19 Oct Perspective: Frederic Remington

Out of the darkness comes danger — the fear — as a patrol is fired upon. Its enemy is unseen, the gunshots unheard by the viewer as horses rear and riders flinch, drawing pistols and stiffening against saddles as bullets pock the river’s surface or explode on rocks before it. A horse, ashen with moon-light, seems paralyzed as it leans back, away from its assailants, away from danger and into the fear.

Fired On, at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, is one of Frederic Remington’s celebrated nocturnes — brooding meditations on darkness and light. It was the most commented upon piece in his 1907 Manhattan show, the second of three fine-arts exhibits that introduced the new Remington: one who had turned his back on magazine illustration and made every effort to become a respected painter. Critics were generous in their praise and in the lyricism of their descriptions: “In such a low tone that it is almost monochrome in black and white,” the Brooklyn Eagle wrote, “a white horse in the foreground shows the only big light … and in the gloom beyond the other horses are plunging about in terror.” While extraordinary, Fired On is representative of the 70-odd night scenes Remington concentrated upon in the last years of his life. “In these he has made a great stride forward,” the New York Daily Tribune wrote. “Study of the moonlight appears to have reacted upon the very grain of his art … Fired On [is] one of the most truly dramatic compositions he has ever put to his credit … it would be difficult to congratulate Mr. Remington too warmly.” These and other reviews delighted Remington. In his diary he wrote that his show was “a triumph … I have landed among the painters and well up too.”

If Fired On’s subject is fear, or knee-jerk panic, it’s one familiar to connoisseurs of Remington’s late work. “Filled with uncertainty and threatened violence,” the National Gallery’s Nancy Anderson has written, “they reflect Remington’s personal disquiet as well as that of a newly modern world.” Abstract art was de rigeur, and there may have been fear in tackling fine art. But there certainly was fear unleashed in the nocturnes from his childhood and his months in Cuba covering the Spanish-American War. Remington’s father had been a Civil War hero, and as Peggy and Harold Samuels write in Frederic Remington: A Biography, the colonel “had not believed in Remington’s early talent.” And, “Remington felt that he had not been a dutiful son to this normally gentle but martially fierce man … ” The solution was combat. When Theodore Roosevelt gathered his Rough Riders for that “splendid little war” of 1898, Remington was keen to experience “the greatest thing which men are called on to do.” Since he knew Roosevelt from illustrating his writings, and from their shared experiences out West, he accompanied him on the adventure Remington hoped would make him “a heroic war correspondent” for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. The suffering and random carnage he found in combat sickened him. “I didn’t get over Santiago for a year,” he wrote. Added to its terrors had been the unpredictability of jungle warfare, its guerrilla fighters as the unseen enemy and projecting an “unknown” that haunted him the remainder of his days.

