30 May In the Studio: Michael von Helms

To get to Michael von Helms’ studio, I weave through the sharp, steep turns north of Santa Fe and into the heavily wooded foothills of Tesuque, cross a babbling creek, turn onto an unpaved road and climb toward paradise.

The 69-year-old von Helms, looking relaxed in turtleneck, jeans and weathered, handmade cowboy boots, greets me in front of the home he shares with his partner, fiber artist Nancy Paap. Standing in front of his studio, with its northern New Mexico-style pitched metal roof, he points out a spectacular view of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. From these serene surroundings, he then leads me into his studio — and complete disarray.

“I’m chaotic,” he says. “There’s just no other way around it.”

His studio has a garagelike quality, 1,000 square feet, white walls, 20-foot-high ceiling with open trusses and five large skylights, and cement floor, stained by dripping paint. Dozens of open paint cans cover a table, littered with old paint brushes. “I move from brush to brush,” he says. “I buy cheap brushes. I buy tons of them.”

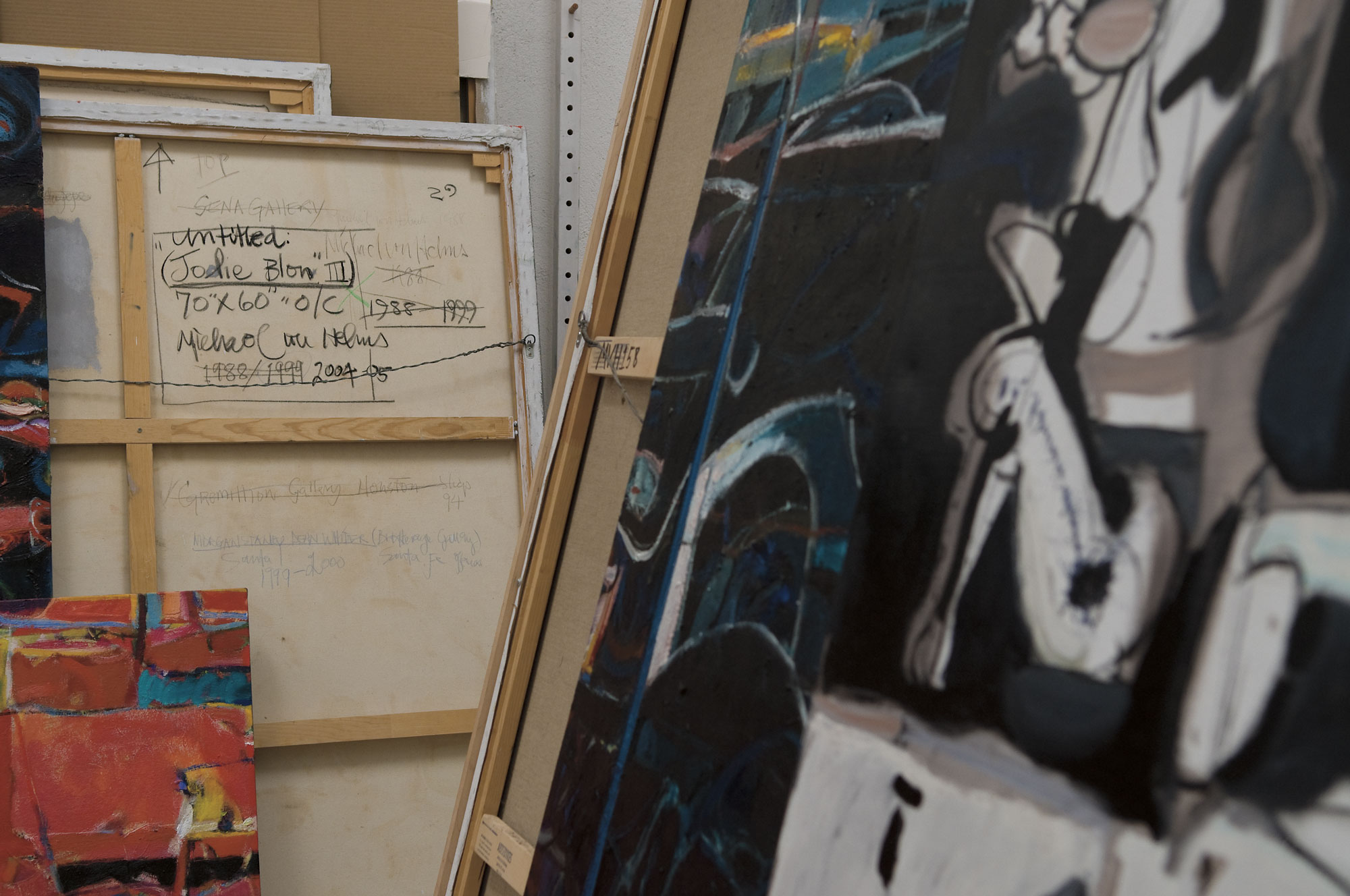

Scattered across the room, stacked against the walls, are probably 40 to 50 canvases — with perhaps another 20 or 30 in the hallway connecting the studio to the house. His desk is cluttered with books and notes, and on his bookshelves I find titles ranging from All About Fences and Gates to Richard Diebenkorn in New Mexico.

This place is far removed from the natural beauty outdoors, and to keep it that way (and adjust the light), cardboard and plastic are tacked over the glass doors, and most of his windows have been blocked by cut pieces of Insulfoam.

Yet there’s a method to all this madness.

“My studio feels more like a workplace to me if I don’t bring much of the outside in,” von Helms says as we move up the steps and down the hall toward his kitchen for coffee. “In the studio, I plug up all the windows because some people have asked me, ‘Don’t you just love it? Don’t you just want to get out in nature?’ And for me, my life and my devotion is in artistic resolutions that come from within. The beauty of the land really interferes with me, but I appreciate it.”

Which is obvious from his art.

“Some of his paintings are like watching a tightrope walker,” says Lawrence Matthews, executive director of Deloney Newkirk Fine Art, which has two locations on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road. “You’re thinking, ‘Man, if that painting went one more way, it would just fall off the canvas.’ It’s just absolutely fantastic.”

