04 Apr In the Studio: Richard Parish

Richard Parrish’s fused glass art studio is about more than color — it’s about texture and surfaces, layers and patterns. Jars filled with sandlike hues, others crammed with pebbled nubs of tones, nearly every available shelf and work-bench fans with glass in its many forms. From rods to sheets to frits and powders, he pulls all these and more into his emerging palettes.

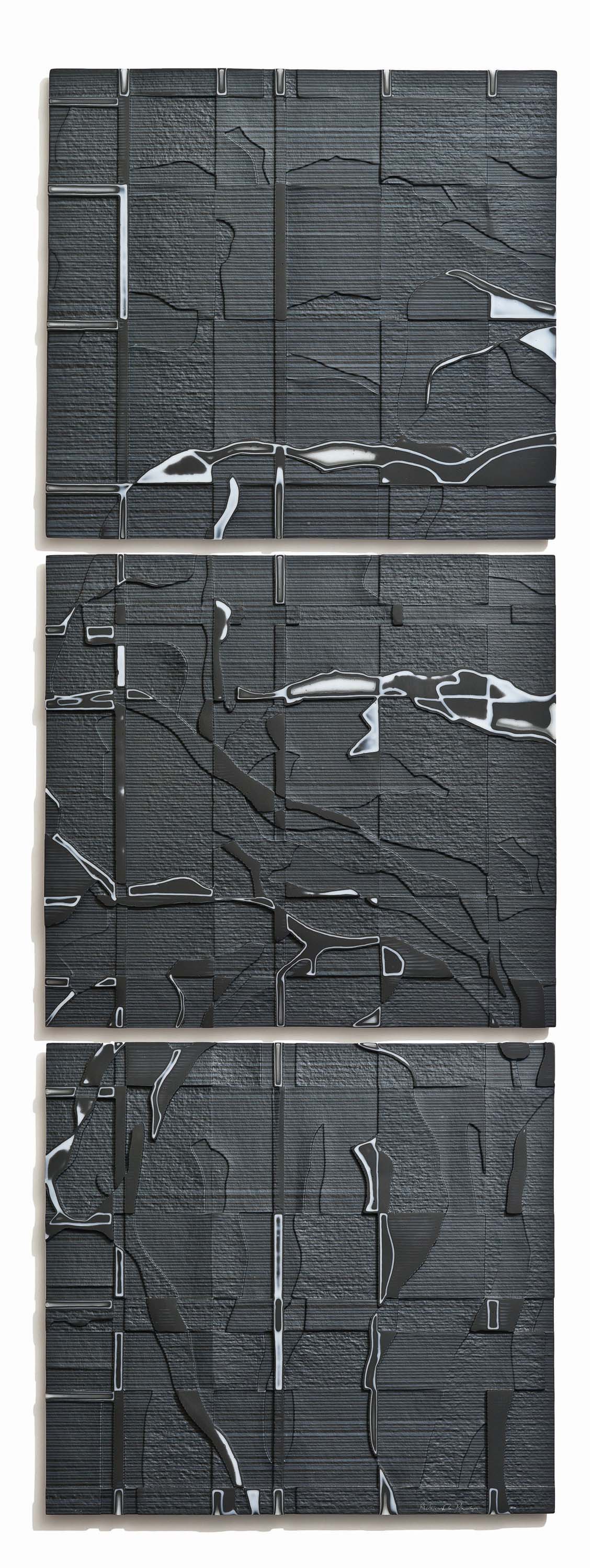

Parrish, a glass artist at the forefront of his field, works on a piece — the first of a triptych — that is slated to be one of the focal pieces in a traveling exhibit underwritten by Bullseye Gallery, in Portland, Oregon, a premiere glass art gallery. His recent work brings together the idea of place, geometry and mapping as well as an exploration of the spirit. Using layers upon layers of kiln-fused glass melded onto a silica fiber sculptural form, Parrish then mines parts of the piece to unearth the layers below.

“It’s a metaphor for looking under the skin,” Parrish says, as he dons a pair of safety glasses and picks up a grinder in his Bozeman, Montana, studio. “What’s under the skin? Everything that makes up who we are.” The layers represent not only what we see and what we don’t see, but it also asks the viewer to think about what can be revealed.

