24 Jul Perspective: Elling William Gollings [1878-1932]

The rhythmic rocking of the steam engine brought the young man in the chair car from a deep sleep and back to reality. Bill Gollings looked out upon the rolling plains of western South Dakota as he pursued his dream of heading West. It was 1896, nearly two years before he would arrive at the Rosebud Creek of Montana where his brother had a ranch.

Elling William Gollings was born on March 17, 1878, in Pierce City, then the Territory of Idaho. When his mother was injured in a fall, the family went back to Chicago for her treatment, where she later died.

Gollings’ father remarried and the family moved to Lewiston, Idaho, in 1886. When aspirations for machinery and mining ventures did not come to fruition, the family again moved back to Chicago in 1890. While he was in school, Gollings learned perspective and showed an interest in drawing.

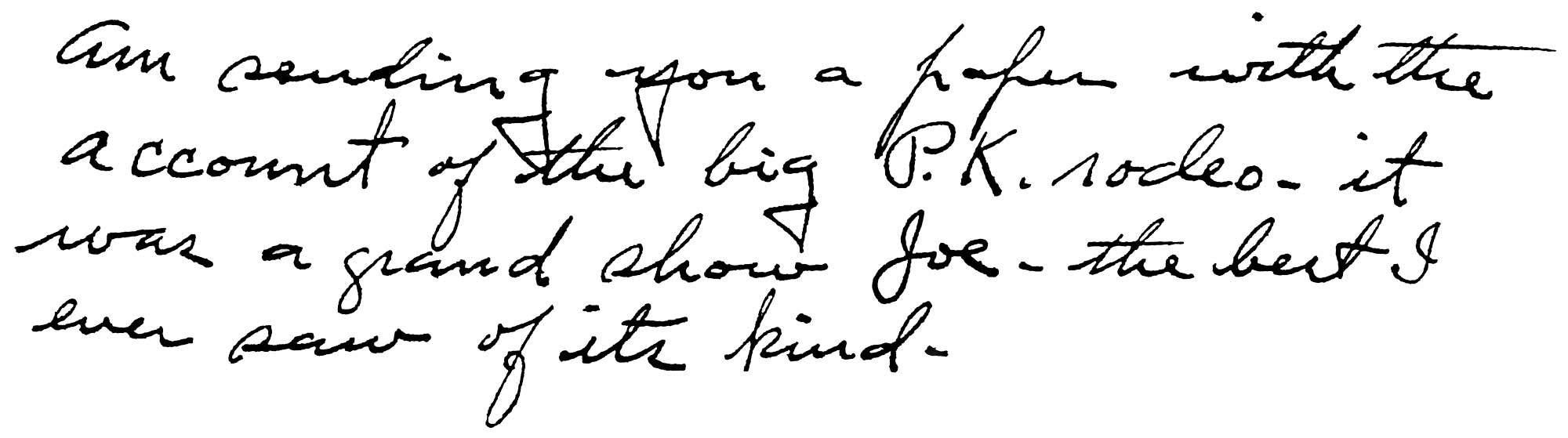

By the late 1890s, the Old West was in its waning years and Gollings wanted to be there. With his natural talent and steadfast desire, Gollings would go on to chronicle his experiences on paper and canvas for the benefit of future generations. The art of Elling William “Bill” Gollings was based not on the recollections of others but from his own experiences out West. His experiences in the field and in the saddle would render him an expert — in fact, later in life Gollings was often asked to judge rodeos because of his intimate knowledge of proper technique — and were documented both in his personal journals as well as in stacks of letters to friends, including those to fellow artist Joe De Yong.

Gollings arrived in Rapid City, South Dakota, in 1896. Along with a traveling companion, he sought work in order to raise some cash to extend his trip. In Marshland, the pair bought a couple of horses and headed north, stopping along the route to work for food and lodging. Jobs were scarce and the young men could not afford to be selective. One of their first jobs was digging potatoes, which they labored at until the snow began to fall late in the year.

The men parted ways, selling their horses to buy clothes for the winter. Gollings found work carrying mail to a post on the railroad. During the winter, he also began to produce sketches and modeled horse heads from laundry soap. In his 1923 autobiography, Gollings emphasized his desire to “punch cows,” but lamented that he did not have a horse or the necessary accoutrements. North of Belle Fourche, Gollings took a sheep-herding job. By the fall of 1897, he had the funds to pursue his dream of working for a cattle operation.

