04 Aug In the Studio: Freedom on the Wing

The muted roar of a departing jet temporarily overpowers Greg Woodard’s boom box. Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” is playing, his favorite song. He turns up the volume and continues to work the clay. Woodard is wedged into his diminutive studio at the Ogden-Hinckley Airport in Utah, putting final touches on Freedom, a life-size rendition of Ghost Rider, his signature, limited-edition bronze. “I like to listen to music while I work, old stuff mostly. I kind of get a rhythm going,” says the soft-spoken sculptor.

At barely 500 square feet, this is the only studio the artist has ever had. Woodard’s creative niche flanks a walkway in the Gateway Center at the south end of the airport. One wall is windows. He has an open-door policy, mostly because there’s no door. “Sometimes I feel like I’m in a fishbowl,” he admits. “But people walking by, mostly off-duty pilots, stop in to look and talk and I like that.”

Woodard likes being around things that fly. As a boy growing up in Arizona and Utah, his sketchbook was always in hand when his father took him on bird-watching outings. “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t draw or paint. I’ve always wanted to observe and recreate things. I don’t know what it was, it’s just inside of me.” Birds of prey were his favorites. They’ve been the subjects of many of his most popular bronzes.

Woodard is self-taught. In high school, he resisted his teachers’ urgings to study art and sculpture. “I was more interested in girls, ski racing, birds and fast cars,” he grins. Besides, he had his own teacher and mentor in his father, a high-school shop teacher and carver, who taught him how to use the specialized tools of the trade.

Woodard was a quick study. In his early 20s, the artist honed his raptor and waterfowl wood carvings to a fine point. Never afraid of risk, he quit his job as a brakeman with Union Pacific Railroad at age 25 to pursue his passion. “I just decided I was going to be an artist, so I quit,” he recounts. Soon, his incredibly realistic birds were bringing top dollar at national shows. He was twice named world champion at the Ward World Championship Wildfowl Carving Competition in Ocean City, Maryland.

Woodard transitioned to sculpting in his mid-30s. “I guess I got tired of being judged,” he says, noting that sculpting offered far more freedom of expression than ultra-realistic bird carving.

In sculpting, Woodard’s imagination was set free. Ever the nonconformist, he developed unique techniques. At the foundry, he painstakingly chips castings away, leaving just enough slurry to coax dramatic contrasts from the bronze. He applies subdued, flat patinas sparingly, often dripping them across the form for effect. Recently, he’s experimented in casting steel, using patinas and acids to impart color or rust to the metal. The results are breathtaking.

In sculpting, Woodard’s imagination was set free. Ever the nonconformist, he developed unique techniques.

Woodard was a master falconer for many years, and birds of prey remain among his favorite subjects. “When I started doing figurative stuff, I got so I almost felt like a bird. To me, they are the ultimate expression of wildness and freedom.”

Freedom — the spirit reverberates in all his bronzes. When Woodard eased into sculpting human forms, mostly Native Americans, in the 2000s, he sought to express that same spirit. “With Ghost Rider, for example, I wanted to capture the feeling a young Sioux warrior on horseback must have had in 1825, racing across the prairie. It’s joy and elation; you feel like you’re flying, your arms are out like wings. It’s sort of the same feeling a kid gets today when he gets his first car. It’s freedom.”

Woodard’s work draws high praise from fellow artists. R. Tom Gilleon, the renowned, Montana-based Western artist, will join Woodard in September for a two-man show at the prestigious Altamira Fine Art studio in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “Greg is definitely a storyteller, very unconventional,” says Gilleon. “So he’s not just doing a horse, he’s telling you what the horse is doing.

There’s nothing shallow or superficial about his bronzes. Everything nonessential has been eliminated and that, to me, makes his work strong.”

Woodard has been with Altamira since 2009. Dean Munn, the exhibitions director, says his bronzes are compelling and thought-provoking. “They’re impressionistically textured and tactile in nature, unique qualities in the Western art market. He’s a great fit within Altamira’s roster of artists by virtue of his individualism, devotion to calling, high-production quality and signature expressive style.” Freedom of expression is dear to Woodard’s heart. “I like to take chances now. I kind of think I’ve paid my dues. I’m on a great adventure and I can feel my momentum growing. I hope my work will last a long time and bear testimony to the journey.”

- Some of Woodard’s collectors don’t drive to his studio, they taxi up in corporate jets.

