01 Sep Collector's Notebook: Original Prints

At a time when one-of-a-kind paintings by signal Western and wildlife masters like Frederic Remington and Carl Rungius are fetching sums that start in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, scores of savvy art scholars, gallery owners and collectors are eying with renewed interest the market that specializes in original prints.

Printmaking — including etching by use of copper or zinc plates, lithography tied to limestone plates, and woodcuts — occupies a heightened position in the oeuvre of select artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, like John James Audubon and John Edward Borein, even as it served as the early profession of landscape giant Thomas Moran.

Those methods of limited reproduction — usually in the dozens rather than the hundreds — bear little resemblance to techniques of today, such as giclee prints, which rely on archival quality ink-jet printers and can be produced in mass quantity.

Instead, the printmakers of the past authorized a limited edition of prints, frequently hand-signed, sometimes hand-colored, influenced by an overarching desire to share their artwork with more than a single collector.

“The motivation for many artists was to keep the stamp of originality on the work and remain directly engaged with it,” said Michele Senecal, executive director of the International Fine Print Dealers Association. “It was a powerful tool for disseminating images but it also was a way for people who liked the work to own it.”

Where an artist’s talents and appeal were superior, original prints enhanced popularity and provided modest to handsome income. Where prints by top Western painters might in their day have sold for $5 each, the same works today might cost thousands.

In the 19th century, prints represented an early — and crucial — method for reaching a mass audience at a time when original artworks were a scarce commodity, said Ron Tyler, the recently retired director of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

Lithography arrived in America in 1820, revolutionizing printmaking. Its advent would lead to the opening of a market for original prints at a time when technology and periodicals provided venues for images even as they fostered an audience eager for them.

And the government would play a role, with exploration of Western lands triggering publication of books containing several hundred prints in editions that could number as high as 50,000.

Although Audubon came too late to the American West to realize his dream of documenting the region’s animals, the arc of his career as an illustrator and a painter is pinned to prints produced in the 1830s that in some instances represented the original work of art.

“Audubon produced prints with a team: He would draw animals and assorted other artists would provide the background or landscape,” said Tyler. “In those cases, the lithographer would combine those unfinished works to create a print, which did not exist as a finished art piece until then.”

It is not merely the beauty of a piece or the stature of an artist that determines whether an original print will gain in value. Art experts are reluctant to apply hard-and-fast rules when it comes to predicting the price of 19th-century and early to mid-20th-century prints, saying instead that the desirability of an image, its condition and rarity dictate worth.

The prints of a leading 19th-century and early 20th-century painter of Western landscapes, like Moran, who began his career in a wood-engraving company, would at first glance appear valuable.

But even larger size prints of Moran’s elevating Mount of the Holy Cross, a much-admired painting of a 14,000-foot peak in the Sawatch Range in Colorado, may be worth as little as $100 if it represents an etching that first appeared in a magazine and was widely reproduced. Yet another version reproduced from a copper plate etching and slightly larger in size is quite rare and would be sure to garner steep bids at auction.

By the early 20th century, prized Western images by Remington were reproduced prolifically, with Collier’s Magazine offering separate, mail-order sales of so-called prints dubbed “artist’s proofs,” despite the fact they were reproductions with a simulated signature, according to the Frederic Remington Art Museum in New York.

Christine Brindza, acting curator of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, said a wholesale industry has been shaped around Remington reproductions.

Outside of glutting the market with images of modest price, the publishing and reproduction of works by Remington and Moran brought the vision of that faraway region into focus for Americans elsewhere.

“Images of the West came right into living rooms; it gave people a different way of viewing the world,” said Brindza.

Rungius, celebrated for paintings of Western wildlife in a career that spanned the first half of the 20th century, authorized in etchings no more than a couple dozen images in editions limited to 20 or 30, said Harry Cohen, owner of Harco Gallery in Tucson, Arizona.

Cohen, who specializes in 19th- and 20th-century American art, said original prints by Rungius, unlike the artist’s paintings, remain within reach of the collector of middle income. For example, a 1939 8-by-11-inch etching depicting mountain goats and signed by Rungius is priced at $9,500 at Harco, compared with the hundreds of thousands it might cost for an original oil.

That compares with John Edward Borein, a largely self-taught illustrator who worked California cattle ranches in the late 1900s and whose artworks were first printed near the turn of the century.

Borein’s etchings of Western figures such as bronco busters and American Indians were prolific, one reason prints are priced in the modest range today. “I love his art, but it’s hard to sell because there is so much of it,” said Cohen.

