01 Feb Perspective: Bierstadt to Warhol — American Indians in the West

By 1890, two important and disparate events transpired to create a paradigm shift in the fundamental perceptions of the American West by Euro-American artists and by the country as a whole. The first event was the final battle of the American Indian Wars, known today as the Wounded Knee Massacre, in which as many as 300 men, women and children were killed on the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Wounded Knee was the culmination of the policies of territorial aggression, land acquisition and genocide that had been perpetrated upon Native populations for more than a century. The second was the U.S. Census Bureau’s announcement of the official end of the Western Frontier, meaning there were no longer large tracts of land to homestead, nor uncharted landmasses to map.

The psychological effects of these two events have been well documented. The ongoing conquest of the wilderness and commonly held beliefs in both Manifest Destiny and the indomitability of the pioneering spirit had been so woven into the collective national identity among Euro-Americans that the end of this era was met almost immediately with a sense of urgency that the West was vanishing. In response, European and American tourists, ethnographers, photographers and artists traveled west in great numbers to record descriptive accounts of the land, its Native people and their way of life before, the newcomers believed, they were lost forever.

The impact of these losses of the perceived ideals of the American West can be measured by the degree to which the Western landscape and its Native inhabitants were romanticized and idealized in literature and visual art of the time. The desire to record what was believed to be a “vanishing people” and their way of life, however, was not the only motive for such idealization. In addition, the training and philosophies of some of these artists was an important factor in their decision to move their homes and studios west.

Many of the artists who were painting in the West after 1890 were trained in European art academies with rigorous and conservative curricula. The academy standards insisted that students learn the detailed work of drawing, often for years, before they could even pick up a paintbrush. By the time they were ready to paint, they were already steeped in the central ideology of the academy believing that subject matter should focus on moral themes and the expressions of European beliefs in absolute truth and absolute beauty.

In both France and America, these ideals were thought to be found in nature, especially in the bucolic beauty of the countryside. In the United States, these values were sought in the wild landscapes and Native people of the American West, who were portrayed by many artists through overly romanticized imagery.

Late 19th-century art movements in France, Germany, England and America may be seen as a reaction to industrialization and the rise of the urban environment. Artists working within the Arts and Crafts Movement, for example, counted themselves part of the “cult of the beautiful object” in which the aesthetic beauty inherent in the craftsmanship and design of everyday objects was considered an antidote to mass production. In light of these 19th-century attempts to preserve beauty and authenticity, it is not surprising that many contemporaneous artists were drawn to the portrayal of Native people. In the faces of these people, Euro-American artists saw and admired a seeming connection to nature and the natural world and believed the lifestyle of Native people embodied European values of beauty and functionality. Additionally, exquisitely designed, utilitarian objects handmade by Native artists and craftspeople stood as counterpoints to the banalities of American commercial culture and mass production. The Taos Society of Artists is a paradigmatic example of the intersection of these multiple motivations. Along with Joseph Henry Sharp, the Society’s founder, many members — including Bert Geer Phillips, Ernest L. Blumenschein, Oscar E. Berninghaus, Eanger Irving Couse, Walter Ufer and Victor Higgins — studied in European academies. Because of their shared training, these artists were linked by a desire to paint not only from nature, as they had in Europe, but also to create traditional portraiture by paying Pueblo people to sit for them.

In the beginning, much of their work was sold to illustrate books and magazines — fueled by a desire on both coasts for ethnographic information from, and romanticized images of, the American West and the Native people who lived there. As their work became better known, it was reproduced in calendars and in advertising for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, and was exhibited in railway stations to entice tourists to travel by train to the Southwest. Finally, much of their easel work was sold to important East-and West-Coast collectors of the time.

In fact, the very motivations that drove 19th-century artists to portray the disappearing West and to explore the ideals of truth and beauty in the natural world functioned, over time, to push portraiture of Native people further and further toward polarized and stereotyped imagery. By the mid-20th century, the depiction of the American Indian had become so positioned and fixed that it could be represented by a single image of Indian-ness: the warrior on horseback with a bow, arrow and war-bonnet, and a beautiful Indian maiden at his side.

