19 Jul Perspective: Paul Kane [1810–1871]

He was a rugged expeditionary, a man who in 1845 trekked alone through much of the Canadian outback and traveled with Hudson’s Bay traders through the Northwest Territories from 1846 through 1848. Yet he was a perceptive artist who made hundreds of sketches on those trips and once home, adapted them into stunning, colorful oils. He was a boy in Toronto when that city was a rural outpost called York, yet he became a connoisseur of European art who turned his studies of chiefs into portraits evoking Rembrandt’s or Velasquéz’s. He was a realist who transformed his observations of Native life into romantic narratives for both aesthetic and monetary gain. He was the Irish-born Paul Kane, recognized in his time as the patriarch of Canadian painting, yet remaining one of its more controversial practitioners.

The controversy is summed up by Kenneth Lister, retired assistant curator of anthropology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM): “If we look at a Paul Kane sketch and we look at a Paul Kane oil painting, can we assume that what we’re looking at in the latter is what he actually saw?”

It’s the old debate between realistic and romanticized depictions, one that raged in the 19th century about the work of painters such as George Catlin and Albert Bierstadt. ROM owns the largest collection of Kane sketches and paintings, the befores and afters of which now can be compared. As the author of Paul Kane, The Artist: Wilderness to Studio, Lister is an expert on Kane’s art — and an anthropologist, archaeologist and explorer who has searched by kayak and car for the painter’s 19th-century sketching sites.

“It is amazing to sit or stand on the rock that Kane sat on to make this particular sketch,” he says. Lister’s passion is characteristic of that felt by many Kane aficionados, for the artist lived a fearlessly intrepid life.

Born in Ireland in 1810, Kane immigrated as a boy to Toronto where his father, a former Royal Horse artilleryman, sold liquor. Kane’s talent surfaced first in portraiture, then in sign and furniture painting. Though entranced by the indigenous people living around York, he soon left Canada, spending five years touring America’s Midwest as an itinerant portrait painter, eventually voyaging down the Mississippi River to New Orleans.

In 1841, he booked passage to Europe and spent the next two years visiting museums in Genoa, Florence, Venice and Rome, copying the work of masters. He hiked south, from Rome to Naples, then trekked north through the Great Saint Bernard Pass to Switzerland, traveling to Paris and eventually to London. There he heard the American artist George Catlin lecture, a circumstance that would lend direction to his life.

Catlin, between 1830 and 1836, had made five trips to the western U.S. In 1842, he was lecturing on Native American life and exhibiting his Indian Gallery paintings in London. Kane attended and “may have met Catlin,” says Lister. He was enormously impressed with the painter’s directive to “salvage” indigenous culture from European civilization, and with the sheer adventurousness of his treks.

Canada’s northwest was largely unexplored; it was a deep wilderness. Kane would return to the States and spend the next two years acquiring funds for an expedition there. His goal was to field-sketch indigenous life and culture for ethnographic purposes, but also to make studies for future oil paintings. The “noble savage” concept was in vogue, its main idea being that “primitives” lived in prelapsarian bliss and that their lifestyle should be emulated. This was a Romantic notion, and as ROM’s Arlene Gehmacher writes in her monograph, Paul Kane: Life & Work, “In embracing his own ‘savage’ project, Kane was very much in line with the Victorian imperialist belief that North American aboriginal peoples were all but certain to vanish, threatened by settler contact and encroachment.”

In June of 1845, Kane set out, trekking and boating west above the Great Lakes, sketching in Saugeen territory, before being convinced by a Hudson’s Bay officer of the folly of continuing alone.

In November, Kane returned to Toronto, planning both to acquire permission from Hudson’s Bay to explore its territory and to have its assistance. “This was before Canada became a nation,” Lister says. “The Hudson’s Bay Company essentially owned the Northwest.”

“Beginning in late May 1846, [Kane] traveled by canoe, York boat, horse and on foot across prairies, the subarctic and mountains, with fur-trade brigades or with hired local guides,” Gehmacher writes. He sketched under the most hostile of circumstances. For more than two years, he followed Hudson’s Bay routes, “venturing as far north as Fort Assiniboine and as far south as Fort Vancouver in the Oregon Territory, exploring that vicinity and northward on Vancouver Island.”

He made life-studies of Cree, Métis, Chinook, Ojibwa, Blackfoot and other First Peoples — sketches that, upon returning to Toronto, he spent seven years transforming into oils. “The sketches were his ticket into the studio,” Lister says. “He knew exactly what he was doing.”

