04 Aug Perspective: Fritz Scholder [1937-2005]

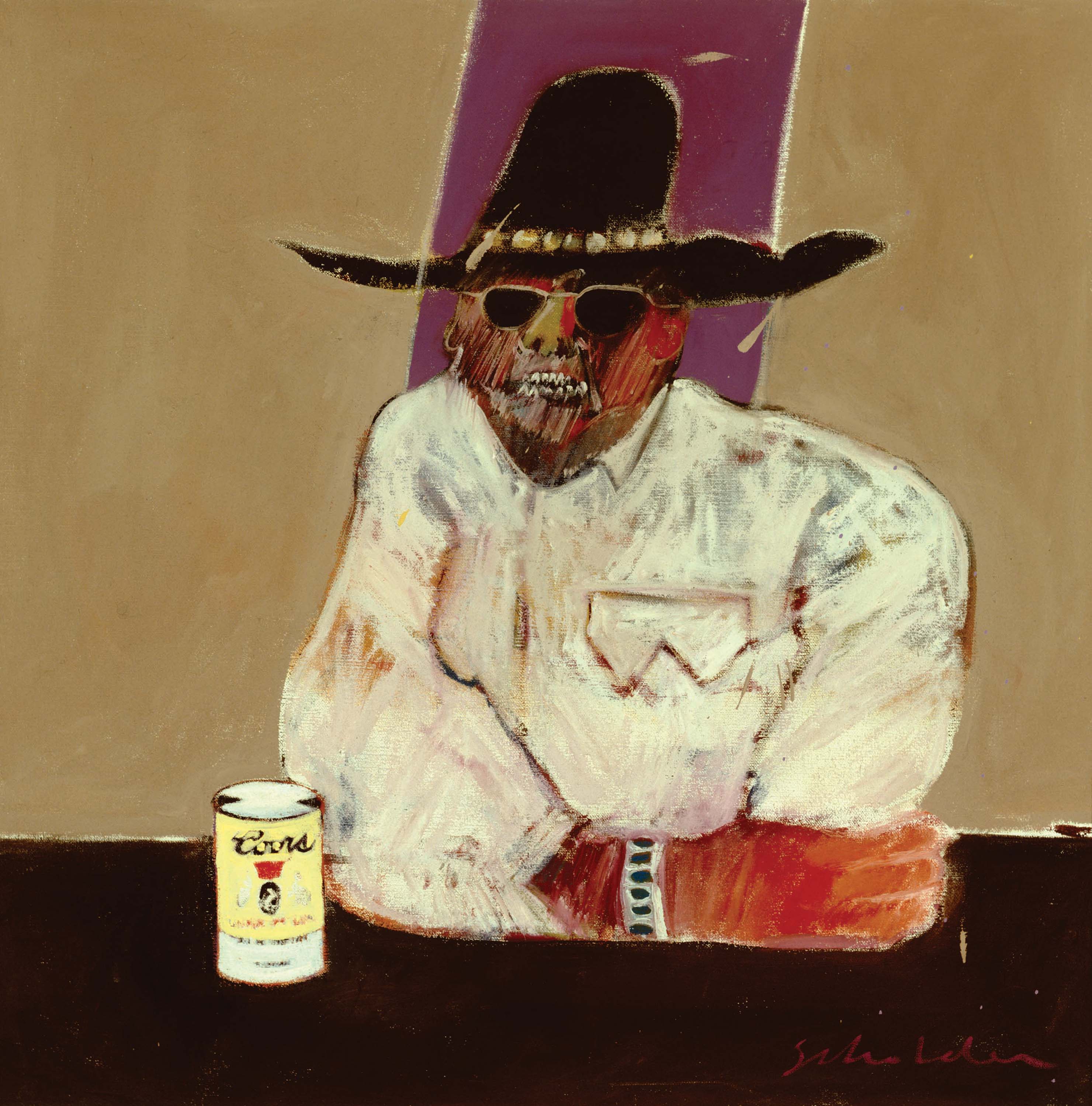

In 1969, Fritz Scholder completed the modest canvas Indian with Beer Can — and Native American art was never the same. In fact, back then there was no such thing as Native American fine art. Classic Navajo chief’s blankets and Mimbres pictorial pots were relegated to dusty displays in anthropology museums. Even Maria Martinez’s wonderful black-on-black ceramics were condescendingly written off as high-end crafts. Indian with Beer Can changed everything.