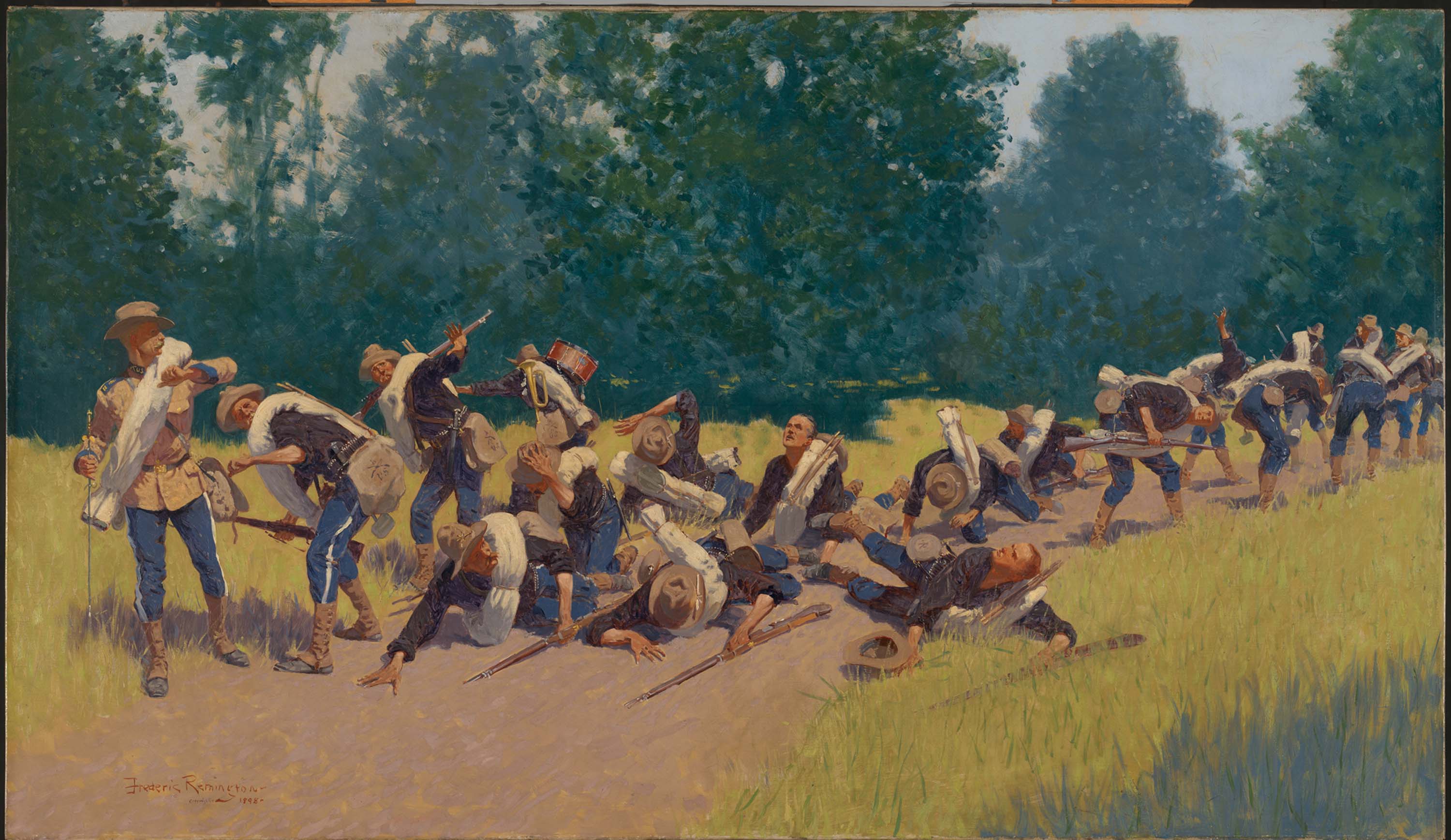

That fear was captured vividly in 1898’s painting, The Scream of Shrapnel at San Juan Hill: Troopers fall helter skelter looking in contrary directions for the source of the danger. It is a tableau of confusion and panic. Anderson notes that “He had wanted, he wrote, ‘the roar of battle.’ Instead, he found the unnerving ‘scream of shrapnel’ coming from an unknown direction …” And screams of the wounded.

