09 Jun Perspective: Julia Morgan [1872-1957]

In December of 1972, Tony and Trish Hawthorne purchased a home in Berkeley, California, to accommodate the needs of their growing family. When told their 1920 house was designed by the late Julia Morgan, the ingenious architect behind Hearst Castle, they were overjoyed. But there was one problem. They had no proof. Was the two-story English Tudor truly from Morgan’s original blueprints or an urban legend handed down from one owner to the next?

Thus began Trish Hawthorne’s quest over the next eight years, interviewing previous inhabitants, poring over archives and contacting every source she could think of. One day the call came, and Sara Boutelle, the author of the definitive book Julia Morgan, Architect substantiated the claim after locating Morgan’s client list and the addresses of her projects. “It was June 1980, and I was in the kitchen,” recalls Hawthorne. “When Sara told me she found it, I was just dumbfounded.”

For Hawthorne, tracing the works of Julia Morgan has fueled her passion to know more about this progressive individual, and for obvious reasons. The San Francisco architect, always addressed as Miss Morgan, was born in 1872 during the Victorian era when women were discouraged from pursuing careers.

Buoyed with support from her devoted mother, Miss Morgan broke away from all convention and became California’s first licensed female architect. Exceptionally prolific in a 42-year career that spanned nearly the first half of the 1900s, she tackled every type of commission imaginable: castles, churches, mausoleums, schools, hospitals, women’s social clubs, mansions, middle class homes and more. Art historian Mark Wilson and author of the newly revised book, Julia Morgan, Architect of Beauty, states that by the time she died in 1957 at age 85, she had completed more than 750 buildings, the majority of them in California. This number exceeded that of the famous Frank Lloyd Wright, who completed 532 buildings in 66 years.

Quiet in manner, this unlikely feminist, donning skirts and silk blouses, was driven by her work, refusing to bask in the glow of media attention. She rarely granted interviews and never submitted articles to architectural periodicals even though newspapers enjoyed writing about her accomplishments. Largely overlooked after her retirement, she was regarded as a second-rate architect even in the 1960s and 1970s, recalls San Francisco architect Bobbie Sue Hood of Hood Miller Associates.

Today, 55 years after her death, her influence and stature is more pervasive than ever. She is the subject of books, articles, college courses and even a play titled Becoming Julia Morgan.

And her contribution to the world of architecture is finally getting its due. In 2008, she was inducted into the California Hall of Fame in Sacramento. This year, California Cultural and Historical Endowment’s Landmarks California program will present Julia Morgan 2012, a six-week festival to commemorate her achievements. In the years that follow, other subjects will be honored. That Morgan was selected first to kick off this annual celebration is not surprising.

After all, in 1904 she became the first female architect in California to own her own practice. Prior to that, she was the first woman to enter and obtain an architectural certificate from the renowned Ecole des Beaux-Arts design school in Paris. Earlier, she graduated as the only female with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from UC Berkeley, notes Dr. Karen McNeill, art historian and Julia Morgan expert.

Miss Morgan is now hailed as a pioneer in eco-friendly building and construction. “Her sensitivity to using local resources, using natural lighting and airflow had a sense of greenness to it that made her ahead of her time,” says Mimi Morris, executive director of the California Cultural and Historical Endowment.

In her prime, she toiled as long as 18 hours a day, sustained by her favorite vices: coffee and candy. Dedicated to her career, she never secured any romantic entanglements, but historians report she was close to her parents, siblings and office staff. She became godmother to several of her workers’ children and was known to keep candy in her top drawer for them.

Though slight in stature, at 5 feet tall and 100 pounds, Miss Morgan was revered by colleagues, staff, contractors and artisans. She held high standards when it came to excellence in the broad picture and in the specific details. She would not hesitate to walk on a roof as she did at the YWCA conference grounds (now Asilomar) in Pacific Grove, probably to examine the construction of the stone chimney, notes California State Park Ranger Roxann Jacobus, who gives property tours.

