19 Oct Perspective: Beatrice Mandelman [1912-1998]

When young artists Beatrice Mandelman and her husband, Louis Ribak, left New York City and moved to Taos, New Mexico in 1944, they traveled part of the way from Santa Fe by narrow-gauge steam train and the final miles by stagecoach. Heading north, the coach topped a rise overlooking the vast, open Taos Valley and spectacular Rio Grande Gorge and then descended into the town of Taos. Years later Mandelman recalled being captivated by a place where horses were tied to hitching posts on a plaza surrounded by earth-colored adobe houses, and the sound of English mingled with Spanish and the ancient language of the Taos Pueblo Indians. She and Ribak had stepped back in time.

But the modern world, including the world of Modern art, was beginning to find its way to Taos in the mid-20th century. And in the following decades, Bea and Louie, as they were known, would be highly instrumental in shaping the art scene of their adopted home. Conversely, the visual vocabulary of artists who settled there was powerfully shaped by the clear light and stunning landscapes of the Southwest, the region’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, and the freedom from entrenched East Coast social structures offered by this wild, unfettered place.

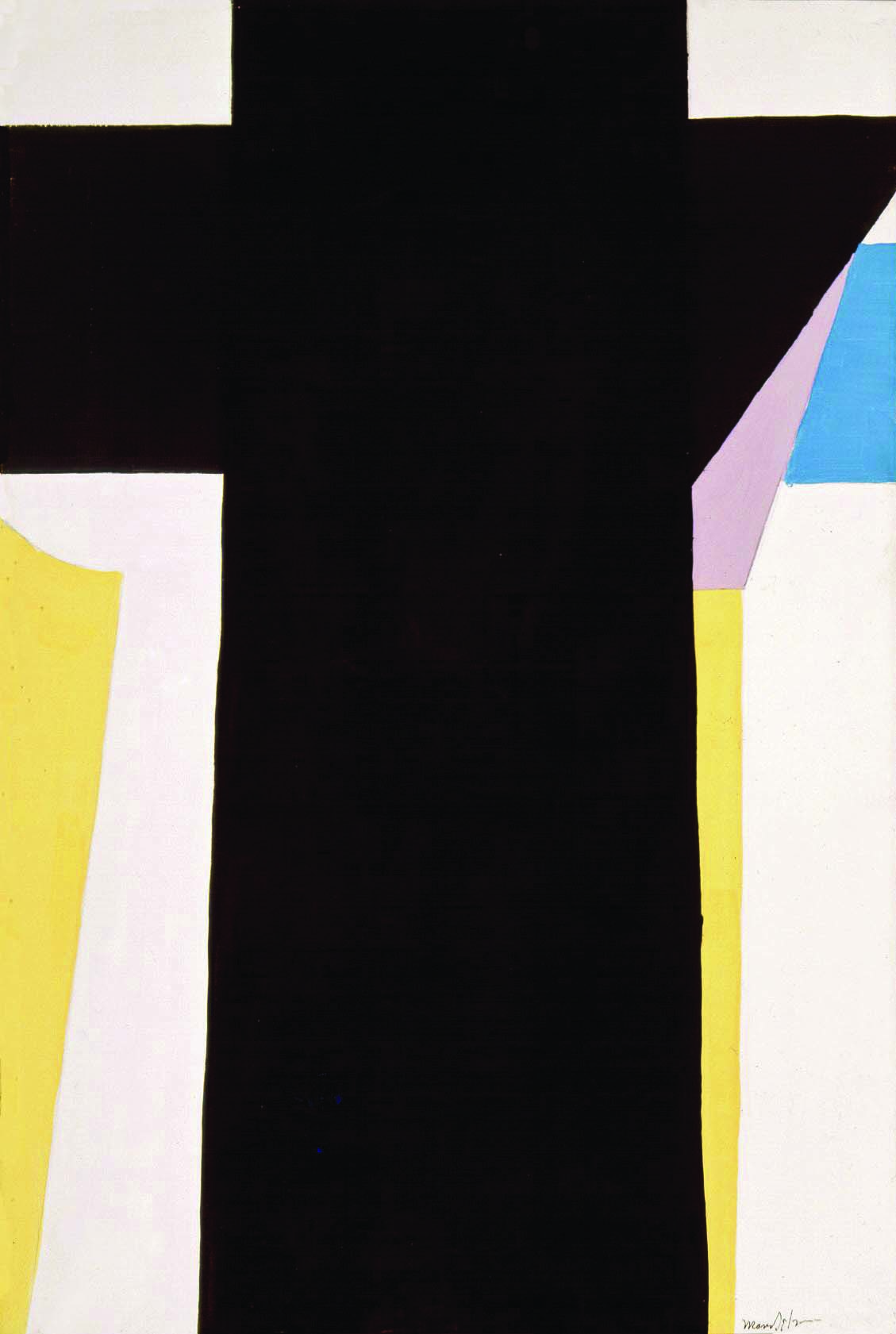

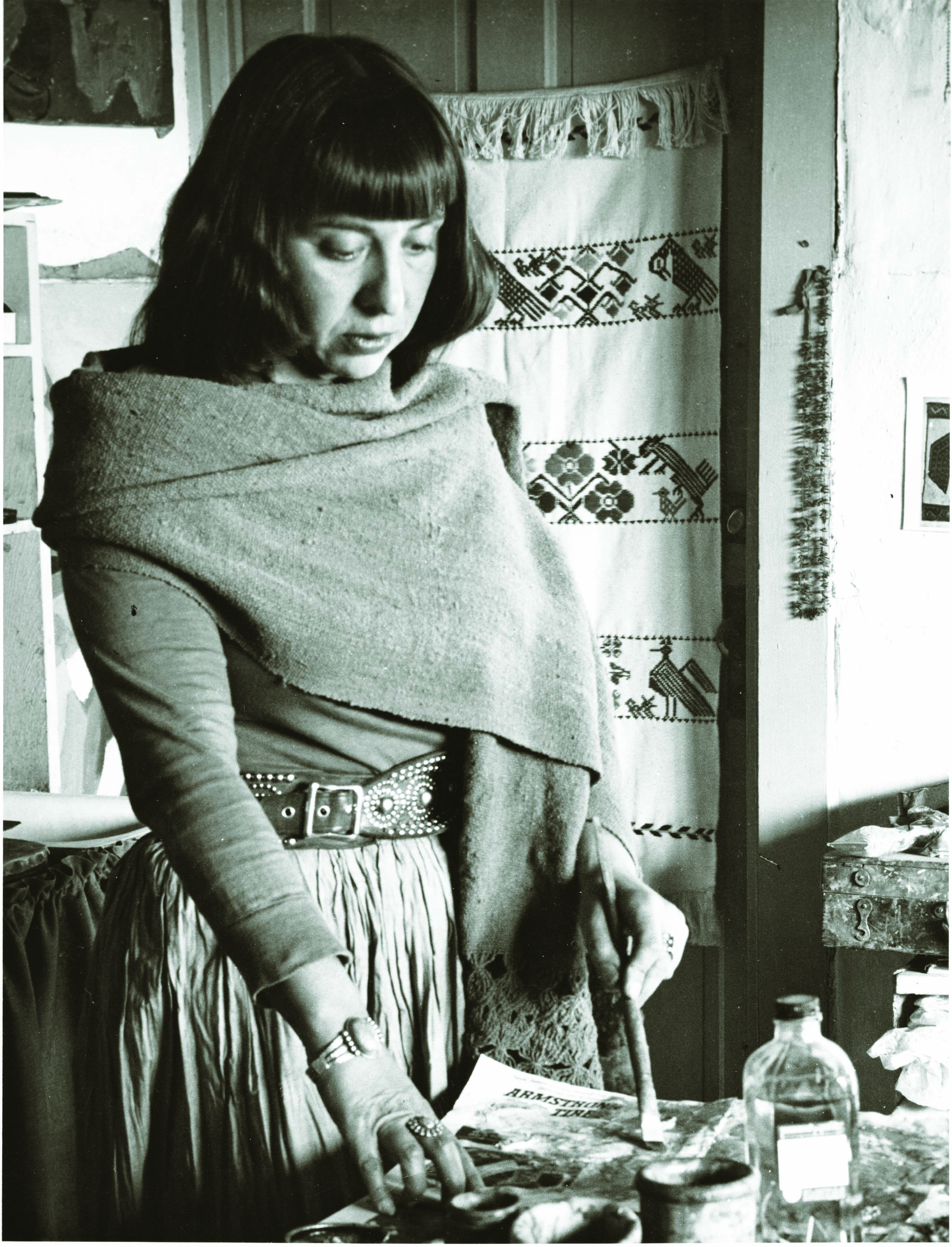

For Bea, dark-haired and short in stature but big in personality, Taos provided a creative and personal freedom well suited to her enthusiastic, adventurous, opinionated and endlessly curious nature. And while in some ways she believed her work did not receive the critical acclaim it deserved, being removed from the New York art scene allowed her Modernist vision to develop in its own distinctive way. Her