17 Nov Perspective: Belmore Browne [1880–1954] and George Browne [1918–1958]

When George Browne was 15, he decided the best use of his time would be to quit school and dedicate himself to drawing and painting. His parents, surprisingly, agreed. “That’ll be fine,” his father said.

What this meant was that George would study art under his father in an intensive regimen of eight hours a day of instruction and practice, six days a week. George happily complied. For years already, he had been accompanying his father, painter Belmore Browne, on camping, hunting, fishing, sketching and painting trips into the wilderness beyond the family’s remote log cabin near Banff, Alberta, in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. George could have no better teacher.

Belmore was an accomplished, formally trained landscape and wildlife painter and an extraordinary outdoorsman and mountaineer. His consuming passion was the wild, which he explored and experienced in almost every conceivable way, including as part of the first expedition to summit Mount Olympus in Washington and in the first attempts to climb Alaska’s Mount McKinley (now Denali) in 1908, 1910 and 1912. While the final attempt was turned back by dangerous conditions just 300 yards from the summit, it is acknowledged as a significant moment in mountaineering history. A few years later, Belmore testified before Congress as part of the successful effort to create Mount McKinley National Park, established in 1917.

Embodying true pioneering hardiness, survival knowledge, discipline and a spirit of adventure, Belmore spent weeks at a time rafting, dogsledding, panning for gold, hunting whale and seal with the Aleut, tracking bear and, beginning in 1902, taking part in expeditions in Alaska and Canada to collect mammal specimens for the American Museum of Natural History. All the while he sketched and painted what he saw, bringing home materials for producing larger works. He painted outdoors in the Canadian winter in temperatures down to 30 below, wearing three layers of wool socks over his hands and holding his paintbrush pushed through the fabric.

In all ways, George benefitted from his father’s dedication to and knowledge of the outdoors and art. Beginning at an early age, the younger Browne was immersed in both kinds of activities, eventually combining them in sought-after oil paintings of wildfowl and, to a lesser extent, large mammals in their natural habitat. Yet following a 1958 shooting accident that took George’s life at age 40, a number of decades passed and his and his father’s artistic reputations receded from public view. Then an excellent 2004 book by John T. Ordeman and Michael M. Schreiber, Artists of the North American Wilderness: George & Belmore Browne, helped spark a revival of interest in both artists, which has continued through increased exposure and sales of their work.

“Both Belmore and George were true wildlife painters. Their work is authentic because of the great deal of time they spent in the outdoors, time spent watching big game animals and birds in their natural settings. They went out and got their own reference material, and in order to be the very best, a wildlife artist has to do that,” notes Curtis Tierney, fine art dealer and owner of Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman, Montana, who has sold work by the Brownes for 16 years. John Ordeman, who has extensively written about American sporting artists, describes Belmore in his book as “among the first and the most important painters of Alaska and the western Canadian provinces and the animals native to the region.”

Belmore’s early years provided a supportive foundation for the interests that would follow him through his life. Born in 1880 to an old New England and New York-based family whose wealth was acquired through business and finance, he grew up primarily in the Pacific Northwest, where his family owned a lumber operation. He and his two older brothers were sent back East to boarding schools each fall — Belmore to Connecticut — and spent every summer sailing on Puget Sound and fishing, hunting and camping in what was then unspoiled territory near Tacoma, Washington.

At age 18, inspired by both parents’ avocational interest in painting, Belmore decided to seriously pursue art. He moved to New York City and lived for two years with an artist friend of the family while taking courses at the New York School of Art, where he studied with William Merritt Chase. A few years later, in 1908, having returned to the Northwest, he used money earned through writing to attend the Académie Julian in Paris, France. In the decades that followed, Belmore continued his love affair with the outdoors and translated his mountaineering and creative skills into writing outdoor survival and hunting guidebooks and adventure stories for boys, as well as painting.

Belmore’s art was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere. In 1926, he was awarded first place in a national competition at the Corcoran, and his winning painting, The Chief’s Canoe, was purchased by the Smithsonian. “Belmore was one of the early artists who opened the rest of the continent’s eyes to the glories of the Pacific Northwest, both through his painting as well as his vocation as an adventurer,” remarks Jim Balestrieri, director of the J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York. Bartfield has dealt with the work of both George and Belmore for many years, and in 2000, along with Thomas Nygard Gallery in Bozeman, acquired a large number of paintings from George Browne’s estate.