Today, the question lingers in the air like an unfinished argument: How did an artist, who often denied his Indian background, blossom into a painter who came to define that very category of art? All Scholder ever wanted was to be appreciated as an artist, rather than an Indian artist. Perversely, he discovered he could only make a living if he was perceived as a Native American who painted Indian imagery. It would remain a lifelong source of frustration.

Fritz Scholder was born in 1937 in Breckenridge, Minnesota. His father was an administrator in the local Indian school and was employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As Scholder recalled, his parents acted as if they were ashamed of their heritage. When his mother and father were married, they received wedding gifts that included Navajo rugs and woven baskets. Yet, they refused to display them in their home, preferring not to think of themselves as Indians. It wouldn’t take much of an imagination to recognize how this was the source of Scholder’s unresolved issues over his background.

Fortunately, his family valued education, with Scholder attending both the University of Kansas and Wisconsin State College. By 1957, he had moved to Sacramento, where his art studies kicked into high gear under the tutelage of Wayne Thiebaud at Sacramento City College. A year later, he was given his first one-person show by the school, and never looked back.

The real enigma was how such a conflicted personality made such great art. While Scholder’s 1998 retrospective at the National Museum of the American Indian, aptly titled Indian/Not Indian, gave the public a provocative overview of his work (and a valuable catalog), it did little to answer the question. If you agree with Francis Bacon, who said an artist’s job is to “deepen the mystery,” then Fritz Scholder would qualify as a bona fide CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

What’s interesting is that Bacon was arguably Scholder’s greatest influence. Early in his career, he traveled to London to see the painter’s work at the Tate Gallery. Scholder walked away mesmerized. But in a pattern that would help shape his career, Scholder “lifted” Bacon’s distinctive format. Dating back to his teaching years at the Institute of American Indian Arts (1964 – 1969), Scholder was accused on more than one occasion of stealing ideas from his students. Defenders of the artist say while that may very well have been true, his students didn’t have their teacher’s talent, drive or connections to succeed with the concepts he appropriated. It’s worth thinking about. After all, no less an authority than Picasso is believed to have once said something to the effect of: “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