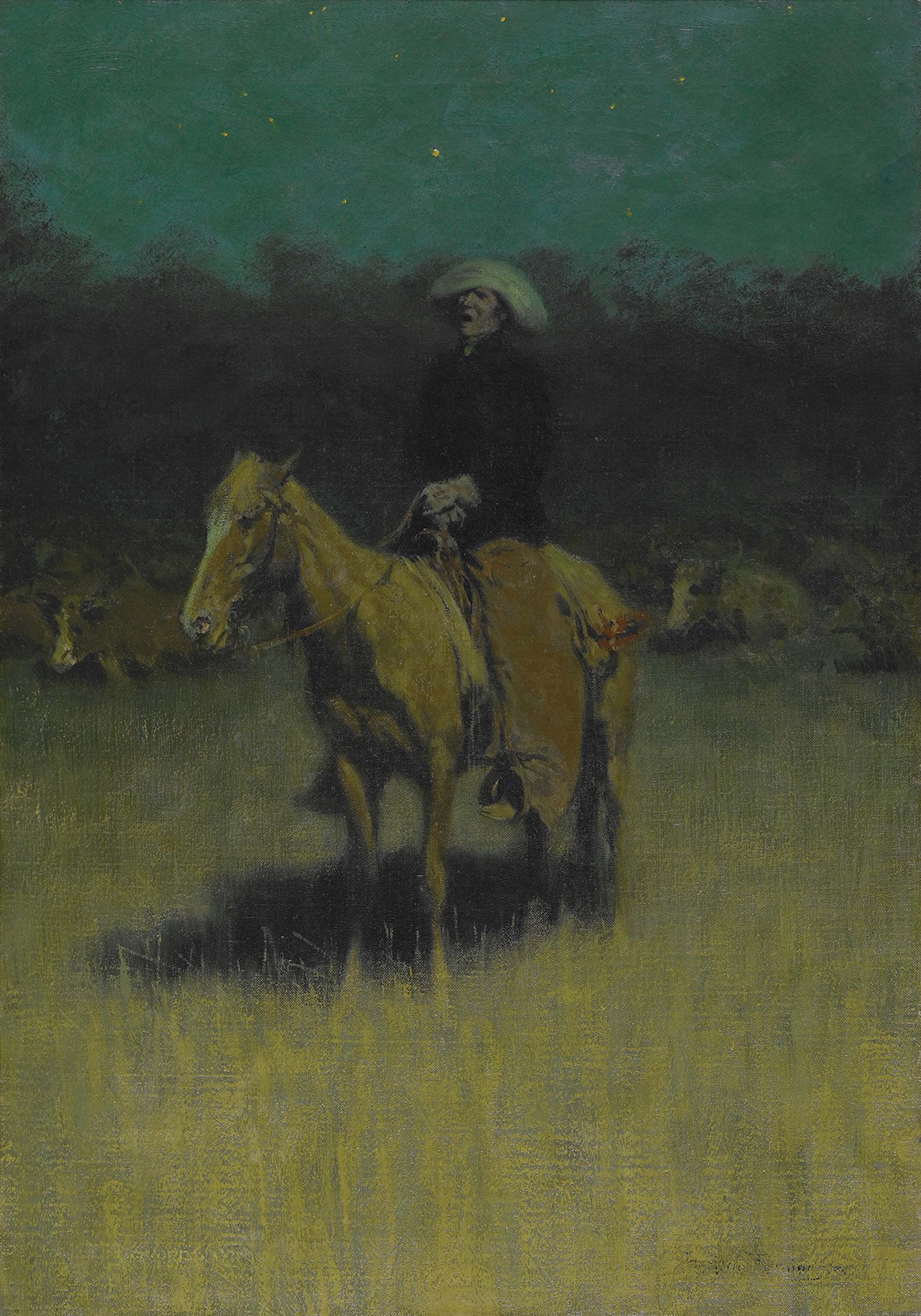

His nocturnes were an attempt to join the ranks of American painters such as Homer, Ryder and Hassam. But while their nocturnes were peaceful or, at their darkest, contemplative, Remington’s were startling — meant to startle, as their subjects had been startled. In A Taint on the Wind, a lantern-lit stagecoach hurtles down a silvery road as its horses flare from the presence of an unseen danger. In Shotgun Hospitality, a cowboy, seated against his wagon with a shotgun across his lap, rubs his chin as three robed Indians emerge from the darkness, their intentions unclear. In Moonlight, Wolf, the solitary predator stands as if himself surprised, eyes shining yellow in reflection of the stars in a field of gray-green and black, or as if considering the viewer as prey. Anderson notes, “Remington’s wolf is a killer. The eyes that engage the viewer are those of death.”

Remington was not healthy — he was gluttonously alcoholic — and death may have preoccupied him. It may have done so since boyhood. He was an only child whose father had been at war the first years of his life, and who wished West Point and a military career for his son. Instead, Remington attended Yale art school, playing football for the team, but dropped out in 1879, at age 18, to nurse his tuberculous father — who died at 46.

