01 Sep Perspective: Nicolai Fechin [1881-1955]

The winter of the year 1920 was one of the hardest in the history of the Russian Revolution. All at once everything seemed to reach its lowest ebb and people lived in an atmosphere of rapid deterioration. … The ardent citizens of the new, free Russia were now to be seen going about poorly clothed, half-frozen, hungry and very much depressed. The economic situation of the whole country had reached a very pitiful state. Added to this, an unusually cold winter overtook the already exhausted people and unmercifully tortured them by frost, darkness, and, above all, by hunger.

Caught between the fearful waves of loosened human passions and the unconcern of nature, we had to turn ourselves to nature and pray for mercy.

—From Alexandra Fechin’s memoir, March of the Past

At a desperate time in history, Nicolai Fechin taught at the Kazan Art School while his wife, Alexandra, and small daughter, Eya, eked out an existence in the Pine Grove of Vasilievo, some 20 miles away. Fechin commuted on the Kazan Moscow railroad on the weekends. Besides food, transportation and fuel shortages, paint and canvases, too, were difficult to obtain. He ground pigment, used tempera paint and even stretched jute potato sacks for canvas. In his autobiography, Fechin said of the school at that time, “ … the cold inside was unbearable …We drew and painted in fur coats, mittens and heavy felt boots. It was impossible to undress. … I felt deeply how swiftly and uselessly I was losing my creative energy. All art was used for propaganda.”

When Fechin found himself forced to paint bureaucratic commissions by the Soviet regimes of Marx, Lenin and others, the artist plotted his escape. But not before life grew even more bleak. His parents died of typhoid and Fechin himself developed pneumonia and could not teach.

Of the 1920 arrival of the American Relief Administration in Kazan, Fechin’s daughter, Eya, later said, “These foreigners were ‘saving’ our country.” Fechin echoed Eya’s admiration for America in his own autobiography: “There is peace and freedom in their country. One can work, paint whatever one likes. There is no tragedy, no hopeless chaos to tear their nerves apart — my roots are here but I am losing all initiative for work, my will for life and hope are gone.”

Despite upheaval of epic proportions, Fechin continued to create. How much of his bold, explosive style and tempestuous disposition were a result of what life flung at him we cannot know. What we do know from even a cursory glance at his remarkable life and unmatched body of work is that world wars, revolution, civil war, famine, collapse of an economy, illness, a forced emigration, language barriers and an eventual divorce could not crush Fechin’s drive to produce art. As the ground shifted dangerously beneath his feet, his art won awards and was collected and displayed worldwide.

Today, more than five decades after his death, Fechin’s work is earning record prices at auction. Mike Overby, partner in the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction, said that the market for Fechin’s work has held up better than most and even increased in the last couple of years due in large part to the Russian buyers who have been purchasing his work. At one auction, eight foreigners bid by telephone on a single Fechin painting. A Russian won the bid.

Nicolai Fechin was born in 1881 in Kazan, Russia, capital of the Tartar Republic on the Volga River. Fechin’s father, Alexandrovich Fechin, established a shop for carpentry, carving and gilding the beautiful screens and iconostases for churches in the cities and countryside. In his father’s shop, young Nicolai fell in love with woodcarving. At 4, Nicolai became deathly ill with “brain fever” (meningitis) and fell into a coma for two weeks; even the best doctors could do nothing and feared the child would be mentally impaired if he lived. His parents were told to pray for a miracle. As a last resort, the heavy iconostasis of Mother Mary, which took two men to carry, was brought from the church and passed over the boy. He showed immediate signs of life and eventually made a full, and quite miraculous, recovery.

Back in his workshop, Fechin’s father needed someone to draw the designs for the carvings he labored over. Alexandrovich Fechin loved art but could not draw. At 6 years old, Nicolai stepped in to do all of the drawings.