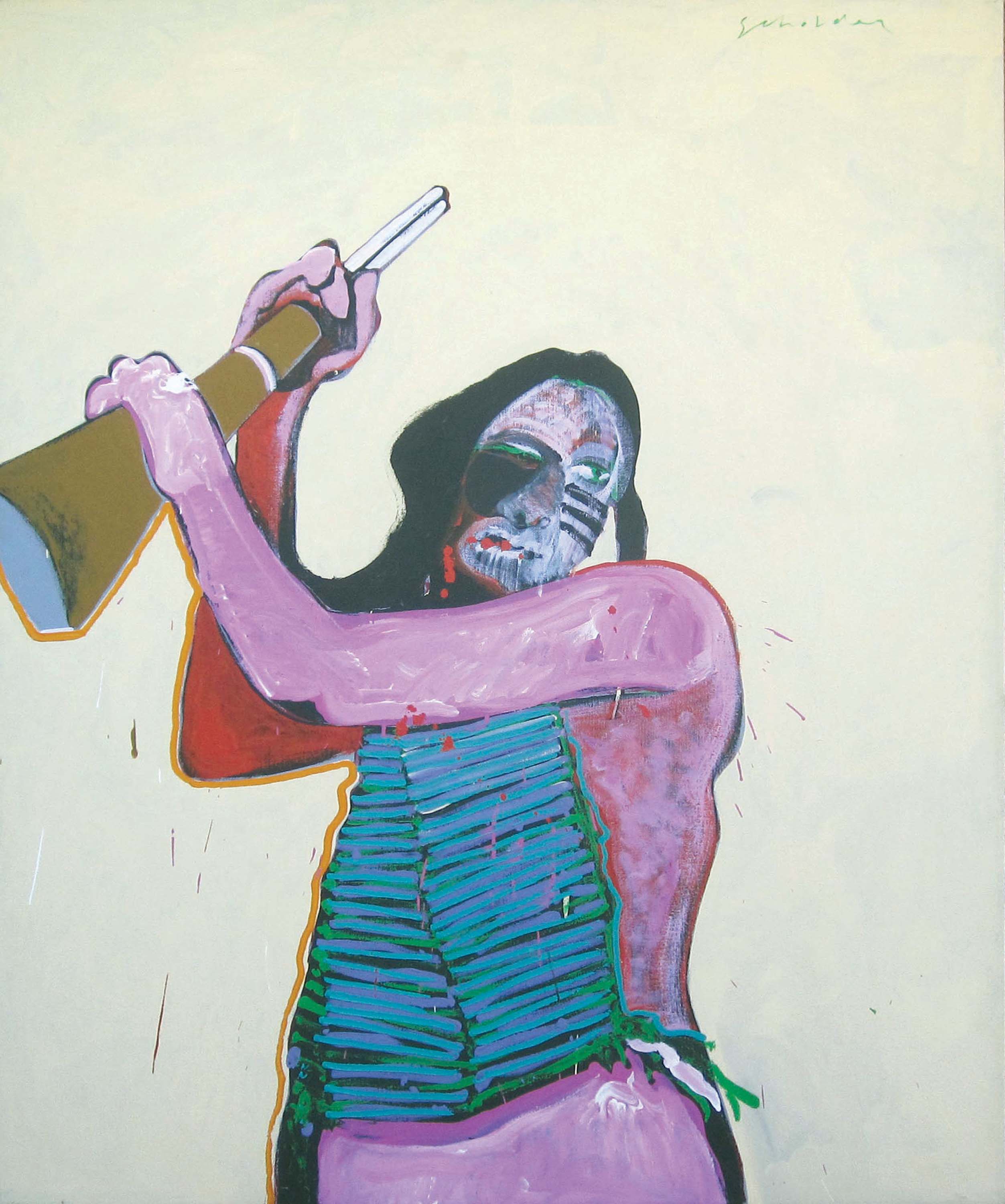

Scholder was able to parlay what he learned from Bacon and Thiebaud into a language that took static images of Indians and transformed them into figures loaded with feeling and emotion. Polly Larsen, co-owner of Larsen Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, America’s largest dealer of Scholder paintings on the secondary market, explained, “Scholder wanted to paint the Indian ‘real,’ instead of the romanticized versions by George Catlin and Karl Bodmer.” He managed to do so by placing his Native American subjects in ironic scenarios. He portrayed them as stereotypical Indians, in dress and ritual, who ate ice cream cones and draped themselves in the American flag. They even wore Western shirts, Stetson hats and hung out at cowboy bars — just like the figure depicted in Indian with Beer Can.

In a way, this painting is a Rosetta Stone that can be used to partially demystify Scholder. It’s worth pointing out that the picture was purchased by Ralph Lauren. If there’s a single name in American culture that's synonymous with the good life, it’s Ralph Lauren. Born Ralph Lifshitz to Jewish immigrant parents from Belarus, Lauren observed that most Americans came from mixed lineages, but often aspired to the so-called WASP lifestyle. Capitalizing on that realization, Ralph Lauren created a fashion empire, much in the way that Scholder reinvented himself in an attempt to live the good life defined by Lauren.

There’s a famous black-and-white photograph of Scholder — posed formally in front of his Rolls Royce convertible, holding the leash to a magnificent Afghan hound and with a towering saguaro in the background — that was a metaphor for the artist’s monumental success. It was as if Scholder needed to remind himself how far he had come in the world.