“The loss was greater,” Peggy and Harold Samuels write, “because it was before Remington had developed a separate life.” He had sketched soldiers and cowboys from an early age, and in 1881, inheritance in hand, he visited Montana, admiring the unfenced prairies, hunting grizzlies, apprising the last of the cavalry-Indian conflagrations and sketching. He sold his first illustration to Harper’s and after stints in Kansas as a sheep rancher, hardware merchant and saloon keeper, returned to New York to study at the Art Students League and launch his career as an illustrator.

Cuba would change that. Following his return home from war in 1898, and having produced his sketches of the bloodshed in Cuba for Hearst, Remington took a recuperative vacation to Montana and Wyoming. Despite a realization that the West he’d known as a boy had vanished, the trip inspired him. He revisited cowboys and Indians as subjects, but sketched them in nocturnes, experimenting with starfire and moonlight, in a manner that was startlingly innovational. By 1908, in a backyard fire, the artist would burn the sketches he considered illustrations, the work of “a black and white man,” having turned his full attention to the examination of color and light.

Remington had seen an exhibit by Charles Rollo Peters during the fall of 1899, which contained 16 views of California missions by moonlight. These paintings were in the contemporary mode — that of Whistler, George Bellows and the photographer Alfred Stieglitz — work that celebrated an illuminated darkness, particularly that of cities, which had recently become electrified. Remington’s reexamination of the West — its frontier days passed — incorporated the startled responses of flash photography into plein air scenes, using instead firestar and moonlight. Illumination in combat represented danger, as it had in the Old West. One ventured into moonlight or built a fire at one’s peril. Something was “out there,” in critic William C. Sharpe’s phrase, and if it saw you, it could get you.

It also lurked inside. Sharpe writes, “For what’s ‘out there’ is in here — the modern artist looking into himself.” Such self-reflection was au courant. Remington’s nocturnes were envisioned, Sharpe adds, “at the time when Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness (1899) and Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) began their own explorations of inner darkness.” Remington moved closer to a metaphorical and painterly Impressionism.

Mortality haunted him. At 48, he was ill with gastric distress and at 300 pounds, grossly overweight. Surgery in December of 1909 for a burst appendix was complicated by his obesity. He died of peritonitis a short time later. Premonitions had been rife in his work. As an observer wrote of his last New York show, “in all of Remington pictures the shadow of death seems not far away.”

Nowhere is it better portrayed than in the previous year’s Fired On. Approach it in Washington’s Museum of American Art. Horses flare and rear at an unseen danger; men flinch and draw weapons and one almost can hear their cries. The same holds true for A Taint on the Wind, at the Sid Richardson Collection in Forth Worth, Texas. Remington’s hurtling coach is as imperiled by its own force of energy as by its invisible assailant. Both seem impossible to stop.

Remington had been happy that Fired On was purchased in 1908 for $1,000, then donated to the National Museum. At that point it represented the finest of his nocturnes. Money did not preoccupy Remington — he was wealthy from his sales of paintings, illustrations and sculptures — but one can imagine what he might have thought in 2012 when Sotheby’s sold A Halt in the Wilderness, an earlier nocturne, for $2,770,500, the 10th-highest auction price for a Remington, including sculpture.

Several shows this year will or have featured Remington’s nocturnes. Treasures from the Frederic Remington Museum will be exhibited at the Museum of the Big Bend in Texas, from September 21 through December 8. The National Gallery of Art will mount The Western Frontier from March 28 to August 24, 2014. The Sid Richardson Museum has permanently displayed five Remington nocturnes in a single room. And a comprehensive catalogue of Remington’s work by Peter Hassrick, formerly of the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody, will be published by the University of Oklahoma Press in spring 2014.

Meanwhile, Fired On hangs on a far wall of the American Art Museum’s second floor, darkly sentient and stealthy, as if to bushwhack the unwary viewer.

