01 Sep Perspective: Hans Kleiber [1887-1967]

“I had gone into forestry for the pure love of it. My years of work for the [United States Forest Service] filled a niche in my life that nothing else could have filled with deeper satisfaction and enjoyment.”

How many collectible fine artists in the American West attribute the crux of their creative endeavors to a remote posting in civil service, callousing their hands with axe, trenching fire lines with Pulaski and stringing together pack mules to inventory natural resources in the backcountry?

Not even Charlie Russell or Thomas Moran, the latter famously an artiste-de-camp for the Hayden Expedition in Yellowstone, possessed such rough and tumble credentials.

Kenneth Schuster, director of the Bradford Brinton Museum in Big Horn, Wyoming — one of the sweetest provincial destinations in all of the West — shares this observation: Of the early 20th century artists whose careers emanated from Wyoming, Schuster regards Elling William “Bill” Gollings (1878 – 1932), who had a studio in neighboring Sheridan, as the most prominent.

Next to Gollings, however, Schuster considers Hans Kleiber (1887 – 1967), who shared the above confession as the state’s greatest non-cowboy artist of his time.

For those unaware of Kleiber (pronounced Kleye-bur), he was not a sculptor. As a self-taught oil painter and watercolorist, his execution could be described, on his best days, as inspiring; on his worst, as naïve if not uneven and mediocre.

The German immigrant who found his way to Wyoming in 1906, never had the luxury of attending a distinguished art school. Instead, his formative years were spent in the boondocks as a Forest Service ranger dispatched to the North Woods of the Upper Midwest, the northern Pacific rainforests and throughout the evergreen canopies that carpeted the high country rising beyond his Wyoming porch stoop.

Kleiber’s status as a regional artistic folk hero stems from his close association with a medium that has earned him comparisons to Edward Borein (1872 – 1945). His métier was etching, the age-old process of printmaking embraced by Michelangelo, Rembrandt and countless others.

Kleiber’s prolific output and the statements he made with simple lines, Schuster says, are the reasons that he is remembered today as “The artist of the Big Horn Mountains” — no small accolade considering the prominent group of painters affiliated with this spur-range of the Rockies. In fact, he is credited with teaching Gollings how to etch.