Setting the stage for his meteoric success, in 1974 Scholder joined Scottsdale’s Elaine Horwitch Gallery. It was the fortuitous meeting of two forces of nature. Horwitch, who was a character in her own right (she collected and rode motorcycles), sensed something in the air when she invited Scholder to join her gallery. In a period that spanned the late 1970s through the early 1980s, wealthy Americans began to fall in love with the Southwest, partly through the efforts of Lauren and W magazine, who helped define the so-called “Santa Fe Style.” They bought second homes in Scottsdale, Santa Fe and Jackson Hole. They decorated their vacation residences with Molesworth furniture and paintings with Western themes. By acquiring a Scholder, collectors could have it both ways: They could show they were politically correct — this was the tail-end of the radical AIM (American Indian Movement) — while decorating their homes with iconography that defined the region. Even better, they latched on to what appeared to be a good investment.

According to Julie Sasse, who once worked for Elaine Horwitch and is currently the Chief Curator and Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Tucson Museum of Art, “Fritz Scholder was definitely a superhero in Scottsdale — when he showed up in his Rolls on Marshall Way everyone stood up and took notice. Scholder caught on because he was not making saccharine images. He had an original palette, and he possessed a unique vision. It was as if Francis Bacon met Abstract Expressionism.”

But that era cruelly ended when the fad for Southwestern art faded in the mid-1980s. The Scottsdale scene contracted and Scholder left the Horwitch gallery. Sasse recalled, “He left Elaine because she could no longer meet his escalating demands. He kept raising his prices and insisted on a monthly guarantee, while also expecting a catalog and posters for each show. But what he really wanted was to go off and paint whatever he felt like painting.” Scholder visited Egypt and began a series of pictures depicting sarcophagi, augmented with bronze casts of obelisks. They never really caught on. Sasse added, “He thought his audience would follow him.”

To his credit, Scholder continued to redefine his art on his own terms. He began to look more closely at Nathan Oliveira, the esteemed Bay Area figurative artist. He incorporated Oliveira’s looser brushwork, mimicked his elongated figures, and absorbed his slightly acidic color. It was as if Scholder had been emancipated. His imagery drifted away from Indians and began to look more like contemporary art destined for SoHo. Scholder’s work now explored the more existential issues of painting. He became concerned with painting as an extension of the human spirit.