- “The Scream of Shrapnel at San Juan Hill” | Oil on Canvas | 35.25 x 60.75 inches | 1898 Yale

- “The Bell Mare” | Oil on Canvas | 34 x 26.25 inches | Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK

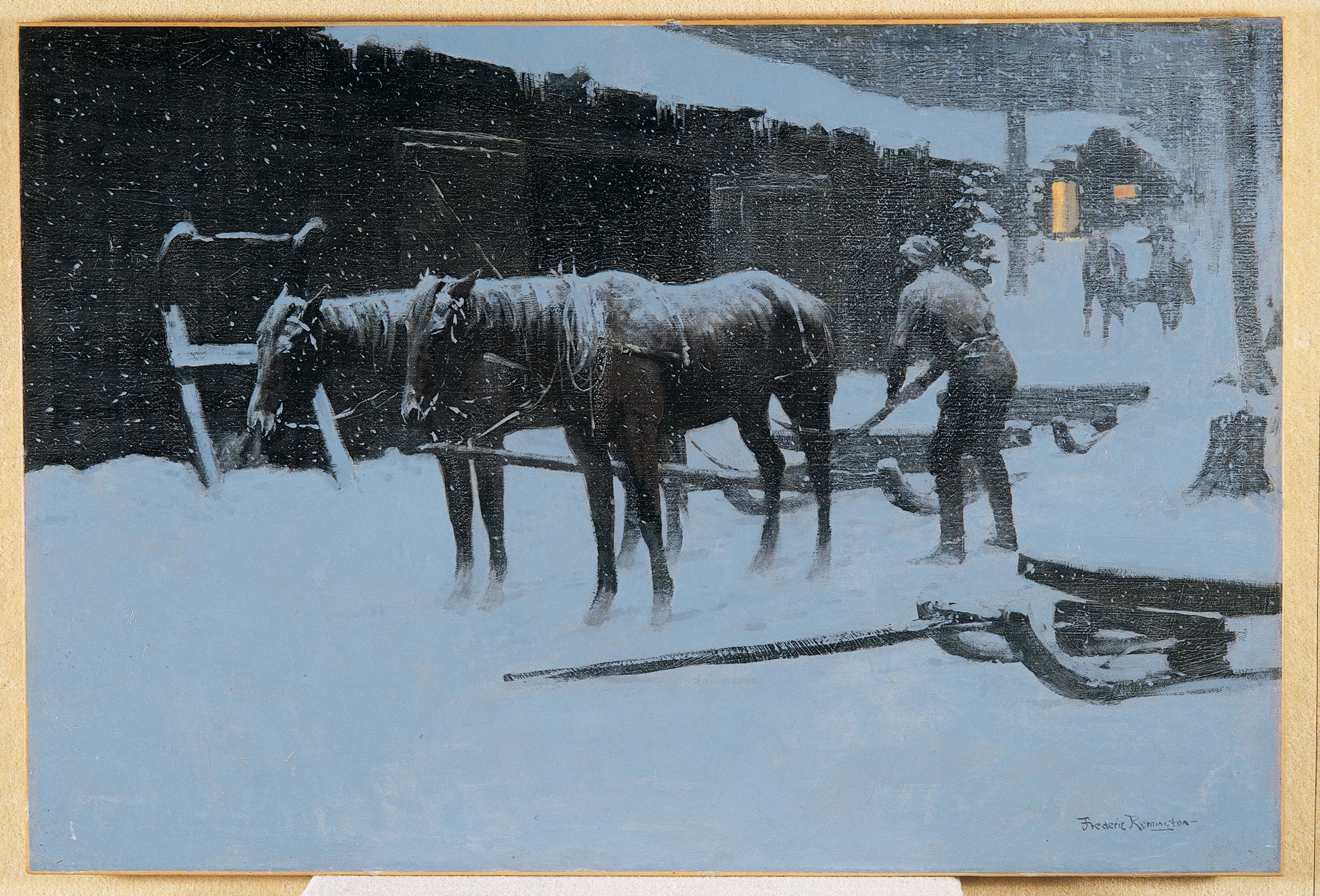

- “The End of the Day” | Oil on Canvas | 26.5 x 40 inches

- “Shotgun Hospitality” | Oil on Canvas | 27 x 40 inches | 1908

- Frederic Remington [1861–1909], “Cowpunchers Lullaby” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 21 inches

No Comments