30 May In the Studio: William Matthews

If a home is a reflection of those who dwell in it, an artist’s home — whether an urban loft, a seaside shack or a grand manor — is a vivid expression of his influences, experiences and passions. It puts on display his true artistic self while serving as a constant source of inspiration.

“What I love about houses is seeing people’s personalities coming out,” says painter William Matthews, “particularly if they have some sense of aesthetics but don’t use a decorator. They fill where they live with experiences they’ve had over a lifetime. That’s what I try to bring to the places I inhabit.”

Matthews’ home, guest house and studio, located at 8,000 feet in a Ponderosa pine forest in Evergreen, Colorado, serve as a showcase for his many collections, all of which speak to his upbringing, his extensive travels and his various passions. From antiques (a 17th-century Ming painter’s table here, an Amish rocker there) to folk art (including a 100-year-old model of a Galway hooker, a boat that carried turf between Irish islands), and fine art representing many cultures, eras and styles, unique collectibles are literally too numerous to count. In this way, Matthews’ home and studio serve as canvases for self-expression. And the objects within them, in turn, fuel his own artwork.

Matthews paints every day. When he’s not traveling abroad — to Asia or Ireland, to name some recent destinations — he takes long road trips to places like the Gamble Ranch, a vast, traditionally run cattle outfit in northern Nevada. He gathers material by riding with cowboys, painting en plein air and photographing constantly for later reference when back home in his studio.

Situated just yards from his house, Matthews’ studio was designed by his brother, New York architect Peter Matthews, and built in 1983. “It’s simple, light and airy,” says the artist. “It has a loft and big windows to the south/southwest and north. I’ve been painting in it for 28 years. It’s served me very well.”

More recently, Matthews decided he and his children had outgrown the property’s original two-bedroom cabin. Working with architect Bill Poss of Aspen, Matthews designed a classic yet unique shingle-clad mountain home that makes the most of its rugged site while beautifully showcasing his collections.

“Having grown up in the Bay Area, I was most influenced by Arts and Crafts architects like Bernard Maybeck and the big shingled houses around where we lived in Pacific Heights,” recalls Matthews. “Maybeck used different materials; he had no problem mixing modern with traditional, or organic with inorganic. I love shingles, particularly in double courses, particularly the big, heavy ones. I’m always amazed people don’t use them more in mountain vernacular. They are so beautiful, particularly as they age.”

Matthews oversaw three months of blasting on the steep hillside, chose and placed all the stones used in construction and spent hours determining the siting of the house amidst the property’s 300-year-old pines. “The trickiest part was getting it sited, then figuring out where the main living spaces were going to be and how the light would affect them. The windows are carefully set so direct sun doesn’t shine on the art. Watercolors are very fragile and I wanted to hang art guiltlessly.”

Hang art he did. And guitars, antique shovels, old posters, Navajo rugs. And that’s just on the walls. Everywhere the eye lands there is something fascinating to discover. In the living room alone, he says, “There are George Carlson bronzes, kachinas, masks, pots and baskets. I collect old mahogany boxes and English watercolor sets. There are a lot of antiques, including an 1830s William IV architect’s desk, a Windsor chair and leather furniture. There’s a Kiowa cradleboard, a Thomas Jefferson bust, a Shaker bucket, a Scandinavian spinning wheel, an Irish potato spade, a Japanese carved eagle and eaglet, a red deer antler rack, a concertina, a diaphonic accordion and a pair of lights made out of call horns from a fire brigade. The Frederick Waugh oil painting was my grandfather’s. There’s a Fritz Scholder acrylic, a Frank Schoonover bucking horse gouache and a 15th-century German Renaissance painting.”

Every room is a repository for fine art, vintage lithographs, old tools, Native American artifacts, Argentinian quirts, antique signs, masks, models, textiles, books and musical instruments. And for this artist — who dropped out of high school to pursue careers in music and art, who attended art school briefly, then lit out for Europe with only $1,000 and ended up staying for five years, and who has traveled the world over — every item has significance.