As with Parrish’s bas-relief sculptures, his 1,600-square-foot studio outside of town has grown along with his methods. The large utilitarian space with concrete floors and overhead lighting houses several long tables to accommodate his various simultaneous projects.

Parrish’s large kilns reach up to 1,500 degrees and buzz quietly along one wall. Glass rods, sheets and jars on metal shelves line the opposite wall. The smooth lines of his studio, the clean spaces and open worktables with jars of knives used to cut the glass, and extra lighting for the close-up work give Parrish the blank slate he needs for his complicated pieces.

What we don’t see are the sketches, the first step of the bas-relief sculptures. These are Parrish’s quiet beginnings, something he likes to keep to himself. Yet his progression is evident in an array of pieces hanging in the studio that span the last decade of his work, a fascinating study of his evolution from architecture professor to student to world-renown workshop instructor with his glass sculptures.

His studio space is a reflection of his commitment to never stop growing and to exploring his medium.

Parrish remembers growing up on a farm, watching his father cut through hills and spread out the earth over the lava fields of Idaho. This idea of rows cut by natural rock formations against that which is manmade is reformed in these sculptures.

The grinding, or the discovery part, as he calls it, demands that he be open to the process.

“I create a shell and then I pick pieces off, maybe sift some more powdered glass onto it and fire it a few times,” he says, between bouts of scouring off layers, revealing hidden treasures of color or clear glass, like a window, within the piece. When the silica fiber has been removed and the pieces have been fired several times, what’s left is a rough bas-relief in black and gray.

On a nearby table, Parrish has the other two parts of the triptych laid out. He’s decided on what needs to be subtracted, which lines will continue through the pieces and which will not.

After he’s turned off the water and unplugged the grinder, the piece, 17 inches square, is brought over to the sand blaster.

Looking through the window of the blaster, Parrish concentrates the high-power sand particles on the target areas, as the silica carbide hisses through the pneumatic hose. He flips on the vacuum. When the sculpture comes out, the top layer looks weathered like rocks on the hillside, roughened and aged.

Parrish’s work has gained international recognition, and he teaches workshops around the U.S. as well as across Europe in this, his own technique for creating bas-relief sculptures in fused glass. “As I developed this style and attended a few other workshops, I began to get a good idea of what I’d need to accomplish the kind of art I wanted to make.”

From there, his studio began to teem with more tools, more ways to get to the ideas that lived in his head. In addition to the sand blaster, he added diamond-padded grinders and a few more shelves with metal ledges to show his pieces.

At the thickest point, the triptych will be five-eighths of an inch, but when looking at it from a distance, lined up vertically, it appears much deeper. It really is a study of negative space.

Parrish opens a cabinet beneath his workbench, a peek into what we don’t see when we walk into the studio. Tucked into the drawer are 200 or more squares of inch-thick glass tiles.

“These are my samples,” he says, picking one up. The sides reveal several colors and patterns caught inside the glass, like tiny moments in time. “I just like to experiment with techniques to see what happens.”

It is this ability to experiment — to grasp at an idea and to be open to the results — that has set Parrish apart.

“I’ve always loved bas-relief, everything from the Egyptians to more modern times,” Parrish says, lining up the three panels as they will appear when mounted on the wall. “I’ve been playing with ways to look at these pieces … maybe from eye-level on a pedestal as if looking across the land.”

Like an inventor or a conjurer, Parrish contemplates the possibilities. So much of what makes him a great artist is reflected in his workspace: the hidden drawers of samples, the layers of glass both opaque and translucent and the open worktables ready for what’s to come.

- “Tapestry” | Kiln-formed Glass Triptych | 27 x 59.75 inches

- ”Red River” | Kiln-formed Glass | 9.75 inches

- “Place: Displace” | Kiln-formed Glass Triptych | 48.24 x 17 x .75 inches

- Parrish’s studio contains an ample supply of colored sheet glass; thick slabs of colored glass; hues of shards; jars of pulverized frit.

- Parrish uses his sifting method to lightly dust a piece with color.

No Comments