29 Dec In the Studio: Lisa Neimeth and Mary Daniel Hobson

Lisa Neimeth and Mary Daniel Hobson are two northern California artists — one city-based, the other settled at the beach. They have never met, yet their creative journeys have put them on similar paths through New York, New Mexico and San Francisco. Both have created workspaces in their home environment. Both share a quiet confidence, a sparkling tranquility. Although each artist creates in a different medium, the work itself carries similar surrealist undertones, with found objects and ephemera common tools in their artistic alchemy.

The Sunset is a densely populated neighborhood of San Francisco. Rows of semi-detached homes run lockstep up the cement hills. Through the criss-cross of telephone wires, the silhouette of the deYoung museum rises out of the verdant rectangle of nearby Golden Gate Park. The orange span of the Golden Gate Bridge is visible in the distance.

In the middle of one block lives an urban oasis: a double lot surrounded by a jasmine-covered wood fence. Outside the fence there are honking horns, idling buses. Inside, we find a 19th-century farmhouse, singing birds, a bubbling fountain. The contrast is immediate and jarring, in a good way. It is here that native New Yorker Lisa Neimeth finds her inspiration. Her studio, once the farm’s chicken coop, is encased in glass and filled to the brim with a visual cacophony of collected objects, curios, iconic miniatures, clay and kiln-ready pieces.

This workspace, quite literally a glass house, conveys an openness — an almost seamless integration into the natural world surrounding it. As is often the case, achieving simplicity takes an enormous effort. Throughout its 100-plus-year history, the space had morphed from a chicken coop to a potting shed to a rather ramshackle catch-all. Neimeth and husband, Peter Dickstein, immediately set to work cleaning, sheetrocking, tiling and adding plumbing and electricity. Her goal was to create “an intimate space where I could be close to the materials I was using. I wanted to … bring the outside in. It makes me forget that I am in the city.”

Neimeth has been working in ceramics since college. Initially a hobby that continued through master’s degrees in social work and urban planning, Neimeth’s sculpture career began in earnest after the 1997 birth of her son. Influenced by the work of Joseph Cornell, travels in Central and South America and her interest in iconography, Neimeth began a series of assemblage sculpture that is at once provocative, witty and highly accessible.

In recent years, time spent studying at The Ghost Ranch in Santa Fe has honed Neimeth’s vision and direction. Seized by the desire to “make something that people could actually put their hands on and use,” Neimeth turned her attention to tableware. Modifying the tenets of her sculptural technique, Neimeth began incorporating “impressed found object imagery and beautiful glaze finishes.” She sees her work as a natural extension of the Slow Food movement and the current focus on organic and locally grown produce — a “slow dish movement” — if you will. “It is nice for people to eat from something so special yet so functional. People take so much care in what they eat — it only makes sense that that care extends to how they eat.”

The response has been immediate. After her first “open studio,” Neimeth’s work was commissioned by the Museum of Craft and Folk Art (MoCFA) in San Francisco, and picked up by local retailer The Gardener. Says Susan Strolis of MoCFA, “I was drawn by the simple imagery, the sweetness of the image — and thrilled with the opportunity to showcase a local artist.”

And what does Neimeth make of the attention? “It’s just so rewarding to do all this in my own backyard — in my little chicken coop.”

Driving the winding road into Muir Beach is equal parts scenic and harrowing — and not just a little like time travel. The town center, only 30 minutes from San Francisco, is identified by a colorful row of mailboxes on one side and an old English Inn on the other. Horse trailers dot the landscape; cypress trees bend as though supporting the thick fog. Just off this main drag and down an unpaved road, photographer/artist Mary Daniel Hobson and her contractor husband, Jon Rauh, have transformed a ’70s beach party pad into a serene, solar-paneled artist’s retreat.

Situated in the center of their acre of flat land — an almost unheard of bounty in these parts — is Hobson’s studio. Painted barn red to match her home, the workspace still maintains its original structure: a simple wooden building that belies the streamlined workspace within.

During the 2002 renovation, Hobson and Rauh replaced huge sections of the floor ruined by dry rot; installed a new bathroom; exterior doors; carpet; a faux wood-burning stove and flagstone hearth; and built a portico at the front entrance. The attic space was reconfigured to house a meditation area. Hobson carefully selected furniture that would enable her to most efficiently utilize the space: a large center work table, a flat file on wheels, bookshelves, an ergonomic computer desk, bulletin boards, Elpha shelving and a couch for reflection and repose.

Hobson’s studio is as much a part of her artistic process as it is a place to work. Says Hobson, “The studio is like the compost pile for my creative process, meaning that it houses all the nutrients I need to create my work — including tools as well as the wide variety of objects I have collected over time for using in collage, sculpture or still life. It is really my creative think tank … it is a retreat for me, a mental refuge of sorts. I love being in this space.”

Born in San Francisco, Hobson began taking photographs as a teenager. She studied art history at Vassar, where she became fascinated by the work of Lee Miller as a woman who was “influential on both sides of the camera.” Hobson returned west for post-grad work, earning a master’s degree in photography from the University of New Mexico. For her master’s thesis, she traveled to Paris to immerse herself in the work of Picasso muse and surrealist photographer Dora Maar. It was during this time that Hobson’s work significantly changed. “I was no longer satisfied with plain black and white photography; I wanted to express the life of emotions … to somehow describe what was living beneath the surface.”

Classes in 19th-century film processes led her to discover Kodalith, a very high contrast film that renders subjects in a pure black and pure white film positive, leaving them virtually transparent. Hobson combined her Kodalith images of the human form with found objects such as insects’ wings, handwritten letters and/or pieces of music to create mixed media collages of emotionally layered complexity. Thus Hobson’s deeply evocative series, Mapping the Body, was born. Modernbook Gallery founder Mark Pinsukanjana observes, “What first drew us to [Hobson’s] work was the layering and multimedia aspect of her pieces … [they] leave an impression of nostalgia and longing.”