Kane wrote in his memoir, Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America, that his goal had been “to sketch pictures of the principal chiefs and their original costumes, to illustrate their manners and customs, and to represent the scenery of an almost unknown country.” He would take liberties with the accuracy of these paintings, however.

Flat Head Woman and Child is a case in point. The painting purportedly shows a Cowlitz woman with a slanted forehead (fashionable in this tribe), holding an infant which lies upon a flattening board. “It was with some difficulty,” Kane wrote, “that I persuaded her to sit, as she seemed apprehensive that it would be injurious to her.” In fact, the oil was rendered from two watercolor sketches, one depicting a Songhees woman and the other a Cowlitz baby. This conflation infuriates ethnographers and appears to negate Kane’s own pledges to accuracy.

Another example of Kane’s artistic license is found in an oil depicting Mount St. Helens erupting on a night during Kane’s visit. “I had a fine view of Mount St. Helens throwing up a long column of dark smoke,” Kane wrote. However, the volcano had erupted several years previously. Other oils, Assiniboine Hunting Buffalo and The Man That Always Rides, shows Assiniboine and Blackfoot warriors on improbable white Arabians — a trope favored by European painters, from Eugène Delacroix to Théodore Géricault.

“Kane would not have seen his use of aesthetic conventions as contradicting his pursuit of accuracy,” writes Gehmacher. “For Kane, truth was not necessarily objective verisimilitude but the transcendence of the particular in order to evoke a more profound essence of his subject.”

In other words, he was working as an artist. The studio oils reflect this commitment. He’d assess what a sketch depicted, then trust his subconscious to reshape it. As Gehmacher notes, “Many of the oils embody conventions of Romantic painting: the tableau-like, staged compositions; the dramatic, moody skies; the diffuse, murky tonalities; the spectacular light effects … the sublime or picturesque views; and the idealization of the individuals who were his subjects.”

Such idealization is most apparent in his portraits created after his expeditions. Kane’s portrait of the half-Cree, half-British woman, Cunnawa-bum, shows a Métis girl of striking beauty holding a swan’s wing fan in what Kane described as “a most coquettish manner.” Cunnawa-bum’s European features permit Kane to idealize them for his Canadian viewers, and as Gehmacher writes, she “becomes a sort of cover girl for Kane’s life project.”

