24 Jul In The Studio: Scott Christensen

It is an acutely bright spring morning at Scott Christensen’s studio near Victor, Idaho. Outside the north wall of high-set windows, a deep blue sky holds ebullient clouds. In all directions, fields of brilliant snow roll away like a giant canvas awaiting paint. It appears that way until Christensen — his teaching skill evident — points out the texture and color in the seemingly monochromatic snow. He sees the beauty and more, because he’s practiced at looking. His eye has been in training for 25 years, driven by his tenacious desire to paint. This keen perception he translates into luscious yet economical landscapes that beg to be explored. Though finished at the easel, most begin as plein air studies. “I love being outside, and if I can’t be outside I’ve got to feel like I am,” Christensen says in reference to his 1,200-square-foot studio.

The studio could easily be dubbed his playing field, for the core of this 48-year-old artist’s character developed playing football. Although he walked away from the game after a spinal injury sidelined him in college, Christensen’s iron-pumping determination is the reason for his success. Now, after decades focused on capturing the beauty of the natural world, Christensen is reflecting on how athletics shaped his philosophy as an artist.

Standing at his easel, his palette at waist height, the 6-foot-tall Wyoming native paints in a flurry of motion. He’s warming up, setting his pace to the mellifluous voice of Italian opera star Cecilia Bartoli on an iPod. In his left hand he wields a paintbrush as deftly as a fencer on attack. His movement is a progression of decisions: He might shift the color of a sky, or define the edge of a riverbank, then with the meat of his fist blend away the entire scene.

“I’m not trying to make a painting yet, I’m trying to get the concept,” Christensen explains as he mixes muted yellows and greens from a palette limited to primaries, white and a few pre-mixed grays. He’s doing a practice study on a scrap of canvas, but it’s serious business. The ideas he works out now will inform the tonal painting he will tackle later. Tonals are particularly difficult because the color values are close; there is little difference between the lightest light and the darkest dark, which means that subtlety is key. Christensen cites Bartoli as an example: “She has a lot more range in her voice and you can tell she could just cut loose, but she’s keeping it within that real tight range. I love that control.”

Christensen might rework one tonal painting numerous times. He’s a perfectionist under the influence of a highly developed inner coach, but he understands the fundamentals. This preparation for what he calls “painting at the highest level” began late in college. His persistence led him to workshops with artists Bob Barlow, Clyde Aspevig and William Reese, but he credits studying the masters in books and museums for his primary education. Christensen has learned that painting is all about relationships. For example, in composition one must consider not just the tree but the shape of a tree as it relates to the sky. Colors, too, are connected. “Color can’t stand on its own; it’s always the color next to it that affects it,” he says. “It’s the juncture that requires the most thought.” Once he establishes the relationships, then he can paint the painting.

It’s no surprise that studies precede paintings. Christensen keeps them as idea seeds the way writers keep sentences that will lead to essays, or musicians keep melodies that foster songs. What is surprising is how many of the finished pieces hanging in the gallery adjoining his studio are there simply as reference. Framed works in progress also adorn the walls. None are for sale. “The good news is, Kristie sold all the new work, the bad news is, there’s no new stuff,” says Christensen apologetically, referring to Kristie Grigg, his wife and business manager. Her considerable marketing talent, coupled with his well-established reputation, means that pieces sell the minute they’re available.

The crux is it may take many months before he considers a painting finished. “That’s why this building,” he says. It’s a place to let paintings cool off. When a painting is problematic he hangs it on the wall and walks away. “I don’t allow myself the luxury of solving problems right away,” he says. “I let the painting tell me what it needs. It sounds hocus pocus, but it’s not, it’s taken me years to get to that.” If he pushes too hard, then the original idea may be lost and the piece fails or becomes a different painting entirely. “I’ve done that so many times that I had to get tired of it.”

It was some years ago that Christensen grew tired of forcing his creative process. He was living in Jackson, Wyoming, was hugely successful, painting profusely, gaining collectors as well as prestigious gallery and museum invitations, but his art was suffering. “I was just trying to produce paintings, not doing fine work,” he admits. To paint at the highest level he had to slow down. So in 2007 he bought land and built a studio, which, true to its Craftsman style, is as beautiful as it is utilitarian. It’s the embodiment of what he needed as a mature artist, a place offering space and time, a solo playing field.

The studio may be the manifestation of his process, but it took being reunited with his college football teammate Chris Carlisle, now training coach for the Seattle Seahawks, to make clear just how deeply athletics informed Christensen’s work ethic. In a YouTube video Carlisle and Seahawks coach Pete Carroll discuss the game. “See those drills they’re doing?” Christensen asks. “That’s what I was just doing. The game starts when I put up the canvas.” By that point he knows where he wants to go. He’s done all his prep, practiced his tones. “It’s then you can run out and say, ‘Okay I’m ready!’” Each time he approaches a canvas, the game is on.

His friendship with Carlisle has given Christensen fresh enthusiasm to communicate his craft. He’s a born teacher and each year dozens of people attend his workshops. Recently, for an instructional painting video starring the artist, filmmaker Tony Pro captured the men discussing their philosophy. In a nutshell: You have to prepare at the highest level so you can practice at the highest level, so you can play at the highest level. It’s the tension between success and failure that keeps them in the game.

