Boathouse Library. Photo: David Emery

- The Northwest Room showcases Chihuly’s collection of Native American baskets and Pendleton blankets along with examples of glass art they inspired. Photo: Scott Mitchell Leen

- The Evelyn Room, named for a vintage trade sign, overlooks Lake Union. It is furnished with a dining table that’s more than 80 feet long, a single slab of wood from a fallen Douglas fir. Above the length of the table, a row of chandeliers sparkle. Photo: Scott Mitchell Leen

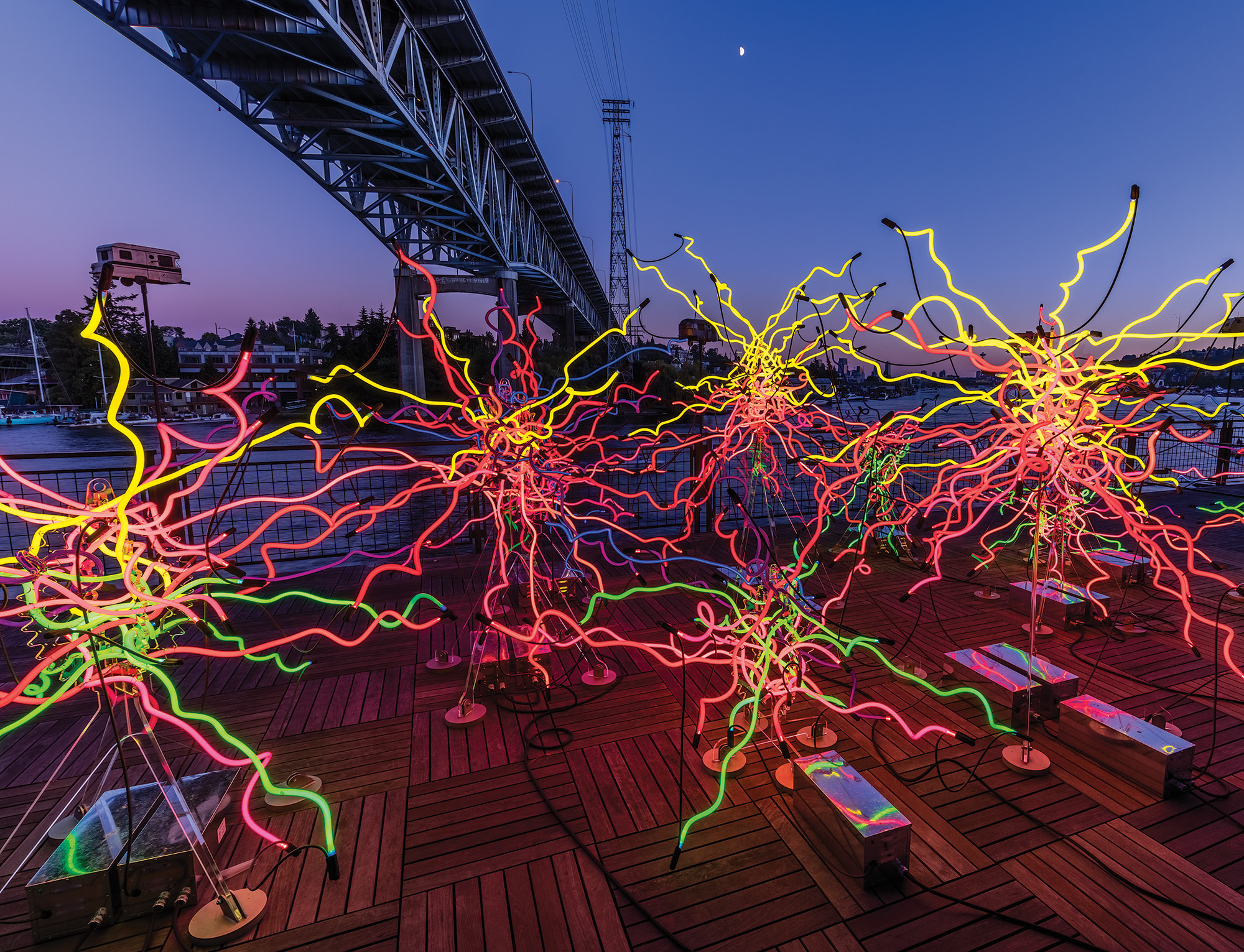

- As early as 1967, Chihuly was using neon, argon and blown-glass forms to create roomsized installations. Photo: Nathaniel Willson

- The Boathouse sits serenely alongside gentle bay traffic. Photo: Russel Johnson

No Comments