When George was a young boy and the Brownes lived in the Canadian Rockies, his mother wrote of her husband and son in her diary: “What Belmore wanted more than anything in the world was to get right out in the mountains and paint pictures. What George wanted more than anything was to go camping way off from everybody and just fish the little streams for trout and watch the big animals way up high, and he made up his mind that when he was big enough he wanted to paint too and hunt the Rocky Mountain big horn sheep like Ba [George’s name for his father].”

During George’s teen years, the family spent winters in the San Francisco Bay area, where he attended the California School of Fine Arts. Each summer they returned to their Alberta wilderness cabin and George continued studying with his father.

World War II saw George drafted into the Army Air Corps, where he tested survival equipment and became the first person to survive a parachute jump from 40,000 feet. Unlike previous testers’ attempts, he avoided freezing to death by delaying opening his chute and free-falling through the coldest altitudes. But art was still George’s passion, and even while in the army he tried to devote every Sunday to sketching and painting.

After the war, in 1947, he served as an expedition artist on a climb to the summit of Mount McKinley. The following year he married, and he and his wife lived for several years in the Canadian Rockies. But because his painting increasingly focused on Eastern wildfowl, in the mid-1950s he moved his family to Norfolk, Connecticut, to be closer to his subject and the market for sporting art.

In 1952, renowned wildlife artist Carl Rungius recommended to well-known sporting art dealer Ralph Terrill that he carry George’s work. Terrill, owner of Crossroads of Sport in New York City, represented Rungius and other major wildlife and sporting artists. He became George’s primary dealer and represented him until the painter’s death in 1958. In March of that year, George and a few fellow conservation-minded sportsmen met for a weekend in New York’s Adirondack region. A companion’s gun misfired, fatally wounding the artist.

During his short career as a professional artist, George devoted himself entirely to his art. He sometimes painted up to 14 hours a day, innovating techniques to improve his skills and become more efficient in order to keep up with increasing demand for his paintings of waterfowl and upland game birds. Unlike many of his contemporaries whose imagery focused more on the hunters than their game — or who painted birds, Audubon-like, devoid of natural movement and context — George took the art to another level by capturing the realistic look and feel of birds in flight.

“His paintings of ruffed grouse exploding off boughs of pine trees or waterfowl landing on water convey considerable action and life, which not many artists achieve,” Tierney says. Adds Balestrieri, “George’s body of work is extensive and extremely significant. Despite his untimely and tragic death, he is still one of the great American wildlife painters, and certainly one of the best painters of birds.”

Clearly, both Belmore and George found themselves living in a time and place that suited them; the land was still wild and big enough for adventure painters, offering abundant opportunities to engage in their twin passions for art and the outdoors. The two had the rare fortune, as well, to enjoy a father-son relationship in which they were also mentor and student, companions in hunting, fishing, exploring, drawing and painting, and close friends. As Ordeman writes: “Belmore was the master who took on an apprentice and provided the training, the encouragement and the inspiration that enabled his student to become a master in his own right.”

- Belmore and George Browne painting, circa 1950. Image courtesy of Michael M. Schreiber