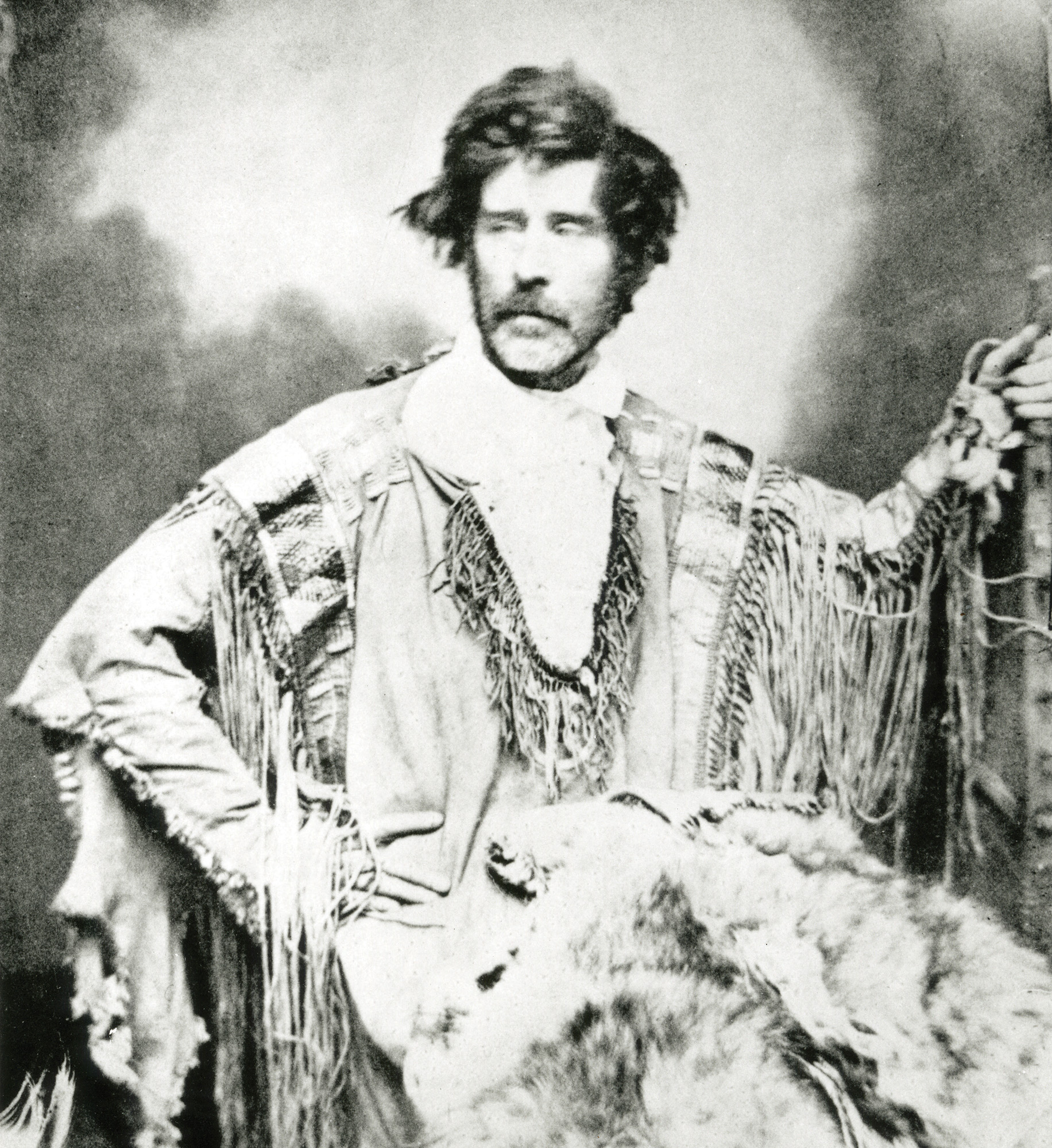

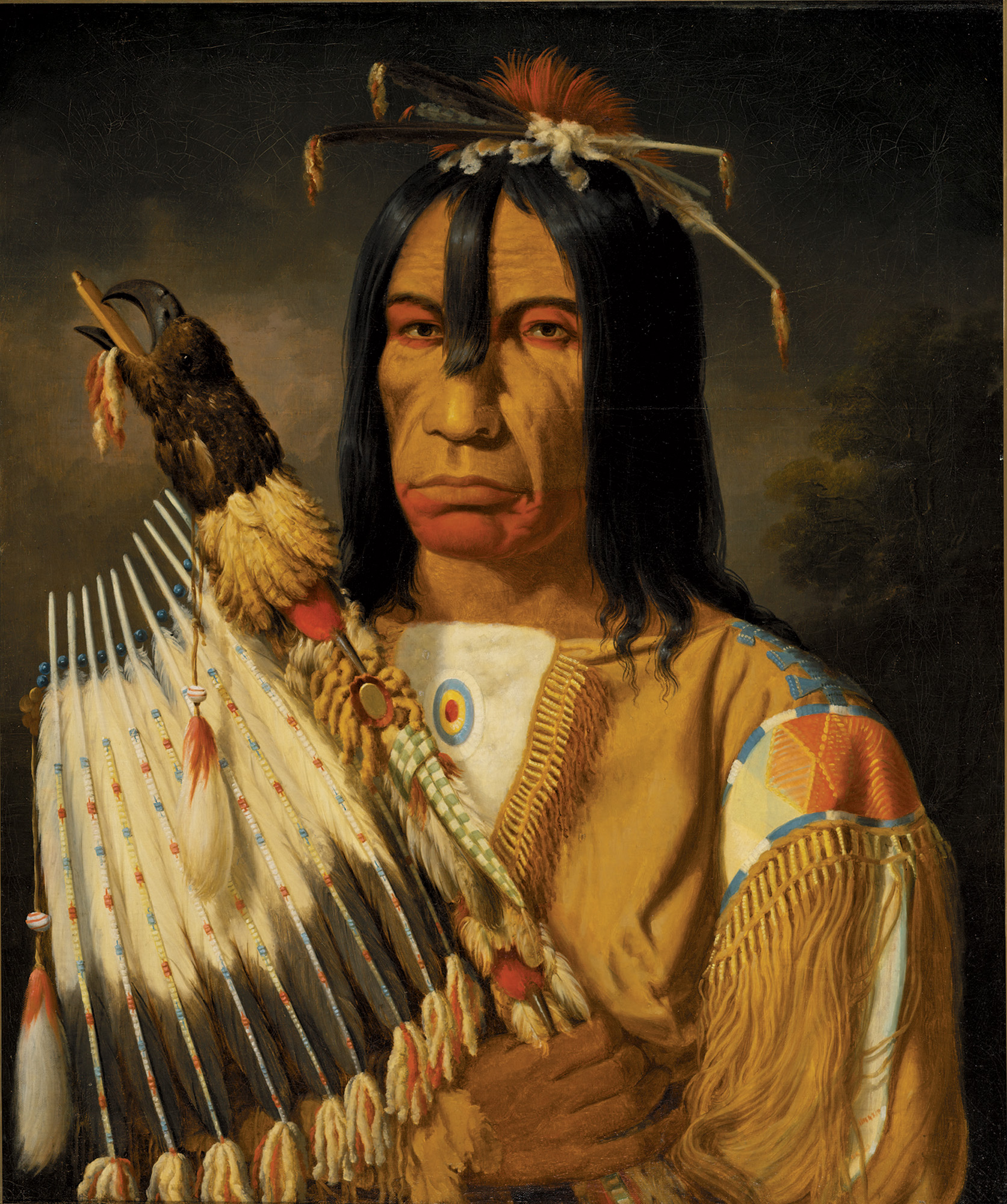

In his portrait of Cree chief, Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, The Man that Gives the War Whoop, the half-nude subject in Kane’s watercolor sketch bristles with gravitas, while in the later oil Kane anglicizes his physiognomy and warms him in colorful buckskins. Even Kane’s photographic portrait of himself, hair tousled and chest clad in a fringed and beaded shirt, suggests the European gone Native.

Idealization was marketable, and picturesque renditions of First Peoples and their landscapes sold. In 1851, Kane’s patron, George W. Allan, paid him $20,000 for 100 paintings that took him five years to complete in his Toronto studio. These oils would constitute the bulk of Kane’s output. Even then he was a celebrated a painter, but it was his role as an ethnographer which distinguishes him. As Gehmacher writes, “It is the subject matter of his work that has guaranteed his place in Canada’s art history.”

The adventurer spent the remainder of his life quietly in Toronto, but what he saw and experienced during his years of exploration may have haunted him. He’s described by Allan’s daughter, Maude Cassels, as having been “melancholy” and “disgruntled and despondent.” Though wealthy, his eyesight was failing, he’d taken a bad fall and 90 percent of his work was in a private collection, unavailable for public view. On February 20, 1871 he died of “a liver complaint,” a euphemism for undiagnosed maladies — in his case, possibly syphilis contracted among the voyageurs, or alcoholism.

