17 Nov In the Studio: We're All in this Together

He paints his bears with human eyes, an autobiographical nick or scar added to each nose. There’s an intended portrait-like quality to his paintings — beseeching, quiet, calm — as if you’re in the presence of a specific individual. “Look at me,” they implore with a steady gaze, “I am unique. Important.” Written on one frame are the words, “Not About Black Bears,” which is where things really begin to get interesting.

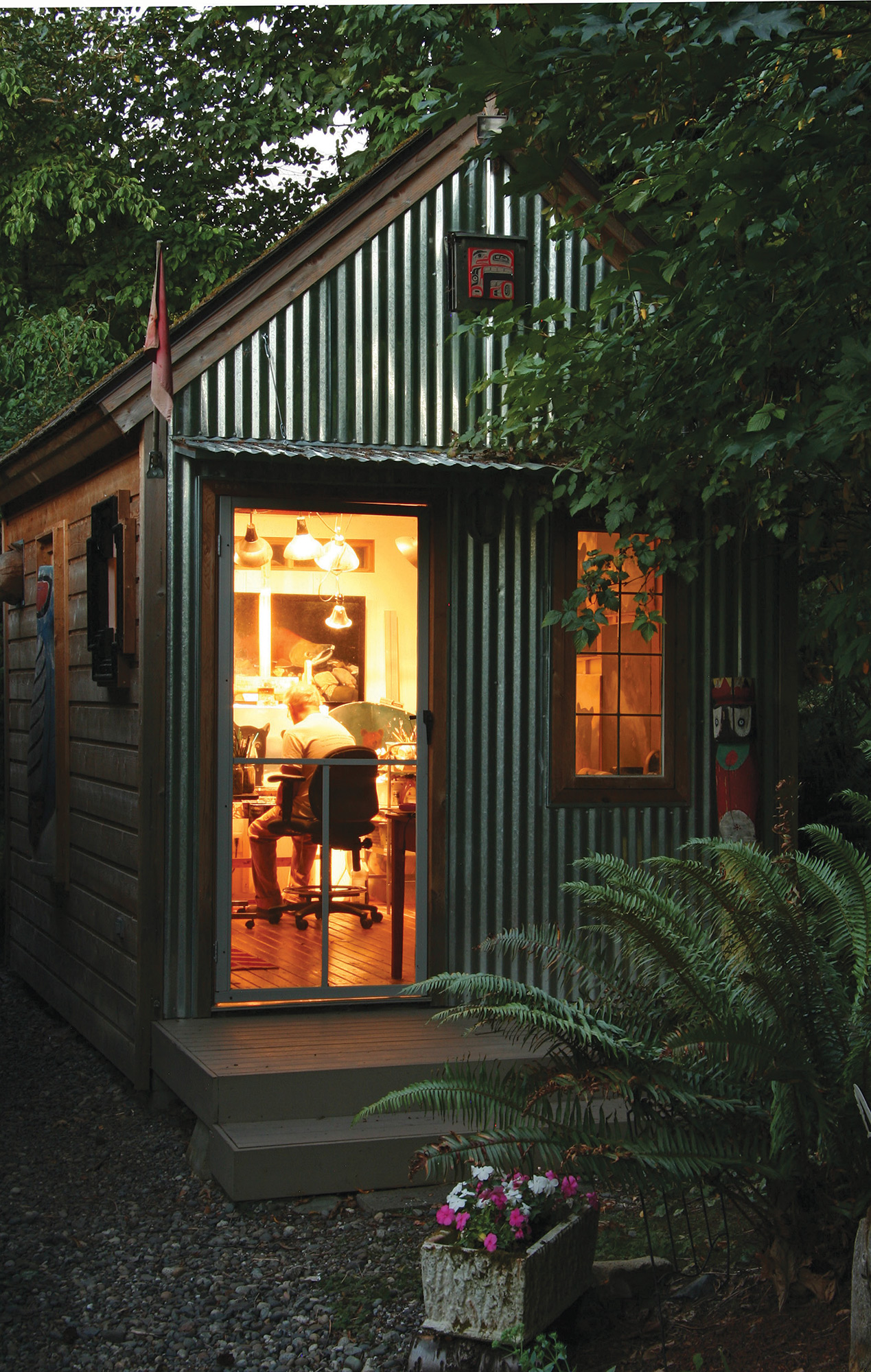

On the day I visit, a dozen bears, a zebra, a sea turtle and a snowy owl occupy the walls of Robert McCauley’s 9-by-14-foot studio. Set on an RV pad next to his garage in Mount Vernon, Washington, the cedar and tin-sided structure looks barely big enough to store his brushes. But once inside, it’s surprisingly spacious, thanks in part to a 12:12 pitch roof and the judicious use of windows. Modeled on the shotgun shacks of the South and the more recent tiny home movement, McCauley built the studio himself. “There is an exhilaration,” he says, “of having built it the way I wanted it.”