Fechin’s formal training began when he was 14 at the Kazan Art School, an extension of the Imperial Academy, which he attended for five years. He was accepted into the prestigious Imperial Academy of Petrograd (now Leningrad), which belonged to the Imperial Court and was often visited by the czar. Fechin completed eight years at the academy; his studies included architecture and anatomy, for which he produced 300 drawings in preparation for his first exam. Of his highly influential professor, Ilya Repin, Fechin said, “[He] valued everything more or less original in the student. … He not only saw the work of the artist, but his soul as well.” As a result of oppression from the war with Japan and the subsequent first revolution, Repin left the academy abruptly. In his autobiography, Fechin wrote, “We, the students, were actually left to our own resources and these last two years were the most essential to me as an artist. Now that we were left alone without supervision, it became necessary to be responsible for ourselves and we worked with more diligence than ever before. There was no one to praise or deride so I, for the first time, began to work experimentally, and the very first winter my technique changed radically.”

As evidence, Fechin’s final painting for the academy won the Prix de Rome award, after which he was invited to international exhibitions, including the Munich Glaspalast and Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute. At the latter, his work was noticed and collected by W.S. Stimmel and Jack R. Hunter, both of whom would be instrumental in aiding with Fechin’s emigration to the United States. National and international awards stacked up. From the beginning of his professional career, thanks to numerous awards and recognition, Fechin was in demand in galleries throughout the world. Collectors in Italy, Germany, France and the United States sought his art.

Fechin graduated from the academy with a scholarship to travel abroad to study art and paint. He wandered through the art capitals of Europe and absorbed the art of Austria, Germany, Italy and France until, he said, he was “dizzy.” He produced no art on the trip, but explored the color in light and air used by Renoir, Degas, Manet, Monet and Seurat, all of whom would have an impact on his work throughout life.

In 1913 the beautiful, aristocratic Alexandra Belkovich, daughter of the founder of the Kazan Art School, became Nicolai Fechin’s wife. Fechin called her Tinka, and in 1914, at the dawn of World War I, the couple had a baby girl named Eya. Fechin continued to teach at the Kazan Art School as the country deteriorated. During the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, Tinka and Eya fled to the family’s country home. In 1923, after securing assistance from every possible connection, the family left Russia for New York City where they were swept off the boat, taken to accommodations, and helped to get established. Fechin immediately resumed his painting and teaching. After three years, he developed tuberculosis and was advised by his doctor to seek a dry climate. Upon the recommendation of John Young-Hunter, a fellow artist, and the invitation from Mabel Dodge Luhan to use one of her guest houses, the family moved to the remote village of Taos, New Mexico.

By 1926, when the family arrived in Taos, Fechin was middle-aged. Surrounded primarily by Pueblo Indians and Spanish Americans, he was inspired to paint the dignity of nature and the people of the earth. His paintings gained in boldness and maturity and became even more vibrant; lighter, brighter values and brilliant, pure color. In a Russian article on Fechin, Galina Tuluzakova wrote, “The radical changes of the artist’s world outlook take place in Taos, New Mexico. In paintings it was expressed by joyful, bright, hot colors of maximum intensity.”

In Taos, the Fechins bought a home which he remodeled and expanded. Nicolai painted while the daylight was good and then the woodcarving of his childhood flooded back as he hand-carved beautiful details into every room, building and carving furniture throughout the home. Today, the Fechin House is the Taos Art Museum, where visitors can leisurely wander the rooms, admiring Fechin’s work, from the hand-carved wood to the wild, seemingly random strokes of his brush and palette knife on the canvas of his portraits.

As his buffer from the outside world, Tinka communicated for Nicolai and conducted much of his business. She kept visitors at bay while he painted, as Nicolai could not tolerate interruptions. Because she often took the brunt of his angst, the Fechins’ marriage was thought to be full of strife.

Art students spoke of Fechin’s normally quiet demeanor and sudden outbursts when he didn’t approve of his or her painting. He would reportedly strike a loaded paintbrush across the canvas, shouting “No!”