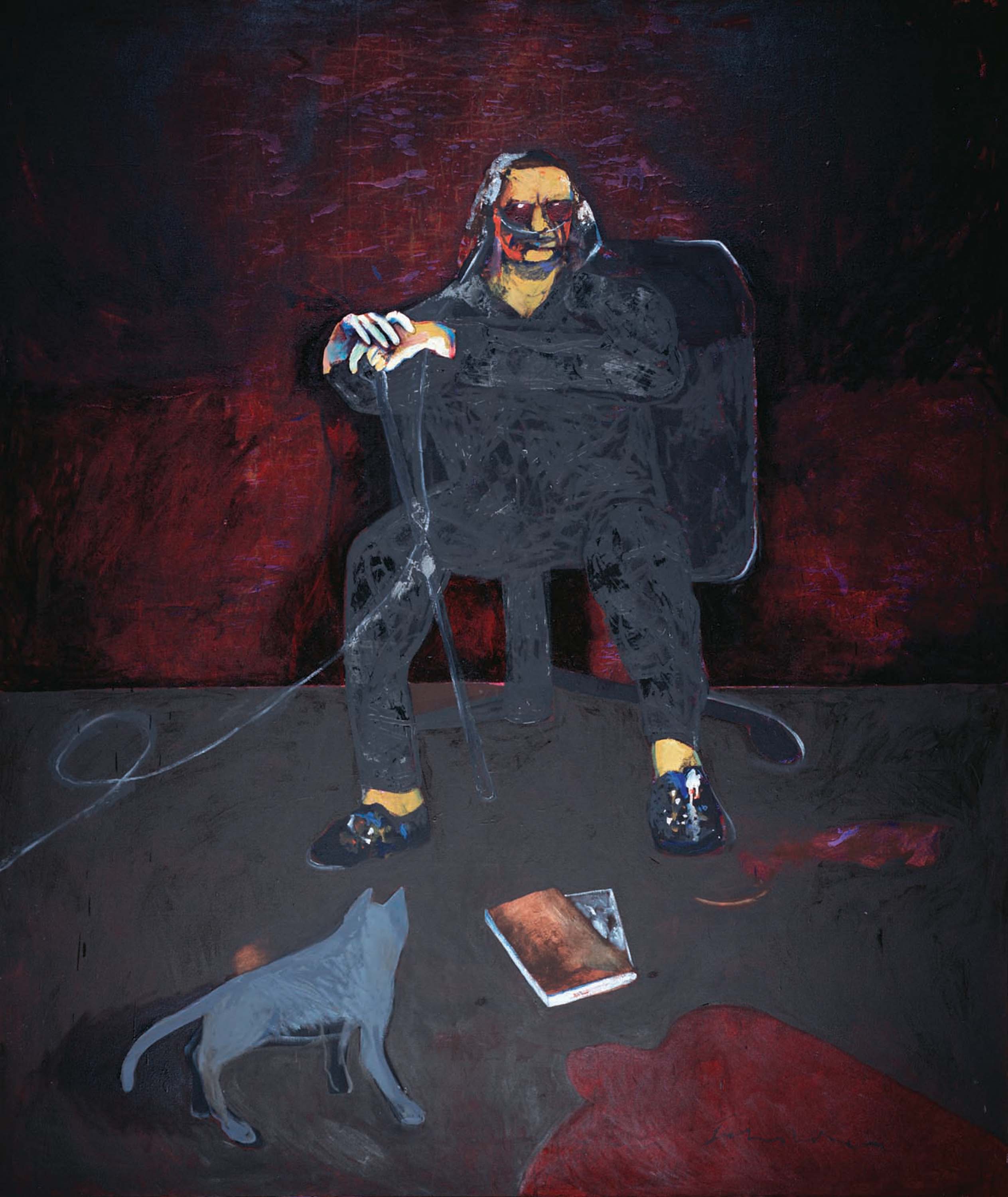

During the mid-1990s, Scholder embarked on a series of portraits — with titles like Heaven, Hell and Purgatory — that reflected his preoccupation with a life that was winding down. There’s a telling self-portrait of the artist in his old age, seated in his studio, wearing sunglasses and tethered to an oxygen tank, called Self-Portrait with Grey Cat. Painted two years before his death in 2005, he seemed to be asking himself, “Is this what my life’s come to?”

Yet Scholder had much to be proud of. After all, how many artists come to define an entire genre of art? His legacy is assured; a scan of the artist’s biography reveals the inclusion of his work in more than 100 public collections. Equally important, Scholder gave future Native American painters permission to comment on what it’s like to be an indigenous person trying to retain his traditional roots in a modern world.

The Cochiti artist Diego Romero, whose work is equally chock full of irony, had this to say about Scholder: “We all have to acknowledge his place as an artist who paved the way. Just as Maria Martinez was the matriarch of Indian ceramic artists, Fritz Scholder was the patriarch of Indian painters.”

At the end of the day, an artist is judged on his aesthetic high-water mark. Fritz Scholder left a considerable footprint on art history, filled with a stream of exhibitions, accolades and honors.

On a personal level, he had a remarkable lifestyle. His world was the proverbial movable feast with homes (at various times) in New York, Taos and Santa Fe. Scholder also assembled a substantial art collection that included several portraits of himself that he commissioned from Andy Warhol. Whether he won his lifelong struggle to be seen as a pure artist is debatable. But one thing is certain, if the title of Calvin Tomkins’ Living Well is the Best Revenge is to be believed, then Fritz Scholder got his revenge in spades.