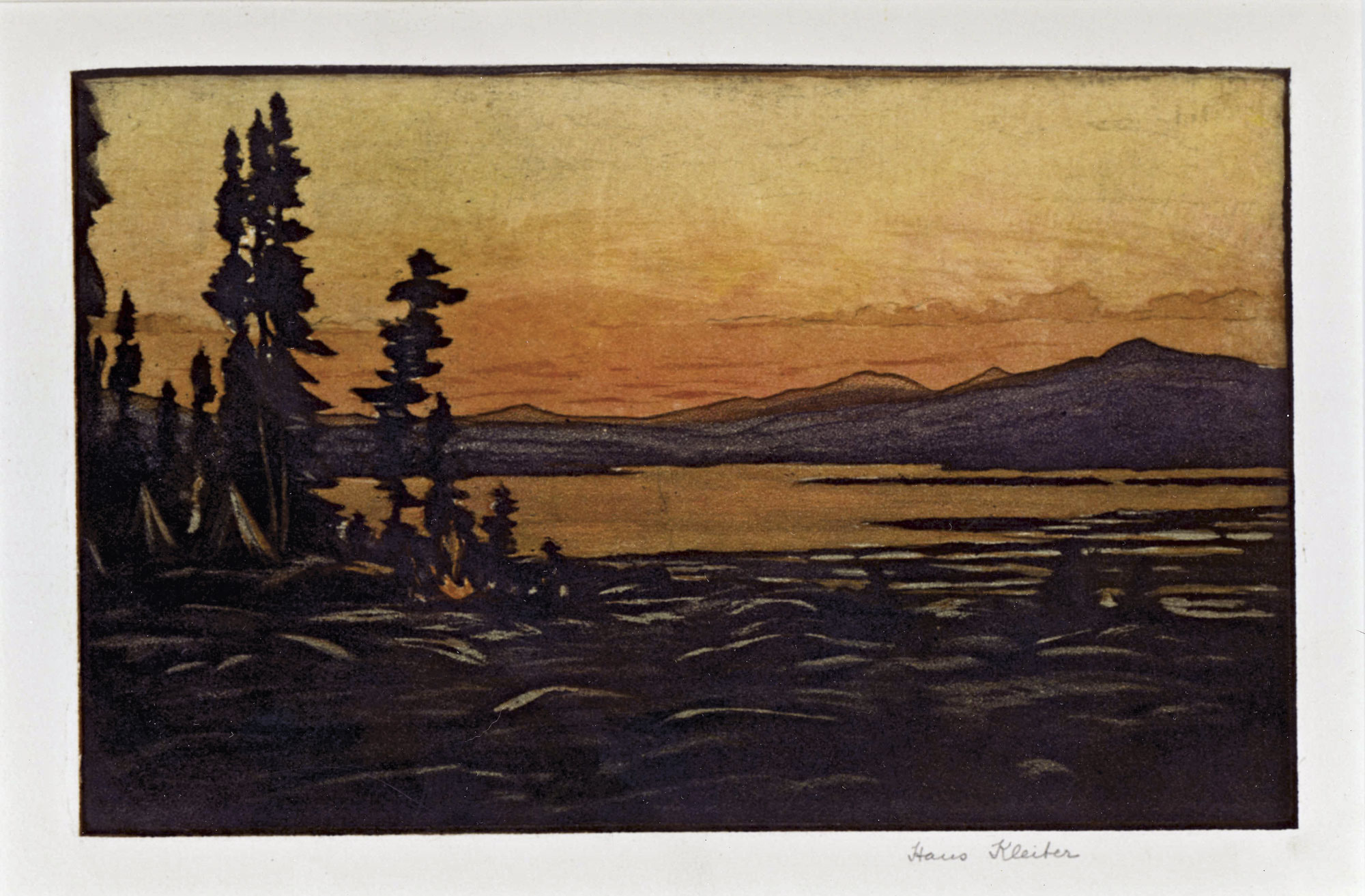

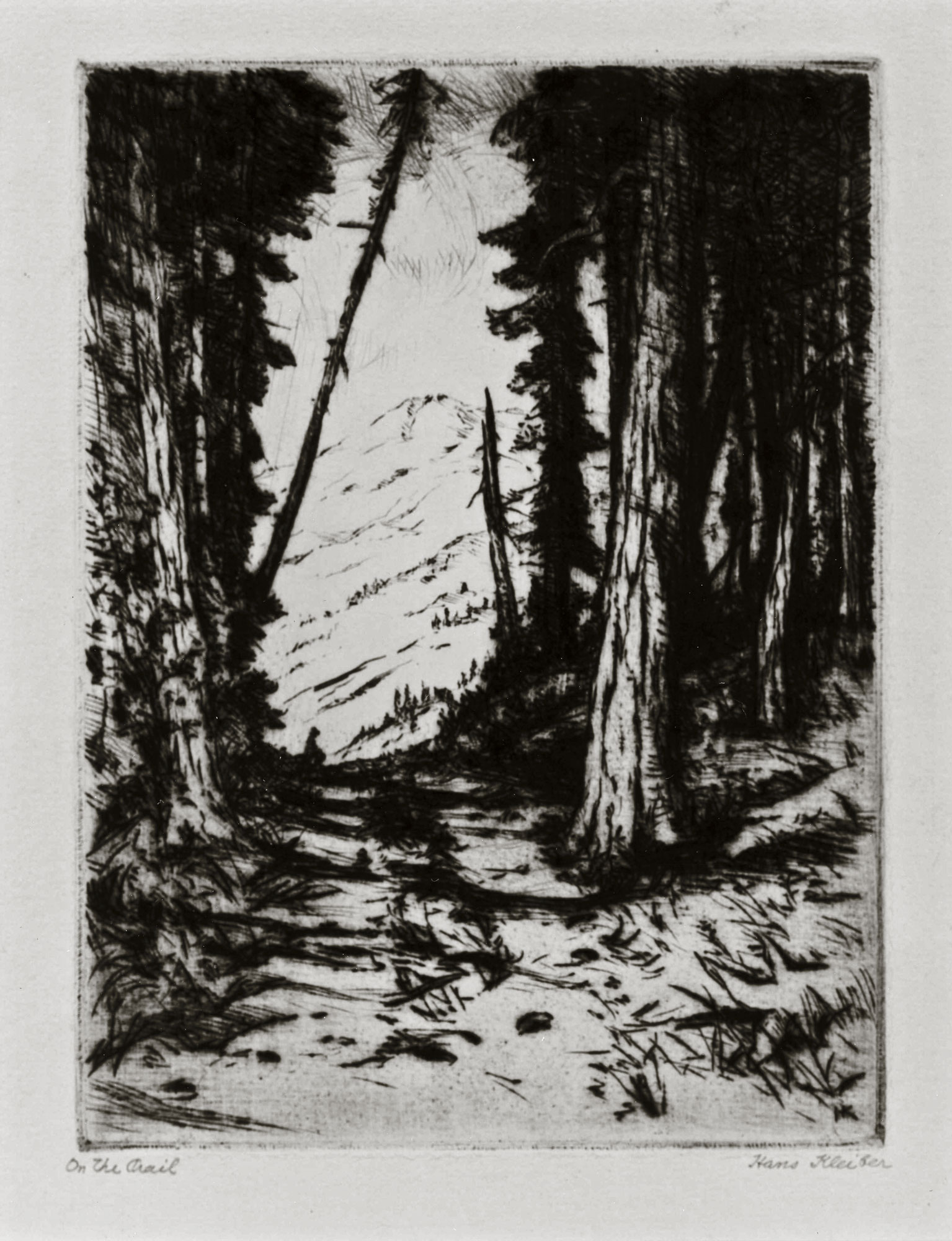

Kleiber’s rustic scenes of angling, birds in flight, big game animals, camping and mountain vistas, including such two-ink nocturnes as Late Arrivals and Evening At Elk Lake — Wyoming, are classics. His pastorals, such as The Old Cottonwood Tree, exude a kindred connection with European engravers from the 17th and 18th centuries. His piece, On the Trail, is a pathway into a fairy tale.

Another defining feature is that entries pulled from Kleiber’s journals reveal him as a sensitive, aesthetic-minded writer as well as a poet. His ruminations about the interconnections of ecology and the value of wild places rival those of better-known Forest Service alums Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall.

“Kleiber breaks the mold of a person who would be considered the stereotypical Western artist,” Schuster notes. “He had a calling to art at an early age and then put it on the backburner. Decades later, he returned to it as his first passion.”

Kleiber’s etchings and paintings can be found in major private and public collections. The University of Wyoming Art Museum has more than 400 works; the Bradford Brinton has a sizeable number of pieces, including several commissions; the Buffalo Bill Historical Center’s Whitney Gallery of Western Art in Cody has an extensive Kleiber archive; and in tiny Dayton, Wyoming, Kleiber’s historic log cabin studio is a tourist attraction along Main Street.

Just the other day, while strolling through the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, this writer noticed a Kleiber western scene hung at the back of a gallery that featured epic paintings by Wilhelm Kuhnert, Richard Friese and Carl Rungius.

What remains indisputable is that Kleiber’s years in government uniform and his Old World romance gave him an uncommon feel for the West, earning him a showing at the Smithsonian in 1944.

Despite his geographical isolation — though evidence shows he was influenced by a number of painters and the sporting motifs of etchers Frank Benson and Richard Bishop — Kleiber delighted in experimentation. He routinely combined pure etching with drypoint, pen-and-ink and aquatint techniques to achieve fuller visual effects.