After an angry outburst directed toward Tinka in front of patrons, his wife asked for a divorce. She said she could have forgiven him had the visitors not witnessed it.

In 1934, the Fechins’ tumultuous marriage ended. Severed from his homeland and now the woman he loved, Nicolai and Eya returned to New York for a disastrous year, ill-equipped to function without Tinka running the household.

Shortly thereafter, Earl Stendahl, an art dealer in Los Angeles, extended an invitation to Fechin to teach at his gallery. Fechin accepted, moving to Palm Springs, then Hollywood, finally settling in a canyon near Santa Monica where he lived out his days. During that time he traveled with students to paint in Mexico and Bali in the South Seas. According to Erion Simpson, Director of the Taos Art Museum’s Fechin House, Fechin still used his favorite palette during this period, but lighter tones evolved in his work.

In contrast to the Impressionists, known for their short brush strokes which create surface tension with a soft, feminine look, Fechin used bold, wide brush stokes, creating emotional tension with a masculine result. For years, both when he was alive and long after his death, scores of artists have paid tribute tried to Fechin by emulating his fresh, bright, strong style, so much of which was a result of his life and times, his arduous education, years of teaching, and Fechin’s raw genius.

Because personal passions for Fechin’s work trumped even prickly Soviet-American politics, an almost legendary international exchange exhibition was accomplished at the height of the Cold War. In 1976, Forrest Fenn of the Fenn Gallery in Santa Fe made arrangements through the Soviet Minister of Culture for a remarkable cultural exchange: 36 of Fechin’s Russian paintings came to the United States for an impressive retrospective. Nearly 2,000 visitors attended. The next year, 36 American Fechins were sent to exhibit in the Soviet Union. Over the course of his life, Fechin had become a man with two countries. “One comfort is that fate has divided my life between two great people,” he later wrote.

Russia did not forget her son. After his death in 1955, Eya returned her father’s ashes to Kazan where the Kazan Art School is now the Fechin Art School. The city is also home to the largest display of Fechins in Russia, at the Kazan Art Museum.

And so across the ocean, the years and the political landscape, we share in the pride and celebrate the art of Russia’s native son, Nicolai Fechin. Summing up his place in the art world, Overby cuts to the chase: “Fechin is definitely one of the most important artists we sell because he’s not pigeonholed as just a Western American artist. He transcends that and is as popular in Russia and internationally as he is here in the States. His ability to say a lot with very few brush strokes sets him apart from the other artists of his day.”

From the author: Many thanks to Forrest Fenn for allowing access to his Fechin archive including letters, diary, photographs, articles and recorded interviews.

Carleen Milburn documents the landscape, art and people of the West for national and regional publications. She lives with her husband on a small ranch in Montana’s Missouri River Valley.

- The Fechin home in need of repair before it was beautifully restored by Taos Pueblo Indian Joe Martinez. Photo courtesy of Forrest Fenn Archives

- Carving wood was Fechin’s passion from early childhood as seen in detail throughout his home which is now the Taos Art Museum and Fechin House in Taos. Note the color added.