At the Merchants’ Exchange Building, where she had her office in San Francisco, Miss Morgan stood on a scaffold 13 stories high to inspect building cracks in the terra cotta, reports art historian and author, Mark Wilson. During construction of the Fairmont, she scrambled up extremely high ladders for a close-up look at the intricate ceiling, faux marble pillars and Rococo molding, according to Wolfe. Such compulsion for exactness became her hallmark, and Morgan became known as the “client’s architect.”

Adept at sketching, Morgan often drew illustrations and specifications for interior accessories such as furniture and table china, which was the case at the Berkeley Women’s City Club. (She also designed many YWCAs and women’s clubs to support their causes, often making little profit.)

What propelled her popularity can be attributed to structures at Mills College in Oakland. When the 1906 earthquake and fire devastated San Francisco and buffeted the Bay Area, the Mills College bell tower and library remained unscathed. Morgan’s tower and library was made of reinforced concrete, a structural methodology rarely used at the time. Today, her notes on how to pour and mix concrete are still on record. “I once read her recipe for concrete that involved mixing in horse hair,” says Jacobus.

The bell tower and library achievement led to her commission to rebuild the quake-damaged San Francisco Fairmont. Today, the structure remains one of the most resplendent historic hotels in California.

The “client’s architect” was not without criticism, however. In the years following her death, some architectural historians grumbled that her work lacked imagination because she did not forge a signature style of her own, notes Wilson. Instead, she often blended architectural styles. With the Hawthorne house in Berkeley, the exterior is distinctly English Tudor, while the interior is Arts & Crafts with plaster walls, redwood trim and symmetry throughout. Says Dr. McNeill, “She could have had her own architecture style. Very early on, she worked with clients to produce buildings to accommodate their budgets and suit their needs.”

In Morgan’s social halls, she transformed voluminous areas into places that exuded intimacy. “She gave great thought about how to bring people together in public and private spaces,” reports Morris. Meeting rooms showcasing lofty ceilings with exposed beams often feature a grand fireplace, board-and-batten walls and handmade wrought-iron chandeliers.

Says Wolfe of the Fairmont Hotel, “When you come into our magnificent lobby, you have a sense of grandeur, and people truly feel that they have arrived. The lobby has lots of nooks and crannies where people can meet and hold interviews or come by themselves and have total privacy.”

And while she did not conjure up her own architectural form, Miss Morgan repeatedly employed motifs of children, birds and flowers in elements such as carved doors, concrete pillars and fireplace hearths. “Whenever I give Julia Morgan tours, people always say, ‘Wow!’ They are in awe when they look around at all the details. She had a pleasing sense of sophisticated elegance,” says Wilson.