“Through all that early part of my life,” Matthews recalls, “it really was about collecting material and interest, and getting an idea of what’s out there to come back to the West with a broad view. To me, what makes art interesting is the panorama, that broad view.”

In most interiors this would be all too much clutter. But Matthews’ artistic eye and meticulous attention to detail translates to refined, richly layered interiors. From whole roomscapes to tiny vignettes, each room, each corner, offers a feast for the eyes. For the artist, each serves as a catalyst for his own work. “Some of these links can be inspirational in ways you don’t expect.” he says. “Influences can come from places that are unpredictable.”

Matthews’ influences have been both unpredictable and not; he has been surrounded by artists his whole life. His father ran the San Francisco office of an international advertising agency. His mother, Joan Matthews, was a portrait painter. “When we were growing up,” he recalls, “my mother was always teaching us to look at what was around us. It made us aware of the world in ways others were not. She was always talking about shadows and light. I intuitively say the same things to my kids, which they hated, but now appreciate.”

All of Matthews’ siblings and children are artists. Kim Matthews Wheaton is a landscape painter, while Carrie Nowell, is a designer and ceramicist who also styles houses. His brother, Peter Matthews, is an established architect in New York City. Matthews’ son, Austin, is an artist-in-residence at the San Francisco Zoo and teaches graffiti in East Bay public schools. His daughter, Alistair, recently completed her studies at the Chicago Art Institute.

Works by family members mix happily with Matthews’ eclectic collection throughout the three buildings. Along with paintings by his relatives and old photographs of his grandfather are a Picasso lithograph, artworks by E. Irving Couse and Clyde Aspevig, an Andrew Wyeth watercolor (sent by the artist to Matthews on his 50th birthday), Yoshida woodblock prints, Edward Borein drawings, 18th-century erotic Japanese brush paintings, Edgar Curtis photographs, Maynard Dixon drawings, World War II food posters (“Food is ammunition. Don’t waste it.”), a Jo Mora conte drawing of a Hopi woman, Welsh landscapes, scrolls of calligraphy, paintings by turn-of-the-century California artists and “a bunch of things I brought from China.”

Matthews is a self-described high-energy person. When surrounded by meaningful things, he is ever buzzing with ideas for the next painting, the next trip, the next project.

“I am a victim of the affliction that runs through our family,” he admits. “Everything around me must be beautiful and stimulating. We artists are collectors. And you get to a certain age and all of a sudden you are surrounded by years of experiences, and the artifacts that connect and remind.”

Chase Reynolds Ewald covers the West Coast for Western Art & Architecture. Her most recent books, New West Cuisine and The New Western Home, showcase the food and architecture of the Mountain West.

- William Matthews is at home surrounded by art.

- The artist’s octagonal study features paintings by family members, and a steeply pitched “witch’s hat” ceiling.

- The artist’s shingle-style mountain home is located at 8,000 feet in Evergreen, Colorado.

- A hallway is anchored by an arrangement of Native American beadwork and Navajo weavings stacked in a rice basket Matthews bought when visiting a small Chinese village. Matthews has painted the same grain elevator for 25 years.

- William Matthews the musician collects instruments; William Matthews the artist displays the most sculptural ones as artworks.

- Next to Matthews’ bed, a painting by landscape artist Paul Henry hangs over a German Black Forest antler table.

- A quiet corner juxtaposes a watercolor by Pennsylvania artist John McCoy with an 18th century Windsor chair and Northeast Indian paddles.