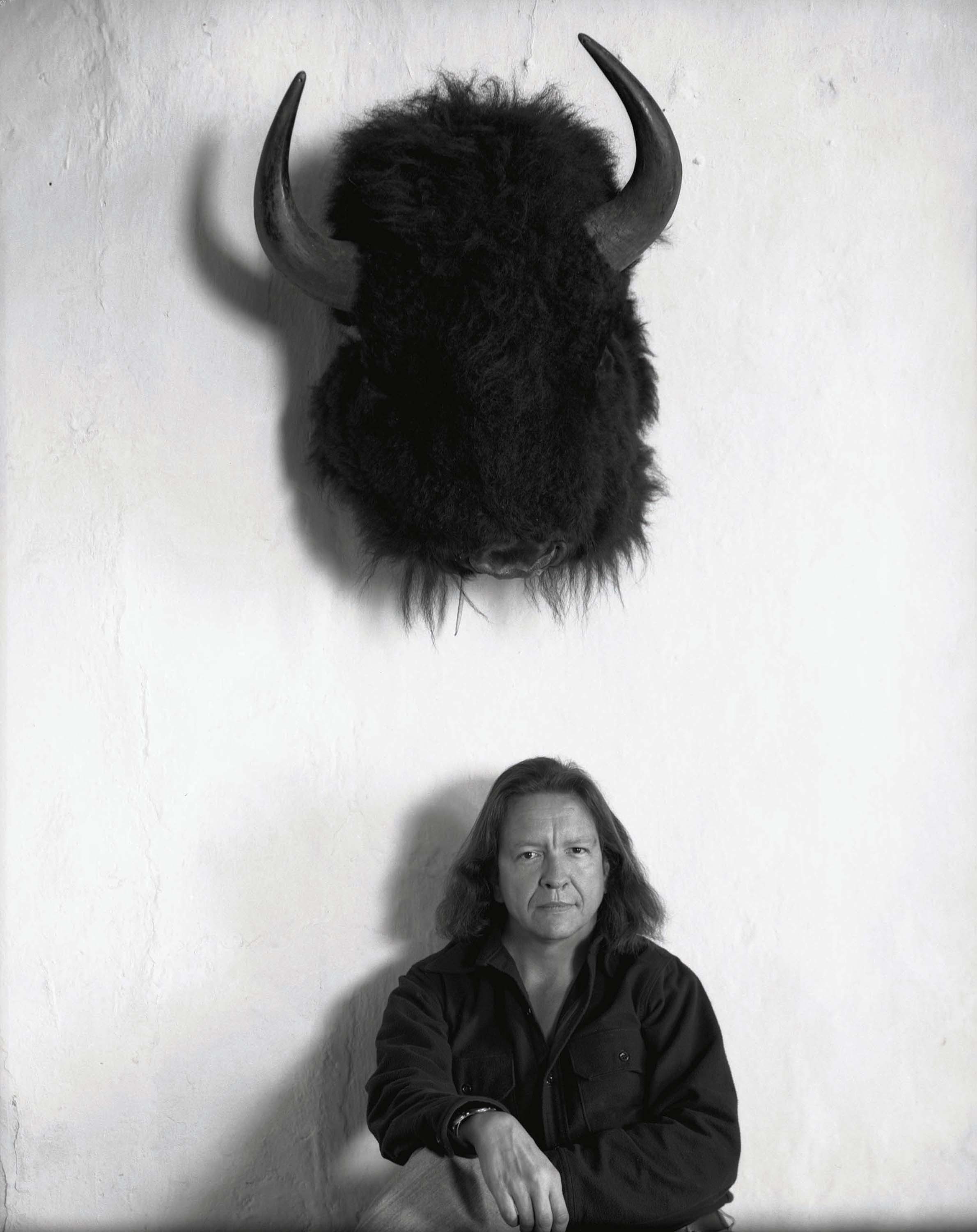

- Fritz Scholder poses with a buffalo head, Taos, New Mexico, 1977. Photo courtesy of Meridel Rubenstein

- “Indian with Beer Can” | Oil on Canvas | 1969 | 61 x 61 cm. Collection of Ralph and Ricky Lauren | Photo by Bill McLemore