Accompanying the Kleiber mystique is an equal measure of posthumous intrigue, parallel in many ways to the discussions surrounding the authenticity of intaglios by artists ranging from Borein to Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso.

In the early 1990s, Marylee Moreland and her husband, Gary Temple, were, like many collectors of Kleiber’s hand-pulled lithographs, smitten and yearning for more information. The Montanans operate Meadowlark Gallery in Billings, one of a handful of art dealers who specialize in Kleiber etchings.

Their curiosity was piqued at the discovery of inconsistencies in Kleiber’s images that could not be explained away simply as nuances inherent to the etching process. They also uncovered alleged Kleiber signatures that were suspect and may have been added to pieces when plates from the artist’ s popular Frontier Series were re-struck following his death.

Not only does the Moreland-Temple book, Hans Kleiber: Wyoming Printmaker and Artist, provide the most extensive accounting to date of Kleiber’s hundreds of etchings and paintings, but it serves as an essential reference for established and new Kleiber collectors.

What gives etchings their charm is not reproductive perfection like that associated today with modern state-of-the-art printers; actually, quite the opposite.

A copper plate surface transmits faithfully only a finite number of surface impressions, exacted from the original drawing, before it wears smooth and goes “blind.” Moreover, each time ink is applied to the plate by the artist or master printer and then pressed, it scores the paper with subtle differences. This lack of uniformity, from the first print to the last, actually makes every piece one of a kind.

By tradition, the artist inspects each piece. His or her stamp of approval is putting it into circulation after signing one’s name in the margin, allowing the viewer to know it was touched and met with a discerning gaze by its creator.