This stereotypical representation effectively melded the unique characteristics of more than 500 American Indian tribes into a ubiquitous image, one that was subsequently perpetuated by countless American and European artists, illustrators and, perhaps most egregiously and most widely seen, by filmmakers.

As America entered the 20th century, the durability and universality of the stereotyped images of Native people triggered a reaction in both Euro-American and Native artists, leading them, in varying ways, to undermine the images’ dominance. Pop artists Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol were among the first to create a rupture in the heretofore accepted and commonplace image of the American Indian. Although Roy Lichtenstein never acknowledged the sources he used to create his woodblock print American Indian Theme IV (1980), part of his American Indian Theme Series, the work appears to have been inspired by the famous photograph of Sitting Bull by Orlando Scott Goff. By reorganizing the forms, Lichtenstein negates the meaning of the visual cliché of Sitting Bull. Similarly, Warhol’s image of Sitting Bull (1986) portrays the Lakota chief as a product of mass marketing. Here, Warhol calls out the appropriation and exploitation of the image by mass media — and repeats the cycle himself.

More recently, Western artist Bill Schenck’s painting, Pocahontas (2012), offers a provocative condemnation of the merging of Native cultures and gender stereotyping found in both painting and film. His technique, using a paint-by-numbers style, draws our attention to the artificiality and flatness of representation.

It is perhaps the Native artists, however, who have found some of the most effective approaches to the deconstruction of stereotypical expectations. Influenced by the work of Francis Bacon, Fritz Scholder was one of the first Native artists who sought to reverse the stereotype of the American Indian within mainstream American culture. Using a pop art style with grotesque faces, he creates images of Native people wrapped in American flags and holding beer cans.

Likewise, Navajo artist Shonto Begay steps back from the idealized image to present more realistic contemporary depictions of Navajo people attending a funeral on the reservation in My Grandfather’s Funeral (1996), and passed out on the living room floor in Helpless (2011). He poignantly describes the “shadow looming over them” in Helpless as a “reminder to himself of a path he might have taken.”

In the painting Tea Party (1986), Kevin Red Star, a member of the Crow tribe in Montana, sheds timeworn clichés to depict a Crow couple seated at a dinner table having tea. Prominently displayed on the wall behind them is a painting of two teepees, revealing the juxtaposition of two cultures, but also, perhaps, honoring Red Star’s Crow ancestors who instead of living in government-issued cabins on the reservation, chose to occupy traditional teepees. Representational painting, especially portraiture, is never as objective as it may first appear. Image-making is the result of a complex process that merges objective aspects of the scene with the artist’s conscious and unconscious assumptions about the subject and about the purpose of art in general. These assumptions reflect both the artist’s biases and the inter-subjective community in which he or she resides.

The works of art in this exhibition represent 160 years of portraiture of American Indians in the West. Embedded in the works are deep layers of meaning that ask the viewer to not only understand the importance of the work in its historical context, but also to consider the intentions of the artist.

Both Euro-American and Native artists infuse their portraiture with subjective intent, whether acknowledged or not. These intentions pervade the portraits the artists have created, so that no portrait can be taken to be a pure or objective representation of its subject. In varying degrees, the artist’s subjective vision is inherent in the apparent reality depicted in these works of art.

- Albert Bierstadt, “The Sentinel” | Oil on Academy Board | 14 x 20 inches | c. 1860s

- Shonto Begay, “My Grandfather’s Funeral” Acrylic on Canvas | 52 x 52 inches | 2012

