01 Sep Perspective: Gerard Curtis Delano [1890-1972]

The 20th-century artist Gerard Curtis Delano painted prolifically for more than 50 years. His subjects included cowboys, mountain men, cattle drives, wildlife, Plains Indians, Comanche and Hopi. He depicted an historic encounter between Sioux Indians and the Lewis & Clark Expedition, and he painted Mabel Dodge Luhan and her husband watching the Corn Dance at the Taos Pueblo. He created portraits, nocturnes, action scenes and landscapes. But it is in his paintings of the Navajo that Delano reached his highest expression as an artist; and it was in the Navajo and their landscape that he found his muse, as well as endless inspiration.

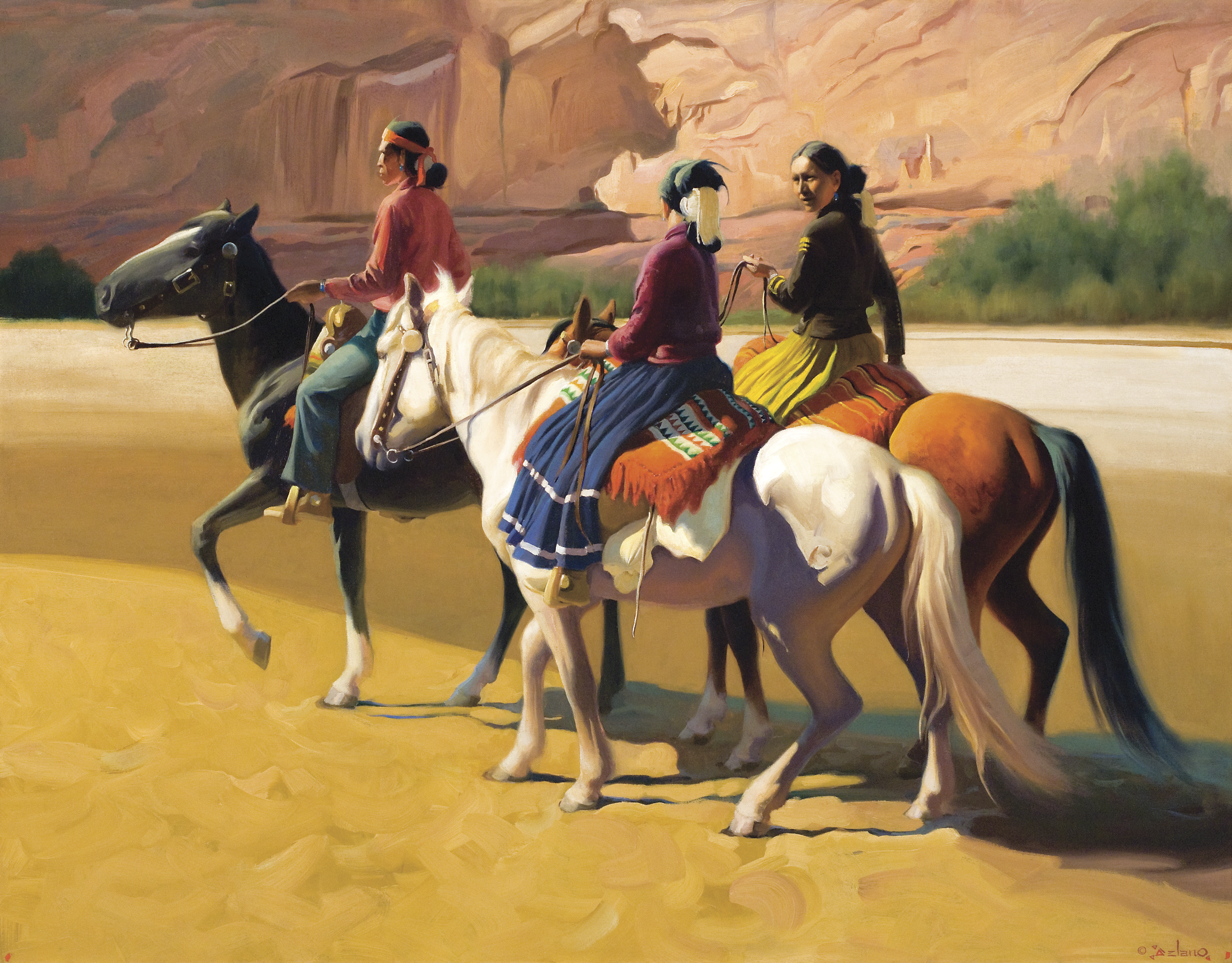

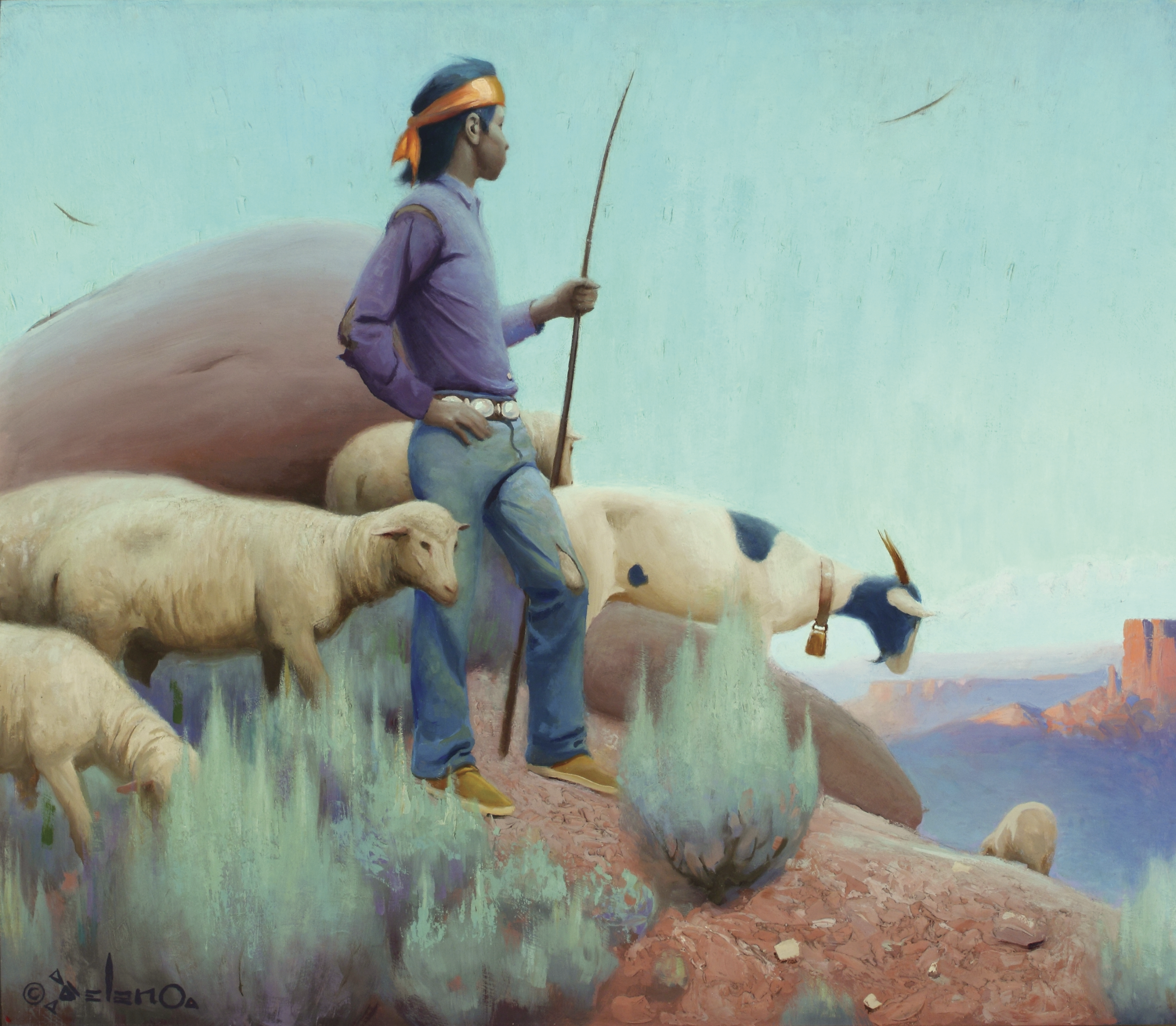

An ancient people, the Navajo during Delano’s time lived much as they had for centuries. Tending sheep, riding horses, gathering firewood, talking amongst themselves, Delano’s Navajo are depicted as calm, at ease, serene. They are comfortable with their animals, they are easy with each other, and they are at home in a fantastic, monumental landscape, under immense, everchanging skies. The artist’s style ranged from illustrative (over the years he painted covers for as many as 20 magazines) to expressive, but his works were always carefully, impeccably designed. In fact, according to his biographer, Richard Bowman, Delano referred to his paintings as “designed Realism.”

Denver-based Western art dealer Neal Smith is a longtime admirer of Delano and a dealer of his work. Smith notes, “You can’t say this about a lot of artists, particularly Western artists, but when you see a Delano, it has a totally distinctive design element that makes it instantly recognizable. It has a unique proprietary visionary quality to it. In a crowd of pictures, his is unlike anyone else’s work. It’s the design, palette and simplicity of form. They’re uncluttered and graceful. He distills each subject down to its essence.”