A nonfigurative Abstractionist, influenced by Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Joan Mitchell, Pablo Picasso and Jackson Pollock, von Helms didn’t start out as an artist. Born in 1939 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, von Helms moved to Santa Fe after World War II, and was supposed to follow in his parents’ academic footsteps. Instead he bolted east and later to Houston, Texas, working as a photographer for 25 years. But art called to him and one day he handed his studio keys to his assistant and returned to New Mexico, abandoning photography for large-scale oils on canvas.

“Like a lot of abstract painters, I came into the world as a quote-unquote mature guy,” he says. “I was in my 40s when I started painting.”

By the late 1980s, he was showing at the Gerald Peters Gallery before chaos and divorce left him pondering his future.

“Everything I had, I lost a lot of it,” he says. “The art took it away, if you will.”

From 1995 to about 1998, von Helms left art behind and worked in construction. “I was a little bit of a loose cannon,” he says, “and had to reground myself.”

He began dating Paap, and when he decided to return to painting, he worked in her small tool shed until his studio — large, like a photography studio, but with a ton of light — was completed in 2001.

“I was different,” he says of his return. “I didn’t have the money to throw at abstract work, so I had to be careful. But art was not so much a choice as it was an obsession.”

He spends five to eight hours painting in his studio daily, repainting each work three or four times, sometimes more, and if it doesn’t work, he might let the painting sit for years before coming back to it.

Disorder helps.

“I find it’s hard to settle down and work and work,” he says. “I have to work with chaos on my palette. That’s kind of who I am. You don’t want to settle down. The crazier the stuff is, the more hopeful it is.”

Johnny D. Boggs is a Santa Fe-based writer who has won three Spur Awards and the Western Heritage Wrangler Award for his fiction. His novels include Northfield and East of the Border, and he has also written about art for several magazines. His website is www.johnnydboggs.com.

- Nonfigurative abstractionist Michael von Helms took a break from painting for about three years before returning to large-scale oil-on-canvas.

- Typically, von Helms says he’ll clean his studio once a year. Otherwise, he creates better when he is surrounded by chaos

- Oil paints lure von Helms because of their “viscosity and sensuality and surface.”

- Doors are shut, windows are often boarded over to keep out any unwelcome distractions when von Helms is at work in the studio.

- The studio is attached to the Northern New Mexico-style home he shares with fiber artist Nancy Paap.

- Paintings often sit in the studio for years. “If it doesn’t work, you have to let it sit,” he says, “and it talks to you, or you rethink it.”

No Comments