As fine art pieces, etchings generally are less desirable collectibles when compared to original paintings and bronzes. The market prices them accordingly. In the case of a Kleiber etching, that may have a few hundred in the edition, smaller format pieces with modest frames can often be acquired for $500 to $1,000.

But, at the same time, etchings, even open editions as Kleiber produced, are held in far greater esteem than the much maligned modern “limited edition” art reproductions churned out in edition sizes that can reach tens of thousands (if not more) and, in reality, are little more than non-distinct decorative posters with the artist’ s autograph. Certainly, the resale value of many historic etchings has withstood the test of time.

Temple doesn’t blame Kleiber, an artist struggling financially, for exploring myriad ways to get his images placed before the public where he could derive an income from sales. That’s why Kleiber agreed to have the New York City-based Associated American Artists (AAA), working in partnership with Anderson-Lamb Photogravure Corporation, market and distribute pieces that he signed and titled in his own cursive handwriting. He had agreements with other establishments in Boston and Detroit, too. Kleiber also printed and sold pieces locally at dude ranches, including Eaton’s Guest Ranch in Wolf, Wyoming, that attracted clientele from around the world.

Temple and Moreland embarked upon a quest for answers after they noticed that some of the same Kleiber images were reproduced in slightly different sizes and assumed by collectors to be etchings when actually they were photogravures. The classic Winter In the Big Horns, featuring elk, was one of Kleiber’s most popular and was reproduced both as an etching and photogravure. Photogravures distribute ink more uniformly onto the paper.

Temple recalls a Borein seminar at the annual C.M. Russell Museum Show and Auction in Great Falls, taught by the late Harold Davidson. He heard an earful about what Davidson called “the brotherhood of forgers, fakers and crooks” preying upon unsuspecting collectors by printing up copies after an artist’s death and forging the signature. The Dali print market is notorious.

Davidson had extensive experience authenticating fine art, especially with Borein prints. “After talking with him, I became an art detective,” Temple says, explaining that he consulted with a number of forensic authorities, including experts in handwriting, paper dating and copper plates.

“Forgeries are not the present problem in the Kleiber market, but rather the sorting out of some of the posthumous activities that have occurred since his death in 1967,” Temple adds, noting some controversy surrounded Kleiber plates.

The irony of issues relating to Kleiber after his own passing is that Kleiber himself, following his friend Gollings’ death in 1932, ensured that Gollings’ etching plates were cancelled, thereby preserving the integrity of the editions.

“Collectors should always know what they are buying, what a piece is, the size of its edition if possible, the kind of paper it was printed on, the history of the work after it left the artist’ s hands,” Temple says from Meadowlark Gallery with an extensive array of Kleibers behind him.

“Even if they can,” Temple adds, “they ought to try and find out how a piece is framed and why it is framed a certain way because it can help confirm its authenticity. They should never be afraid to ask questions. Not only does it protect their investment but the journey it takes them on can be fun.”

The back stories of Hans Kleiber’s diversity are proof.