After a snowy winter herding cattle for the Turkey Track outfit in South Dakota, Gollings headed further west to Montana. He could barely contain his excitement on arriving at his brother’s ranch on the Rosebud Creek near the Yellowstone River in April, 1898. His brother, DeWitt Gollings, provided him with a fresh horse and the cowboy artist was off to explore the region.

Perhaps more often associated with Wyoming due to his eventual residency in Sheridan, Bill Gollings spent time in and had great affection for both Montana and Wyoming. One of his first jobs in Montana was with the F.U.F. horse outfit. His tenure there afforded him the opportunity to live the last years of the true Old West. The experience also gave Gollings perspective that would distinguish and define his art. In The Circle, and many of his other paintings, the F.U.F. brand can clearly be seen.

The F.U.F. was an enormous operation with physical boundaries ranging west from Rosebud Creek to the Big Horn River and north from the Yellowstone River south to the Indian reservations. The total range encompassed nearly 1,600 hundred miles and accommodated a herd of horses up to 17,000 strong.

Gollings took his work seriously and showed uncommon dedication. “There is no room for the cowardly or the unfit in a horse outfit,” he was quoted in a 1907 news article that ran in The Detroit News Tribune. “The work is different from the work of the ordinary cow puncher, for there are no lazy moments in it, save that there is no night guard to stand and the ‘horse fighter’ spends his evenings around the camp fire, or rolled in his tarpaulin beneath the stars. But the man who is good enough for a horse outfit must show that he is first of all a genuine ‘bronco buster.’ He must be able to handle all kinds of horses and handle them fearlessly.” By all accounts, Gollings was earnest in his work.

Meanwhile, when Gollings was not in the saddle, he was working to produce a body of work through much trial and plenty of error. Many of his works produced between 1900 and 1905 had problems with the muddiness of his palette range. Gollings struggled too with conflicts of composition and design.

On April 22, 1904, an article in The Sheridan Post announced the sale of three paintings by Gollings at Freeman’s Paint, Wall Paper and Art Store in Sheridan. Later that year, a man from Germany arrived in Wyoming to become a Forest Service Ranger. This man was to become a significant part of Gollings life. His name was Hans Kleiber.

In 1905, a combination of events dramatically altered Gollings’ career. The first was the opportunity to attend the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts after he won a scholarship in composition. The second was the establishment, by the acclaimed painter Joseph Henry Sharp, of his cabin at Crow Agency, Montana. Gollings was easily accepted into Sharp’s clique.