Art dealer and author Gary Temple, co-owner of Meadowlark Gallery in Billings, Montana, is among experts who urge would-be buyers of original prints to first ensure authenticity and then trust in their taste. With just a small percentage of the art market holding value, Temple advises collectors to purchase what they love.

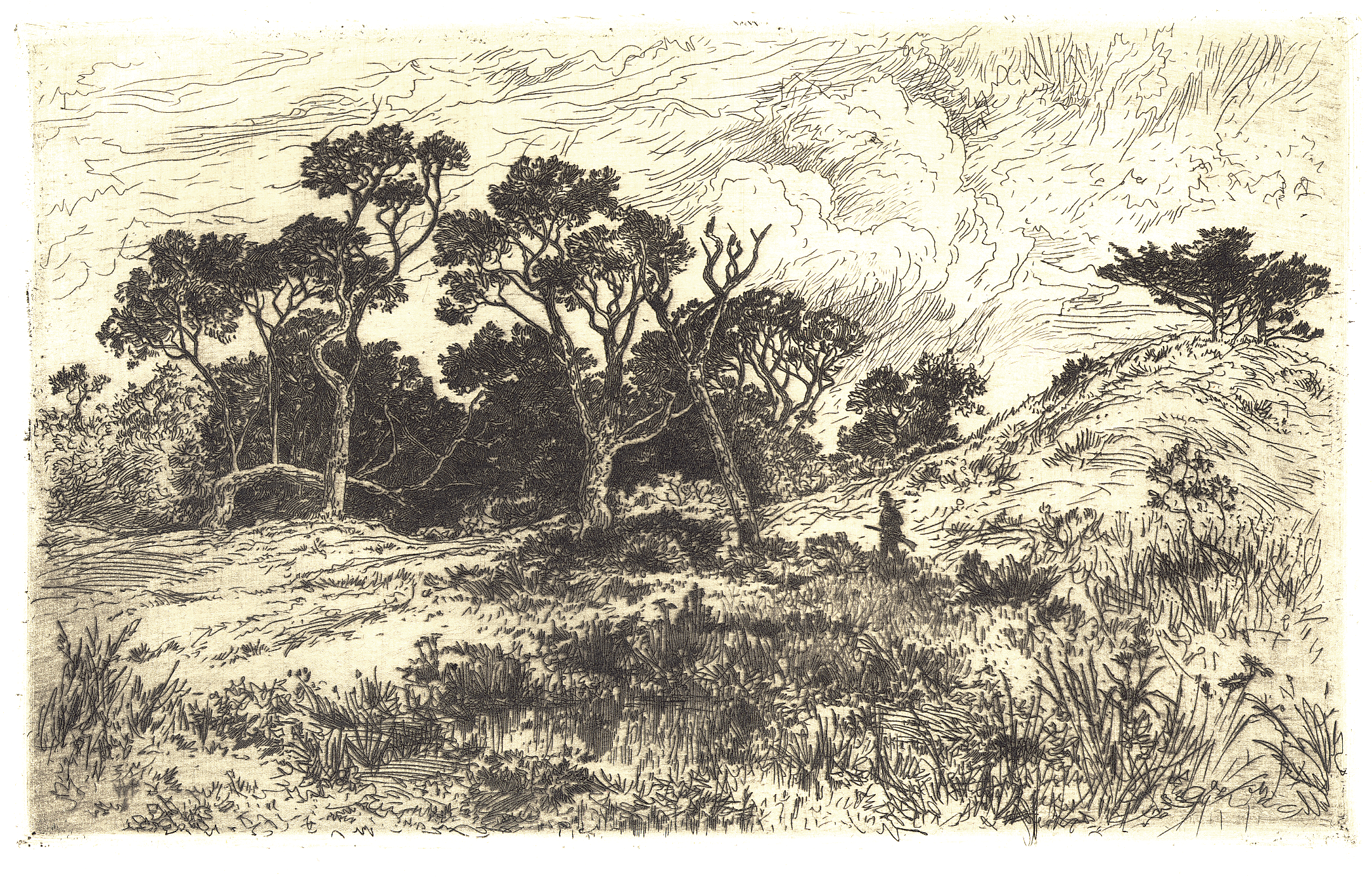

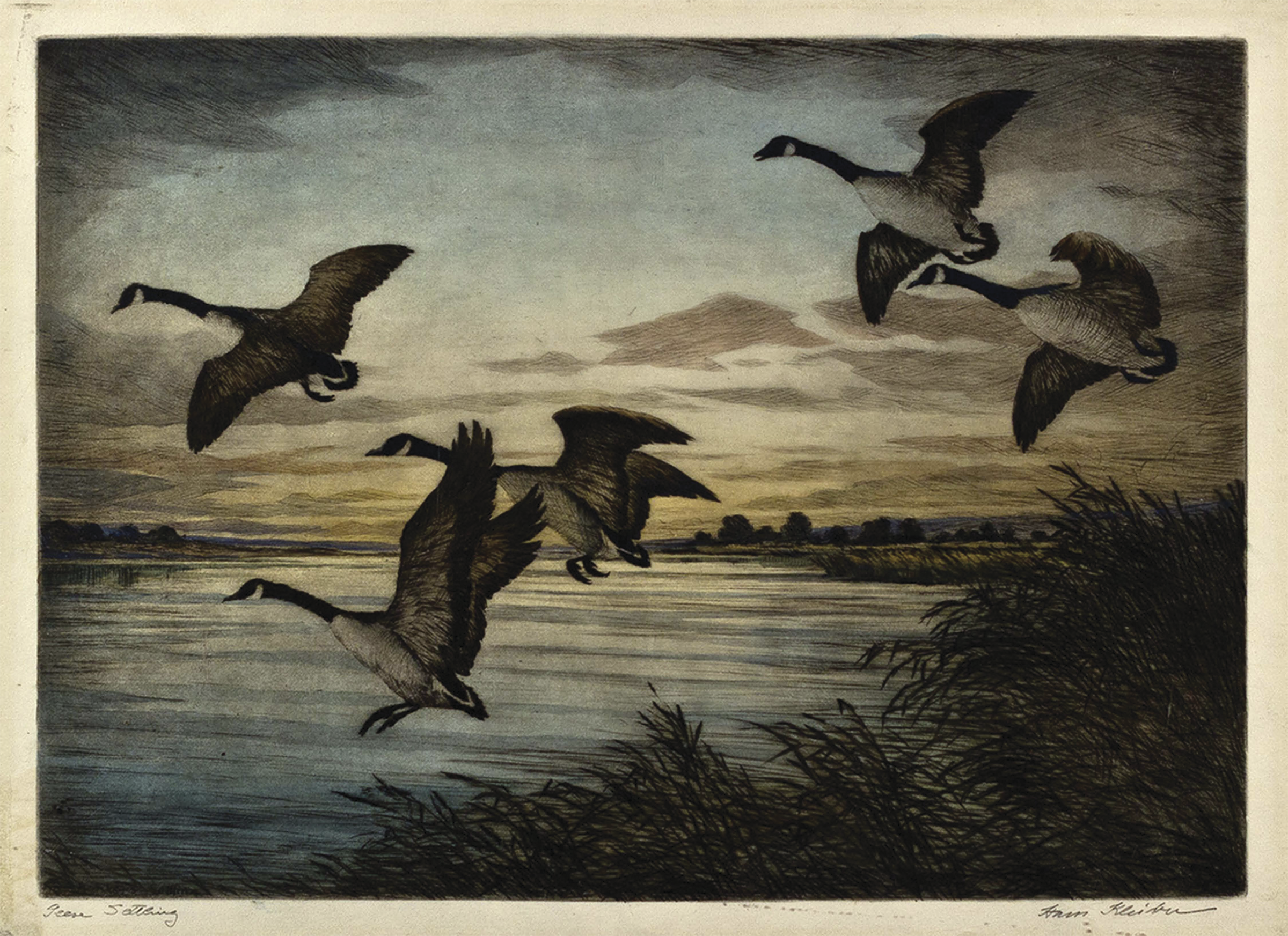

That practice has worked nicely for Temple, who began collecting pieces by Hans Kleiber — mostly etchings but also paintings — because he was so drawn to the Wyoming forest ranger-cum-artist’s precision and integrity.

In a career covering most of the 20th century, Kleiber produced hundreds of etchings, many exhibiting the remarkable delicacy of Cedar Waxwings, a print the size of a postcard that has the power of an outsize oil to attract the eye. Temple says Kleiber did not track the number of prints; rather, he produced them until, as the artist described it, the plate went blind.

While prints by Kleiber have steadily climbed in cost — selling for $9 in the 1920s, rising to $60 in the 1970s and on up today — Temple refuses to dishonor a favored artist by evaluating his works in dollars and cents. “Let’s talk about what that artwork is and who the artist was; what it is selling for now is not a good approach,” said Temple.

Laura Zuckerman lives and writes in Salmon, Idaho. Her work has appeared in such publications as The New York Times, Scientific American and Cowboys & Indians.

- Hans Kleiber, “Range Horses” | Etching | 3.75 x 5.75 inches | courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

- Hans Kleiber, “Geese Settling” | Etching | 9.75 x 13.75 inches | Courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

No Comments