Hobson’s current series, Sanctuary and Evocations, have brought her for the first time into the world of digital photography, the latter incorporating her deft use of assemblage into a flat print, shot on the deck of her Muir Beach studio during the morning fog.

Leissa Jackmauh is a native Clevelander, which has given her a gimlet-eyed appreciation for just about everywhere else. She lives with her husband and children in Marin County, California.

- Neimeth’s workspace, quite literally a glass house, conveys an openness – an almost seamless integration into the natural world surrounding it.

- And of the recent attention Neimeth’s work has garnered? “It’s just so rewarding to do all this in my own backyard – in my little chicken coop.”

- In renovating the structure, Neimeth’s goal was to “bring the outside in. It makes me forget that I am in the city.”

- Neimeth’s 48-inch outdoor installation, “Raku Nests”, adorns the yard.

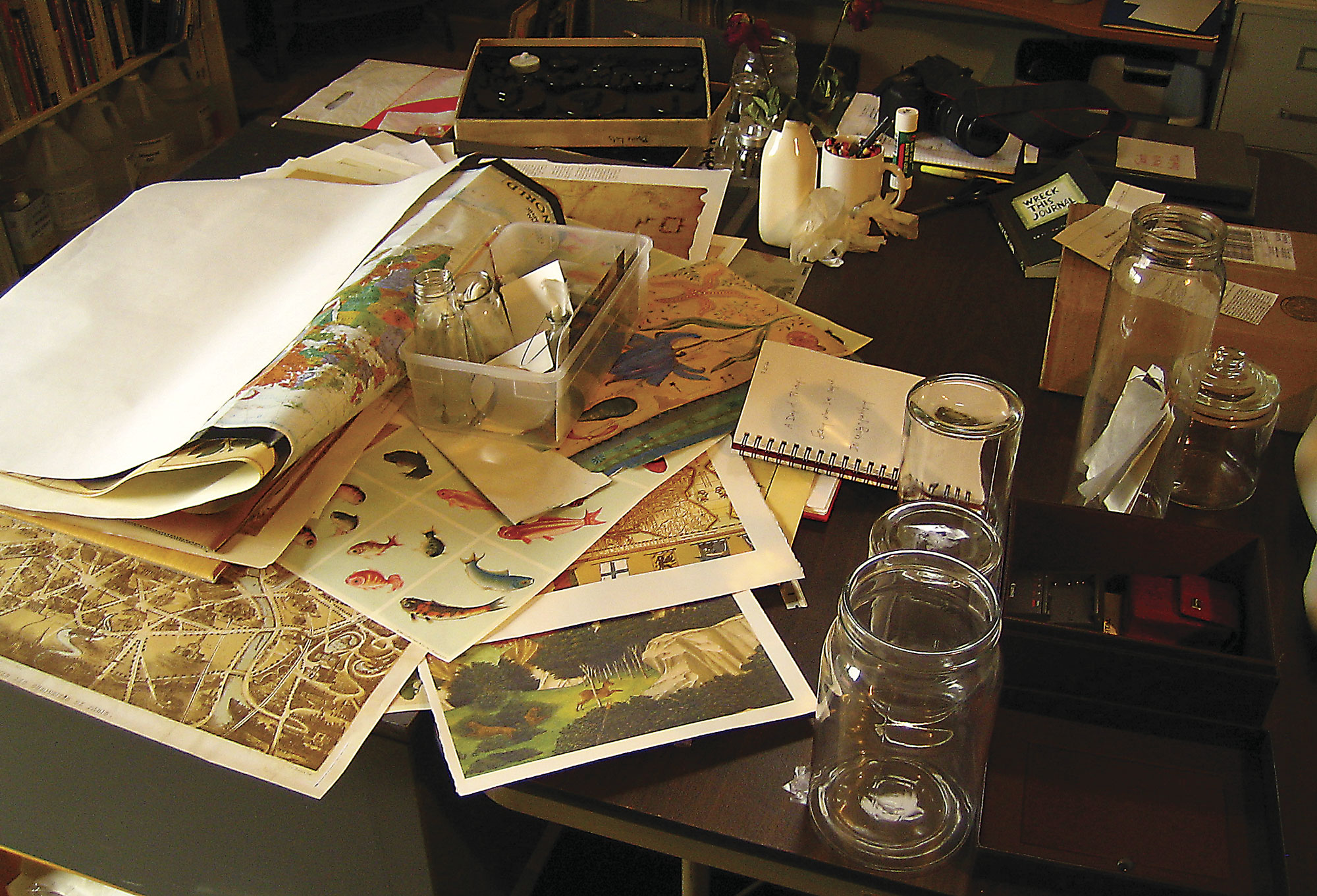

- The studio is filled to the brim with a visual cacophony of collected objects, curios, iconic miniatures, clay and kiln-ready pieces.

- “It really is my creative think tank …it is a retreat for me – a mental refuge of sorts,” says Mary Daniel Hobson in her studio.

- Situated in the center of an acre of flat land – only moments from the beach – is Hobson’s studio. Painted “barn-red” to match her home, the studio maintains its original structure – a simple wooden building belying the streamlined workspace within.

- Neimeth champions a “slow dish” movement: “It is nice for people to eat from something so special yet so functional.”

- While creating an efficient workspace, Hobson remained attuned to her process – the attic space was reconfigured to house a meditation area.

- The artist’s materials are strewn throughout the studio.

No Comments