early artistic influences — including Social Realism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism and European Modernism — melded with the openness of the Southwest to create a playful, lyrical abstraction whose aim, she once said, was “to convey joy, love, song, dance.”

Bea Mandelman was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1912, the daughter of first-generation Jewish émigrés from Austria and Germany. Even as a young girl, she was driven by a passion for art that defined her until her death in Taos in 1998. At age 12 she began taking classes at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art, later also attending Rutgers University and the Art Students League in New York. In the early 1930s she was introduced to Cubism and soon became acquainted with such vanguards of New York Modernism as Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock and Stuart Davis.

It was a circle of artists who, true to the times, allowed women to sit in on lively discussions but did not welcome female opinions or consider them artistic peers. The shadow of a male-dominated art world in the mid-20th century hung over Bea in Taos as well. But in the spirit of other strong female artists who found their voices in New Mexico — Maria Martínez, Georgia O’Keeffe, Agnes Martin and Florence Miller Pierce among them — she flourished.

In 1935, during the height of the Depression, Bea was hired by the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) as a muralist and then a printmaker in New York. Her art from this period reflects an interest in progressive social and political causes that stayed with her throughout her life, but which primarily remained under the surface except in a series of anti-war-themed collages she created in the 1960s during the Vietnam War. She worked for the WPA until it disbanded in 1942, the year she married painter Louis Ribak. By then her art had been part of important exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Bea later explained the couple’s 1944 move to New Mexico by expressing dissatisfaction with the rift between Social Realism and Abstract Expressionism in New York. The trip also involved a visit with Louie’s teacher and mentor, painter John Sloan, in Santa Fe. But David Witt, art historian, former curator at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos and author of two books on the Taos Moderns, has uncovered evidence of another motivation for the couple leaving New York. In the early 1940s, Louie’s association with left-leaning artists resulted in harassment by the FBI — harassment that followed him to New Mexico. In documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, Witt learned that within two weeks of Louie and Bea’s arrival in Santa Fe, the house where they were staying was ransacked, perhaps by an overzealous volunteer associated with the FBI. Shortly afterward, the couple moved on to Taos.

In the 1950s the long arm of McCarthyism reached into another area of their life when an FBI informant attended the Taos Valley Art School, founded and run by Louie and Bea. The school was subsequently forced to close after losing its GI Bill funding, through which many artists studied after World War II. The informant would become notorious for providing false information to the House Un-American Activities Committee and eventually was convicted and jailed. Alexandra Benjamin, executive director of the Mandelman-Ribak Foundation in Taos, believes the FBI experience “left Bea fearful. She didn’t know what trouble could come of talking about it, so she didn’t.”