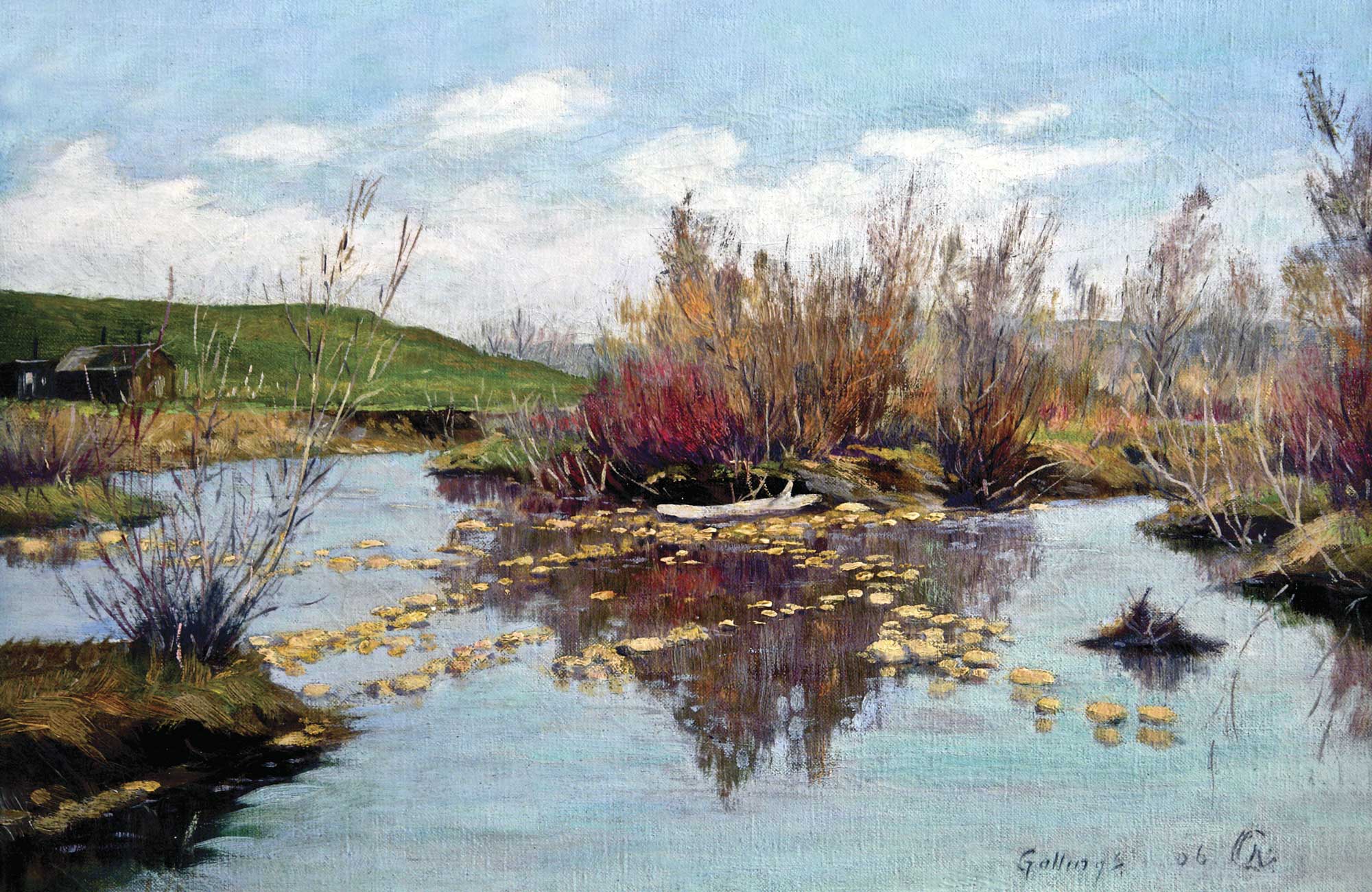

For Gollings, meeting Sharp was instrumental for his career. He was introduced to a network of notable artists, including Charles M. Russell, W. H. D. Koerner, Will James, Edward Borein, Hans Kleiber, Frank Stick and Joe De Yong, many of whom were linked together through the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. This network of artists regularly critiqued Gollings’ work and the benefits are clearly visible in his work after 1905, in such paintings as his untitled 1906 landscape.

Seeking another outlet for his work, in 1908 Gollings partnered with Rex Schnitger to form The Range Land Publishing Company. His selection of postcards appealed to guests at the dude ranches around the area. Gollings’ increasing popularity resulted in a major calendar company purchasing the reproduction rights to several of his works.

In 1917, with his art career in full gear, Gollings married Mauve Scrivner. Nine years younger than Gollings, and with a reportedly contrasting personality to the artist’s, the couple separated after just a year of marriage. It was a failure that would plague Gollings for the rest of his life.

In 1918 Gollings completed four large paintings for the Wyoming State Capital building: Indian Attack on the Overland Stage, Emigrants on the Platte, The Smoke Signal and The Wagon Box Fight. The commission signaled to Gollings a true acceptance by the residents of Wyoming, and an appreciation for his talent.

Gollings became known as early as 1913 for what he termed “pot boilers” — small paintings of usually 10 inches by 7 inches. The price range of his “pot boilers” assured quicker sales and enabled Gollings to live off his art. Though he was prolific in producing the diminutive works, which were often used to develop ideas for later pieces, Gollings longed to paint larger works.