His stature as the father of Canadian art is not disputed. “As a studio painter Kane was an artist first and an ethnographer second,” Lister writes. “He made grand on canvas what he recorded accurately in his field sketches. … No other artist in Canada’s history has provided us with both the wilderness notes and the studio record to the degree that Kane has. No other artist has granted us a detailed ethnographic and environmental record of a moment in Canada’s past, and then using that record, developed a series of paintings that invites us to understand the nature of the artist’s response to the philosophical character of the country.”

The resurrection of his reputation began in 1971 with the publication of Kane’s memoir, edited by J. Russell Harper, Paul Kane’s Frontier. The book marked the centenary of Kane’s death and was followed by several shows of his work.

In 2002, his 1845 painting, Scene in the Northwest: Portrait of John Henry Lefroy, sold at Sotheby’s Toronto for more than $5 million and is timeless. It depicts a beautifully dressed gentleman in the snowy outback, flanked by sled dogs, an aide and a Native woman. Though in their company, Lefroy — like Kane in the wilderness — stands alone.

- Paul Kane. c. 1850. Photographer unknown. Visual Resources Collection, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives

- “Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, Plains Cree” | Oil on Canvas | 75.9 x 63.4 cm | 1849–1856 | With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

- “The Man That Always Rides, Blackfoot” | Oil on Canvas | 46.3 x 60.9 cm | 1849–1856 With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

- “The Constant Sky, Saulteaux” | Oil on Canvas | 63.5 x 76.2 cm | 1849–1856 | With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

- “Scene in the Northwest: Portrait of John Henry Lefroy” | Oil on Canvas | 55.5 x 76 cm | 1845–1846 | The Thompson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario

- “Cunnawa-bum, Métis” | Oil on Canvas | 64.2 x 51.5 cm | 1849–1856 | With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

No Comments