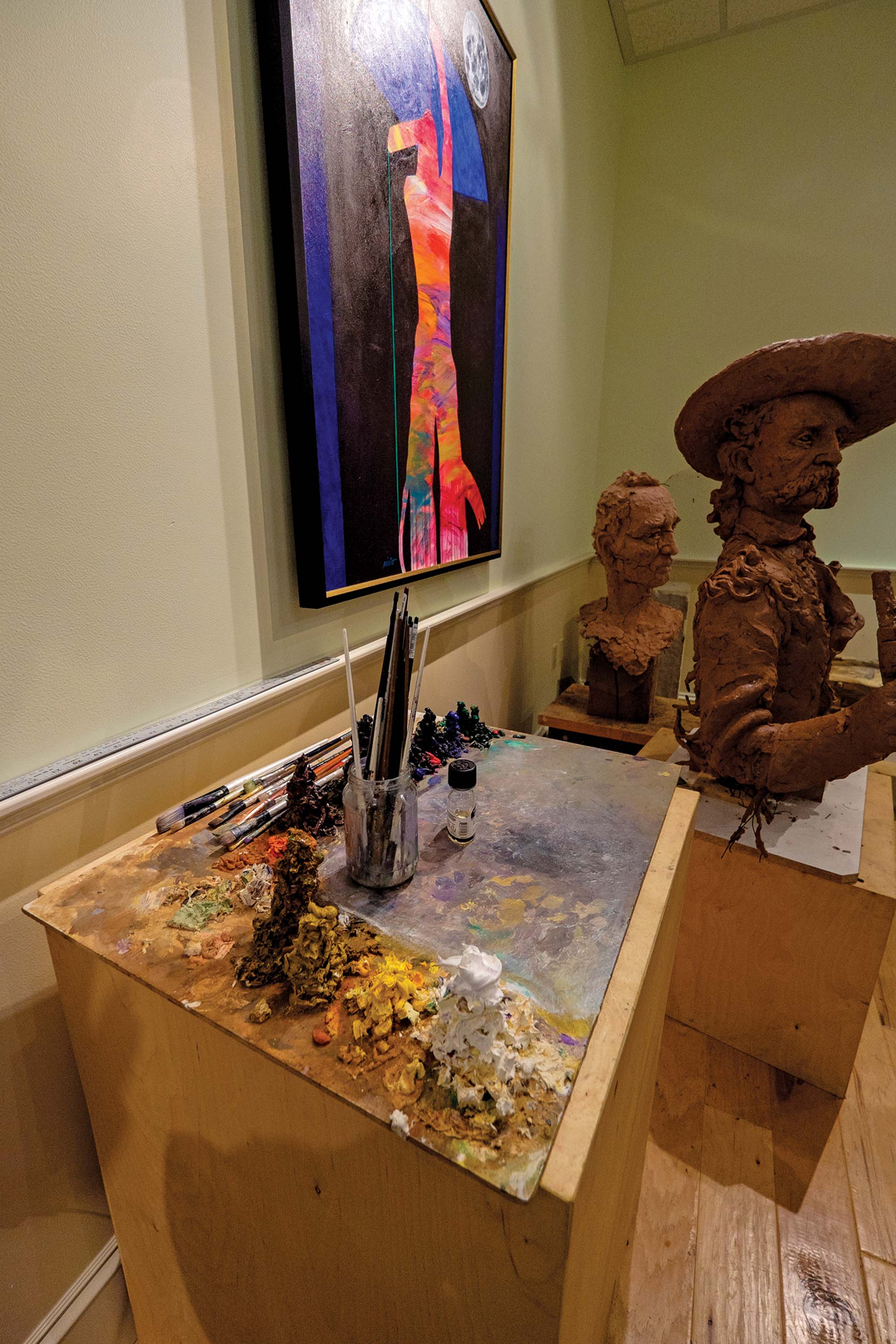

- A glimpse at Woodard’s studio reveals breadth and depth, from paint to weathered wood and bronze.

- Sculptor Greg Woodard stands in an ogden, Utah, airport hangar, flanked by Three Chiefs, still in clay and one of several works in progress.

- Woodard’s palette and brushes are used to mix and apply finishing touches to his “Snowy Owl”.

- Woodard’s monumental rendition of Ghost Rider, his signature piece, nears completion before casting.

- The sculptor’s tools include a simple block of wood, used to move and texture the clay.

- Woodard always admired General George armstrong Custer’s bravery and honors him with this exquisite piece, bound for the foundry.

No Comments