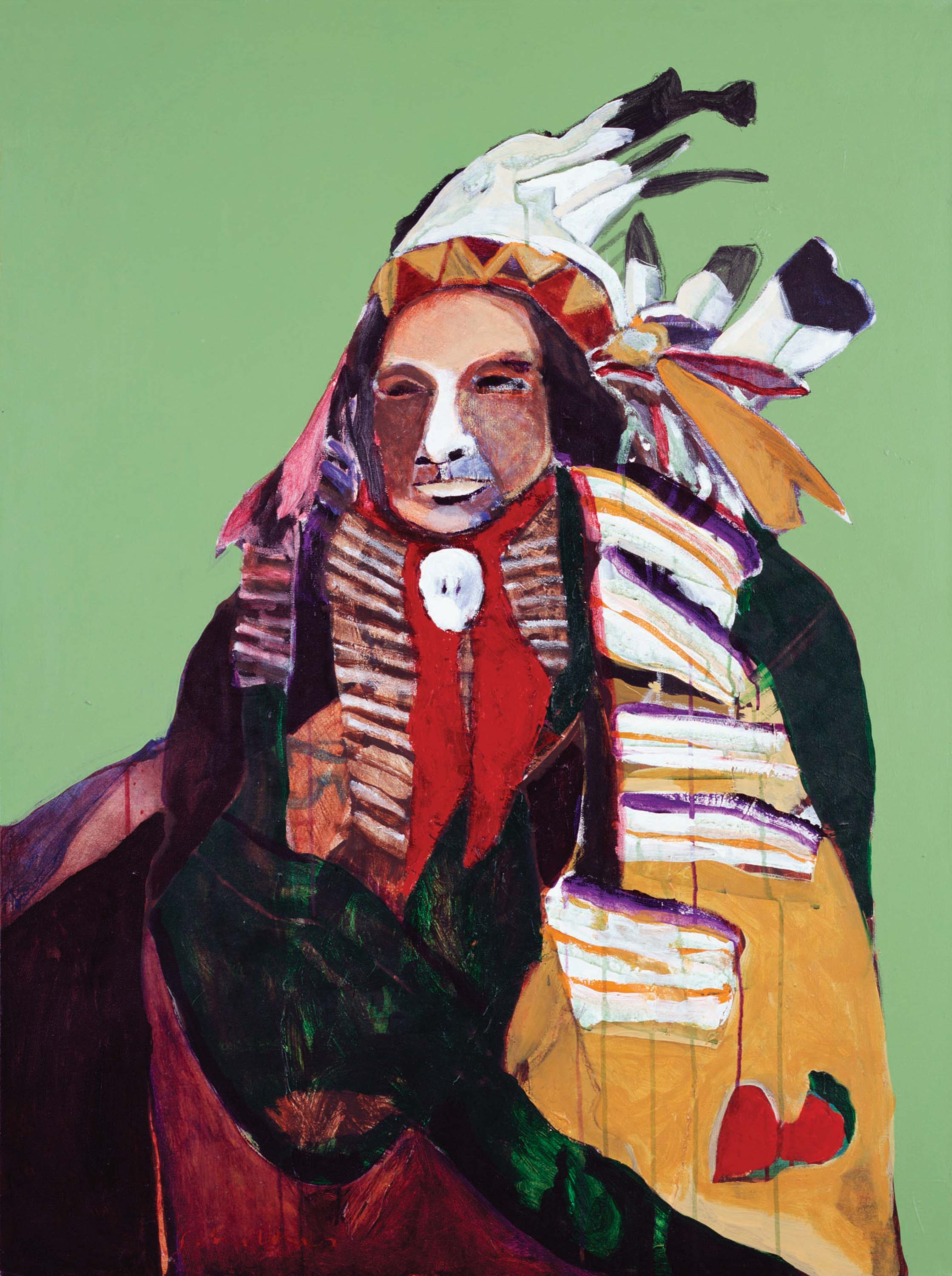

- “Heart Indian” | Acrylic on Canvas | 2004 | 48 x 36 inches | Collection of the Estate of Fritz Scholder | Photo by Hugh Talman, NMAH