Part of the way McCauley wanted it was decidedly different. He may have the only cedar tongue-and-groove floor in the history of studios. Cedar is notoriously soft, easy to mark or scratch. “That’s what I ended up loving about it,” he says. “It had this mark-making quality, this patina that takes on so quickly.” If that wasn’t enough, cut into the floor is a replica of a Geological Survey marker, the kind you find on mountaintops. In this case, the arrow for Washington’s Desolation Peak points at his easel.

With the exception of a 2,500-square-foot studio he rented in Rockport, Illinois, McCauley has always worked in small spaces. In one infamous case, his studio was a basement where he mistakenly built a sculpture too large to carry up the stairs. Taking a sledgehammer to his labors notwithstanding, McCauley says large spaces make him lose contact with his work; he feels he can get too far away from it. That is not the case here. If McCauley steps back nine paces from his easel, he can get a fair view of the canvas. If he steps back 10, he’s out the front door.

McCauley grew up in Mount Vernon and earned his bachelor’s degree at Western Washington University and his master’s degree at Washington State University. After graduation, he went directly into teaching and spent 35 years at Rockford University in Illinois where he ultimately became the chairman of the art department and earned fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Illinois Arts Council. Raised in soggy Mount Vernon, however, with wild nature as companion, mentor and friend, McCauley never cottoned to the Midwest’s idea of beauty.

“Nature is really a force here [in the Pacific Northwest]. Out in Illinois, nature is pretty benign. It’s like Abe Lincoln’s new hatchet. It’s got three new handles and two new heads. There’s nothing left of the original. I never got used to it as long as I was there.”

That being the case, the fauna of the Pacific Northwest makes up the bulk of McCauley’s work, but he balks at the idea that he’s a wildlife artist. A wildlife artist, he says, is determined to recreate a carbon copy of their subject, right down to each hair or tree leaf. McCauley is all about fuzzing the details and taking liberties with the actual. He paints species that could never exist together as a harbinger of global climate change. He’ll paint a zebra upside down to illustrate humankind’s relationship to nature. “We’re all in this together, you know,” he tells me.

And what did he tell his students?

“You are obligated as an artist to add to this civilization, this culture. You don’t have to solve the problems, but you can raise the red flag if there is a problem, keep reminding people of what is going wrong. It doesn’t obligate you to have the answer to it, but it’s still your job.”

For McCauley, the job part of painting requires discipline. He paints every day from 4 a.m. to 4 p.m., no matter what: Christmas, New Year’s, if flying to Los Angeles, California, that day. Ritual (and dare I say superstition) enters into his process as well.

Each morning when McCauley enters the studio, he turns on the lights but avoids looking at the canvas. Next, he crosses the room (eyes still down) and turns on another set of lights, walks back, sits in his chair and — this I like — greets the other paintings. “Hello, guys,” he says. Only then does he allow himself to look up and see if his current work is “where I thought it was when I turned off all the lights last night.”

Not surprisingly, McCauley works from a palette that is decidedly Pacific Northwest. Earth tones and mashed potato skies are a given. But McCauley doesn’t paint simply to create beauty, which he does; he paints to convey thoughts. “I see paintings as being very conceptual, not just paint and canvas,” he says. “I’m trying to rewrite the history of the way man and nature had first contact. I’m a revisionist historian. Revisionist painter.”

Revisionist or social commentator, painter or prophet, McCauley is a writer at heart. He points to a framed picture of Dylan Thomas’ tiny writing cabin on the wall. During our four-hour conversation we talk books as much as painting: Moby Dick, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Diary of an Edwardian Lady. He is also revising a book of personal essays about his life and art and is a voracious reader.

That said, having positioned himself as one of the premiere Northwest artists, he’s not interested in reinventing himself. McCauley takes solace in the solitude and silence of his surroundings and the compactness of his studio, a place where he finds painting, like words, are plastic. “But the thing that isn’t so plastic,” he says — steady gaze, black bear honesty, sea turtle grin — “is bravery.” A quality it is doubtful he has ever been without.

- Just one of many personal touches, a carved bear’s head looks out from the back of the building over the forest.

- A tiny replica of the Queen Mary was recently inserted into a porthole window. McCauley’s daughter, Robin, was married on the Queen Mary this past summer.

- A pair of shed caribou antlers grow mossy outside of McCauley’s studio. The poet Billy Collins calls McCauley’s work, “literal and symbolic at the same time.”

- Light illuminates a work in progress inside McCauley’s studio. His second-grade teacher once said, “Robert will never do anything creative.”

- Over time, McCauley has become known as “the bear guy” for the expressive, sensitive portrayals of black bears he paints. “Sometimes I think of them as selfportraits,” he says.

- Embedded into the floor of his studio is a replica of a Geological Survey marker pointing to Desolation Peak. True to McCauley’s sense of humor, it points to his easel.

- Located just a few feet from McCauley’s house and tucked into the trees, the artist says he “built this studio as a sort of hideout.”

- McCauley got his work ethic from his father, a carpenter. He paints every day from 4 a.m. to 4 p.m., no exceptions.

No Comments