01 Dec In the Studio: George Dombek

Strolling up the flagstone walkway, I grin at the child’s tricycle perched atop a stone wall and gaze in wonder at the Hobbit-esque tool shed smothered in orange flowers. Hmm. I’m not sure what to make of that giant yellow cube sitting on the lawn. Dogwoods, sycamores and evergreen pines guard this 16-acre wood, the magical world of watercolor painter George Dombek. “I won’t tell you about the tricycle,” he teases. “You will have to figure that one out for yourself.” He says later, “The yellow box is just art.” (Since then, he has painted the box blue).

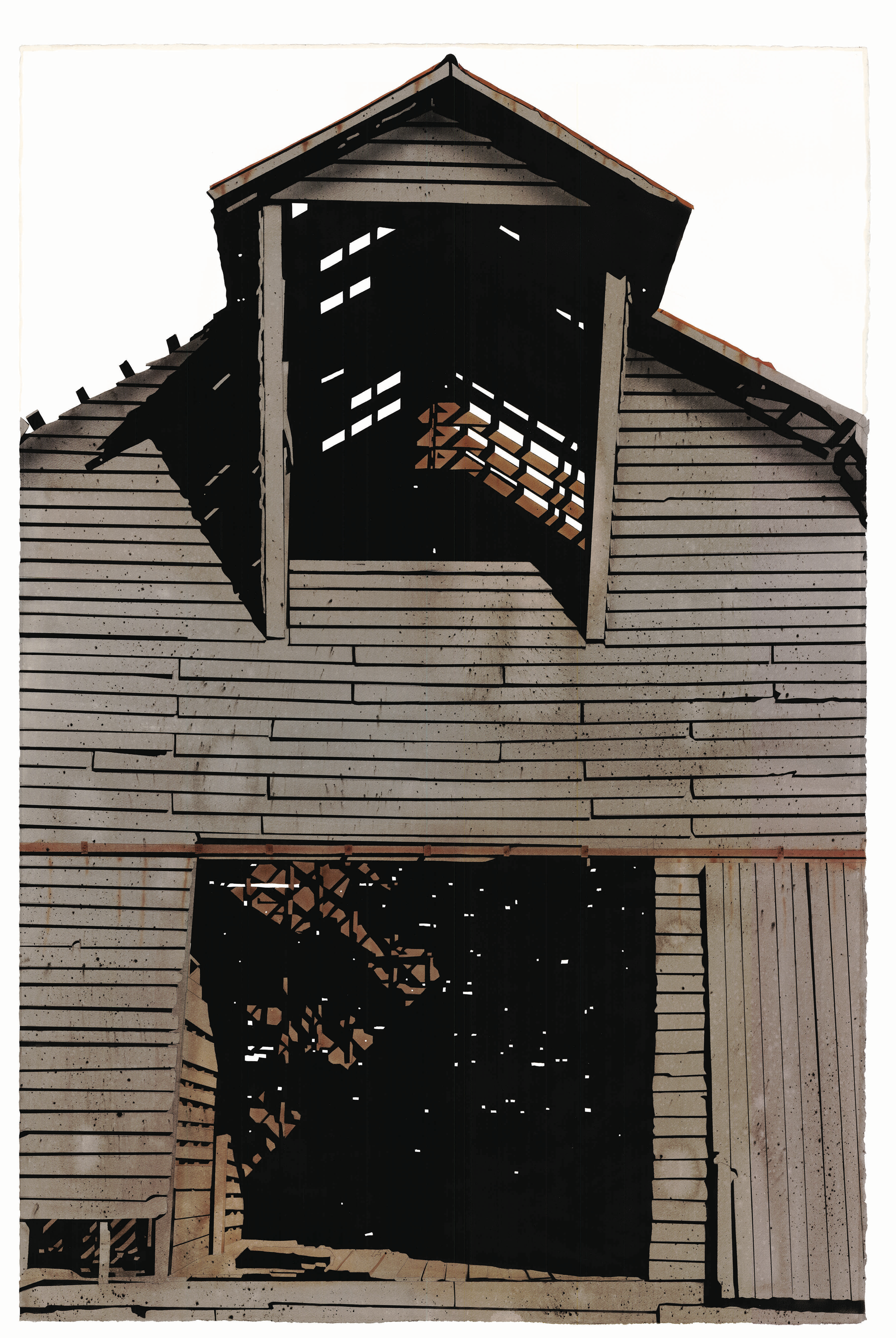

Here in northern Arkansas, literally in the land of Goshen, the 69-year-old artist has returned from Florida to his roots. His 6,000-square-foot studio and gallery is a fitting testament to his boon years as a professional still in his prime. These days he is preoccupied with barn paintings with a goal of capturing one barn from each of the 75 counties in Arkansas.

With a B.A. in architecture design and an M.F.A. from the University of Arkansas, Dombek has designed and built an inspiring studio gallery. When he purchased the land in 1984, the area was barren except for an old hay barn. Since the beginning, he has slowly planted more than 4,000 trees. In 1994, Dombek erected a home with a working studio. But he soon outgrew that space and launched plans to build a separate studio six years later. As his reputation grew and collectors descended, Dombek decided to expand and add a formal gallery in 2012 for art receptions with comfortable zones to meet with clients privately.

Serving as his own architect provided Dombek every advantage. According to Dombek, many architects want commissioned projects to serve as signature monoliths, but for him, the simple design exists to frame the art within. The exterior is made of corrugated metal which also matches the industrial siding of his home steps away. The warehouse material is low-maintenance, he says, and never needs a coat of paint. Doors are wide enough so his paintings can go in and out easily. He has created watercolors as large as 80-by-120 inches, so having the ability to transport work is essential. The 16-foot-high white walls are tall enough so he can hang works in progress. Windows are stationed above to allow for plenty of natural light.