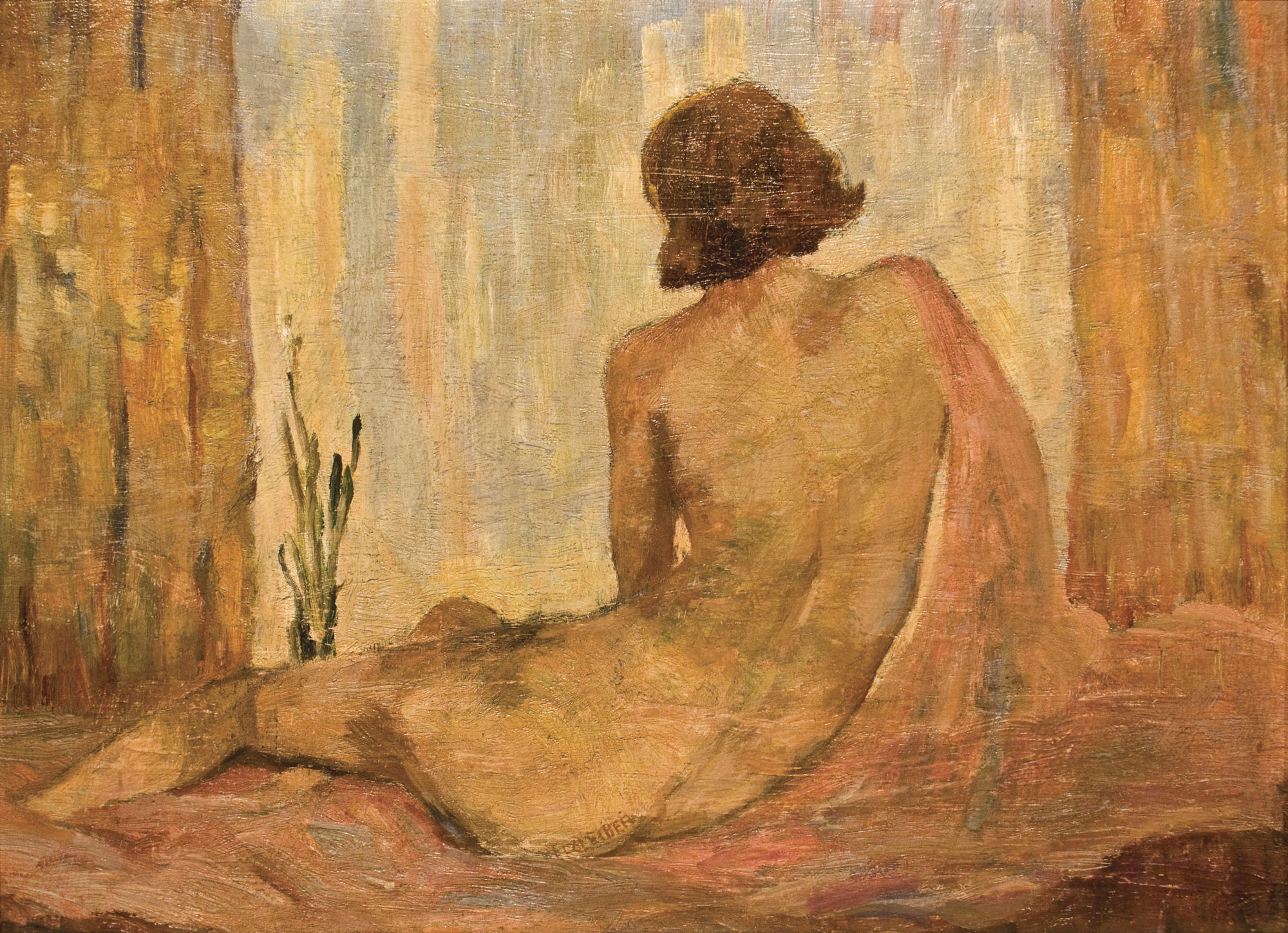

Beyond etching, Kleiber exercised no restraint with both palette and design as a nature painter. He also studied the human figure. Although his wife, Missy, reportedly was not happy with his desire to draw nudes, he seized upon every opportunity.

A testament to his penchant for traditional painting and his mischievousness is a double-sided oil that features Untitled Landscape on one side and, for those who are aware of it, Untitled Nude on the other.