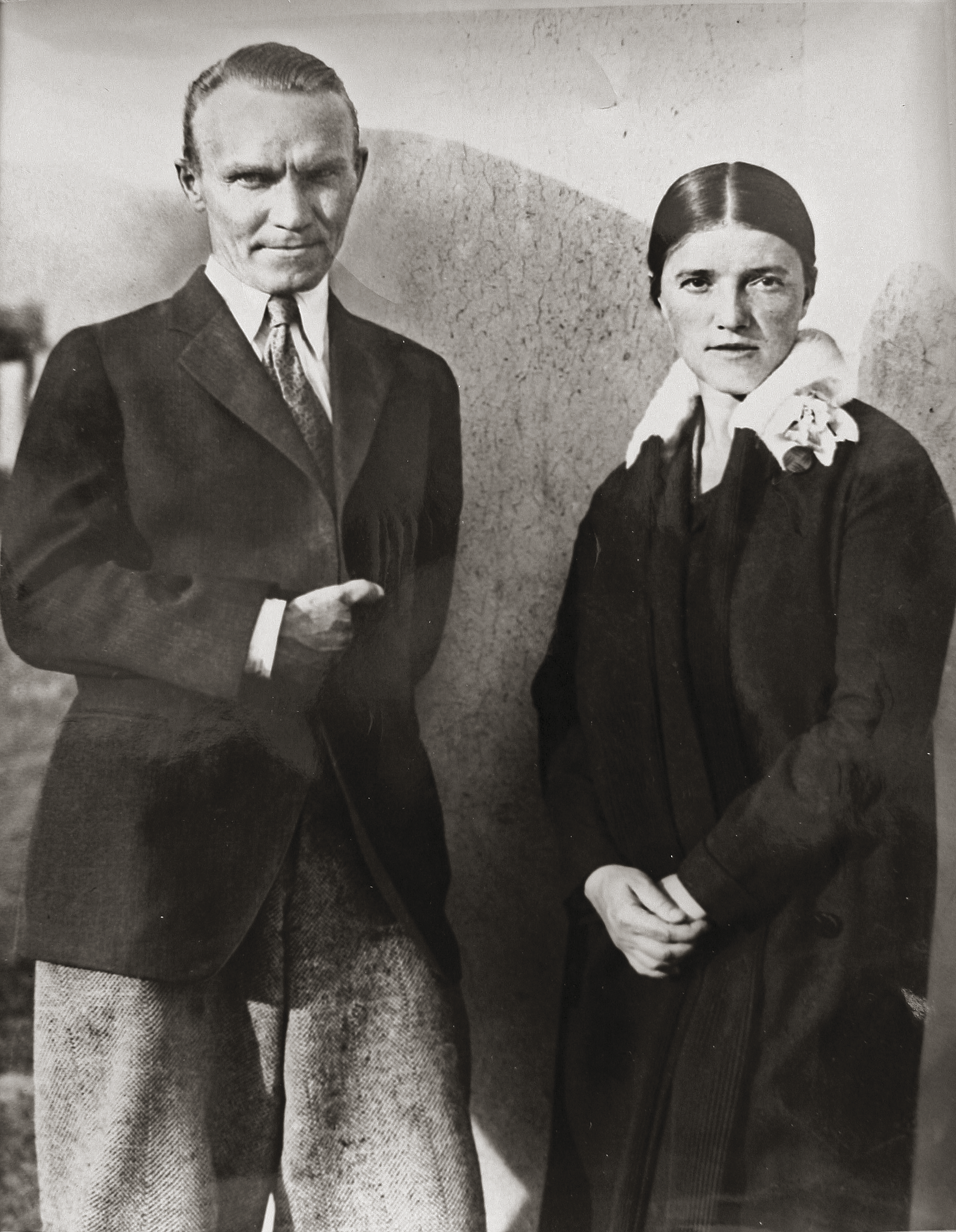

- Nicolai Fechin and wife Alexandra during their early years in Taos, ca. 1928. Photo courtesy of Forrest Fenn Archive

- Light filters in from unusual windows illuminating hand-carved wooden details on furniture and construction elements such as posts, rails, mantels, doors, and window trim. Photos: Mike Milburn

- Nicolai Fechin, “Lillies and Shell” Oil | 24 x 20 inches | Forrest and Peggy Fenn collection. Photo: Mike Milburn

- Nicolai Fechin, “Alexandra on Volga” | Oil | 1912, 23.5 x 28.75 inches | Taos Art Museum and Fechin House collection. Photo: Amy Archer

- Nicolai Fechin, “Self Portrait” | Oil | 10 x 10 inches (year unknown) | Photo: Amy Archer

- Nicolai Fechin, “Eya in Peasant Blouse” | Oil | 1933 | 24 x 26.5 inches | Taos Art Museum and Fechin House collection. Photo: Amy Archer

No Comments