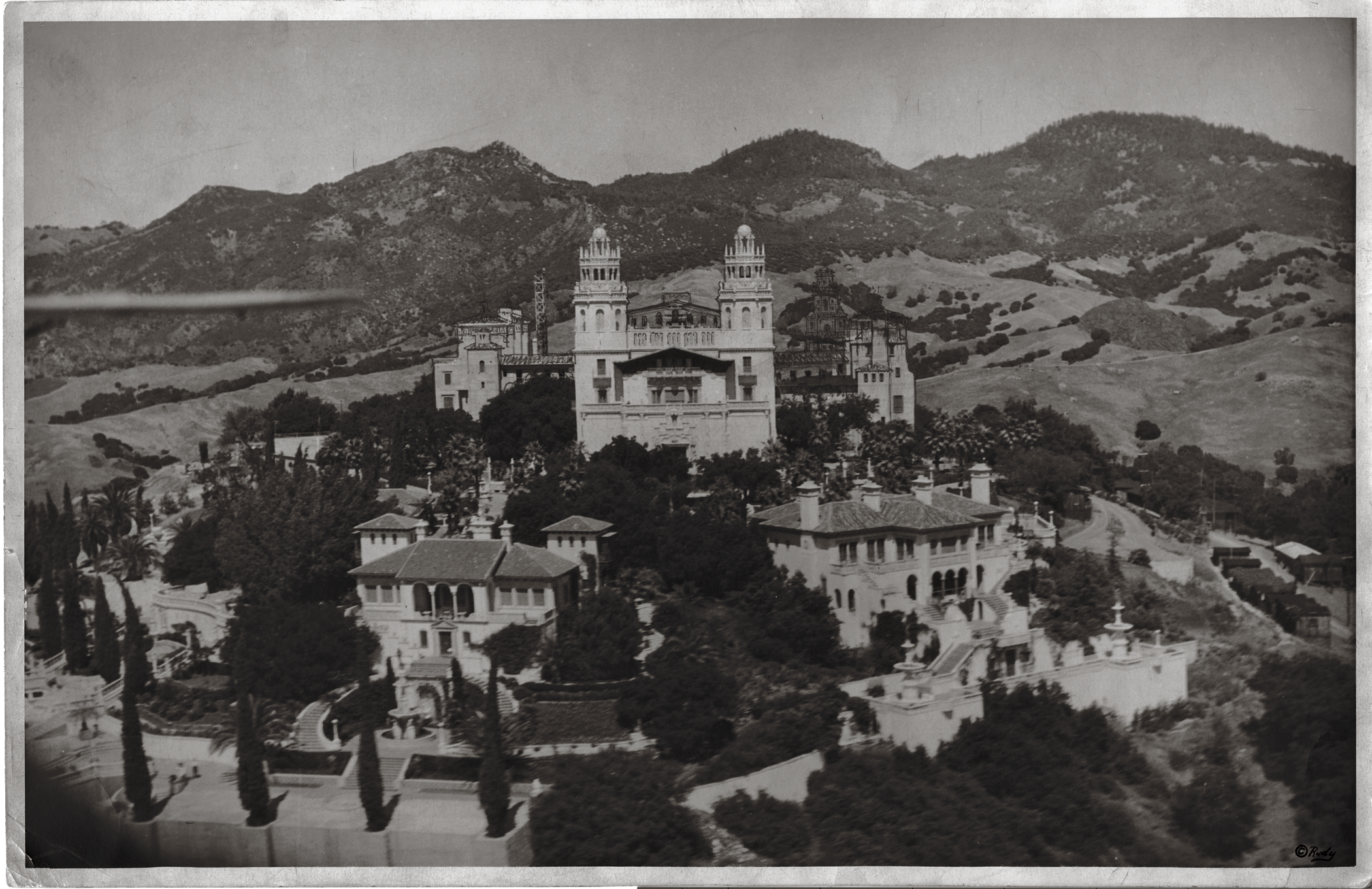

According to Wilson, critics once charged that she yielded too much control to clients, especially when it came to working with the infamous William Randolph Hearst on Hearst Castle, a project that took 28 years to complete. It is by far her most popular and publicly visited accomplishment.

Wilson stresses that in contrast to such criticism, early letters from Hearst to Miss Morgan reveal that he valued her ideas and that the castle was “a joint effort between two creative and visionary individuals.” This petite professional, acknowledges Wilson, was able to stand toe to toe with a very powerful figure who sported an equally powerful ego.

Although she graduated from UC Berkeley and completed an impressive body of work, after her death Julia Morgan was a name rarely mentioned, if at all, in the UC Berkeley classrooms. In the 1970s, professors railed on about the achievements of Frank Lloyd Wright and his male counterparts as a plethora of Miss Morgan’s churches, houses and social clubs stood in their glory within blocks of campus.

Jacobus notes that it wasn’t until 1988 — when art historian Sara Boutelle published the 272-page, 4-pound treatise Julia Morgan, Architect — that posthumous prominence found this consummate perfectionist. When Boutelle went to Hearst Castle for the first time in 1972, docents did not know who the architect was, and most guessed it was a man. That began her sleuthing effort to unravel the mystery of the unknown architect. “It was a hard sell for her to even get the book published,” says Jacobus. “Nobody thought much of redwood or stucco buildings. These kinds of structures didn’t fall into the limelight.”

Today, Miss Morgan’s status among architects, and particularly female architects, is evident: Julia Morgan is a hero. Bobbie Sue Hood, who has spent 20 years researching her life and career, was first drawn to Morgan’s work when she wandered into St. Johns Presbyterian Church in the 1970s, and was overwhelmed by the minimalist elegance of the redwood interior, light fixtures and benches.