Because he doesn’t want to be cramped, Dombek designed a second-story loft, a place where his assistants can scan photographs, research projects, order supplies and frame paintings. And because he did not want the public going up to the area, he hid the stairs behind a door.

His own work space is directly below, one filled with work surfaces with wheels for easy repositioning, clear acrylic cubbies for his brushes and paints and cement floors for easy rinsing. “I’m really attacking paper with big brushes and paint goes a lot of places,” he explains.

The prolific painter is well known for his iconic twig bicycle in a twiggy tree, dubbed Tour De Tree, in the sculpture garden at the prestigious Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in nearby Bentonville. As the story goes, Alice Walton, the Walmart heiress and founder of the museum, came over and saw his twig bicycle hanging from the ceiling. “She wanted to know if I could recreate that in bronze for Crystal Bridges, so I did.” Not only did he create a bronze, he sold four paintings to the museum at an undisclosed, but handsome price.

His two-story studio is a reflection of his career’s work, much of which is based on nature. Watercolors of stones, others featuring giant flowers, barren trees festooned with birds, more with butterflies on trees are displayed throughout. In earlier phases of his career, he painted San Francisco fire escapes, steel mills and abandoned tobacco barns. Unlike other traditional watercolorists whose works reveal a sheer pastel quality, his paintings are brilliant with vibrant tones and bold detail. Images are so exact in representation, you’d swear the paintings were photographs.

Over the course of his career, the man has accrued more than 80 awards and honors. He’s held more than 30 one-man shows and has had his work displayed worldwide from the Arab Heritage Gallery in Saudi Arabia to Chase Manhattan Bank in New York. He started life as an architect in San Francisco, but moonlighted as an artist. He later taught art to college students for nearly two decades in Arkansas, Florida, Saudi Arabia and Florence, Italy. It wasn’t until 1995 that he decided to paint full time, a choice he has never regretted.

A typical workday for George begins at 4 a.m. “I sometimes wake at 2, and I never sleep past 5,” he explains. From his house, he saunters into the studio and paints for three hours. After consuming breakfast and the daily paper, he pushes forward to work for three more hours. During his two-hour break, he may scarf down lunch and run an errand. For the final lap of the business day, he hits the studio again and produces until 5 or 6 p.m.

“I am working on a dozen paintings at one time right now. It is demanding and takes lots of focus,” he says. “For the things that are routine, I save that for end of the day. I jump from painting to painting. My creative process is in the morning when I’m not fatigued.”

In his gallery on the opposite side of the building, a bump-out cantilevered alcove with a floor-to-ceiling window faces nature’s gifts. This quadrant of trees and the flagstone path running between them is like a painting itself. It is an enviable haven where he can sit and let his imagination flow.

Also stunning is the antique 24-foot wooden ladder leaning into a skylight in the middle of his gallery. Surrounded by Dombek’s paintings, the room features hardwood floors and a couple of modern, steel-frame chairs. The rest of the room is bare except for the ladder.

Oh yes, there’s also that door. A steel door opens into a vaulted room where Dombek keeps 52 years of his life’s works under strict temperature control at 72 degrees Fahrenheit. Says Dombek, “I have produced thousands of paintings and will probably not sell all of them in my lifetime. What will happen if I do not protect them? I have grandsons, and I want to leave a legacy for them.”

The room is so sturdy that if there was a tornado, everything else would be blown away, and the vault would remain. In fact, he and his wife, Karen, and grandson hid there during three storm warnings a little over a year ago.

With 12-inch concrete-block walls with an 8-inch concrete slab on top and steel reinforcements, the vault is also flood proof and fireproof. “That room is not leaving here. I feel very confident that if the gallery and studio were to disappear, this would not. In an emergency, everything would collapse around it.”

The 18- by 24-foot-long safe room also supports more storage space on the second level with a pull-down ladder. This is good, because Dombek shows no signs of decreasing his output.

In progress is the remodel of his 1880s hay barn that sits on his acreage. Serving as a project for the architecture students at the University of Arkansas, the students will be designing an 8-acre sculpture garden around the structure with hopes of completing it by spring of 2014. As for the barn, Dombek will be the one restoring and retaining its historical integrity. “The floor is so unstable and in terrible shape.” Yet all of this is not daunting for the grandfather and artist who is patiently driving around town, collecting wood planks from discarded barns to replace his battered floor.

Just as his paintings are works of art, the grounds have become part of Dombek’s palette. He is particular about placement of every Adirondack chair, sculpture, chair swing and even the smallest birdhouse. “The last hour of daylight I like to walk around my property and look at how I can improve and work the landscape. I don’t separate living from art. To me, all of it is one and the same.”

- A weathered trike greets visitors by the front walkway.

- Artist George Dombek has painted in watercolor his entire career.

- From the loft and catwalk, assistants can talk to Dombek about current projects as he works below.

- The safe room keeps his works at an ideal 72 degrees.

- The gallery space is punctuated by an antique 24-foot ladder Dombek rescued from the barn.

- George Dombek, “Arkansas Barn Two” | Watercolor | 60 x 40 inches | 2013

- The fire pit in the back of the studio serves as a cozy sanctuary at the end of a busy day.

- In the work space, Dombek poured cement floors for easy cleanup and maintenance.

- The bay window is the perfect place for contemplation as Dombek begins his day.

No Comments