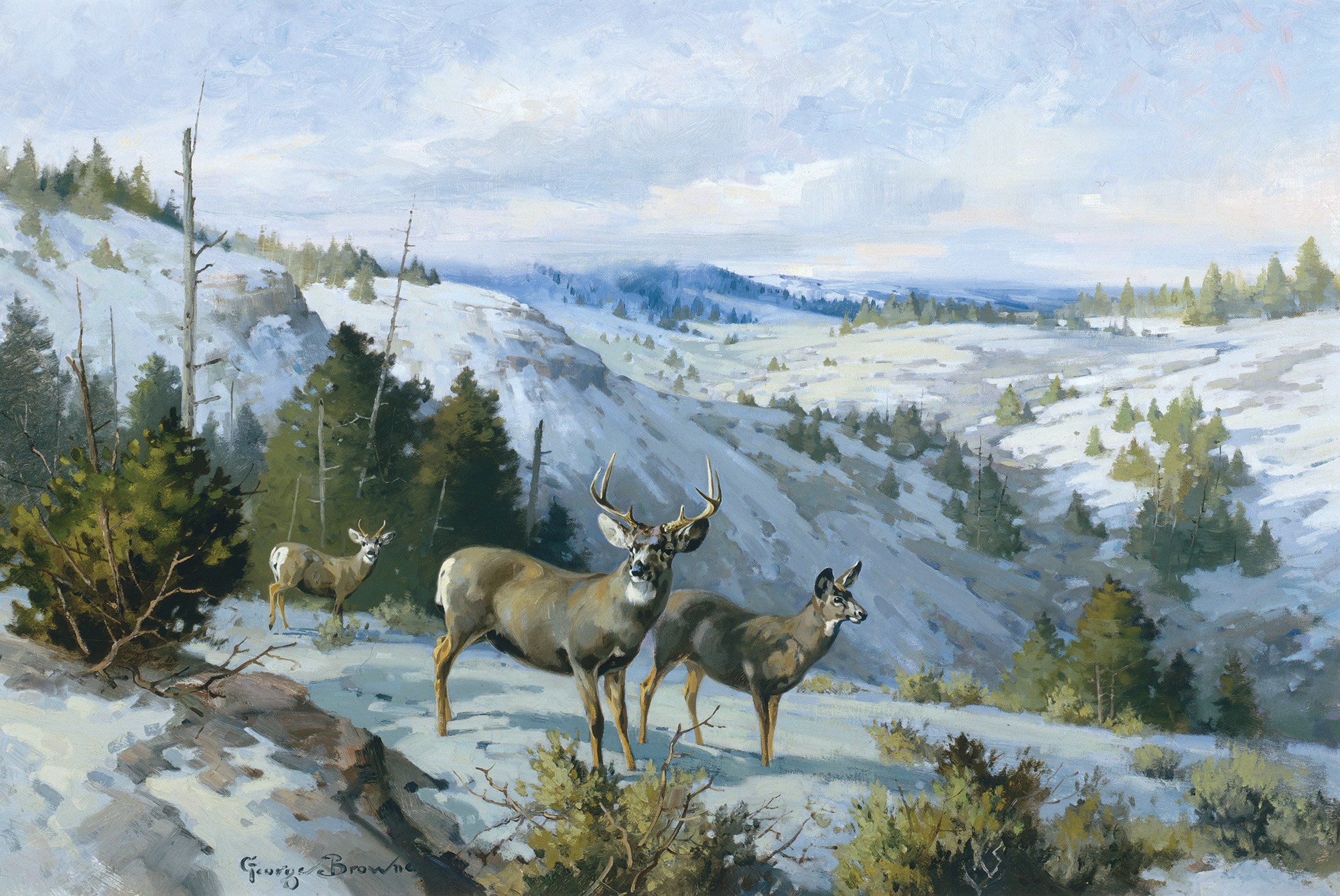

- George Browne, “Quiet Canyon” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 30 inches | 1957 Mr. and Mrs. Martin F. Wood, National Museum of Wildlife Art

- George Browne, “Pheasants Rising” | Oil on Canvas | 16 x 20 inches Courtesy of J. N. Bartfield Galleries, New York City

- George Browne, “Startled Mallards” | Oil on Canvas | 1949 Courtesy of Michael M. Schreiber

- Belmore Browne, “Sunlight and Shadow on the Great Divide” | Oil on Canvas | 25 x 30 inches | 1927 Courtesy of Tierney Fine Art

- George Browne, “Goats” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 18 inches Courtesy of J. N. Bartfield Galleries, New York City

- Belmore Browne, “White River Moonlight” | Oil on Plywood | 22 x 30 inches | 1946 JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art

- George Browne, “California Quail” | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 16 inches Courtesy of J. N. Bartfield Galleries, New York City

- George Browne, “Leaping Char (Arctic)” | Oil on Board | 20 x 16 inches Courtesy of Tierney Fine Art

No Comments