Christensen has obvious talent, but as an athlete he learned to do it until he mastered it. “We’re born with a gift, but then it’s a matter of the want-to,” he says. The trick is to figure out how. “If a tree doesn’t look right, you try to solve the tree,” he says. “When it’s actually something around it that’s going to solve that problem.” In life, as in painting, Christensen believes that in the end it all comes back to mastering relationships, and that takes practice. The pay-off is his fully developed relationship to beauty.

Seonaid B. Campbell has passion for the arts and life science, which she explores through writing, documentary filmmaking and as a naturalist guide. She recently worked on the show “Who Do You Think You Are?” for NBC. Her Gaelic name, pronounced Shona, comes from her family in Scotland.

- Christensen’s works hang in his gallery.

- “Color can’t stand on its own,” says Christensen, at work on a new painting.

- “Clean Air of Autumn” | Oil on Canvas | 40 x 48 inches

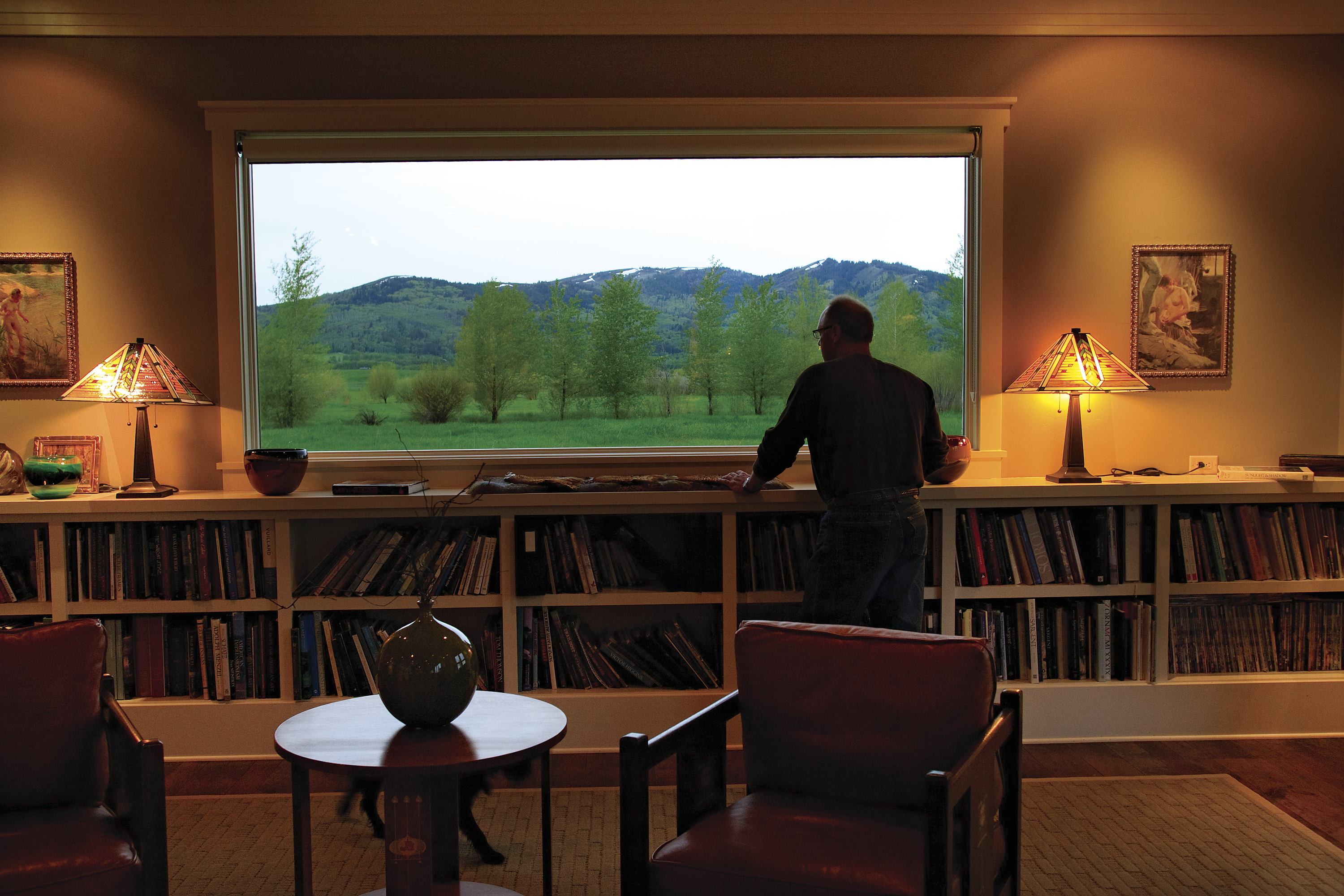

- Christensen works in his reference library.

- The spring-fed pond next to his home provides the artist solace and inspiration

- “Marsh Evening” | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 12 inches

- Above the studio/gallery are guest accommodations.

- In Christensen’s studio, he has space to step back and critique a painting … or toss a football

- The artist works at his hydraulic easel while Molly, the English Cocker Spaniel, waits at the door.

No Comments