01 Dec Perspective: Carl Rungius [1869-1959]

Amid a career that established him as a master painter of big game animals of North America, Carl Clemens Moritz Rungius questioned the habit of distinguishing between wildlife art and art.

“What do you mean, Sporting art? There is only art; it may be good or bad, but it’s still art,” he said in Carl Rungius, Big Game Painter: Fifty Years with Brush and Rifle, the 1945 biography by artist-cum-writer William J. Schaldach.

It was not an academic point for Rungius, a German-born and classically trained artist whose love for the American West spurred him to immigrate to the United States to establish a career that began in the latter 19th century and spanned the first half of the 20th century.

“It was an important distinction to him: He wished to be regarded as an artist and not to be pigeonholed because of the subject matter he chose to depict,” said Adam Duncan Harris, curator of art at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Rungius’s insistence that the measure of artistic merit was most valid when it was independent of genre set the stage for an argument that has been quieted, but not silenced, by time. Even as Rungius’s oils of the iconic, almost mythic, wild animals of the Western United States and the Canadian Rockies fetch princely sums, the echoes of a long-standing debate sound from auction rooms to museum galleries.

“There is a good deal of snobbery remaining to this day about wildlife art,” said Harris, adding that the uninitiated may at the start be inclined to categorize a canvas bearing bighorn sheep, bull moose or pronghorn antelope as “yet another trophy on the wall.”

For Rungius, an avid sportsman whose instinct to conserve the animals he hunted and painted matched his drive to gain the approval of the art establishment, there was but one path to perfection.

In 1894, the artist, then in his mid-20s, was invited to visit an uncle in the United States, which would shortly become Rungius’s permanent home. A sojourn in the Wyoming wilderness set his course as a painter, pursuer and admirer of Western wildlife.

In a practice all but unparalleled for its place and time, Rungius trekked to the backcountry, where he immersed himself in the close study of keystone animals in their native environments.

Heir to a European tradition of Naturalism and Realism, Rungius would become father to a tradition tied to America’s nascent conservation movement spearheaded by such figures as Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir. Vested in an artistic approach that objectified animals, Rungius would unbind certain constraints imposed by his training in order to shape a legacy in the United States of stand-alone animal art that has influenced the generations.

It is the model most likely to strike a chord with the mainstream rather than appeal to an aristocratic few favoring animal images that were solely representative of the hunter-and-hunted relationship. Rungius presents the natural world, and the animals that inhabit it, as the natural world presents itself: expansive, never exclusive.

“The prevailing movement had been hunting scenes painted for royalty, for the aristocracy. The modern tradition — established more than a century ago — provides an animal a place on the landscape,” said Kathryn Robinson, fine-art specialist with Copley Fine Art Auctions in Boston.

And that place is separate from status conferred by human beings.

“What it has become is an art movement that has aligned itself with caring for and caring about the wild creatures in wild landscapes,” said the National Wildlife Art Museum’s Harris.

Underpinning the conservationist impulse, then and now, are sportsmen. Yet at the dawn of the 20th century, a social impulse was equally in play. At a time of rising industrialization, increased mechanization and widespread urbanization, the lands west of the Mississippi glittered with the promise of renewing a manly ruggedness.

“It was the onset of an era that brought concern that civilization was draining American men of their virility by confining them to a material existence,” said Amy Scott, the Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross curator of visual arts at the Autry National Center of the American West in Los Angeles. “For upper-class American men — equipped with money and leisure — wilderness landscapes presented the opportunity to reclaim their masculine identity.”

Rungius spent winters in a studio in New York painting the animals and the landscapes that drew him seasonally to the remote stretches of Wyoming and Canada. In an evolution of style influenced by Impressionism, Rungius moved from tight, detailed portraits of animals cloaked in somber tones to painterly renditions marked by broad brush strokes, bold colors and illumination of natural lighting.

David J. Wagner, author of the book American Wildlife Art, makes the case that Rungius is three artists in one: illustrator, wildlife draftsman and Impressionist painter. Wagner credits Rungius with professionalizing wildlife art in a way that succeeding artists — including the late Bob Kuhn — have acknowledged as a debt of gratitude.

“Rungius elevates the style to a new plateau,” Wagner said.

An early 20th-century painting of moose, Survival of the Fittest, in the Rungius gallery at the National Museum of Wildlife Art — which contains the largest collection of the artist’s work in the United States — exemplifies an early style that capitalized on overtly depicting the drama of the natural world.

“We see him working out how to depict moose, working with the atmosphere, with action,” said the museum’s Harris. “He evolves to tell stories that aren’t so clear cut. In later years, it is implied action.”

Paradoxically, subtlety lends power to the paintings. And the phenomenon is not lost on viewers.

“You have the sense his animals could walk right off the canvas; that is a rare talent,” said Jane Weinke, curator of collections with the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin.

In the Bighorn Country, a 1943 oil at the Rockwell Museum of Western Art in Corning, New York, depicts bighorn sheep against the backdrop of snow-swept mountains. It also illustrates the mature style of an artist whom James Peck, Rockwell’s curator of collections, said broke ground for animal painters to come.

“His career represents a crucial development for mid-to-late 20th-century wildlife artists,” he said.

Rungius’s embrace of Impressionism was not universally celebrated at the time. Patron William T. Hornaday, head of the New York Zoological Society, was instrumental in furthering commissions of illustrations by Rungius and yet took a dim view of the transformation in style.

“Hornaday complained that some of his work for the society was too impressionistic. It was along the lines of, ‘How dare you?’” said Lorain Lounsberry, senior curator of cultural history at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta. The museum houses the bulk of Rungius’s finished works, plein air sketches and the contents of his studio in New York, as well as the summer studio Rungius established in 1921 in Banff, Alberta.