“I like the way she used light to punch up parts of a building,” she says. “I like to bring light into the interior of a building with skylights or windows to provide a central focus. It turns a modest house into something luxurious.”

Although some of the architect’s works have been demolished, many remain standing and several buildings have been repurposed. The summer compound for 1930s movie star Marion Davies is now the Annenberg Community Beach House, a public swimming pool and meeting facility in Santa Monica. A 1918 YWCA Hostess House is MacArthur Park Restaurant in Palo Alto, which maintains its charm with open beam ceilings and brick fireplaces at each end. And another YWCA was reborn as the Riverside Art Museum after a restoration campaign in 1995. After all these years, “her buildings are still standing, converted for another use without significant changes,” marvels Berkeley architect, Sandhya Sood, principal of Accent Architecture + Design.

“Her work is so relevant today,” says Sood. “Her work is crisp and clear. She used durable, honest materials like stone, wood and brick, and everything was local.”

Case in point: To build the YWCA conference grounds in Pacific Grove, Morgan ordered Carmel flagstone from the nearby Pebble Beach quarry, redwood from the Big Sur Lumber Company and granite stone collected off the beach. Now, almost 100 years later, the majority of these buildings are still in use, with original materials intact.

According to Sood, “How she used daylight to light and warm space in the early 20th century was incredible. She designed houses with thickness in the walls to retain the thermal temperature,” she explains. “Today, we are talking about Julia Morgan and green design in the same breath.”

“She’s a big inspiration for me,” Sood adds. “She was determined, yet quiet, and with her business acumen she took on a huge diversity of projects. [Like her] I want to use the skill of design on any scale, from small to large projects. As a businesswoman in my own practice, I see her as a trailblazer.”

In the meantime, those who dwell or work in a Julia Morgan space are grateful to be surrounded by handiwork that has survived earthquakes, winds, bulldozers and the test of time.

In San Francisco, interior designer Kathleen Navarra occupies an office and retail space on Polk Street. It features an ornate wood balcony carved with grapes and vines on the second level, and even a trail of vines carved underneath the balcony. The door on the ground level is equally intricate. Navarra recalls, “Five years ago, we walked into this space not knowing the history of the building. However, there was a sense of inspired peace.”

Adding to the joy that this was a Morgan structure, Navarra learned that the first owner was Jules Suppo, one of Miss Morgan’s most trusted craftsmen, a woodcarver who created works for Hearst Castle. The architect created the combined workshop and apartment house just for his needs. Making this discovery made perfect sense to Navarra.

Over in the Berkeley hills, Trish and Tony Hawthorne have no intention of downsizing now that their children have moved out and started careers and families of their own. Their grandchildren are the next generation who visit and will hear stories of the “client’s architect.”

“I have a harmonious feeling living here,” says Hawthorne. “There is plenty of balance and light, and enough decoration in the patterns of the windows and tiles around the fireplaces. People who come here often say the house is soothing. I think she was amazingly good at what she did. It is such a pleasure to live in a work of art.”

- William Randolph Hearst with Julia Morgan during the construction of Hearst Castle. Photo: Irvin Willat, 1926 courtesy of Marc Wanamaker/Bison Archives

- Hearst Castle, Roman Pool, 1930-35, diving platform. Photo: Joel Puliatti from “Julia Morgan, Architect of Beauty” by Mark A. Wilson. Reprint permission by Gibbs M Smith.

- The Fairmont Hotel, San Francisco, c. 1910, shortly after Julia Morgan rebuilt it.

- A current view of the Fairmont’s lobby, as Julia Morgan rebuilt it. Photos: Courtesy of the Fairmont San Francisco.

- YWCA Building (Hollywood Studio Club), Hollywood, CA. Photo: Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections, California Polytechnic State University

- The Berkeley Woman’s City Club, [1928-29] entry hall. Photo: Joel Puliatti from “Julia Morgan, Architect of Beauty” by Mark A. Wilson. Reprint permission by Gibbs M Smith.

- Chapel of the Chimes, Oakland, gothic loggia. Photo: Joel Puliatti from “Julia Morgan, Architect of Beauty” by Mark A. Wilson. Reprint permission by Gibbs M Smith.

No Comments