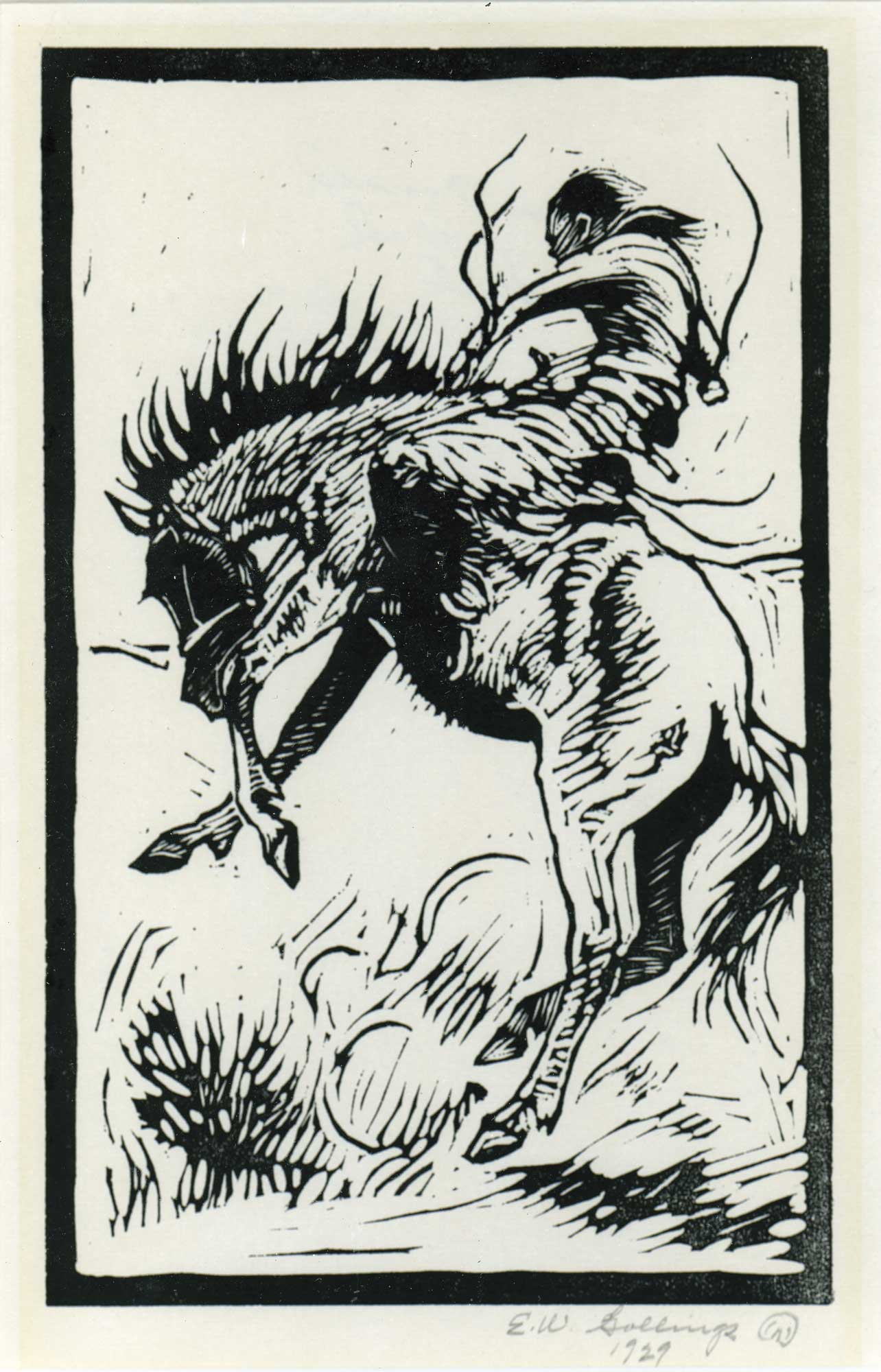

Hans Kleiber’s help was pivotal for Gollings, as he expanded his art career into printmaking. From the onset, Gollings could produce fine-art prints, easily displaying his keen use of draftsmanship.

One of the true cowboy artists of his time, Bill Gollings lived through the fading days of the Old West. Few artists knew the subject as well as he. Recently a painting by Frederic Remington, for example, was reproduced for the cover of a major museum magazine. In the painting, Buying Polo Ponies, a riderless horse is depicted with a bridle bit in its mouth. Upon close inspection, the bit of the bridle is clearly portrayed in the position that would only be natural when a rider is pulling back on the bridle reins. Gollings would not have made such an error, for he knew horses, tack and the true workings of this era.

Perhaps most often recognized for his 1931 Sheridan-Wyo-Rodeo poster design, Gollings’ range and diversity as an artist are often overlooked. In reality, Gollings was adept in pen and ink, graphite, watercolor, etching and oil. Several fine works are on display at the Sheridan County Fulmer Public Library, many of which were purchased annually from the artist by the high school graduating senior classes. Bill Gollings was the real thing: an authentic cowboy and a true artist. It was the natural blending of those two things that solidified his legacy.