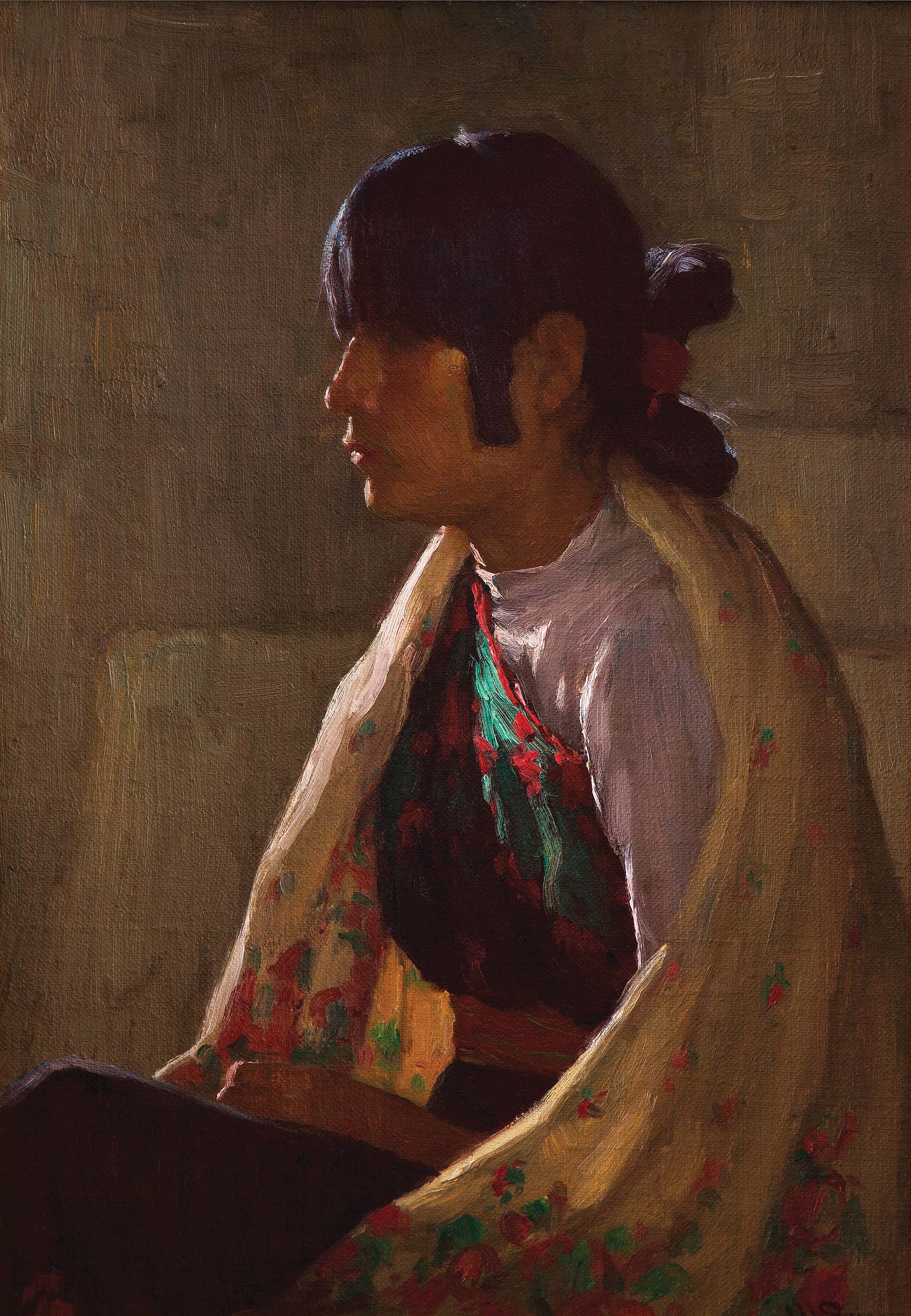

- Joseph Henry Sharp, “Crucita Taos Girl” | Oil |13 x 9.5 inches | c.1930s

- E. Martin Hennings, “Indian Horsemen” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 39 inches | c.1925