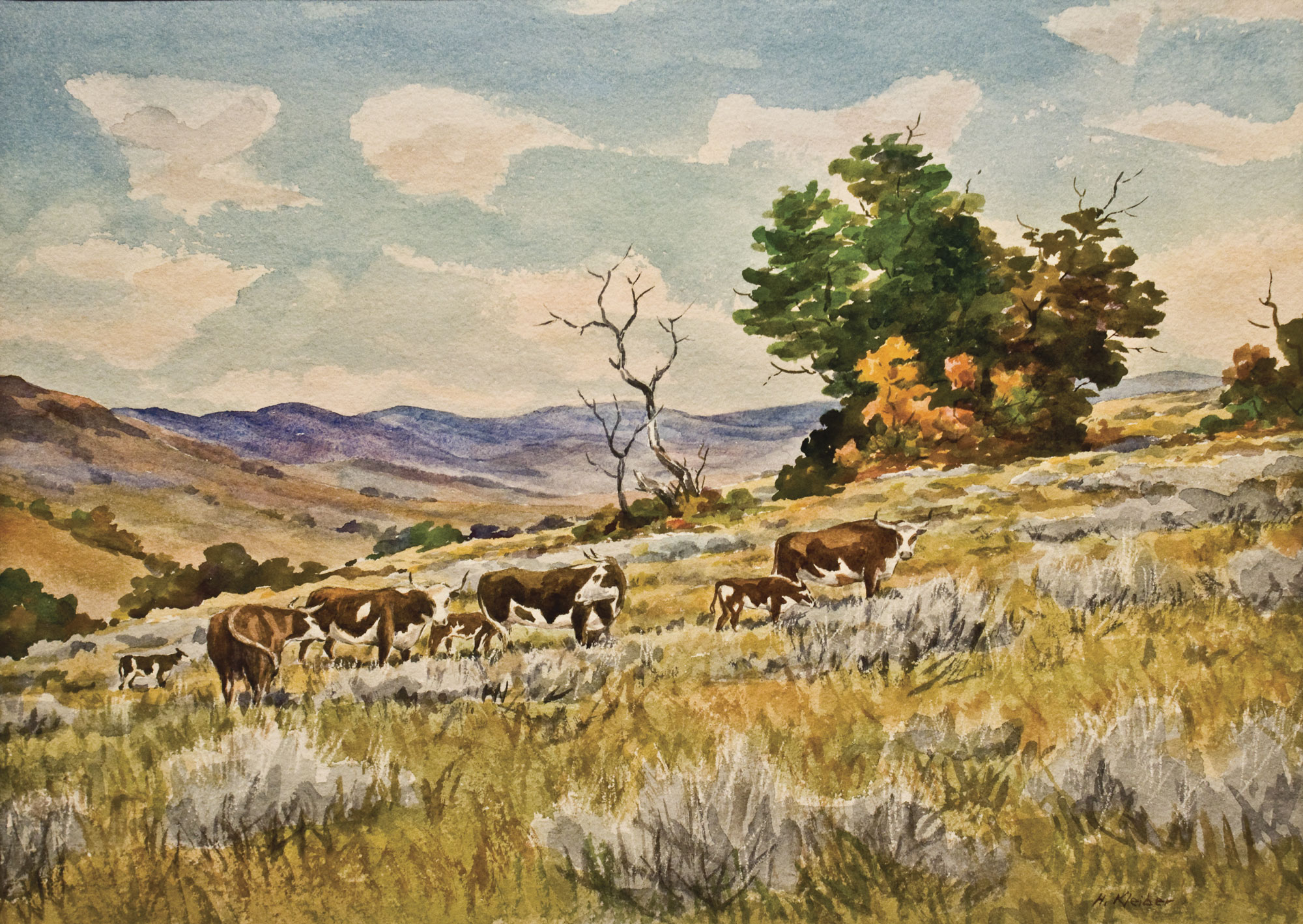

Demonstrating his versatility, Cows and Calves on the Reservation speaks to Kleiber’s better outings with watercolor.

Sheridan-area painter and etcher Joel Ostlind is regarded by many to be Kleiber’s modern artistic heir and he commands a growing following just as Kleiber did, says Susan Simpson Gallagher at her gallery in Cody. Ostlind has studied Kleiber’s remarkable ability to impart the illusion of texture and Ostlind himself is praised for using negative space to convey a depth of field flowing off the copper plate, she says.

In the latter years of Kleiber’s life, when the meticulous mastery of his etching was compromised by declining eyesight, Kleiber applied his watercolor brush to several scenes on paper. The hand-tinting bestowed a few etchings with a fresh face and yet another dimension of collectibility.

In 2007, the Wyoming Game & Fish Department named Kleiber to its “Outdoor Hall of Fame” where he joined the likes of sportsman-broadcaster Curt Gowdy, Olaus and Mardy Murie, President Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell and Jim Bridger, among others, as people who contributed to global appreciation for Wyoming’ s natural heritage.

Still, because Kleiber wasn’t an accomplished oil painter, he has been sold short in history, Schuster says. But then again, there are numerous, better established names in the pantheon of 19th- and 20th-century Western art who couldn’t create a fine etching, he notes.

“When you consider Hans Kleiber’s innate, self-evolved talent, and how far he came without the advantage of instruction and sponsorship that many of his contemporaries had, he was a very fine artist who found his voice as an etcher,” Schuster says. “It’s how he translated his love affair with the outdoors that makes his work something people want to have on the wall.”

Todd Wilkinson has been writing about people and places in the American West for the last three decades, though assignments have taken him around the world. The Bozeman, Montana-based author is currently at work on a book about media mogul, bison rancher and environmental humanitarian Ted Turner.

- “On the Trail” | Etching | 6.8125 x 5.375 inches

- “The Old Cottonwood Tree” | Etching | 7.125 x 10.75 inches

- “Reclining Nude” (two sided painting, below, reverse side of painting) | Oil | 9.75 x 13 inches

- “Reclining Nude” (two sided painting, above, reverse side of painting) | Oil | 9.75 x 13 inches

- “Cows and Calves on the Reservation” | Watercolor | 10.375 x 14.5 inches

No Comments