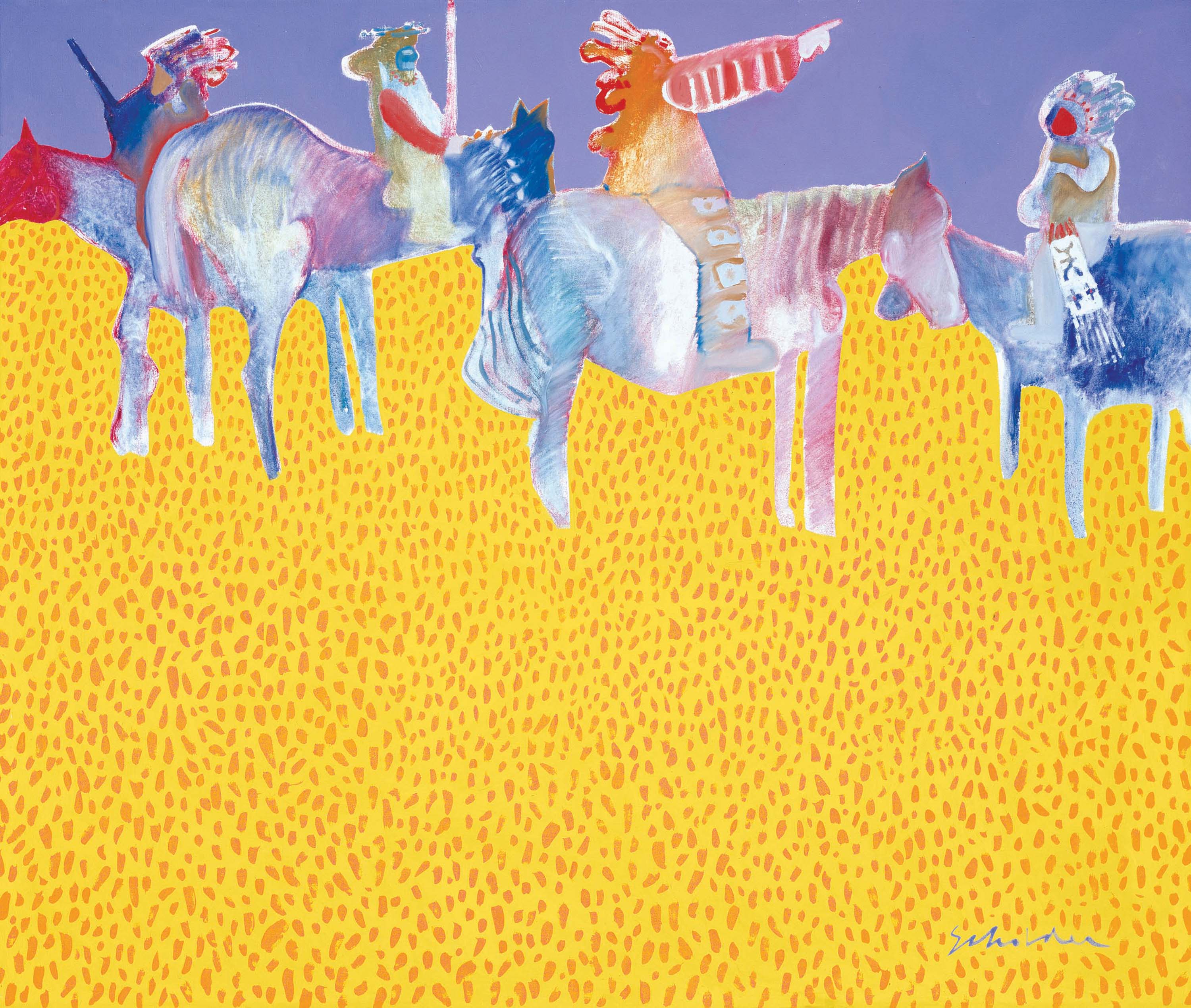

- “Hollywood Indian” | Acrylic on Canvas | 1973 | 68 x 54 inches | Larson Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

- Fritz Scholder, “Self Portrait with Grey Cat” | Acrylic on Canvas | 2003 | 203.2 x 172.7 cm. | Collection of the Estate of Fritz Scholder

No Comments