Gollings died shortly after suffering a heart attack in April, 1932. He was 54.

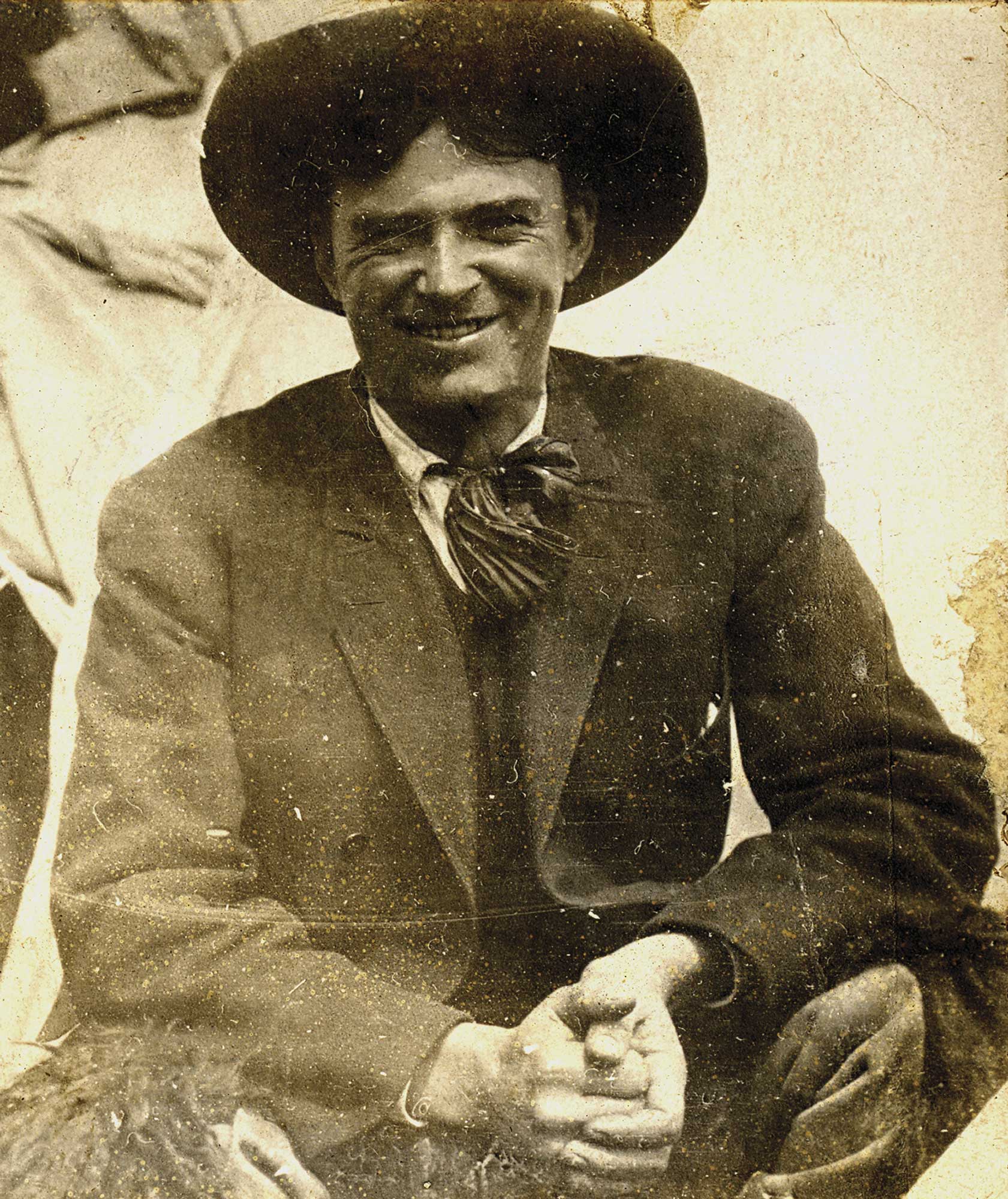

- 1906-07 Gollings from postcard with cancellation date removed

- The Roper | 1924 | Oil | 20 x 16 inches

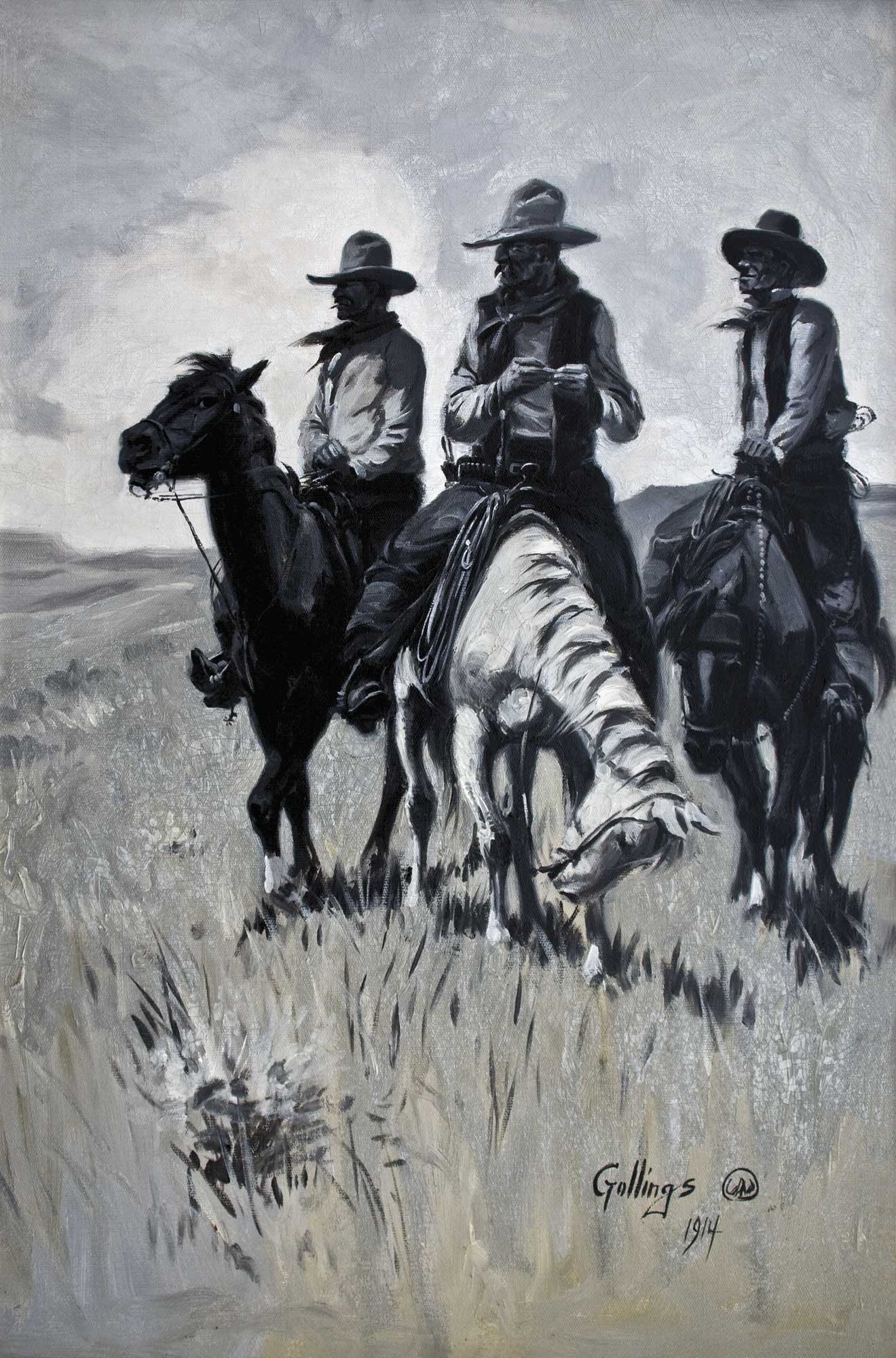

- Range Riders | 1904 | Oil Grisaille | 30 x 20 inches

- Bucking Horse | 1917 | Oil | 11 x 7.5 inches

- Untitled Landscape | 1906 | Oil |12 x 18 inches

- Indian Attack On The Overland Stage | 1918 | Oil | 36 x 60 inches

- Sheridan Rodeo Poster | 1931 | Master Proof including border

- Untitled | 1929 | Bucking Horse Linoleum Cut | 11 1/8 x 8 3/4 inches

No Comments