Biographical sketches of Rungius fasten on the artist as much as the sportsman, on the creative instinct as much as the outdoor exploits.

In “How Carl Rungius combines art with the adventures of a sportsman,” a feature that appeared in the February 2, 1913 edition of The New York Times, Rungius grapples aloud with judgment of his work that is suspended between its scientific significance and its artistic quality.

The newspaper quotes Rungius: “For me, my pictures are simply animal pictures and I can’t help deploring the insistence with which the general public looks upon animal pictures as illustrations of natural history …”

Inquiries about paintings by Rungius are legion at Ackerman’s Fine Art, a gallery in Purchase, New York, that specializes in key American and European paintings from the 19th century on.

“He’s very sought after,” says owner Kenny Ackerman.

For Rungius, a highlight of a career that ended at the easel in 1959 was approbation of the established art world with entrée in 1920 to the National Academy of Design. Landscapes were the method to the honor, but the means was talent.

In early works, animals that took shape under Rungius’s hand are outside it. In his prime, Rungius painted from within the animal outward, from an inner nature to an outer expression, from the wilds and into legend.

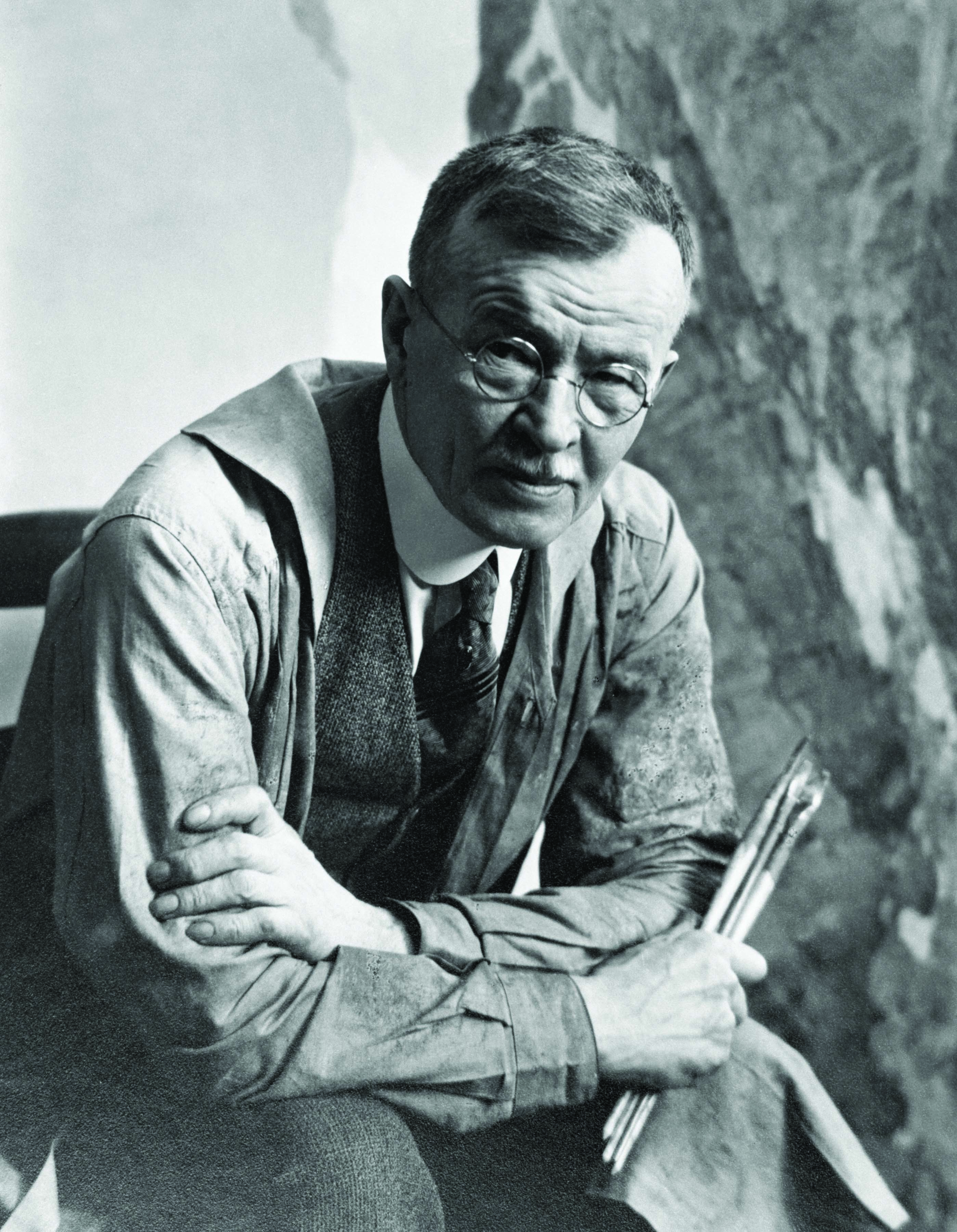

- Carl Rungius, ca. 1920-1925

- “Moose on Head of Ram River” | Oil on Canvas | 25 x 30 inches | c. 1940 | JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art | Copyright of the Artist’s Estate

- “The Cragmaster” | Oil on Canvas | 16.5 x 12.25 inches | 1912 | JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art | Copyright of the Artist’s Estate

- “The Humpback” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches | c. 1945 | JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art | Copyright of the Artist’s Estate

- “Caribou in the Mountains” | Oil on Canvas | 32 x 46 inches | c.1920 | JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art | Copyright of the Artist’s Estate

- Carl Rungius, 1910, sketching a bear, Jonas Pass, Alberta

No Comments