But, as Bowman points out, the starting point was always strong subject matter. “One thing which made Delano such an exceptional artist,” Bowman writes, “was his power in giving a vivid sense of the hidden qualities of nature. He maintained that no pictorial rendering by man can equal nature, and said that the basis of good art is forceful composition, great simplicity, and accurate drawing. An artist must know his subject thoroughly and this must come from study, observation, and insight, with a strong emotional feeling. This last is more important than mere knowledge.”

In his depictions of Navajo in their everyday activities — three mounted figures riding at an unhurried pace through a canyon setting, for instance, or two adults talking while their horses drink, or a boy standing on a knoll with his flock of sheep — Delano’s empathy and admiration for their lifestyle is almost palpable. But it is in his paintings of the awe-inspiring landscapes found in that country — sheer canyons and red rock spires, endless plains under vast skies — and the Navajo peoples’ place within it, that the emotion comes through most strongly. His large landscapes, sometimes four-fifths sky, with diminutive figures lending scale to the scene, make the heart soar.

Like many of the greatest painters of the West, Delano was born in the East, exhibited talent at a young age, and, after being advised not to become an artist by his practical-minded relatives, pursued it anyway. He studied at the Art Students League in New York City and at the Grand Central School of Art, where he took classes from illustrating greats N.C. Wyeth and Harvey Dunn, both of whom had studied under the famed Howard Pyle. From 1910 to 1920, Delano worked as an advertising illustrator, textile designer and sketcher of Fifth Avenue window displays of hats. (He also enlisted as a seaman at the outbreak of World War I.) His illustrations appeared as book covers, in railroad calendars and on the covers of such magazines as Life, Collier’s, Cosmopolitan and Western Story.

In his autobiographical essay, “My Life as an Artist,” Delano recalls that his very first sketch outside of a school assignment was of a group of Indians riding horses; he was only 4 years old. But it wasn’t until 1919 that he took his first trip west, arriving by train in Denver. A summer spent working in Denver, visiting Cheyenne Frontier Days and haying near Kremmling, Colorado, convinced the artist “that this was what I came for.” Although he would return to live and work in the East, the West exerted an irresistible pull. Over the next decade, he made several trips west, ultimately filing a claim on a homestead on the Arapahoe National Forest in Summit County, Colorado. In 1933, he moved to the West permanently.

Delano’s early years in Colorado were lean — the first two were spent near broke and in very primitive conditions on his homestead at 8,500 feet, where winter temperatures reached 40 below zero — but he kept submitting, and sometimes selling, artworks to magazines, ultimately contracting for a two-year series called “The Story of the West” in Western Story magazine. In 1940, at the conclusion of the series, Delano offered a collection of paintings and sketches to the Cyrus Boutwell Gallery in Denver. Boutwell sold them, but at prices Delano considered low. From then on, Delano was a gallery artist, but from that time he was always involved in setting his own (almost always very high, for the times) prices.

In 1943, Delano visited the Southwest and encountered the Navajo people for the first time. Later he wrote, “Here was a beautiful, proud people who, in everyday life, dressed more colorfully than any other tribe of my knowledge.” Thus was Delano set on the course he would follow for the rest of his career.

Neal Smith first saw Delano’s paintings in the late 1960s. “I was totally enchanted by them,” he recalls. “It was before any developed market for Western art, and he had his paintings in a Denver floral shop. You’d see these beautiful paintings amidst all these cut flowers. He had an itinerant dealer who placed them in restaurants and places in the high country, [so you’d find them in] some greasy spoon in Kremmling. He set the price and there wasn’t any budging from that. They were way beyond my means at that time.”

At times Delano’s high prices frustrated both the artist and his galleries, but he believed in his own worth. He married twice and always made a living, if not what he thought he deserved. Ultimately, his belief that his paintings would only increase in value was proven correct.

“Since I evolved into a dealer of paintings in the mid-’80s,” Smith continues, “I’ve been exposed to a couple hundred Delanos and I’ve seen the market [skyrocket]. Delano was, in a way, out in front of the Western art boom of the late ’60s. He was subsequent to the Taos Founders and Santa Fe artists, but he’d completed the great body of his work before the founding of the [Cowboy Artists of America] in 1965. But make no mistake, when you look through [to see who had] his mounted Navajo paintings, the people who had them ran the most prestigious galleries in the business. By the end of his career he had achieved major fame.”

In recent years, Delano’s paintings have only become more sought-after. In 2008, an oil called The Navajo, which the artist considered one of his best, sold at auction for $1.4 million to the Anschutz Collection. The painting depicts three colorful mounted figures oriented slightly away from the viewer riding at a relaxed pace; the two women are chatting, a vertical canyon backdrop behind them. Like all Delano’s Navajo paintings, the subjects are not just comfortable in their environment, but are one with it.