When Bea and Louie arrived in Taos, Thomas Benrimo and Emil Bisttram (a part-time resident) were among the only local artists working in Modernism, and no Taos galleries were showing Modern art. The Taos Valley Art School became a significant factor in changing that. Along with the town’s low cost of living and its geographic location as a stopping point on the way to Mexico, the school attracted a convergence of New York and San Francisco Bay area artists ready to step out of the mainstream art milieu.

Just as importantly, Bea and Louie served as a social hub for an informal group of artists who began calling themselves the Taos Moderns. Key members of this group, along with Louie and Bea, were Edward Corbett, Agnes Martin, Oli Sihvonen and Clay Spohn. For a time Gallery Ribak, in the couple’s home, hosted shows by the Taos Moderns.

“Outside of New York and San Francisco in the early 1950s, there was probably more interesting Modern art going on in Taos than anywhere else in the country,” notes Witt. These artists did not abandon their urban core, but reworked it aesthetically in response to the stimulating new forces they experienced in New Mexico. Bea’s later impact on younger artists “was not stylistic, but more personal,” observes Joseph Traugott, curator of 20th-century art at the New Mexico Museum of Art. “They didn’t mimic her style but were influenced by her drive, passion and energy.” That passion contained “kaleidoscopic enthusiasms and vaulting international ambitions,” in the words of art critic MaLin Wilson-Powell. It helped produce a prolific body of work over the decades, including paintings, collages and prints.

Surprisingly comfortable in relatively primitive settings, Bea soaked up Spanish-speaking culture in Taos and Mexico. Beginning in 1948, she and Louie spent virtually every winter south of the border escaping the high-altitude, northern New Mexico cold. (Once in the 1940s, Bea and English-born artist Stella Snead hitchhiked from Taos to Mexico.) In 1948 Bea lived in Paris for a year to study with French Modernist Fernand Léger, where she became friends with painter Francis Picabia.

Along with extensive travel in Turkey, Greece, Africa and South America over the years, these experiences brightened Bea’s color palette and gave her abstract compositions a joyful sense of slightly off-kilter musicality. She also forged a lifelong friendship with Agnes Martin, which resumed when Martin returned to Taos following a long stint in New York. The two women worked in very different styles. Yet as “far and away the most important and powerful female artists in Taos at the time,” according to Witt, they no doubt drove each other to greater explorative heights.

After Louie’s death in 1979, Bea remained in Taos. Battling cancer for the last 10 years of her life, she surprised friends and collectors by rebounding several times and spent time in her studio every day until the last few weeks. In May, 1998, two months before she died, her life and work were featured in an article in Forbes magazine, providing not only a sense of validation regarding her place in the larger art world, but also bringing a flurry of international interest and sales.

Alexandra Benjamin was working daily with Bea at the time, inventorying and cataloguing the artist’s lifelong body of work. Benjamin remembers Bea’s intense pleasure at finally achieving the recognition she desired for most of her 85 years. Yet another kind of recognition seemed to emerge at the end of her life as well.

“She realized that all along she really had what she wanted: She had the life of a painter. All she wanted to do was paint,” Benjamin relates. “It was a very complete life. There were a lot of waves along the way, but she ended up on the shore where she wanted to be.”

- “Untitled’ | Gouache and Collage on Paper | 1958 | 25.5 x 19 inches Courtesy of the Mandelman-Ribak Foundation

- “Black Cross” | Oil on Canvas | 1966 | 35.25 x 23.75 inches | Collection of the Denver Art Museum

- “Untitled” (Free Speech) | Mixed Media Collage on Cardboard | c. 1960s | 23 x 18 inches | Collection of the Hardwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

- “New York No. 52” | Acrylic on Canvas | 1994 | 40 x 60 inches | Collection of the Hardwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

- Bea Mandelman c. 1948, courtesy the Mandelman-Ribak Foundation

No Comments