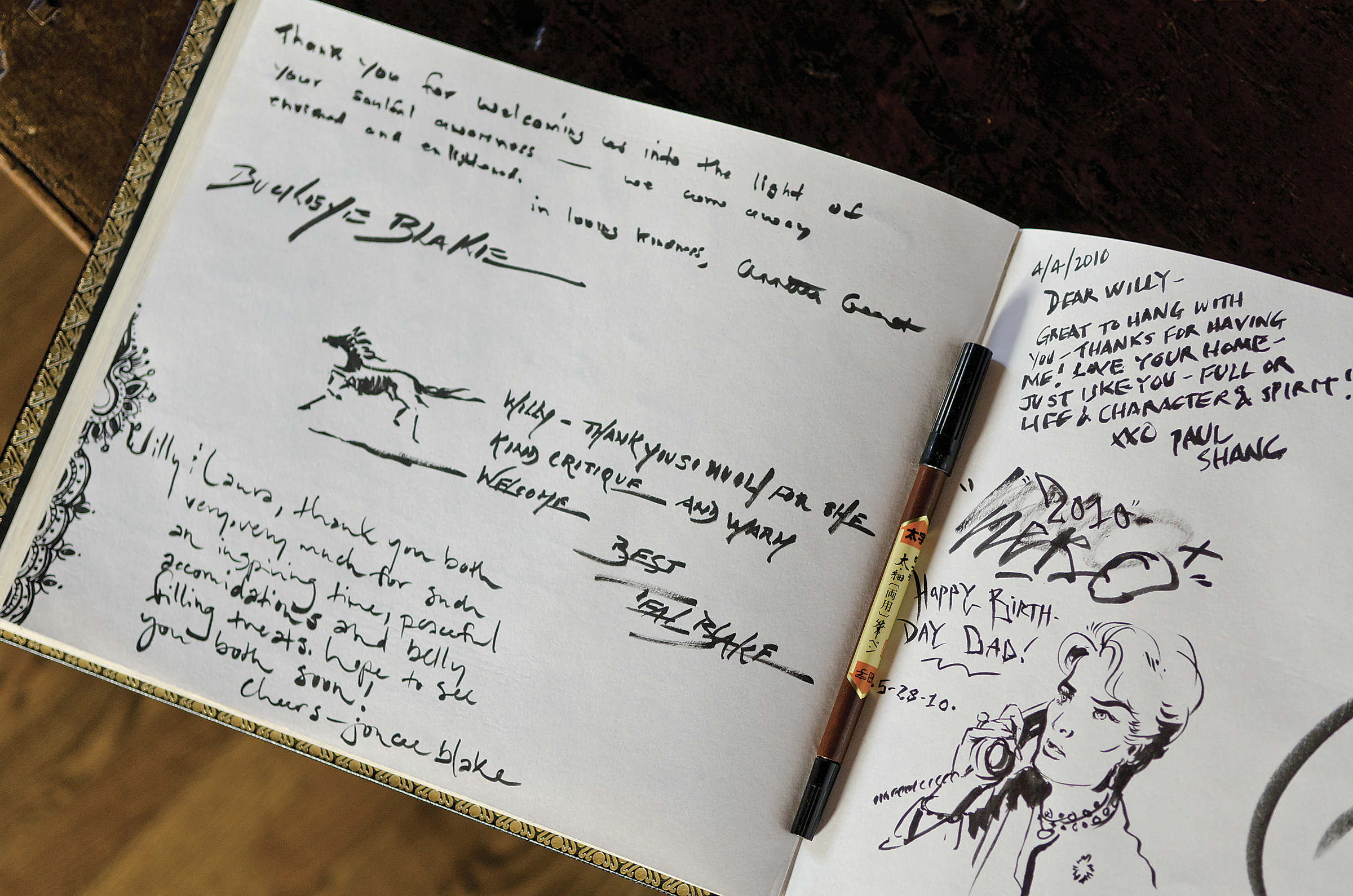

- With many artists among his family and friends, Matthews’ guest book is itself a work of art.

- In the warmly hued kitchen, paintings by 19th and 20th century California artists are grouped on one wall, while World War I posters, enamel signs and 1960s Sierra Club posters complete the space

- The Great Room in Matthews’ self-designed home was patterned after that of a manor house in Scotland. This warm and inviting room — full of antiques, books, fine art, and comfortable furniture — features a vintage French-Canadian canoe, iron chandeliers from a Great Camp in the Adirondacks, and a George Carlson bronze, Searching the Wind, resting atop a fireplace constructed of rocks from the property.

No Comments