Gerard Curtis Delano was a devout Christian who believed strongly in his own God-given gift. “Asked for my philosophy about my work,” he wrote, “I say simply that I feel I have been given a great talent in order to give beauty to the world.”

Delano’s depictions of an instinctively elegant people are sensitive and richly detailed. His paintings of the Navajo living, riding and herding sheep amidst the spectacular scenery of sheer-walled canyons, monumental rock spires and vast open plains beneath dramatic cloud formations are truly exhilarating.

As for the Navajo, they accepted Delano in their midst; they referred to his paintings as “Walking With Beauty.” In Richard Bowman’s 1990 book of the same name, he quotes Delano as saying, “There is a vastness, an immensity, and the peaceful hush of an enormous cathedral about Arizona’s great canyons. Whoever has been within these walls and has seen the flocks of sheep and the goats grazing, heard the distant tinkle of the lead goat’s bell, listened to the haunting song of the bright-skirted shepherdess, and who has seen in the distance an approaching rider, a tiny speck against the massive walls, must yearn to perpetuate his impressions of those precious moments. That is why I paint the Navajo.”

Chase Reynolds Ewald writes about art, design, food and travel, covering the American West from her home in northern California. Her most recent book is The New Western Home.

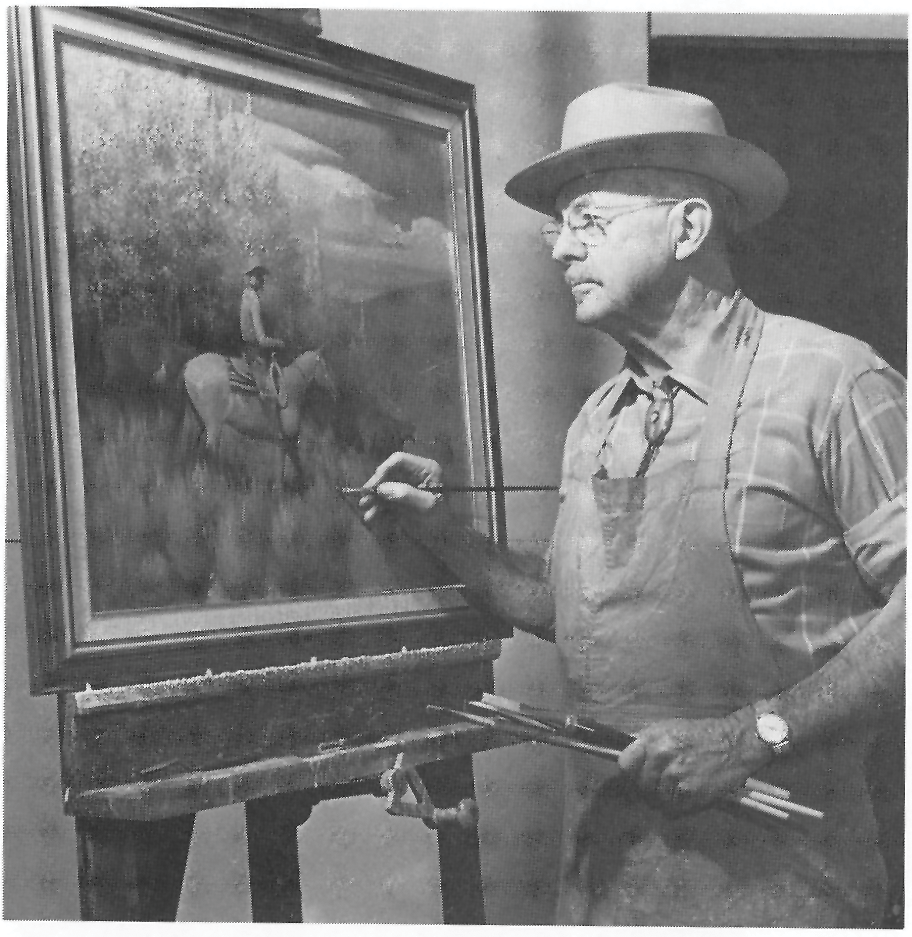

- Artist’s portrait of Gerard Curtis Delano — as published in Walking with Beauty

- “Cattle on the Range” | Oil | 9 x 12 inches | Private Collection | Photo courtesy Neal R. Smith Fine Art, selected for a forthcoming exhibition at the Denver Art Museum

- “Navajo” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 46 inches | Courtesy of the Anschutz Collection

- “Sunset Silhouette” | Oil | 20 x 24 inches | Private Collection | Photo courtesy Neal R. Smith Fine Art

- “Navajo Shepherd” | Oil | 24 x 28 inches | Private Collection | Photo courtesy Neal R. Smith Fine Art

No Comments