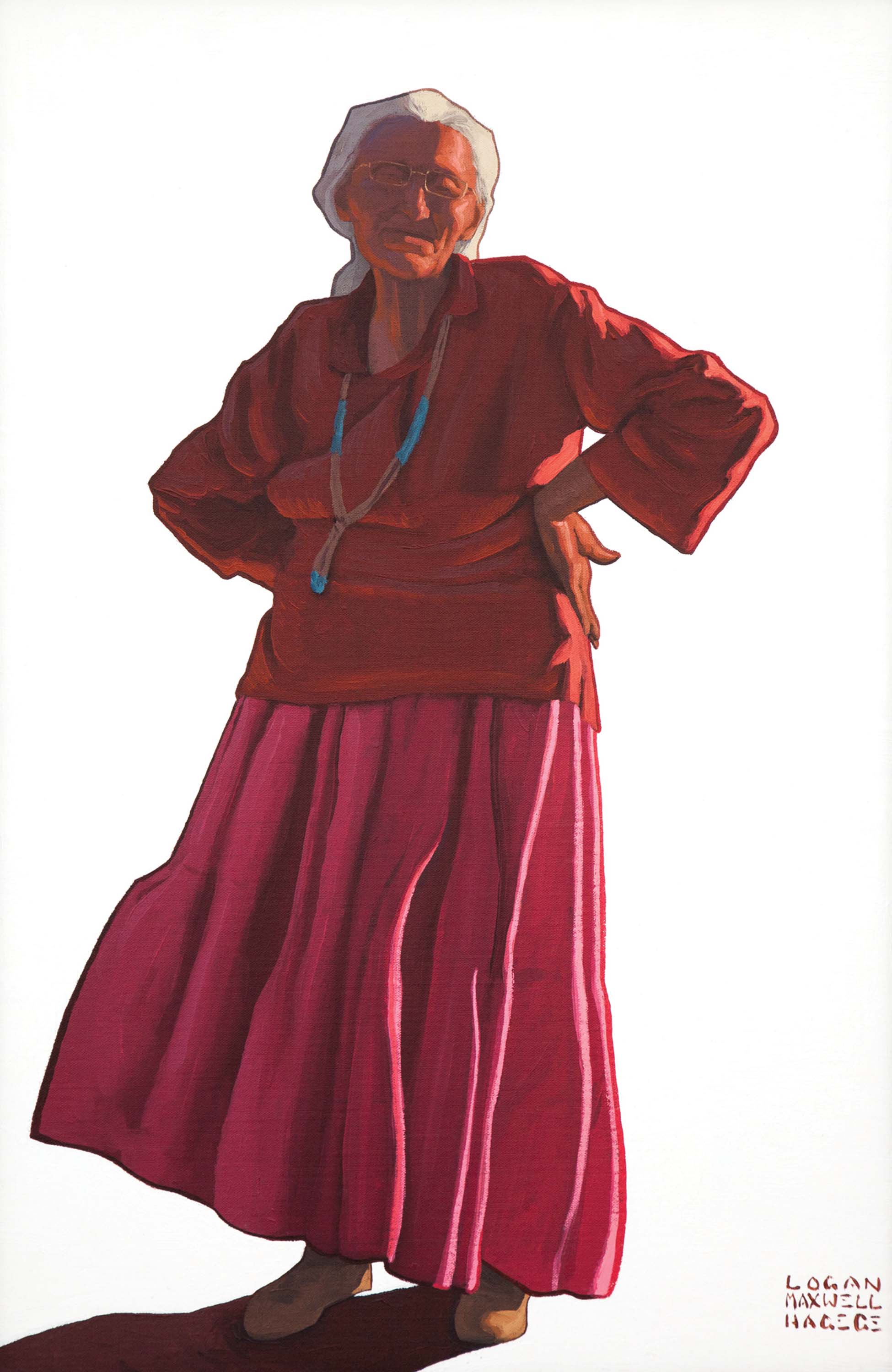

- Logan Maxwell Hagege, “Susie Yazzie” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 20 inches | 2012

- Bill Schenck, “Pocahontas Awaits” | Oil on Canvas | 45 x 42 inches | 2012

- Shonto Begay, “Helpless| Acrylic on Canvas | 44 x 58 inches | 1996

- Walter Ufer, “Greasewood and Sage” | Oil on Canvas | 25 x 25 inches | 1930s | Collection of John and Toni Bloomberg

- Kevin Red Star, “Tea Party” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches | 1986

No Comments